By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Russia’s Quest For A Gateway To Iran And

The Middle East

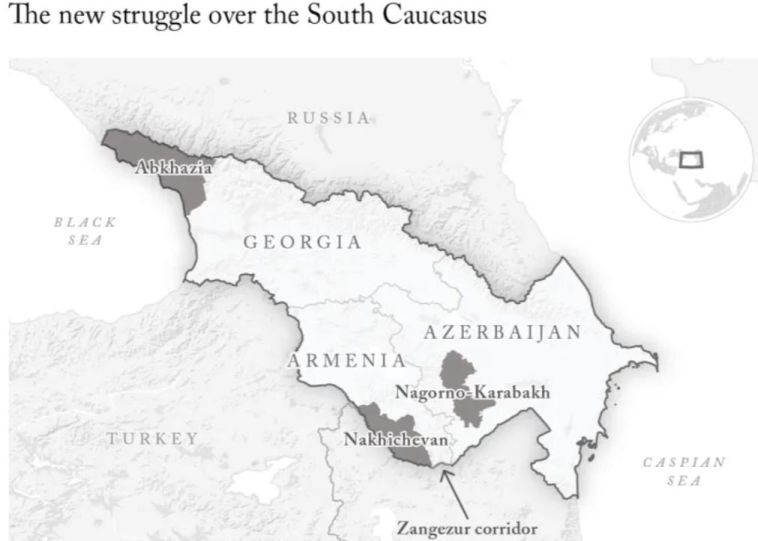

On April 17, a column

of Russian tanks and trucks passed through a series of dusty Azerbaijani towns

as they drove away from Nagorno-Karabakh, the

highland territory at the heart of the South Caucasus that Azerbaijan and

Armenia had fought over for more than three decades. Since 2020, Russian

peacekeepers have maintained a presence there. Now, the Russian flag that flew

over the region’s military base was being hauled down.

Although it caught

many by surprise, the Russian departure further consolidated a power shift that

began in late September 2023, when Azerbaijan seized the territory and, almost

overnight, forced the mass exodus of some 100,000 Karabakh Armenians—while Russian

forces stood by. Azerbaijan, an authoritarian country that shares a border with

Russia on the Caspian Sea, has emerged as a power player, with significant oil

and gas resources, a strong military, and lucrative ties to both Russia and the

West.

Meanwhile, the

region’s other two countries, Armenia and Georgia, have been experiencing

tectonic shifts of their own. In the months since Azerbaijan’s takeover of

Nagorno-Karabakh, Armenia, a traditional ally of Russia, has swung ever more

firmly toward the West. The ruling party in Georgia is breaking with three

decades of close relations with Europe and the United States and seems intent

on emulating its authoritarian neighbors. In May, the Georgian parliament

passed a controversial law to crack down on “foreign influence” over

nongovernmental organizations—a law that derives inspiration from Russian

legislation and sends Moscow a signal that it has a dependable partner on its

southern border.

Obscured in this

reordering of the South Caucasus are the complex motives of Russia itself. The

region—known to Russians as the Transcaucasus—has

held fluctuating strategic significance over the centuries. The imperial touch

was not as heavy there as in other parts of the Russian Empire or Soviet Union.

Following the end of the Soviet Union, Moscow tried to keep its leverage

through manipulation of the local ethnoterritorial conflicts there, maintaining

as many troops on the ground as it could.

But the war in

Ukraine and the Western sanctions regime have changed that calculus. By

deciding to remove troops from Azerbaijan, the Kremlin is acknowledging that

economic security in the South Caucasus—for now at least—is more important than

the hard variety. Russia badly needs business partners and sanctions-busting

trade routes in the south. At a time when it is increasingly squeezed by the

West, it also sees the region as offering a coveted new land axis to Iran.

Baku’s Big Play

At first blush, the

unilateral Russian withdrawal from Nagorno-Karabakh this spring was puzzling.

For much of the past three decades, Azerbaijanis and Armenians have fought over

the territory, which is situated within Azerbaijan but has had a majority ethnic

Armenian population. In 2020, Azerbaijan reversed territorial losses it had

suffered in the 1990s and would have captured Nagorno-Karabakh, as well, were

it not for Russia’s last-minute introduction of a peacekeeping force, mandated

to protect the local Armenian population. Those peacekeepers stood by, however,

as Azerbaijan marched into Karabakh last September. Still, they had a mandate

to stay on until 2025. As well as projecting Russian power in the region, they

could also have facilitated the return of some Armenians to Nagorno-Karabakh.

Of course, for

Russia, the 2,000 men and 400 armored vehicles that were transferred out of the

territory provide welcome reinforcements for its war in Ukraine. But that was

not the whole story. By deciding to leave the region, Russia handed Azerbaijan

a triumph, allowing its military to take unfettered control of the

long-contested territory. For most Armenians, it was a fresh confirmation of

Russia’s abandonment. Almost immediately, observers speculated that some kind

of deal had been struck between Russia and Azerbaijan.

As the largest and

wealthiest of the three South Caucasus countries, Azerbaijan has profited most

from Russia’s shift. It is a player in East-West energy politics, providing oil

and gas that is carried by two pipelines through Georgia and its close ally Turkey

to European and international markets. Sharing a border with Iran, it also

serves as a north-south gateway between Moscow and the Middle East. It helps

that the Azerbaijani regime—in contrast to Armenia’s democratic government—is

built in the same autocratic mold as Russia’s. Ilham Aliyev, Azerbaijan’s

longtime strongman president, has even deeper roots in the Soviet nomenklatura

than does Russian President Vladimir Putin: his father was Heydar Aliyev, a

veteran Soviet power broker who was also his predecessor as the leader of

post-independence Azerbaijan, running the country from 1993 to 2003. The

younger Aliyev and Putin also know how to do business together, in a

relationship built more around personal connection and leadership style than on

institutional ties.

Relations were not

always so good. In tsarist and Soviet times, Moscow took a more overtly

colonial approach toward the Muslim population of Azerbaijan, giving Russian

endings to surnames and imposing the Cyrillic script on the Azeri language.

Azerbaijanis still resent the bloody crackdown in 1990, when, during the last

days of the Soviet Union Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev sent troops into Baku

to suppress the Azerbaijani Popular Front Party, killing dozens of civilians.

During much of the long-running Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, Moscow gave more

support to the Armenians.

After the 2020

Nagorno-Karabakh war, however, Russia began a new strategic tilt toward

Azerbaijan. The withdrawal of peacekeepers this spring looks like the key

component of a full Baku-Moscow entente. Just five days after the Russian

peacekeepers left, Aliyev traveled to Moscow, where he discussed enhanced

north-south connections between the two countries. After the talks, Russian

Transport Minister Vitaly Savelyev said that Azerbaijan was upgrading its

railway infrastructure to more than double its cargo capacity—and allow for

much more trade with Russia.

For Moscow, this is

all part of a race with the West to create new trade routes to compensate for

the economic rupture caused by the war in Ukraine. Since the war started,

Western governments and companies have been trying to upgrade the so-called

Middle Corridor, the route that carries cargo from western China and Central

Asia to Europe via the Caspian Sea and the South Caucasus—thereby bypassing

Russia. For its part, Russia has been trying to expand its own connections to

the Middle East and India via both Georgia and Azerbaijan.

Azerbaijan, thanks to

its favorable geographical position and nonaligned status, has been able to

play both sides. It is a central country in the Middle Corridor. It is

increasing gas exports to the EU, after a deal with the European Commission in

2022. But it is also ideally positioned to trade with Russian energy exporters,

too. In a report released in March, the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies

suggested that Azerbaijan, working with its close ally Turkey, could help

create a hub for Russian gas to reach foreign markets without sanction. And

because of Azerbaijan’s growing status as the regional power broker, it also

could enable Russia to realize its aims of building stronger connections to

Iran.

Trains To Tehran

A key part of

Russia’s shifting ambitions in the South Caucasus is to rebuild overland

transport routes to Iran. The most attractive route is the one that Azerbaijan

calls the Zangezur Corridor, a projected road and

rail link through southern Armenia that would connect Azerbaijan to

Nakhichevan, an Azerbaijani exclave that borders both Iran and Turkey. By

reopening the 27-mile route, Moscow would have a direct rail connection to

Tehran, which has become an important arms supplier to Russian forces fighting in

Ukraine.

This north-south axis

would effectively revive what was known as the Persian Corridor during World

War II—a road-and-rail route running north from Iran through Azerbaijan to

Russia that supplied no less than half the lend-lease aid that the United

States provided the Soviet Union during the conflict. By a strange twist of

fate, this same axis is now vital to Moscow in its current struggle against the

United States and the West.

Back in November

2020, the Russians thought they had a deal to get this route open when Putin,

Aliyev, and Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan

signed a trilateral agreement that formally halted that year’s conflict in

Nagorno-Karabakh and introduced the Russian peacekeeping force. The pact

included a provision calling for the unblocking of all economic and transport

links in the region, and it specifically mentioned the route to Nakhichevan

across Armenia. Moreover, it also stated that control over this route would be

in the hands of Russia’s Federal Security Service, or the FSB.

Since then, the

corridor has remained closed because Armenia and Azerbaijan could not agree on

the terms of its operation. Yet Russia’s insistence that its security forces

should be in control has remained constant. On his return from Moscow in April,

Aliyev also alluded to this, telling an international audience that the 2020

agreement (whose other provisions are all now redundant) “must be respected.”

Opening the corridor, then, may be the essence of the new deal between

Azerbaijan and Russia: in return for Russia pulling its forces out of

Karabakh—a step that handed the Azerbaijani leadership a major domestic

victory—Azerbaijan may acquiesce to Russian security control over the planned

route across southern Armenia.

If such a plan is carried

out, it would amount to a coordinated Azerbaijani-Russian takeover of Armenia’s

southern border—a nightmare for both Armenia and the West. The Armenians would

lose control of a strategically vital border region. The United States and its

Western allies would see Russia take a big step forward toward establishing a

coveted overland road and rail link with Iran. Moreover, Armenia on its own

lacks the capacity to prevent Russia and Azerbaijan from acting.

Armenian Alienation

No former Russian

ally has seen such a dramatic breakdown in its relations with Moscow as

Armenia. The two countries have a long historical alliance built on their

shared Christian religion. Russia was the traditional protector of Armenians in

the Ottoman Empire, and Armenians who lived in the Russian Empire and then the

Soviet Union tended to enjoy more upward social mobility than other non-Slavs:

some of them reached the highest echelons of the Soviet elite.

But all that has

changed over the past few years. Russian relations

with Armenia began to cool off in 2018, when Armenia’s Velvet Revolution

brought Pashinyan, a populist democrat, to power.

That transition was barely tolerated in Moscow, which feared another “color

revolution” bringing an unfriendly government to power on its border. After the

Nagorno-Karabakh war in 2020, Moscow continued to support the Armenians, but

relations were increasingly strained. For Yerevan, Azerbaijan’s seizure of the

territory last fall, with Russian acquiescence, became the last straw.

As the Kremlin failed

to honor its security commitments to Armenia, Pashinyan

began to move his country decisively toward the West. Last fall, he met with

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and pushed Armenia to formally join the

International Criminal Court, meaning that Putin, who has an ICC arrest warrant

on his head, could theoretically be arrested if he sets foot in Armenia. And in

February, Pashinyan also suspended Armenia’s

participation in the Russian-led military alliance, the Collective Treaty

Security Organization. Some European politicians have now mooted the idea of

eventual EU membership for Armenia.

With Nagorno-Karabakh

removed from the equation, Pashinyan is also pressing

harder to reduce his country’s dependence on Russia. Armenia has asked Russia

to remove the Russian border guards who have been stationed in Armenia’s Zvartnots airport since the 1990s by August 1. Other

Russian border guards who are stationed on Armenia’s borders with Iran and

Turkey will stay for now, but the deployment in 2023 of an EU civil monitoring

mission in southern Armenia shows where the Armenian government’s strategic preferences

lie.

Ethnic Armenians fleeing to Armenia following

Azerbaijan's seizure of Nagorno-Karabakh, September 2023

Armenia’s pivot to

the West, however, comes at an extremely unfavorable moment. Flush with victory

and benefiting from strong ties with both Russia and Turkey, Azerbaijan shows

no signs of letting up its pressure on Armenia. Meanwhile, the other big regional

powers around Armenia—Iran, Russia, and Turkey—are aware that the West is

overextended. Despite their many differences, they have a common agenda, shared

with Azerbaijan, to cut down the West’s strategic profile in the region and

elevate their own. In April, for example, top U.S. and European officials in

Brussels announced an economic aid package for Armenia. In response, Iran,

Russia, and Turkey each issued almost identical statements deploring the West’s

dangerous pursuit of “geopolitical confrontation,” by which they meant Western

intervention in Armenia.

The new confrontation

over Armenia is not just a matter of posturing. Pashinyan’s

government has evidently concluded that its future lies with the West. Although

this shift makes sense in the longer term, it carries many shorter-term risks.

Armenia is overwhelmingly dependent on Russian energy and Russian trade: Moscow

supplies 85 percent of its gas, 90 percent of its wheat, and all the fuel for

its lone nuclear power plant, which provides one-third of Armenia’s

electricity. And Armenia’s own economy is still heavily oriented toward the

Russian market. These ties give Moscow enormous economic leverage; it could

seek to bend the country to its will by sharply raising energy prices or

curtailing Armenian trade.

Meanwhile, Armenian

officials and experts fear even more direct military threats to the country’s

sovereignty. One is that Azerbaijan, in coordination with Russia, has the

military capacity to seize control of the Zangezur

Corridor by force, if it chooses to, in a few hours. Another is that rogue

domestic forces in Armenia, with foreign backing, could try to overthrow the Pashinyan government by violence or organized street

protests in an effort to destabilize the country and allow a more pro-Russian

government to take power.

These threats come in

parallel to diplomacy. Azerbaijan continues to pursue bilateral talks with

Armenia to reach a peace agreement to normalize relations between the two

countries. Whether the two historic adversaries can avoid sliding back into war

depends largely on the extent to which Western powers, despite their

commitments in Ukraine, are prepared to invest political and financial

resources to underwrite such a settlement.

Georgian Ambiguity

As if the threat of a

dangerously weakened Armenia and a new Russian-Iranian land corridor were not

enough, the West also faces a growing challenge from Armenia’s neighbor

Georgia. As Armenia tries to move West, the government of Georgia, a country

that has enjoyed huge support from Europe and the United States since the end

of the Cold War, is seemingly doing the opposite.

Post-Soviet Russia

has a long history of meddling in post-Soviet Georgia, and most Georgians

retain a deep antipathy to Moscow. In 2008, Georgia cut off diplomatic

relations after Russian forces crossed the border and recognized the two

breakaway territories of Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent. A 2023 poll

found that only 11 percent of Georgian respondents wanted to abandon European

integration in favor of closer relations with Russia.

Nonetheless, the

ruling Georgian Dream party—founded and funded by Georgia’s richest

businessman, Bidzina Ivanishvili, and in power since 2012—is burning bridges

with its Western partners. The most conspicuous feature of this shift, although

not the only one, is the controversial “foreign influence” law, which seeks to

limit and potentially criminalize the activities of any nongovernmental

organization that receives more than 20 percent of its funding from

abroad—meaning nearly all of them. The move sparked mass protests, especially

from young people, who call it “the Russian law” because it mimics Moscow’s own

2012 “foreign agents” law and seems similarly designed to stifle civil society

and remove checks on the arbitrary exercise of power. The law is also a slap in

the face for the European Union, coming just months after Brussels formally

offered Georgia candidate status and a path toward accession to the union.

Georgian Dream’s

first priority seems to be domestic: to consolidate its own power and eliminate

opposition. The party is tightly focused on trying to win—by whatever means

possible—an unprecedented fourth term in office in Georgia’s October

parliamentary elections. Still, the sharp anti-Western turn sends friendly

messages to Russia. Another refrain of the ruling party is that it will not

allow Georgia to become a “second front” in the war in Ukraine.

Just as the

Azerbaijani leadership does, the men who run Georgia understand Moscow.

Ivanishvili, who as Georgian Dream’s kingmaker is the country’s effective

ruler, made his fortune in Russia in the 1990s and learned to win in the

ruthless business environment of that era; a coterie of people around him have

made plenty of money from Russia since the Ukraine war began. Moreover, Georgia

has opened its doors to Russian business and banking assets, and direct flights

between the two countries have resumed. The Georgian elite seems prepared to

pay the cost: one insider, former Prosecutor General Otar Partskhaladze,

is now under U.S sanctions.

If the Georgian

opposition manages to overcome its historic divisions and win this fall—no easy

task—Georgia’s pro-European trajectory will resume. But much could happen

before then. Perpetual crisis in Tbilisi now seems assured for the remainder of

this year, if not beyond. Neither side will back down easily. The government

has lost all credit with its Western partners, yet to call on Russia for

assistance would be extremely dangerous. The uncertainty adds another wild card

to any larger calculations about the strategic direction of the South Caucasus.

Losing Control

Putin recognizes the value

of the South Caucasus to Russia, but since 2022, he has had little time for it.

Moscow has no discernable institutional policy toward the region as a whole—or

for other regions beyond Ukraine. The war has accentuated the habit of highly

personalized decision-making by a leader in the Kremlin who seems uninterested

in consultation or detailed analysis.

This has left the

region’s three countries with strikingly different approaches. Azerbaijan’s

Aliyev, with his two-decade relationship with the Russian president, seems most

comfortable with Putin’s way of doing business. He can also derive confidence

from the strong personal and institutional support he gets from Turkish

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. In the case of Georgia, with which Russia has

no diplomatic relations, there are no face-to-face meetings or structured

talks. (If Georgia’s de facto leader, Ivanishvili, ever met Putin, it would

have been in the 1990s long before either man was a big political player.) Once

again, everything is highly informal and conducted by middlemen. Here, too,

business stands at the heart of a mutually beneficial relationship.

Paradoxically, the one country in the region that has long-standing formal and

institutional links to Russia—Armenia—is also keenest to break off the

relationship.

All these variables

make Russian behavior in the region, as elsewhere, highly unpredictable. Since

Azerbaijan’s capture of Nagorno-Karabakh, speculation has mounted as to what

could happen in Abkhazia, the breakaway territory bordering Russia in the northwest

corner of Georgia that has been a zone of conflict since the 1990s. Could

Russia move to annex it fully, thus securing a new naval base on the Black Sea?

Or—as some recent rumors have suggested—could a deal similar to the one with

Azerbaijan be in the offing, whereby Moscow allows Georgia to march into

Abkhazia unopposed in return for Georgia renouncing its Euro-Atlantic

ambitions? Either of these is theoretically possible—though it is also quite

likely that Putin prefers the status quo and will continue to focus on Ukraine.

At the same time, the

most obvious benefit the South Caucasus countries have derived from the

post-2022 situation—a stronger economic relationship with Russia—is unstable.

Close trading ties to Russia give Moscow dangerous leverage, especially in the

case of Armenia and Georgia, which have fewer resources and other places to

turn to for support. And if Western secondary sanctions on businesses that

trade with Russia are tightened, that would put a squeeze on South Caucasian

intermediaries.

Not everything is

going Putin’s way. Russia’s military withdrawal from Azerbaijan is a sign of

weakness. So, too, arguably, is Armenia’s pivot to the West and the Georgian

public’s mass resistance to what the opposition labels the “Russian law.” But

if Russia looks weaker in the region, the West does not look stronger. There

are significant pro-European social dynamics at work, but they face strong

competition from political and economic forces that are pulling the South

Caucasus in very different directions.

Last month, the

Georgian government awarded the tender to develop a new deep-water port on the

Black Sea at Anaklia to a controversial Chinese

company. That project used to be managed by a U.S.-led consortium. In other

words, Europe and the United States are competing for influence not just with

Russia but also with other powers, as well. Nothing can be taken for granted in

a region that is as volatile as it has ever been.

For updates click hompage here