By Eric Vandenbroeck and

co-workers

Reassessing the First War part one

Where some months ago we postulated that

while for some, the

Munich Agreement signaled the beginning of the Second World War,

challenging this standard road to war, however, one has to go back

to the contentious issue of

war guilt, which became divisive and passionately debated as soon as the war had broken out, it

was the "stab in the back" (that Germany didn't lose the

First World War) myth hence the Germans who had signed the Armistice

on 11 November 1918 were stipulated as "November criminals." Most historians

agree the stab-in-the-back legend contributed to the rise of

National Socialism. To this one can add that this

belief led to Hitler's push for rearmament and the revision of Germany's borders parallel

with theManchurian Incident, a

situation aggravated by the empire's invasion of China in 1937 and then brought

to a breaking point in 1941 when Ribbentrop, told Japanese ambassador

Hiroshi Oshima, Germany, of course, would join the war immediately. There

is absolutely no possibility of Germany’s entering into a separate peace with

the United States under such circumstances. The Führer is determined on that

point. The Japanese did not tell the Germans that the Combined Fleet had already been put to sea.

Whereby Berlin had, in effect, issued Tokyo with a blank check, which it

could cash at a moment of its own choosing.

As for the First World War we also have seen,

that from the outset, there was a failure to realize that the murder of the

heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire by a young terrorist might be

the trigger of a great European war. In fact even after Austria-Hungary went to

war with Serbia on 28 July 1914, while some observers feared that the conflict

might escalate while many also hoped that the situation could and would be

localized.

There furthermore is

something profoundly unsettling in the statistic that after China declared war

on Germany in August 1917, more than 1.4 billion people (out of a total world

population of 1.8 billion) were formally at war with each other. Perhaps an even

more unsettling realization is that during 1917 and 1918, most neutral

countries also experienced a profound unraveling of social norms, political

order, and economic stability.1

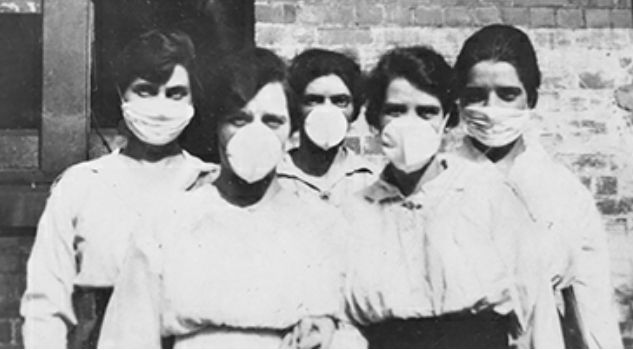

Civil wars, social

unrest, in some places complete social and political disintegration, alongside

anarchy, hunger, starvation, inflation, a profound sense of grief, and a global

influenza pandemic, ensured that their lives and livelihoods remained unsettled

well after November 1918.2

Despite the commonly

used identifier – the ‘Spanish flu’ –, it was quite clear to contemporaries that

the pandemic did not originate in Spain.3 The influenza only became a subject

of global public discussion, however, after it hit Spain in the European summer

of 1918. As a neutral country, Spain did not have the same censorship rules in

place regarding public health as the belligerents. And like all war-related

news at the time, news from neutral countries spread particularly fast. Still,

by the time Spain was infected with the virus and reporting it, the pandemic

had already raised alarm bells in the United States, France, Britain, and

Germany. None of these belligerent governments were initially willing to take

any serious measures to contain its spread because the war was still on and

their military priorities came first.4 As a result, the flu became part of the

fabric of total war.

Across Europe, for

instance, many experienced the disease as treacherous: as an invisible enemy

attacking their war-weakened society from within,

Others suspected that

their enemies had released the virus as an alarmingly effective new weapon of

mass destruction. Many of them distrusted their own governments’ roles in the

flu’s management, not least as they also understood that fighting ‘the war’ remained

a primary priority (as opposed to combating the flu). In France, rumors

abounded that the medical catastrophe facing them could not be caused by

something as ‘innocent’ as a flu bug and that the authorities were actually

trying to keep the secret that deadly cholera had returned.5

After Austria-Hungary

went to war with Serbia on 28 July 1914, most observers feared that the

conflict might escalate and expand across the European continent. Yet many of

them also hoped that the situation could and would be localized like so many

European inter-state wars of the past. As a result, governments within and

outside Europe dutifully declared their formal neutrality.

Then, the years 1853

to 1856 marked a fundamental shift in how wars were conducted between the

Anglo-European states. From the outset of the Crimean conflict, the

belligerents ended the practice of privateering, which had been the mainstay of

economic warfare in Europe and between the European empires during the early

modern period. They sustained the right of neutrals to trade unhindered in

non-contraband goods. They also imposed strict rules regarding the legitimate

conduct of economic warfare: for example, blockades could only be imposed if

they were effective. These ideas were sanctified in international law with the

signing of the Declaration of Paris in 1856.6

The agreement for inter-state war only as a

defensive measure

The 1856 Declaration

of Paris was the first of several attempts to create a universally recognized

international law of war. The 1863 Geneva Convention, signed initially by

twelve European governments, established that medical units would disperse aid

to all who needed it in time of war. These Red Cross units effectively

functioned as a ‘neutral’ humanitarian force that operated on (or near) the

battlefield. The 1868 St Petersburg Declaration, initially signed by seventeen

governments, agreed that some weapons were too horrific for use in ‘civilized

warfare’ (by which they meant wars conducted between recognized states).7

Fifteen governments met in Brussels in 1874 to define a ‘law of war.’ Their

deliberations would become the basis on which the Hague Conventions of 1899 and

1907 were built. While the Hague conventions represented established wartime

practices of most European countries up to that point in time, they were

revolutionary. They projected those expectations outwards to cover the world:

China, Japan, the United States, Persia, and Siam signed the 1899 agreements.

They also focussed heavily on the rights

and obligations of neutral states, entrenching the idea that neutrality was a

protected status in times of inter-state war. Forty-four governments were party

to the 1907 Hague Conventions, including many Latin American states,

globalizing the application of international law in the process.

For an inter-state

war to be considered legitimate, it only had to be conducted as a defensive

measure.8 Increasingly, aggressive warfare between states was deemed

unnecessary, dangerous, and against the precepts of ‘civilized’ behavior. Yet,

despite such rhetoric, martial virtue played an equally prominent role in

Anglo-European political cultures, often defining, racializing, and gendering

concepts of citizenship and duty to the community, nation, and empire.9

Within the numerous

empires that stretched across the world by the early 1900s, however, state

violence was an everyday part of life, in terms of both police actions (to

repress political unrest, economic strikes, and colonial resistance) and the

means to acquire new territory, markets, and human and material resources. This

kind of imperial warfare was seldom considered by its agents in the same way as

inter-state military violence. It was generally brutal and rarely restrained.

However, this did not mean that the violence was left unseen or did not evoke

considered discourses about its legitimacy. The violence was all too real for

its victims and proffered a powerful reason why ongoing military resistance

against the empire and its agents was warranted. For its agents – the soldiers

of the empire – their actions were both legitimated as essential (for the

survival of the empire) and celebrated as courageous (not least because they

were conducted against supposed ‘savage’ and ‘barbarian’ peoples who did not fight

fair, unlike the supposed ‘civilized’ men who undertook the violence).10

Somewhat

paradoxically, then, Anglo-Europeans in the nineteenth century were both ardent

proponents of regulating inter-state warfare and limiting its spread in the

name of ‘civilizing’ and humanitarian forces and agents of extreme state

violence in the name of advancing ‘civilization’ and imperial glory. Like

Belgium, even permanently neutral states could acquire an empire using warfare

and rule their imperial subjects with an iron fist. Of course, the paradox only

exists if you ignore the racial categorizations that operated in

nineteenth-century Anglo-European societies. By 1900, not only were many

non-European communities subjugated into one of the Anglo-European empires

(including the United States), but they all had to operate in an international

diplomatic, economic and cultural system that forced Anglo-European and

capitalist values onto the rest.11 In other words, in the global system that

dominated the nineteenth-century world, wars between ‘civilized’ states and

people were considered according to different standards than wars conducted by

‘white’ against ‘non-white people or those fought between or within supposedly

‘non-civilized communities.

The Russo-Japanese

War (1904–5) offers a useful example of these competing visions of war, not

least because it was an intensely documented media event.12 In the global

press, the war was overwhelmingly recognized as an inter-state war, pitting the

Meiji empire against its Romanov counterpart. As such, newspaper reports

focused mainly on military conduct and the diplomacy surrounding the war. In

conducting their military campaigns, the Japanese government was cautious about

upholding the international law of war.13 Japan needed to be seen as operating

within the constricts of ‘legitimate’ warfare to confirm its status as

‘civilized’ and equal in the international system. As a result, international

lawyers accompanied Japan’s armies in the field, and Russian prisoners of war

were offered all due care as specified by the 1899 Hague Conventions.14 In the

international press, the war was also assessed in terms of the requirements of

‘legitimate’ warfare and the prescriptions of international law. This was particularly

important because Russia attempted to interfere in Japan’s trade with the great

neutral powers. A considerable body of academic work appeared on the

international law of war and neutrality in relation to the conflict, much of

which also received commentary in the global press.15

In keeping with the

inter-state war depiction, many editorials also considered the Russo-Japanese

War a heroic struggle of competing for industrial empires, a war in which the

Japanese ‘tiger’ defeated the Russian ‘bear.’16 In Japan, the war offered a means

to advance nationalism and the idealization of soldiers as archetypal

citizens.17 The costs of warfare were also amply illustrated. Russia’s military

defeat inspired anti-Tsarist revolutions across the Romanov lands, highlighting

the unpredictable domestic impact of war on the volatile subjects of this

sprawling empire.18 The socialist revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg described these

anti-Romanov protests as reflective of the interconnected nature of global

warfare. The destiny of Europe, she suggested in 1904:

It isn’t decided

between the four walls of the European concert, but outside it, in the gigantic

maelstrom of world and colonial politics. This war brings the gaze of the

international proletariat back to the great political and economic

connectedness of the world.19

For Koreans and the

inhabitants of Manchuria (which in 1931 then

was fully taken by Japan), of course, the Russo-Japanese War was one of

conquest, confirming Japan’s rising imperial power and de facto control of the Choson kingdom.

Quite in contrast to

the Russo-Japanese War, the global press presented the maelstrom of violence

that typified the Balkan Wars in 1912 and 1913 as a ‘people’s war.’ The neutral

media fixated on the national stakes involved in the conflict, pitting the various

Balkan communities (both ethnically and religiously defined) against the

Ottoman empire first and then against each other. War reports fixated on its

human cost: its ‘outrages,’ massacres, pillaging, and many refugees.20 In the

Balkan Wars, international law seemed not to apply because people, rather than

states, were the driving force behind the war.21

After July 1914,

warfare became an increasingly universal reality (albeit a distinctly different

reality depending on who you were and where you lived). Nevertheless, between

1914 and 1918, more and more parts of the world were formally at war. Even if they

remained formally neutral and removed from a military front, the socio-economic

consequences of conducting this multifaceted global war had a decisive impact

on most societies. If anything, the 1914-18 conflict globalized and normalized

warfare and extreme violence for its agents, victims, and observers alike. It

also removed many distinctions that contemporaries in the nineteenth century

made between inter-state warfare and other forms of state and non-state

military violence.

In 1914, it was

generally acknowledged that a country could remain neutral as long as its

government maintained a good relationship with the belligerents. That is to

say, neutrality was sustainable as long as the country was not invaded (when it

automatically became a belligerent) and as long as any violation of the legal

and political requirements of neutral states in time of war was policed by the

neutral government and was validated by the belligerents. According to these

legal rights and duties, neutrality maintenance was a complicated and involved

business. Regardless of how far away a military front was, neutral governments

had to be seen to mobilize troops and naval ships to patrol territorial

borders. They had to design domestic laws to prevent neutral subjects from

signing up to serve in a belligerent armed force or to keep them from smuggling

contraband to a hostile. Above all, neutrality maintenance involved constant

vigilance and diplomatic negotiation with belligerents. Any violation could lead

to a charge of ‘unneutral behavior’ and a corresponding declaration of war on

that neutral.

Successful neutrality

maintenance was also a matter of domestic politics. While in terms of

international law, a private subject of a neutral state could not endanger that

country’s formal position of neutrality, in practice, how neutral communities

behaved in relationship to a war mattered both to the political stability of

the neutral country and to their government’s relationship with the

belligerents. Neutral subjects internalized these responsibilities in varying

ways. They often mobilized their identity as neutrals to proffer humanitarian

support in the war or engage in ‘good offices’ or mediation attempts. They

usually advocated for the international good of their neutrality in keeping the

war from expanding. None of these positions prevented individuals from neutral

countries from sharing their opinions and perspectives on the war, including in

their news media. The Carnegie Endowment report on the Balkan Wars, described

above, is an apt example. Its report on the ‘rights’ and ‘wrongs’ of the war was

made from the self-proclaimed position of a neutral organization manned by

international lawyers from neutral countries, who professed they could

adjudicate the war because of their ‘impartial’ standpoint and their mutual

respect for the universal values of peace and justice embedded in international

law. From all these perspectives, neutrals considered themselves the

peace-keepers of the world.

Through the course of

the First World War, this peace-making role came under such intense strain that

by late 1917, many contemporaries argued that neutrality’s peace-keeping

function had not only come to an end but that entirely new world order was needed.

But what that new world order might look like and how it might impact one’s own

life were openly contested. For unraveling the many foundations of the

nineteenth-century world order, neutrality included the 1914-18 war years

inspired a wide array of alternative political narratives.

Perhaps

unsurprisingly, Germany’s invasion of Belgium that contemporaries returned to

as familiar iconography to explain the war as it evolved.22 It was also this

invasion that determined the rights and wrongs of the whole war in many

neutrals’ eyes. They did so even though equally awful acts of military violence

existed in the war between the Serbs and

Austro-Hungarians and would soon be occurring in military theatres across

eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Africa.23

1. Stefan Rinke,

Latin America and the First World War (Global and International History),

2017, pp. 256-7.

2. Alexander

Watson, Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I, 2017, p.

505.

3. Mark Osborne

Humphries, ‘Paths of Infection: The First World War and the Origins of the 1918

Vol. One, Influenza Pandemic, 2013, pp. 55-81.

4. Anne

Rasmussen Edited by Jay Winter, the Spanish Flu, 2013, pp. 337-8.

5. Rasmussen,

‘Spanish Flu’ pp. 339-43.

6. For more:

Jan Lemnitzer, Power, Law and the End of Privateering Palgrave MacMillan, 2014.

7. For more: Emily

Crawford, ‘The Enduring Legacy of the St Petersburg Declaration: Distinction,

Military Necessity and the Prohibition of Causing Unnecessary Suffering and

Superfluous Injury in IHL’ Journal of the History of International Law 20, 4,

2019, pp. 544-66.

8. William Mulligan,

‘Justifying International Action: International Law, The Hague and Diplomacy’

in Maartje Abbenhuis, Christopher Barber, Annalise

Higgins, eds, War, Peace and International Order: The Legacies of the Hague

Conferences of 1899 and 1907 Routledge, 2017, pp. 12-30; Daniel Segesser, ‘“Unlawful Warfare Is Uncivilized”: The

International Debate on the Punishment of War Crimes, 1872-1918’ European

Review of History 14, 2, 2007, pp. 215-34.

9. Cf James Sheehan,

Where Have All the Soldiers Gone? Houghton Mifflin, 2008, p. 41; Michael Paris,

Warrior Nation: Images of War in British Popular Culture, 1850-2000 Reaktion, 2000.

10. Martin Van Bruinessen, ‘A Kurdish Warlord on the Turkish-Persian

Frontier in the Early Twentieth Century: Isma’il Aqa Simko’ in Touraj Atabaki, ed., Iran and the

First World War: Battleground of the Great Powers I.B. Tauris, 2006, pp. 69-93.

11. For more: Marilyn

Lake, Henry Reynolds, Drawing the Global Color Line: White Man’s Countries and

the International Challenge of Racial Equality Cambridge University Press,

2012.

12. Marco

Gerbig-Fabel, ‘Photographic Artefacts of War 1904-1905: The Russo-Japanese War

as Transnational Media Event’ European Review of History 15, 6, 2008, pp.

629-42. With thanks to Steven Sheldon, Hemi David and Leon Ostick

for sharing their research on this subject.

13. Douglas

Howland, ‘Sovereignty and the Laws of War: International Consequences of

Japan’s 1905 Victory over Russia’ Law and History Review 29, 1, 2011, pp.

53-97.

14. Japan Times 5

July 1904, p. 3.

15. Howland,

‘Sovereignty’; Abbenhuis, Age pp. 209-10.

16. Chris Williams,

‘The Shadow in the East: Representations of the Russo-Japanese War in Newspaper

Cartoons’ Media History 23, 3-4, 2017, pp. 312-29.

17. Cf Simon

Partner, ‘Peasants into Citizens? The Meiji Village in the Russo-Japanese War’ Monumenta Nipponica 62, 2, 2007,

pp. 178-206; Rotem Kowner, ‘Becoming an Honorary

Civilized Nation: Remaking Japan’s Military Image during the Russo-Japanese

War, 1904-1905’ Historian 64, 1, 2001, pp. 19-38.

18. David

Crowley, ‘Seeing Japan, Imagining Poland: Polish Art and the Russo-Japanese

War’ Russian Review 67, 1, January 2008, pp. 50-69, esp. pp. 53-5.

19. Rosa Luxemburg,

‘In the Storm’ 1904, quoted in Crowley, ‘Seeing Japan’ p. 55.

20. H.F. Baldwin, A

War Phograper in Trace, Unwin, 1913.

21. Kramer, Dynamic,

135-7.

22. Cf Daniel Segesser, ‘Dissolve or Punish? The International Debate

among Jurists and Publicists on the Consequences of the Armenian Genocide for

the Ottoman Empire, 1915–1923’ Journal of Genocide Research 10, 1, 2008, p. 99.

23. As an example:

Alexander Watson, ‘Unheard-of Brutality: Russian Atrocities against Civilians

in East Prussia, 1914-1915’ Journal of Modern History 86, 4, 2014, pp. 780-825.

For updates click homepage here