By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

Annual 2023 Forecast

This year's central

issue will be the ongoing spasm of economic dysfunction due in equal parts to the

war in Ukraine, post-pandemic recovery efforts, and the more banal aspects of

normal business cycles. The dramatic economic crisis in China compounds these

problems, its effects inevitably transmitting worldwide by China's economic

weight. Global, multifaceted economic crises like these take years to resolve,

and in their resolution, they will generate political consequences within

countries and between them. This phenomenon will intensify in 2023. And though

the war in Ukraine is agonizing to observe, it is not the most important issue

we face this year. That honor belongs to China.

China

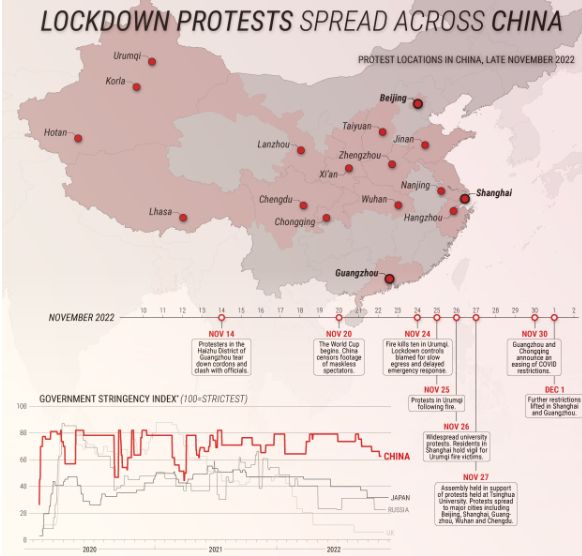

As expected, China’s

economic crisis intensified in 2022, leading to higher-profile social unrest.

COVID-19 lockdown measures ostensibly caused them, but as with all protests,

they became broader movements of people airing economic and political

grievances. In some ways, China is a victim of its success. Its breakneck

economic growth was unsustainable, but domestic and international investors

believed it to be permanent, as they're wont to do. China desperately needs

investment capital and unfettered exports to stabilize its system. With the

global economic crisis, both are harder to come by – a fact that has forced

China to redefine its relationship with perhaps the only country able to

provide investment capital and demand for products amid a recession: the United

States.

As indicated by our recent

article, talks between China and the US have yet to be productive, but

we forecast they will be. Beijing will have to ease military tensions with the

United States, save for the normal face-saving theatrics. The U.S. has reason

to play nice too; it doesn’t want China to move closer to Russia, nor does it

want Beijing to act aggressively in the face of economic catastrophe.

For all the

saber-rattling between the two, we do not expect a Sino-American war. China

cannot afford a defeat in a war as its economic standing at home is in

question. Its focus must be on solving its economic problems and quelling

unrest. It will need a reasonable relationship with the U.S. to do that.

The United States

At this point, the

U.S. cannot afford to abandon Ukraine. Having asserted its interests there and

pressured other nations to cooperate, American options are limited. Still,

Washington is fighting an optimal war. The Ukrainians are absorbing casualties,

even as the delivery of U.S. weapons and munitions imposes heavy casualties on

the Russians. Washington will press for a negotiated settlement that keeps

Russia as far from NATO’s borders as possible and will hold this position

through the year.

At home, the U.S.

will experience a significant recession, similar to the 1970s, when the cost of

Vietnam, the Arab oil embargo and natural downturns in the business cycle

created massive inflation and job pressures. This recession, like that one,

will begin to focus on cyclical changes for the decade.

Russia

The war in Ukraine is

gridlocked. Every time the Ukrainian armed forces score a tactical victory,

Russia prevents them from fully exploiting it – and vice versa. This state of

affairs would suggest a negotiated settlement is in the offing, and though we

believe that to be the logical outcome, no one seems willing to budge.

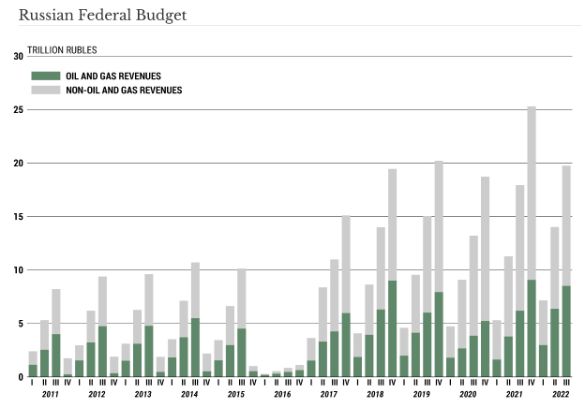

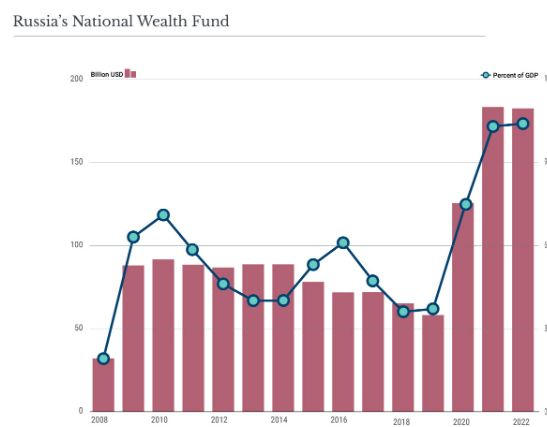

The prospects for a

settlement depend, to some degree, on the viability of the Russian economy. The

West’s initial response to the invasion was a debilitating campaign that, for a

spell, crippled Russia’s economy. Though Russia isn’t out of the woods, it has

rebounded well enough to maintain some leverage in the war, in international

energy markets, and so on.

Economics aside, two major obstacles have

frustrated any attempt to end the stalemate. The first is a precondition that

neither side will resume hostilities at a time of their choosing. Both want to

retain that right. The second is an unwillingness to cede territory, which is

difficult for domestic political reasons. The Ukrainians want control of their

whole country. The Russian public would be appalled that all the death and

hardships were far less than promised. (A key element on both sides of the war

is the management of the public. Ukraine and the U.S. have shown they can

manage their public. Russia is the one to watch.)

There is no reason to

believe that either side will crush the other. There may be peace talks, but a

rapid settlement is unlikely. The stakes are high, and neither side will break.

The most likely course is that the war will continue, but don’t be surprised to

see the beginnings of talks toward resolution.

Europe

It’s difficult to

forecast Europe because "Europe" is ultimately a geographic concept

bound together by multinational organizations, the biggest of which are NATO

and the European Union, each with its membership list and mission. It’s better

to think of Europe as an arena for cooperation and coemption.

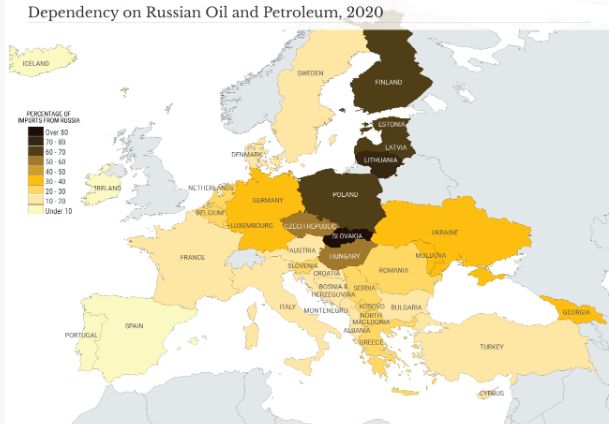

A major issue for

Europe in 2023 will be continued access to Russian energy. Europeans agree that

they need oil, but they need to agree on what price should be paid for it.

Poland opposes any concession to Russia. Hungary doesn’t. Germany is eager to

maintain oil shipments but must subordinate itself to the United States, its

largest customer and guarantor of national security. Consider also that Europe

broadly believes a Russian victory in Ukraine would be bad for the continent.

Countries like Poland, the Czech Republic, and Germany remember the Cold War

and are in no hurry to recreate the boundaries that defined it. There is a

genuine support in governments – and in some publics – for the war.

The European Union was designed for

peace and prosperity. War strains these ideals and skews geopolitical interests

and economic desires. Some countries feel they must prioritize war preparations

over economic considerations. This will strain the unity of the EU in the

coming year, not only over this issue but also over an increasing sense that

the bloc undermines national economic and military interests. The EU will

continue, however slowly, to fragment as national interests diverge.

India

India is slowly

emerging as an economic and military power whose ascension affects everyone. It

has one of the fastest-growing major economies – certainly among comparably

developed and similarly sized economies. It must now be included with nations

that influence the global system.

India's national

strategy is to balance between greater powers, particularly Russia and the

United States, a practice that will inevitably create tensions inside a country

that is famously variegated. India will grow in fits and starts as it manages

its relationships with historical adversaries and skew

ties with traditional

allies. New Delhi will, for example, enhance economic and industrial

cooperation with Russia to balance against China. There have always been

questions as to when India would emerge as a great power. Next year seems the

moment.

The Middle East and North Africa

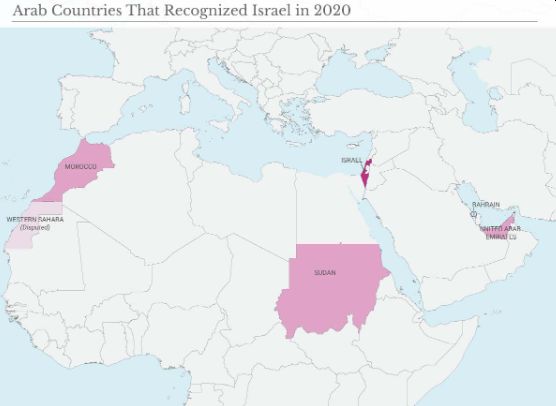

New alliances will

emerge and old ones will decay. Israel has already become a major anchor of the

region, as evidenced by the Abraham Accords, but forces inside the country have

created a degree of unease in Arab nations. More important is the political

future of Turkey, with the Erdogan era waning and the region preparing for new

Turkish policies. Internal matters will dominate the region in 2023 – no small

matter for a region beset by decades of war – and those within Israel and

Turkey most of all. Neither will yield much clarity.

Latin America

Driving the behavior

of Latin America in 2023 will be its inability to recover from the COVID-19

pandemic. It was arguably the worst-hit region and has been the slowest to

recover. Latin American countries will see intense social unrest, and

governments will prioritize foreign ties with economic benefits. Increased

global uncertainty and competition surrounding commodities like food, energy

and metals will spark renewed interest from countries in the Western Hemisphere

to establish commodity-driven commercial ties. Russia and China will not be

able to compete as strongly in Latin America as they have in past years. Their

own economic problems will prevent them from offering financial solutions this

far afield, creating an opportunity for the U.S. to shore up ties, including

with sometimes adversarial governments in Cuba and Venezuela.

Final Comment

It’s easy to forget we’ve lived in the post-Cold War era

for more than 30 years. The world was never perfectly harmonious, but countries

broadly seemed to be paddling in the same direction. 2023 may finally be the

year the world starts to move into another age. Alliances and relationships

will fragment as interests diverge, which could even ease pressure in some

places. Tensions created by the U.S.-China competition will at least partly

shape those interests, even as Beijing and Washington come to some formal

economic understanding and informal military understanding.

For updates click hompage here