By Eric Vandenbroeck and

co-workers

Reassessing

the First War part two

In 1914, as seen in

part one, it was generally acknowledged

that a country could remain neutral as long as its government maintained a good

relationship with the belligerents. That is to say, neutrality was sustainable

as long as the country was not invaded (when it automatically became a

belligerent) and as long as any violation of the legal and political

requirements of neutral states in time of war was policed by the neutral

government and was validated by the belligerents.

None of the

governments that went to war in July and early August 1914 were eager to engage

in a drawn-out conflagration. None of them had planned for such a scenario. No

strategic plans even existed for warfare between the imperial rivals in Africa,

for example.1 Instead, they pinned their short-war ambitions to a small number

of decisive military victories in Europe. Ideally, the continental war would

last a matter of weeks, at most a few months.2

Yet, the First World

War had profound global importance. It led to the collapse of four of the

world’s most powerful empires, namely Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, and the

Ottomans. It almost bankrupted the French and British empires. It occasioned the

Russian revolutions of 1917 and brought the Soviet Union into being. It

confirmed that the United States and Japan had become powerful industrial and

imperial states.

The war was carried

on the winds of global commerce, finance, and information exchange and was won

by those who most effectively mobilized the available human and material

resources. As a result, neutral and belligerent civilians were both victims and

instruments of this total global war. They certainly counted among its tens of

millions of casualties.3

Britainentry into the war presented the world with a

profoundly transformative reality. At one level, they were all confronted

with the impact of the global economic crisis occasioned by Britain’s decision.

How to manage that crisis was their most immediate concern. At another level,

they were also confronted with the prospect that new military fronts might open

up in Africa and the Asia-Pacific as enemy colonies mobilized their imperial

forces against each other.

Before the German

invasion of Belgium, Luxembourg, and France, many ministers threatened to

tender their resignations if Britain went to war to defend France. After the

invasion on the night of 3–4 August, only two held to that threat. The others

were convinced that a continental war involving Germany was too great a menace

to British interests.4 From this perspective, Britain’s belligerency was

imperative and focussed entirely on containing German

power, although it certainly helped that the German invasion also transgressed

some powerful public norms about war.

Britainentry into the war (especially the US following) registered

a decisive shift towards all experience levels. On 7 August, for example, the

Colombian newspaper La Linterna described the

expansion of warfare as a horrendous catastrophe that can only end with the

definitive destruction of Europe, or perhaps the total ruin of the old

western civilization. By 20 August, it was clear that the war could not be

contained within Europe. La Linterna registered this

shift and its potential impact as follows: we are on the eve of a terrible

economic crisis that can only have fatal results.5 What might happen next,

however, remained unclear: the fog of war emitted a haze of unpredictability.

What did happen next was a violent reshaping of the global economy and the

world of war. Over the next few months, as a military stalemate developed

between the European belligerents, a short-war ambition turned into a long-war

reality. While most contemporaries clung on to the hope that the war would come to a speedy conclusion, the fact that the world’s

foremost economic and naval power was now at war effectively ensured that the

war would not be over by Christmas.

The rather

ill-conceived desire for a short war that could quickly remove the German

invaders from France and Belgium was paramount for these politicians. In their

public rhetoric, they indeed expressed their faith that the war ‘would be over

by Christmas.’ Of course, the possibility that the conflict might evolve into a

protracted affair was a risk they willingly took, much as the Austro-Hungarian,

German and Russian leaderships had also done in the preceding days. Still,

while these men might have imagined the prospect of an all-out war between

Europe’s industrial powers at heart, they also expected that the war would not

radicalize in that way. None of the governments that went to war in July and

early August 1914 were eager to engage in a drawn-out conflagration. None of

them had planned for such a scenario. No strategic plans even existed for

warfare between the imperial rivals in Africa; for example, Instead, they

pinned their short-war ambitions to a small number of decisive military

victories in Europe. Ideally, the continental war would last a matter of weeks,

at most a few months.6

Britain’s century of

neutrality between 1815 and 1914 had enabled its empire to bourgeon. By 1900,

the British crown ruled more than 446 million subjects.7 On the night of 4

August 1914, all 446 million-plus officially went to war. So too did the Royal

Navy. And because the British Empire went to war, so did the outposts of the

French and German empires, drawing in several more imperial subjects formally

into the war. As of 4 August 1914, the world’s seas and oceans became potential

warzones too. If Germany’s invasion of neutral Belgium concerned neutrals on a

conceptual level, Britain’s declaration of war sent the global economy into a

tailspin, taking almost everyone along with it. After 4 August 1914, the entire

world economy was at war.8

How essential the

impact of Britain’s war declaration was as a globally transformative moment is

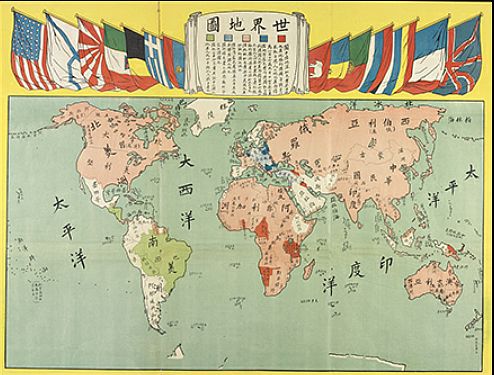

ably illustrated by Kathryn Meyer’s fascinating history of the Chinese treaty

port of Shanghai.9

In 1914, Shanghai was

a ‘city of strangers,’ a critical international port of trade and commerce that

thrived in the nineteenth-century age of open seas and open commerce. Both

Britain and the United States had acquired official concessions from China to

run parts of the port. At the same time, the city’s administration was split

between various local, imperial Chinese, and foreign interests. Wealthy

merchant families primarily ran Shanghai, but the transnational Chamber of

Commerce that represented the city’s various mercantile, industrial, and

banking interests also wielded a considerable amount of power. With Britain’s

declaration of war, this transnational commercial zone could no longer sustain

its networks of interdependence.

The war hit locals

and foreigners alike hard and fast. Firstly, British and German ships left the

port, escaping to the safer havens of Weihaiwei (a

British concession) and Tsingtao (a German concession). All other vessels

delayed their departure. Most of them were unsure of global shipping conditions

or were unable to acquire affordable maritime insurance. They feared seizure by

a belligerent and were uncertain of their destinations’ security and the

economic stability of any markets for their wares. Almost no new ships arrived

in port for weeks. Unemployment skyrocketed. Because there were no ships,

laborers were not needed to unload them. The local silk and tea industries came

to a standstill as there were no foreign buyers for these luxury items. They were

stockpiled up in the port. Inflation hit on imported goods but also staples

like rice.

Money became scarce,

gold and silver prices shot up, and gold shops closed. International business

came to a standstill. The Shanghai stock market shut down and never reopened.

Shanghai’s telegraph stations refused to transmit coded messages to protect China’s

official neutrality declared on 6 August. The transnational Chamber of

Commerce, including its neutral Chinese, Japanese and American, and belligerent

British, French, and German representatives, met to discuss suitable and

cooperative solutions on 8 August. Their negotiations failed, and the Chamber

dissolved.10

Everyone in Shanghai

hoped for a short war. They recognized a short-term economic crisis as

manageable; a long-term one was not. Only in early 1915, as the short-war

illusion dissipated, did the formally neutral port of Shanghai entrench its

commercial activities along belligerent lines. By late 1915, the British and

Americans set up their nation-specific Chambers of Commerce. Germans in

Shanghai could no longer bank with British firms or purchase insurance from

them. Joint-stock companies wound up their business.11

Over the ensuing war

years, the Japanese and American presence in Shanghai increased, and China

asserted more sovereign and economic power over the port’s future, in part

ennobled by a ‘new and patriotic language of trade.’ Like many other

non-European and neutral societies, China gained economically from supplying

the war needs of the European belligerents and from the removal of foreign

competitors in its regional economy. All of these opportunities only became

apparent; however, once the long-war reality set in.12

No civilian community anywhere was safe

Shanghai’s story was replicated all around

the world. In Europe, stock market jitters first appeared with the Austro-Hungarian

ultimatum to Serbia on 23 July and entrenched when it declared war on 28 July.

By 1 August, most European stock markets were closed. So was Wall Street. Tokyo

followed suit. Panic ensued. As the middle classes worldwide recognized the financial

dangers of a global war, they attempted to empty their bank accounts. Gold,

silver, and copper disappeared from circulation as everyone hoarded what was

acknowledged as a more valuable species of exchange. Governments closed their

treasuries, and banks shut their doors, fearing depletion of their reserves.13

Emergency paper money was issued to cover basic transactions, often for the

smallest denominations. The aim was to avoid economic collapse and disaffection

among populations. Prices soared while markets and shops emptied of wares.

There was no clarity on when new supplies would arrive. Nervousness and anxiety

permeated the globe. For example, in Peru’s isolated Canete valley, a three- or

four-day horseback journey from Lima, the prefect called local merchants an

emergency meeting on 10 August to avoid food shortages and rioting. Meanwhile,

banks and factories closed in the Peruvian cities, unemployment spread, and

food prices mounted.14

The Japanese

government felt compelled to subsidize the local silk industry to lose its

profits.15 Cotton farmers in the southern United States would recoup their 1914

losses once trade with Britain, France, and the European neutrals could resume.

Still, in August 1914, they were only fearful of a complete collapse of their

industry.16

Shanghai’s cotton

weavers sourced new cotton supplies from the Chinese mainland in 1915,

illustrating how enterprising individuals could and did profit from the

changing economic landscape of war.17 In August 1914, as African cash crops

accumulated on docks, locals outed their frustrations by rioting and looting.

For example, social unrest permeated British-controlled Nigeria once it became

clear that palm oil and palm kernels could no longer be traded with their main

pre-war markets in Germany. Colonial authorities across the continent were duly

concerned. But given that imports of European manufactured goods also ground to

a halt– a more permanent development – long-term inflationary pressures were

guaranteed. Although they could not know this at the time, this war for

resources would only radicalize after 1914, accentuating the strains on workers

and their families alike.

At no time between

1815 and 1914 were there so many great power belligerents or so many powerful

navies at war with each other. While the rights and expectations of neutrals

were more clearly defined by international law in 1914 than ever before, the

changing ratio of neutrals-to-belligerents expanded the uncertainty. Only the

United States, the Ottoman empire, and Japan were left as great neutral powers

on 5 August. Of the three, only the United States would remain a great neutral

power by the end of the year. In this light, Germany’s invasion of neutral

Belgium signaled further uncertainty for the security of the world’s many more

minor and weaker neutral states and their imperial outposts.

Britain also declared

all-out warfare on German and Austro-Hungarian trade, blockading Germany’s

ports from afar and seizing all merchant vessels flying a German or

Austro-Hungarian flag. The German merchant marine disappeared from the world’s

oceans within days. Most of it would eventually be reflagged by enterprising

neutral companies.18

The German

leadership, for its part, had planned more effectively for a war with Britain,

even if it had not expected the British to go to war. While Germany’s armies

invaded neutral Belgium, it avoided an invasion of its other western neutral

neighbor, the Netherlands, to maximize its access to the substantial Dutch

network of global trade. The Netherlands and the other border neutrals in

Scandinavia and Switzerland would offer Germany an economic ‘windpipe’ through

which it could breathe, as General von Moltke planned when he revised the

Schlieffen Plan in 1909.19 Throughout the war, these same border neutrals were

considered the bane of the Allied blockade. But on 4–5 August 1914, these

neutrals were as economically and psychologically distressed as the rest of the

world.

Beyond the seas,

Europe’s colonial empires also went to war on 5 August. Most

nineteenth-century conflicts between the

European states purposely avoided spill-over into their colonial empires.

But as a belligerent,

the British empire was too formidable not to take the war to its much weaker

German imperial rival. The opportunity to eradicate and acquire the German

empire presented an enticing prospect for the British and French governments,

upon which they quickly capitalized. New Zealand soldiers were asked to invade

the islands of German Samoa, which they completed on 29 August, without loss of

life. An Australian force acquired German New Guinea on 11 September.20 In

Africa, German Togoland fell on 26 August to a combined French-British force.

Cameroon’s German ports were occupied in September, while German South-West

Africa was invaded by South Africans that same month too. It submitted to

British control in the middle of 1915.21

The African continent

remained at war until 1918, costing millions of people their lives and

livelihoods, particularly in southeast Africa. The military campaigns pitting

the predominantly African army of the German Lieutenant-Colonel Paul von

Lettow-Vorbeck against British- and (later) Portuguese-led forces decimated

local communities in a prolonged war of attrition. Central Africa too sustained

long-term military campaigns between Belgian and German troops, with a decisive

impact on locals.

In Europe, Africa,

and the Middle East, more than 18 million men took up arms in late July and

early August 1914. Millions more volunteered for military service over the

coming months; others were forcibly conscripted. Aside from the emotional shock

mobilization engendered in these families and communities, let alone the

cataclysm of violence many of them would soon experience, the removal of so

many men from the civilian workforce had a decisive impact. It also militarized

familial and communal settings. Uniforms and military declarations dominated

civilian life in many communities after August 1914. The white British

Dominions were particularly enthusiastic in mobilizing for the war. While

Ireland and South Africa posed some issues, not least when a group of

opportunistic Afrikaners under the leadership of Niklaas’ Siener’ van Rensberg attempted to take over the government (a rebellion

that was quickly repressed by the local authorities), even here, the call for a

war against ‘barbaric’ Germany was well supported.22 Among non-white subjects

of the British and French empires, the mobilization for war was generally

received with more circumspection and recognition that the war offered

opportunities to advance a range of political ambitions, be they in support of

or against the Anglo-European imperial authorities.

Some Maori, for example, saw a possibility in loyally serving

King and empire to gain greater political recognition as full citizens of

Aotearoa, New Zealand.23 Some Australian Aborigines, Polynesian, Caribbean,

Vietnamese, Cambodian, Algerian, and Canada’s First Nation communities

mobilized to support their empire’s war effort for similar reasons: the promise

of more excellent political representation and racial equality, and recognition

within the kingdom and local polity.24 In India, too, numerous elites argued in

favor of war to advance their status as loyal imperial subjects worthy of

greater self-governance and possible Dominion status.25 The opening months of

war thus reflected the equivalence of Burgfrieden and

expressions of national honor in several colonial outposts. Support for an

embattled empire would (so these supporters thought) only lead to political

advantages within the empire once the war finished. Their loyalty to the empire

seemed well-founded, particularly when they were endorsed by supportive appeals

from the imperial authorities themselves. That motivation remained for many

months, sometimes years. Much of it would not survive the whole war.26

Other indigenous and

colonized communities who looked to advance their pre-existing anti-imperial

agendas were equally alert to the geostrategic opportunities presented by the

outbreak of global war. Many south-east Asians had a nuanced understanding of the

war’s global implications and geostrategic parameters. Whether they were

formally neutral (as was the case for China, Siam, and the Dutch East Indies)

or formed part of a belligerent empire (as was the case for Singapore,

Malaysia, and French Indo-China), the global war influenced how these

communities considered and reconfigured their political and economic interests

after 4 August. As the historian Heather Streets-Salter highlights, many

anti-French and anti-British revolutionaries in Southeast Asia successfully

lobbied for German government support to fund and resource their resistance

activities against their common enemy. They often did so from neutral

territories. These activities helped destabilize the British and French wartime

empires in due measure.27

Many communities in

Africa and the Middle East also understood how the war altered their futures.

As early as August 1914, Tutsi tribes in German-controlled Rwanda raided their

Hutu neighbors in the Belgian-held Congo, utilizing the imperial governments’

belligerency as part of their rationale.28 This local war escalated so that by

1916 a Belgian-led Force Majeure from the Congo, peopled mainly by local

soldiers, invaded German Rwanda and Burundi and successfully seized Tabora in

September. The Belgian government formally extended a protectorate over Rwanda

on 6 April 1917.51 For many African and Middle Eastern communities, the world’s

war thus became part and parcel of their local and imperial rivalries.

Similarly, after the Ottoman entry into the war, several Kurdish communities

mobilized in support of the empire, helping to occupy Russian-controlled

Azerbaijan and raiding and razing local Nestorian Christian communities, who

supported their co-religionist Russians and attacked the Muslim Kurds in turn.

However, for the

Persian (Iranian) government, the outbreak of war was disastrous. Aiming to

protect Persia’s sovereign independence, it declared formal neutrality. But

since a belligerent Russia occupied the northern reaches of Persia and a

hostile Britain administered the southern region, remaining non-belligerent

proved impossible. Both powers eyed up Persia’s oil reserves. Meanwhile, for

the Swedish police troops already serving in Persia as neutral peacekeepers

(they were there to train police officers, aid with tax collection, and combat

brigandage), the dangers were deemed too great. After declaring Sweden’s

neutrality in the war, its government recalled the entire force back to Sweden.

Persia became a key waterfront. Representatives of the great power belligerents

repeatedly negotiated with local communities, including Kurds, Assyrians,

Armenians, Azerbaijani, and Muslim groups, for their support in an attempt to

destabilize their enemies’ interests.29 These deals prevented the Persian

government from sustaining effective rule and had long-term legacies for the

stability and political cohesion of the region after 1918. Persia, then, was

the third neutral state (after Belgium and Luxembourg) to fall victim to the

great powers’ war. It was not the last.

Britain’s war

declaration presented the Japanese government with a tantalizing prospect. With

much of Europe at war, virtually all of Japan’s imperial rivals in the

Asia-Pacific region (aside from the United States) were pre-occupied. Given

that Japan could legitimately call upon its formal alliance with Britain to go

to war with Germany, it faced the possibility of expanding its Asia-Pacific

empire without much opposition. Japan declared war on Germany on 27 August

1914. It attacked and occupied the German-Chinese treaty port of Tsingtao,

which fell on 7 November, and acquired the Marshall, Mariana, and the Caroline

Islands, and the Jaluitt Atoll by the end of the

year. The Japanese Navy further patrolled the Pacific and Indian Oceans,

hounding what was left of the German navy out of these seas, convoying British

and French troopships, and securing these waters for the safe passage of merchants

vessels. The regional Asia-Pacific economy primarily grew during the war

because of Japan’s protective role. While the Atlantic Ocean, the

Mediterranean, Baltic, and Black Seas would become increasingly treacherous to

navigate, the Pacific and Indian Oceans remained relatively safe zones for

shipping. That Japan was the ultimate beneficiary of these developments was almost

inevitable. The longer Europe’s war lasted, the greater Japan’s economic gains.

In China, the shift

to global warfare on 4–5 August 1914 registered as weiji

(great crisis, literally ‘danger opportunity’). The loss of European imperial

agency in the region meant that only the American government was left to

protect the ‘open-door policy that had dominated Chinese foreign and economic

relations throughout the previous two decades. Japan’s invasion of Tsingtao

frightened the Chinese. Their fears were fully realized when Japan capitalized

on its position of power by issuing a set of twenty-one demands expanding

Japanese control over Tsingtao, Manchuria, and Chinese economic affairs for the

foreseeable future. The twenty-one demands signed by China in March 1915 are

considered one of China’s ignoble moments. For the United States, too, Japanese

belligerency and expansionism during the war heightened the rivalry between

these two major Pacific powers. Meanwhile, Japan’s notion might threaten other

Asia-Pacific communities that permeated the region. Still, as the historian Xu Guoqi shows, the changing landscape of imperial order in

the Asia-Pacific region was also an opportunity for the Chinese to reassert

themselves into the international diplomatic order.30

If Japan’s war

declaration was unimaginable without Britain’s entry into the war, so too was

the Ottoman empire. Until Britain joined the war, the Young Turk government

could imagine itself as a neutral power situated on the periphery of a European

continental war. With Britain’s entry into the war, the geostrategic threats to

the empire mushroomed, as did the possibility that the victors (on either side)

would not hesitate to dismember the empire at the conflict’s conclusion. Since

Russia presented the most significant threat, a war was fought on the Allies’

side. War on the side of the Central Powers offered a wealth of opportunities,

not least the possibility to expand and Turkify the empire.31 From early August

1914, the Ottoman government negotiated an alliance with the Central Powers,

promising military aid against Russia at the earliest opportunity. It took

until late October to fulfill this secret promise.32 On attacking the Russian fleet in the

Black Sea on 29 October, the vast Ottoman empire with its immensely diverse

population went to war. It opened up new military fronts in the Caucasus,

Mesopotamia, and Persia made the Suez Canal less safe and cut Russia off from

the Mediterranean Sea.33

Even if opportunism

drove its decision to enter the war, the Ottoman government publicly presented

the war as a defensive enterprise.34 Much like Christianity was mobilized as a

rationale for war, and in the defense of ‘civilization’ in Europe, the Ottoman

sultan declared jihad (holy war) on all Christians in early November. Jihad had

numerous faces aimed at mobilizing Muslim subjects of the Ottoman sultan in a

‘just’ and ‘necessary’ war and inspiring Muslim subjects of enemy empires to

incite anti-imperial rebellion from below. Jihad confronted all the Christian

powers, including the neutral Netherlands, whose East Indian colonies counted

millions of Muslims. With good reason, the British and French colonial

authorities worried about the potential impact of jihad on a colonial rebellion

among their Islamic subjects. Across Africa, south and south-east Asia, Muslims

were inspired by the jihad to reassess their relationships to the local

imperial authority and the broader world at war.

There is much

historiographical debate about the success of the 1914 jihad declaration.35 At

one level, jihad legitimated certain wartime actions, not least the systematic

targeting of Christian populations within the Ottoman realm. Christian-Muslim

relations in the Middle East, which were shaky at the best of times,

drastically declined after August 1914.36 There is also evidence to suggest

that for some Muslims, the call to battle helped to solidify their support for

the Ottoman war effort. But jihad also validated a massive Turkification

enterprise throughout the empire. Because only loyal subjects to the empire

could be trusted and pre-empt the creation of ‘fifth-column guerilla forces,

the Ottoman government ordered the massive displacement of ‘suspect’ civilians,

including millions of Christians. Through 1915, these Christians would be

systematically eliminated by the Ottoman government in a distinctly genocidal

campaign. However, identifying the ‘enemy within’ was a common strategy

utilized in all belligerent societies and one that reflected widespread

colonial imperial practices before the war.

In the war’s opening

months, the giddy heights of the short-war ambition were reached. Thus,

Japanese hopes for a sizeable Asian empire and recognition of their great power

status and the Chinese government’s wish to reinsert itself in the

international arena were equally prominent ambitions in the war’s opening

months. So too were Vietnamese hopes for independence and many indigenous

communities’ desires to achieve political recognition for their wartime

military service, Indian and Irish hopes for Home Rule, and even some

suffragettes to earn the vote for women. The expectation that wartime service

and support could lead to post-war gain were all too common in the 1914 war

months.

In Europe, stock

market jitters first appeared with the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum to Serbia on

23 July and escalated when it declared war on 28 July. By 1 August, most

European stock markets were closed, and Tokyo followed suit. Panic ensued. As

the middle classes recognized the dangers of a global war, they attempted to

empty their bank accounts. Emergency paper money was issued to cover basic

transactions.

No civilian community

anywhere was prima facie safe from the destructive violence.

1. Holger Herwig,

‘Germany and the “Short-War” Illusion: Toward a New Interpretation?’ Journal of

Military History 66, 3, 2002, pp. 681–93; Jakob Zollmann,

Naulila 1914: World War I in Angola and International

Law Nomos, 2016, p. 163.

2. William

Philpott, ‘Squaring the Circle: The Higher Coordination of the Entente in the

Winter of 1915–1916’ English Historical Review 114, 458, 1999, pp. 875–7.

3. Cf Dick Stegewerns, ‘The End of World War One as a Turning Point in

Modern Japanese History’ in Bert Edström, ed., Turning Points in Japanese

History Japan Library, 2002, pp. 138–40; Carl Strikwerda, ‘World War I in the

History of Globalization’ Historical Reflections 42, 3, 2016, p. 112; Kai

Evers, David Pan, ‘Introduction’ in Kai Evers, David Pan, eds, Europe and the

World: World War I as Crisis of Universalism Telos Press, 2018; David Reynolds,

The Long Shadow: The Great War and the Twentieth Century Simon & Shuster,

2013; Eric Hobsbawm, Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century 1914–1991

Penguin, 1994.

4. Isabel V.

Hull, A Scrap of Paper: Breaking and Making International Law during the Great

War, 2014 p.local merchants an emergency meetinge British Government’s Decision for War in 1914’

Diplomacy & Statecraft 29, 4, 2018, pp. 543–64.

5. Both quotes in

Jane M. Rausch, Colombia and World War I: The Experience of a Neutral Latin

American Nation during the Great War and Its Aftermath, 1914–1921 Lexington

Books, 2014, p. 26.

6. For an excellent overview of these global

ramifications: Richard Roberts, ‘A Tremendous Panic: The Global Financial

Crisis of 1914’ in Andrew Smith, Simon Mollan, Kevin D. Tennent, eds, The Impact of the First World

War on International Business Routledge, 2017, pp. 121–41.

7. Mark

Harrison, The Economics of World War II: Six Great Powers in International

Comparison, 2000, pp-6-7.

8. Stephen Broadberry (Editor),

Mark Harrison (Editor) The Economics of World War I, 2005.

9. Kathryn Meyer, ‘Trade and Nationality at Shanghai upon

the Outbreak of the First World War 1914–1915’ International History Review 10,

2, 1988, pp. 238–60.

10. F.V. Meyer, International Trade Policy (Routledge

Library Editions: International Trade Policy), 2017.

11. Global banking

systems were similarly affected: Strikwerda, ‘World War I’ p. 121.

12. Meyer, ‘Trade’; D.K. Lieu, The Growth and

Industrialization of Shanghai China Institute of Economic and Statistical

Research, 1936, esp. pp. 11, 19, 23.

13. Martin Horn,

Britain, France, and the Financing of the First World War McGill-Queen’s

University Press, 2002, p. 29; Bailey, ‘Supporting’ p. 28.

14. Bill Albert,

South America and the First World War: The Impact of War on Brazil, Argentina,

Peru and Chile Cambridge University Press, 1988, p. 1. Also: Abbenhuis, Morrell, First Age pp. 185–6.

15. Ushisaburo Kobayashi, The Basic Industries and Social

History of Japan 1914–1918 Yale University Press, 1930.

16. Cf Roberts,

‘Tremendous’ p. 135.

17. Cotton

Mills in China’ Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 9 July 1915, p. 769.

18. Osborne, Britain’s p. 61.

19. Marc Frey,

‘Trade, Ships and the Neutrality of the Netherlands in the First World War’

International History Review 19, 3, 1997, p. 543.

20. Charles

Stephenson, Germany’s Asia-Pacific Empire Boydell Press, 2009, p. 100.

21. Steinbach,

‘Defending the Heimat’ pp. 179–208.

22. Bill Nasson,

‘Africa’, in Jay Winter, ed., Cambridge History of the First World War Volume

1, Cambridge University Press, 2014, pp. 445–6.

23. Alison

Fletcher, ‘Recruitment and Service of Maori Soldiers

in World War One’ Itinerario 38, 3, 2014, pp.

59–78.

24. Jennifer D.

Keene, ‘North America’ in Winter, ed., Cambridge History Volume 1, p. 523; Guoqi, ‘Asia’ p. 487; Samuel Furphy, ‘Aboriginal

Australians and the Home Front’ in Kate Ariotti,

James Bennett, eds, Australians and the First World War: Local-Global

Connections and Contexts Palgrave MacMillan, 2017, pp. 143–64; Reena N. Goldthree, ‘A Greater Enterprise than the Panama Canal:

Migrant Labor and Military Recruitment in the World War I-Era Circum-Caribbean’

Labor 13, 3–4, 2016, pp. 63–4.

25. Das, India

p. 41.

26. For example:

Humayun Ansari, ‘“Tasting the King’s Salt”: Muslims Contested Loyalties and the

First World War’ in Hannah Ewence, Tim Grady, eds,

Minorities and the First World War Palgrave MacMillan, 2017, pp. 33–61.

27. Streets-Salter,

World War One.

28. Rik Verwast, Van Den Haag tot

Geneve: België en het Internationale Oorlogsrecht

1874–1950 Die Keure, pp. 80–4.

29. T. Atabaki, ‘The First World War, Great Power Rivalries and

the Emergence of a Political Community in Iran’ and M. Ettehadiyyeh,

‘The Iranian Provisional Government’ both in Touraj,

ed., Iran pp. 1–7, 9–27; Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, ‘The British Occupation of

Mesopotamia 1914–1922’ Journal of Strategic Studies 30, 2, 2007, pp. 349–77.

30. Guoqi, ‘Asia’ p. 483.

31. Kramer, Dynamic

p. 144.

32. Aksakal, ‘Ottoman

Empire’ p. 473.

33. Bailey,

‘Supporting’ p. 29.

34. Erik-Jan Zürcher, ‘Introduction’ in Erik-Jan Zürcher,

ed., Jihad and Islam in World War 1: Studies on the Ottoman Jihad on the

Centenary of Snouck Hurgronje’s

‘Holy War Made Germany’ Leiden University Press, 2016, p. 14.

35. Zürcher, ‘Introduction’ p. 22.

36. Bruinessen, ‘A Kurdish’, p. 70.

For updates click homepage here