By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

What Gazans Think

Since Hamas’s

atrocious attacks on October 7 left more than 1,400 Israelis dead in a single

day, Israel’s response has exacted a heavy toll on the population of

Gaza. According to the Palestinian Ministry of Health, more than

6,000 Gazans have been killed and more than 17,000 injured in Israel’s aerial

bombardment. The casualties could quickly climb if Israel goes ahead with its

expected ground invasion. Israeli President Isaac Herzog, Prime

Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Knesset member Ariel Kallner, and other

prominent officials have called for a military campaign covering the entire Gaza

territory. Israeli missiles have already destroyed around five

percent of all

buildings in Gaza, including where Palestinians sought shelter after heeding

Israeli calls to evacuate their homes. Some of Israel’s top officials, invoking

Hamas’s success in the 2006 Palestinian parliamentary elections, have, in

effect, declared that all Gazans are part of Hamas’s terrorist infrastructure

and complicit in the group’s atrocities—and are therefore legitimate targets of

Israeli retaliation.

The argument that the

entire population of Gaza can be held responsible for Hamas’s actions is

quickly discredited when one looks at the facts. Arab Barometer, a research

network where we serve as co-principal investigators, surveyed Gaza and the

West Bank days before the Israel-Hamas war broke out. The findings,

published here for the first time, reveal that rather than supporting Hamas,

most Gazans have been frustrated with the armed group’s ineffective governance

as they endure extreme economic hardship. Most Gazans do not align themselves

with Hamas’s ideology, either. Unlike Hamas, whose goal is to destroy the

Israeli state, most survey respondents favored a two-state solution with an

independent Palestine and Israel existing side by side.

Continued violence

will not bring the future most Gazans hope for any closer. Instead of stamping

out sympathy for terrorism, past Israeli crackdowns that make life more

difficult for ordinary Gazans have increased support for Hamas. If the current

military campaign in Gaza similarly affects Palestinian public opinion, it will

further set back the cause of long-term peace.

Mounting Frustration

Arab Barometer’s

survey of the West Bank and Gaza, conducted in partnership with the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey

Research and with the

support of the National Endowment for Democracy, provides a snapshot of the views of ordinary citizens

on the eve of the latest conflict. The region's longest-running and most

comprehensive public opinion project, Arab Barometer, has run eight waves of

surveys covering 16 countries in the Middle East and North Africa since 2006.

All surveys are designed to be nationally representative; most of them

(including the latest survey in the West Bank and Gaza) are conducted in

face-to-face interviews in the respondents’ places of residence, and the

collected data is made publicly available. In each country, survey questions

measure respondents’ attitudes and values about various economic, political,

and international issues.

Our most recent

interviews were carried out between September 28 and October 8, surveying 790

respondents in the West Bank and 399 in Gaza. (Interviews in Gaza were

completed on October 6.) The survey’s findings reveal that Gazans had little

confidence in their Hamas-led government. Asked to identify the amount of trust

they had in the Hamas authorities, a plurality of respondents (44

percent) said they had no trust; “not a lot of trust” was the second most

common response, at 23 percent. Only 29 percent of Gazans expressed “a great

deal” or “quite a lot” of trust in their government. Furthermore, 72 percent

said there was a large (34 percent) or medium (38 percent) amount of corruption

in government institutions, and a minority thought the government was taking

meaningful steps to address the problem.

When asked how they

would vote if presidential elections were held in Gaza and the ballot featured

Ismail Haniyeh, the leader of Hamas, Mahmoud Abbas, the president of the

Palestinian Authority, and Marwan Barghouti, an imprisoned member of the

central committee of Fatah, the party led by Abbas, only 24 percent of

respondents said they would vote for Haniyeh. Barghouti received the largest

share of support at 32 percent and Abbas received 12 percent. Thirty percent of

respondents said they would not participate. Gazans’ opinions of the PA, which

governs the West Bank, are not much better. A slight majority (52 percent)

believe the PA burdens the Palestinian people, and 67 percent would like to see

Abbas resign. The people of Gaza are disillusioned with Hamas and the entire

Palestinian leadership.

The salience of

Gaza’s economic troubles also showed clearly in the survey results. According

to the World Bank, the poverty rate in Gaza rose from 39 percent in 2011 to 59

percent in 2021. Many Gazans have struggled to secure necessities because of

scarcity and cost. Among survey respondents, 78 percent said that food

availability was a moderate or severe problem in Gaza, whereas just five

percent said it was not a problem. A similar proportion (75 percent) reported

moderate to severe difficulty affording food even when available; only six

percent said food affordability was not a problem.

Gazan households have

felt the impact of food shortages keenly. Seventy-five percent of respondents

reported that they had run out of food and lacked the money to buy more at some

point during the previous 30 days. In a 2021 Arab Barometer survey, only 51

percent said the same. This change over just two years is alarming. Gazans have

been forced to adjust their habits to make ends meet, with 75 percent saying

they had started buying less preferred or less expensive food and 69 percent

saying they had reduced the size of their meals.

Most Gazans

attributed the lack of food to internal problems rather than to external

sanctions. Israel and Egypt have imposed a blockade on Gaza since 2005,

limiting the flow of people and goods into and out of the territory. The

strength of the blockade has varied, but it grew notably stricter after Hamas

took control of Gaza in 2007. Nevertheless, a plurality of survey respondents

(31 percent) identified government mismanagement as the primary cause of food

insecurity in Gaza, and 26 percent blamed inflation. Only 16 percent blamed

externally imposed economic sanctions. In short, Gazans were more likely to

blame their material predicament on Hamas’s leadership than on Israel’s

economic blockade. Since the time of the survey, however, this perception may have

changed. Israel cut off water, food, fuel, and electricity supplies to Gaza

following the October 7 attacks, plunging the territory into a deep

humanitarian crisis. Some international aid has entered Gaza since, but the

suffering the Palestinians have experienced has likely hardened their attitudes

in ways that could undermine long-term peace and stability.

No More Politics As Usual

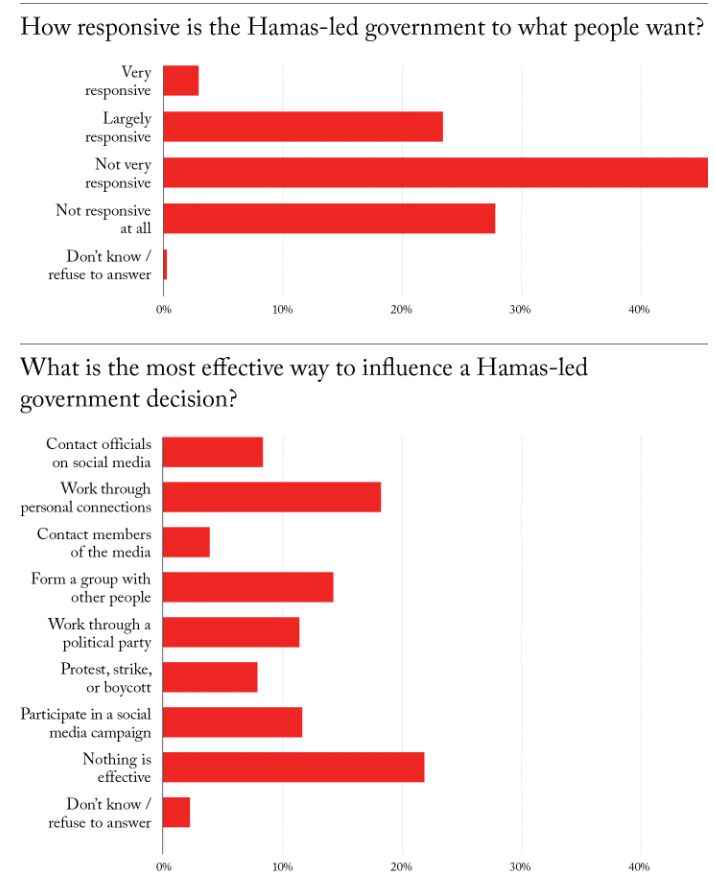

Overall, the survey

responses indicate that Gazans desire political change. In an eight-point

decline since 2021, just 26 percent said the government was very (three

percent) or largely (23 percent) responsive to the needs of the people. When

asked what is the most effective way for ordinary people to influence the

government, a plurality said, “nothing is effective.” The next most popular

answer was to use personal connections to reach a government official. Most

Gazans saw no avenue for publicly expressing their grievances with the

Hamas-led government. Only 40 percent said that freedom of expression was

guaranteed to a great or moderate extent, and 68 percent believed that the

right to participate in a peaceful protest was not protected or was protected

only to a limited extent under Hamas rule.

About half of Gazans

supported democracy; 48 percent affirmed that “democracy is always preferable

to any other kind of government.” A smaller proportion of respondents (23

percent) indicated a lack of faith in any regime, agreeing with the statement,

“For people like me, it doesn’t matter what kind of government we have.” Only

26 percent agreed that “under some circumstances, a non-democratic government

can be preferable.” (This last finding is similar to poll results in the United

States, wherein, in a 2022 survey, one in five adults aged 41 or younger

agreed with the statement, “Dictatorship could be good in certain

circumstances.”)

Given the low opinion

most Gazans hold of their government, it is unsurprising that their disapproval

extends to Hamas as a political party. Just 27 percent of respondents selected

Hamas as their preferred party, slightly less than the proportion who favored

Fatah (30 percent), the party Abbas leads and governs the West Bank. Hamas’s

popularity in Gaza has also slipped, falling from 34 percent support in the

2021 survey. There is notable demographic variation in the recent responses,

too. Thirty-three percent of adults under 30 expressed support for Hamas,

compared with 23 percent of those 30 and older. And poorer Gazans were less

likely than their wealthier counterparts to support Hamas. Among those who

cannot cover their basic expenses, just 25 percent favored the party in power.

Among those who can, the figure rose to 33 percent. The fact that the people

most affected by dire economic conditions and those who remember life before

Hamas rule were more likely to reject the party underlines the limits of

Gazans’ support for Hamas’s movement.

Visions For The Future

Leadership style is

not the only thing Gazans find objectionable about Hamas. By and large, Gazans

do not share Hamas’s goal of eliminating the state of Israel. When presented

with three possible solutions to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict (as well as

an option to choose “other”), the majority of survey respondents (54 percent)

favored the two-state solution outlined in the 1993 Oslo Accords. In this

scenario, Palestine would sit alongside the state of

Israel, their borders based on the de facto boundary that existed before the 1967 Six-Day War. The level of support for this

resolution has not changed much since 2021; in that survey, 58 percent of respondents

in Gaza selected the two-state solution.

It is surprising how

little traction alternative political arrangements had gained among Gazans before

the onset of recent hostilities, given how implausible a two-state solution now

seems. The survey presented two other options: an Israeli-Palestinian

confederation—in which both states are independent but remain deeply linked and

permit the free movement of citizens—and a single state for Jews and Arabs.

These garnered 10 percent and nine percent support, respectively.

Seventy-three percent

of Gazans favored a peaceful settlement to the Israeli-Palestinian

conflict. On the eve of Hamas’s October 7 attack, just 20 percent of

Gazans favored a military solution that could destroy the state of Israel. A

clear majority (77 percent) of those who provided this response were also

supporters of Hamas, amounting to around 15 percent of the adult population. Among

the remaining respondents who favored armed action, 13 percent reported no

political affiliation.

Gazans’ views on the

normalization of relations between Arab states and Israel, meanwhile, have been

consistently negative. Only 10 percent expressed approval of this initiative in

the most recent survey—the same percentage as in 2021. Many Gazans likely

recognize that Arab solidarity is key to securing a political arrangement that

includes an independent Palestinian state. If Arab countries were to settle

their differences with Israel without resolving the Israeli-Palestinian

conflict as a precondition for normalization, any lingering hopes for a

two-state solution would evaporate.

Before Hamas attacked

Israel, Gazans’ foreign policy views suggested alignment with specific U.S.

policy priorities and mistrust of the United States. Seventy-one percent

opposed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Thirty-seven percent wished for Gaza to develop stronger economic ties with the

United States—higher than the proportion that wanted to deepen economic

relations with Iran or Russia (32 percent in both cases). However, only 15

percent of Gazans believed that U.S. President Joe Biden’s policies had been

good or very good for the Arab world. And in the past few weeks, approval of

both Biden and the United States has undoubtedly declined, given the broad

perception in Gaza, the West Bank, and the region’s Arab countries that

Washington has come to the aid of Israel at the expense of Gaza.

A final finding—now

backed by countless media reports of Gazans’ anguish as escalating violence

forces them to flee their homes—is the strength of people’s connection to the

land on which they live. The vast majority of Gazans surveyed—69 percent—said

they have never considered leaving their homeland. This is a higher proportion

than Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Sudan, and Tunisia residents who were

asked the same question. (The most recent available data for all these

countries comes from Arab Barometer’s 2021–22 survey wave.) Gazans face a

series of challenges, from a worsening economic crisis to an unresponsive

government and a seemingly impossible path to independent statehood. Still,

they are steadfast in their desire to remain in Gaza.

Break The Cycle

The results of the

Arab Barometer survey paint a bleak picture of Gaza in the days before the

October 7 attacks. The Hamas government, unable to address citizens’ vital

concerns, had lost the public’s confidence. Few Gazans supported Hamas’s goal

of destroying the state of Israel, which divided Gaza’s leaders and its

population over the future direction of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The

vast majority of Gazans strongly favored a peaceful solution, and they yearned

for leaders who could deliver it and improve their overall quality of life. So

far, however, the policies of their government and the Israeli government have

prevented progress on both fronts.

Living conditions for

Palestinians are better in the West Bank than in Gaza, but the economic and

political situation is still grim. Nearly half of the survey respondents in the

West Bank (47 percent) reported going hungry in the last month, and just 19

percent trusted the West Bank government led by Fatah—an even lower percentage

than that of Gazans who trusted Hamas’s government. Yet governance failures

have not driven West Bank Palestinians to back Hamas. When asked which party

they feel closest to, just 17 percent of respondents in the West Bank reported

support for Hamas. The amount of support for Fatah was the same as in Gaza (30

percent). Concerning individual leaders, however, the responses of West Bank

residents reflected widespread disaffection—and particular dissatisfaction with

Abbas. In a hypothetical presidential election, Barghouti was their top choice,

as he was in Gaza, at 35 percent, while only 11 percent picked Haniyeh, the

Hamas leader, and six percent chose Abbas, the incumbent leader in the West

Bank. Nearly half of respondents—47 percent—said they would not participate.

Regarding attitudes

toward the Israeli-Palestinian peace process, support for the two-state

solution in the West Bank was slightly lower than in Gaza (49 percent versus 54

percent), and opposition to Arab-Israeli normalization was slightly higher.

Only five percent of respondents in the West Bank approved of the regional

rapprochement, compared with 10 percent of Gazans. Although the differences

were small, these relatively hardened attitudes in the West Bank were likely a

result of tensions between Palestinians and Israeli settlers and soldiers in

recent months. The survey’s finding that roughly half of Palestinians still

support the two-state solution may offer some hope for peace in the long term,

but the results do not inspire much confidence in short-term stability. The

deep unpopularity of Palestinian leadership, particularly in the West Bank,

calls into question the feasibility of reestablishing the Palestinian

Authority’s control over Gaza, which some media

outlets have suggested

as the next step in reconstruction after Israel’s military campaign against

Hamas is complete.

As Israel’s

operations in Gaza escalate, the war will take an unfathomable toll on

civilians. But even if Israel were to “level Gaza,” as some hawkish politicians in the United States

have called for, it would fail to wipe out Hamas. Our research has

shown that Israeli crackdowns in Gaza often increase support and sympathy for

Hamas among ordinary Gazans. Hamas won 44.5 percent of the Palestinian vote in

parliamentary elections in 2006. Still, support for the group plummeted after a

military conflict between Hamas and Fatah in June 2007 ended in Hamas’s

takeover of Gaza. In a poll conducted by the Palestinian Center for Policy and

Survey Research in December 2007, just 24 percent of Gazans expressed favorable

attitudes toward Hamas. Over the next few years, as Israel tightened its

blockade of Gaza and ordinary Gazans felt the effects, approval of Hamas

increased, reaching about 40 percent in 2010. Israel partially eased the

blockade the same year, and Hamas’s support in Gaza leveled off before

declining to 35 percent in 2014. In periods when Israel cracks down on Gaza,

Hamas’s hardline ideology seems to hold greater appeal for Gazans. Thus, rather

than moving the Israelis and Palestinians toward a peaceful solution, Israeli

policies that inflict pain on Gaza to root out Hamas will likely perpetuate the

cycle of violence.

To break the cycle,

the Israeli government must now exercise restraint. The Hamas-led government

may be uninterested in peace, but it is empirically wrong for Israeli political

leaders to accuse all Gazans of the same. Most Gazans are open to a permanent,

peaceful solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Yet the views of the

people who live in Gaza are still often misrepresented in public discourse,

even as surveys such as Arab Barometer consistently show how different these

narratives are from reality.

In the immediate

term, Israeli and especially U.S. leaders need to secure the safety of Gazan

civilians, 1.4 million of whom have already been displaced. The United

States should partner with the United Nations to create clear humanitarian corridors

and protected zones. Washington should contribute to the UN’s appeal for $300

million in aid to protect Palestinian civilians—a step dozens of U.S.

senators have said they will support. Finally, Israel and the

United States must recognize that the Palestinian people are essential partners

in finding a lasting political settlement, not an obstacle to that worthy goal.

If the two countries seek only military solutions, they will likely drive

Gazans into the arms of Hamas, guaranteeing renewed violence in the years

ahead.

For updates click hompage here