By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

The Secret History Of

The Glastonbury Festival

Today The Times, June

23, 2023, carries an article about Gatecrashers plotting to breach Glastonbury

festival's fences this year could if they succeed, jeopardize the event's

future, the organizers said yesterday. Unveiling an "impenetrable"

£1m security fence, the festival's founder, Michael Eavis,

urged those without tickets to stay away to safeguard the future of Europe's

most enduring music and arts festival.

Gatecrashers plotting

to breach Glastonbury festival's fences this year could, if they succeed,

jeopardize the event's future, the organizers said yesterday. The

festival's founder, Michael Eavis, urged those

without tickets to stay away to safeguard the future of Europe's most enduring

music and arts festival.

Michael

Evans

He said that two years ago, there was a massive influx

of ticketless people on the site - his dairy farm in Glastonbury, Somerset -

which caused the cancellation of last year's festival. He warned that another

breach, during the three-day event from June 28-30, could see the festival

stopped for good. Avon and Somerset police and Mendip

council say that it will not get a license if the event exceeds its limit of

105,000 people.

The Glastonbury

festival, most likely little known by attendees like Greta

Thunberg, originally was

a source of myth and mystery.

As detailed below,

the fame of Glastonbury was and for many still involves the finding of the

alleged H. Grail.

Early on, planned as

a new Bayreuth, the first performance in Glastonbury pictured below

was based on a book by 'Fiona Macleod' and intended as part of the Celtic revival.

Arthur’s Rest?

The alleged existence of a real King

Arthur has

always been confusingly conversant with the many legends the monarch is

associated with throughout Celtic mythology. A chronology of Arthur’s life was

assembled by Geoffrey of Monmouth in the Historia regum Britanniae around

1140, which pinned down sites such as Tintagel in

Cornwall and Caerleon in South Wales as being pivotal locations in his

life. Another was the Isle of Avalon, a magical backwater where Arthur’s sword

Excalibur was forged – and one of many speculated locations where the

mortally-wounded king was later buried.

One of the more

potent reasons modern Glastonbury remains one of the strongholds of Arthurian

legend is that Glastonbury

Abbey not only

claimed to be the home of Arthur’s final resting place: it claimed to have

the bones to prove it.

See below is the

'Holy Thorn' – a more recent addition – on Wearyall

Hill. Legend records that Joseph of Arimathea planted his staff here, growing

into a hawthorn that miraculously flowered twice a year. The original tree was

burned during the civil war; it was replaced a number of times.

Most modern

historians believe the entire affair was staged by the monks desperate for

interest and funds following a devastating fire ten years earlier. The evidence for this centers largely on a lead plaque found in the grave in

1191, which specifically records that the remains belonged to King Arthur and

Guinevere. This seemingly

suitably grizzled artifact was

consistent with the burial custom of a century before – but as Arthur was said

to have died around the 6thcentury, had the plaque has truly been

interred with the king and his queen at the time of the funeral, it still would

have been some 600 years ahead of its time.

Glastonbury Tor rises

above the mist. The Tor was once an island, and many 'Avalonians'

believe it to be the island upon which King Arthur was buried – and Excalibur

forged.

To some, this is

literal. Glastonbury lies on a ‘ley

line’ – part of

an implied network of impressionistic significance said to run across the land

in straight, intersecting lengths not unlike a cobweb. These are said by

believers to link or align ancient monuments, notable landscape features, and

settlements across the world on a series of invisible energy pathways. Ley

lines have been likened to the Chinese feng shui concept

of beneficial alignment and the energy associations of the Aboriginal ‘songlines’. They were first popularised

by amateur British

archaeologist Alfred Watkins in the 1924 book The Old Straight Track when he noticed that notable sacred or

prehistoric sites could be linked by straight lines on a map. The most famous

joins St Michael’s Mount and the stone circles known as The Hurlers in Cornwall, continues through Avebury in Wiltshire and over a series of stone prehistoric mounds,

churches, castles, and monuments in a line right across the base of Southern

England to Hopton on the Norfolk coast.

Willow trees at Godney near

Glastonbury, with the Levels in flood. The tor is

visible beyond.

Despite this, the

Arthurian ties to Glastonbury persist. Rather unusually, this could be thanks

to the strong religious atmosphere of the town. The Anglican aspect of

Glastonbury has a very strong Celtic connection. Arthur is regarded as Celtic

rather than Anglo- Saxon. And in Glastonbury, you have a Christian church founded before the

Roman mission to Christianise the English. And this church is key to

another of Glastonbury's impressively prestigious ancient claims

Below Stars and

the earth's rotation captured in a long exposure time-lapse above St Michael's

Tower, Glastonbury Tor. Polaris, the pole star, is the static star in the

center.

The Holy Connection And The Grail

Famously central to

Arthurian legend was the search for the Holy Grail: the cup Jesus Christ used

at the Last Supper and was said to catch his blood at the crucifixion. In this

link between Arthurian legend and Christianity, there are further links to

Glastonbury – with a story that develops whisper-like through the ages.

Entrusted with

Christ’s burial, Joseph of

Arimathea is said to have

either sent the Holy Grail back to Britain with his followers or brought it

personally as a missionary. In the latter case, he rests on the summit of Wearyall Hill, where he planted his staff – later

sprouting into a miraculously flowering hawthorn. This tree suffered

considerable persecution over the centuries: the alleged original was cut down

during the civil war, and the ceremonial tree that stood on the site was

repeatedly vandalized until being removed

altogether just last month. The

‘Glastonbury thorn’ is today regarded as a descendent of the original, and

refers to the genus Crataegus monogyna biflora – a variant of the common hawthorn that flowers

twice a year.

The Grail, meanwhile,

is said to have either been washed or buried by Joseph at the site of Chalice Well – which sits at the foot of Glastonbury Tor and

is the exponent of vivid red-flowing water said to issue at a rate that never

varies in flow or temperature. Today a wellness garden occupies the site. The

arresting hue of the water is due to the source being Chalice

water fortified with mineral salts: legend says it is reinforced with

the blood of Christ.

In an earlier

article, we pointed out that

while popular with Irish and Scottish Nationalists, the word "Celtic"

slowly implied "indigenous," and any further distinctions were

dropped. But there is another under-researched aspect to early Irish

and Scottish Nationalism, which is (as among others pointed out by Dr.

Mark Williams, Senior Lecturer in Early Modern History) its relationship to the occult. Also, in his book

about the Celtic Revival, Mark Williams points to occultists

like William Butler Yeats (in his relationship with the Golden

Dawn) and George William Russell and his relationship with

Theosophy.1

Early on, a member of

the Irish Republican Brotherhood and who served two terms as a Senator of the

Irish Free State, W. B. Yeats, as we pointed out, worked for Irish

independence. Still, he conceived of it in terms that were primarily related to his occult studies.

And Yeats hoped to gain intimate knowledge of a sacred or "hidden"

Ireland through his occult practices. He saw the magical practice as a source

of reliable information about the connections between what he used in his

literary work and the wellsprings of national and occult knowledge. To claim

this secret knowledge, he and several other students of the occult planned to

revive the Druidic mysteries, as mentioned, in a stone castle on Trinity

Island. Here Irish republican revolutionary Maud Gonne, William Sharp (wrote

under the name of Fiona Macleod) who took an interest in the La Jeune Belgique movement where he saw parallels with

Scotland’s situation, the uncle of W.B. Yeats George Pollexfen (who,

like Yeats was initiated into the Golden Dawn, Annie Horniman (Yeats persuaded

her to go to Dublin to back productions by the Irish National Theatre Society

and later opened the Abbey Theatre), Dorothea Hunter, and Liberal politician

George W. E. Russell, all worked closely with Yeats to design the Castle's rituals

and symbolism.

Yeats also consulted

with the founder of the Golden

Dawn, MacGregor Mathers.

The Story Of The Chalice Well

The father of a West

Country doctor, Dr. Goodchild, acquired a small howl of blue glass with a green

surround decorated with tiny crosses on a visit to Bordighera

in Italy in the 1890s. It was said to have been found in a cleft in a boulder

by a local peasant and seemed old. His son, some years later, had a vision

instructing him to take the howl to the "Women's Quarters at Glastonbury

Abbey," and he did so when he inherited the bowl on his father's death in

1898, concealing it in the well there. The only person he seems to have told

about this was William Sharp, the poet 'Fiona Macleod,' author of romantic

verses about the Hebrides.'' By whatever means, the secret seems to have been

passed on after Goodchild's death. The bowl was retrieved in 1906 after another

eccentric character, Wellesley Tudor Pole, had a vision in which he was given directions

to send a messenger "pure in the sight of God" to search a well at

Glastonbury, which he also saw in his vision. He sent his daughter and a

friend, and they identified the spot as Bride's Well. The glass cup was

retrieved, and it was a sensation for a brief few months.

Dom Aidan Gasquet,

the distinguished Benedictine scholar, took it to Birmingham for examination:

A. E. Waite and Annie Besant, president of the Theosophical Society, looked at

it in London. Waite was cautious and skeptical, but Wellesley Tudor Pole had

known Archdeacon Wilberforce, Canon of Westminster, for thirty years.

Wilberforce believed that Tudor Pole had always suffered from religious mania,

but he was impressed by the change in his behavior and his account of the

affair. Wilberforce presented it to the world as the Grail on 20 July 1907. The

press quickly picked it up and showed it to visiting celebrities like Mark

Twain.

The relic was returned

to the West Country and was kept at Clifton in a room known as the Oratory,

which was opened to visitors on request. Without evidence of its origin,

interest gradually faded, and the "Oratory" was closed. The Pole

family kept the cup, and is now the property of the Chalice Well Trust. It was

shown to members of the Society of Antiquaries when they visited Wells, and the

general opinion was that it was too well preserved to be ancient.

So What Happened?

Pole's life of

experiencing visions took its first lasting step forward in 1902. That year he

had a serious illness with some vision. Whether that experience or another, he

also later claimed to have vivid dreams of being a monk at Glastonbury, which

inspired a strong enough interest for him to visit there that year and had

further experiences that led to further trips "to gain inspiration"2

Ultimately a cup was

found about which there was much inquiry and news coverage. Pole and his

assistants recounted the whole affair as they knew it before a group in July

1907, including Archdeacon of Westminster Basil Wilberforce, saying, "He

may be deluded himself, but one thing is perfectly certain, that he is not

going to attempt to delude you."3 In the early 20th century, there was a

porous relationship between liberal Christianity and esoteric or spiritualist

ideas, eastern philosophies, social causes, and eastern religions.4 high-status

individuals were at this meeting to discuss the cup, Pole's, and assistants'

experiences. These 40 can be thought of as a spectrum of interests in this

milieu inside and outside mainstream Christianity when they met - some of the

leaders in that discourse of ideas, like Pole who can be summed up as a

centerpiece of a 'Celtic' network in the sense of Celtic by connotation and reputation,

though not history, and Albert Basil Wilberforce who was a leader among the

more Christian elements though with an apparent proclivity to associate with

other kinds of religiosity.

The story was

recounted for the group. In later 1904, Pole had a feeling of a pending

discovery to be made in Glastonbury that would link the founder of the

Christian faith with modern leaders of Christian thought and left word to watch

for such a discovery with the Roman Catholic College priest there. Pole was

inspired by the idea that a pre-Christian culture existed in Ireland, which had

extended to Glastonbury and Iona and was the repository of an authentic Western

mystical tradition, the true roots of spiritual life in the West.… Still, his

pursuits also blended identification with the 'mystic East,' with an interest

in Hermeticism, Theosophy,

and Spiritualism. In some respects, Tudor Pole's pursuits mirror the

activities of those promoting the 'Celtic Revival' in Ireland during this

period, though distinct alterity in their worldview is acknowledged.

In Pole's second

visit, he envisioned three maidens who would help in the "work" in

Glastonbury and had brought his sister Katherine in on successor visits there.

Then in 1905, he added two friends to the interest and trips - Allen sisters

who went in early September and another in November during the latter, of which

one had a vision of a woman's hand raising a cup out of a stream and returned.

Then Pole envisioned a specific spot at a business meeting in Bristol and sent

the Allen sisters to the particular spot the same day - they had been there a

couple of times. There, amidst some 3 feet of water and another couple of feet

of mud, they found a cup but decided it was too sacred for them to handle, so

they washed it and left it in the water. 2 October 1906, Pole was able to send

his sister on a chill rainy day to get it and brought it to their Clifton house

in Bristol. This well was the "St. Bride's Well" (a reference to

Saint Brigid of Kildare,) a kind of Holy well.5

Pole began to consult

with people about the cup and entertain the visionary experiences of others that

appeared to link with his own and led to Pole's quest. In mid-December, Pole

consulted with Annie Besant (President

of British Theosophy Society the following year) and the British Museum and

South Kensington Museum, and Swedish Princess Karadja,

who connected him with Helena Humphreys, who from then was much involved with

the quest. She felt it was a cup from the Last Supper and handed it toward

Peter, which a woman attendant kept, and then felt the cup had migrated to a

European Church in between until finally at the ruins of Glastonbury. They had

this meeting in January 1907. Pole also had felt something important about a

"Church somewhere on the Continent" as well.

Pole also consulted

with A. E. Waite, who

confirmed it had some characteristics of the Holy Grail, details of which were

linked with the legend of King Arthur in the vision of Sir Percival of it.

However, later in September, Waite disavowed the cup as the Holy Grail itself.

In the fall of 1906. and again in the spring of 1907.

Pole consulted with a medical doctor and collector, John Goodchild, who slowly

unfolded his story. Goodchild claimed to have bought it in 1887, and his father

had declared it with a sense of importance following a vision in Paris in 1897.

and the death of his father (who sent it back by courier) decided to leave it

in a well in Glastonbury. Goodchild's Paris vision indicated that his 'visitor'

had "came to you at very great danger to myself to tell you..., which may

be the first indication of ideas of threatening conditions among the

discarnate. Goodchild tried to watch out for its future discovery and even brought

a woman friend to the well hoping for it to be discovered. Goodchild had had

visionary experiences in August/September 1906 and, as a result, sent Pole a

letter with a drawing of one of his visions - a vision of a cup with five stars

- to be passed on to whomever "the pilgrims who have just been to

Glastonbury" were and was there in late September when the Allen sisters

returned after their original find of the cup. However, he did not relate his

history with the cup to them but was enthusiastic about their find. Pole and

his sister visited Goodchild in late September but shared only part of the

story. Pole never found any confirming evidence of Goodchild's statements on

the cup's history. Of the origin, placing, and recovery of the cup, some

processes and timings have been associated with Celtic and mystical thought.

They may have been a paradigm by which both Pole and Goodchild may have had a

common thinking framework. But the importance observed concerning the cup was

seen amidst ideas of the matriarchal background of Ireland via Goodchild

compared to a more Arthurian context for Pole.

23 June 1907, Pole showed the cup to the Archdeacon of

Westminster. Along with reporting on the visionary experiences leading to the

finding of the cup, Pole said other visionary experiences, which he claimed as

prophecies. While awake and not through a seance, these were received

instructions: There would be definite, tangible proof connecting the cup to

Jesus.

The cup will return

to Glastonbury. The area would become a site of physical and spiritual healing

and advance the idea that it was the place of the first touch of Christianity

to the land - see Myths and Legends of Glastonbury.

Pole warned of a

Divine outpouring of the Holy Spirit in the world… and… great intelligence…

preparing channels through which this Divine power, this second coming, this

great outpouring of the Holy Ghost, shall be manifested which, conditionally,

could be a channeled by and magnify church unity and the high position of

Britain. Still, it would no longer remain the great nation it is, and the

center of the world will be transferred to a very different country, and other

agencies will be founded. And a signal event in this process and a kind of

deadline for that condition of unity was going to be in 1911 when "those

who have been watching and preparing the way for the second coming will

recognize a great teacher who will be here and will be recognized by a few in

that year. The great teacher will be a woman and recognized by those who are,

as I say, preparing the way, by a seven-pointed star that will be worn on her

forehead.…[but] not be recognized by official Christianity...

The prophecies

envisioned a rebirth of Christian unity among the islands of Great Britain and

a rival to the Roman Catholic Lourdes site. Still, if unity could not be

achieved, another situation would be found, and another country would take the

fore.

The cup became very

well-known and is still commented upon in various contexts.6

Wilberforce accepted

the cup as the Holy Grail. Pole claimed it was at one time in possession of

Jesus and provided the opportunity for a new wider religious framework in terms

of respect for geography and a breadth of ideas that later were taken up as a

theme of New Age thought. The fact that newspaper accounts validate the

seriousness of the proceedings and reception of the claim is argued to fit into

this being about a curio and a meeting of ideas, including but not dominated by

differences of ideas.

The meeting had been

meant to be quiet and private, but it was published in the newspaper a week

later. Indeed it was carried in the news internationally.

Though most soon

understood the cup to be too modern, and Wilberforce's enthusiasm for it caused

complications with his superiors, Wilberforce continued his associations and

investigations of religious connectivity. For Pole, the meeting introduced him

to a higher engagement profile with the exchange of ideas.

Pole and his sisters

and supporters began to host the cup in the upper room of his home in Bristol

and called it "the Oratory," a small chapel especially for private

worship.

In this period of

activity around the cup, various visions developed among Pole and others who

became associated with it. Leslie Moore was in South Africa in March 1907 and

had a vision news would come in late July of a remarkable find. In June, she sailed

for England and stayed with a friend, Miss Hoey,

and learned of the coverage and "find" and let Pole know of her

experiences before the end of July that she had had visions of papers that

would give an account of the cup. She envisioned what seemed to her a large

Catholic Church with a priest in red vestments when there was a loud banging on

the doors, and people became afraid. An acolyte then escaped through a tunnel

system that led to a chapel with a scroll and the cup, and then he left with

the cup along further tunnels coming out into a church ruin. She wrote to her

friend, who sent it on to Pole, and he sent a telegram asking her to visit him

in London. She, Miss Hoey, and Helena Humphreys

gathered. There Pole identified the Church as the Church of San Sophia, a part

of the Hagia Sophia complex in

Constantinople. This encounter solidified Pole's sense of a

quest.

Then The Doubt Came

Another such

discovery in Wales almost immediately challenged the Glastonbury Cup

"discovered" by Wellesley Tudor Pole. This was first discussed in a

pamphlet published in Aberystwyth by an American visitor, Ethelwyn Amery, who disguised where it was kept and

the owner's name.

The house was soon

identified as Nanteos, the home of George

Powell. Amery described how the cup had been brought from Glastonbury by seven

monks, who had escaped in the nick of time, just before the commissioners sent

by Henry VIII to dissolve the abbey. They fled above Strata Florida near

Aberystwyth, where the owners sheltered them even though the abbey had passed

into private hands. When the last monks died, the cup passed to the family

'until the Church should claim its own. In due course, Strata, Florida, came by

marriage to the Powells; the cup was not

recorded before the middle of the nineteenth century and was probably found at

the abbey during the previous hundred years. It was first seen in public in

18-8 when it was described as having marvelous healing powers. Recent

archaeological analysis has shown it to be a mater-howl made of a late

medieval date. It is a valuable but by no means uncommon piece; most

monasteries would have owned many of them.

How could a casual

find of such a medieval wooden vessel be transformed into a new Holy Grail? The

stork of the flight from Glastonbury has been deliberately invented using

antiquarian accounts of the dissolution of the monasteries. No historical

evidence has ever been offered to stop the cup's reputation from growing by

being repeatedly asserted. Such "invented" legends are nonetheless

extraordinarily resilient: the Nanteos stork

survived the criticism of Jessie Weston soon after it was first published, as

well as the hostility of the supporters of the Glastonbury Cup. It belongs to a

similar genre to the 'urban myths' of modern folklore, where the eyewitness is

always known to an acquaintance, and the evidence is never direct. Such stories

reveal more about the attitudes and aspirations of the society in which they

were created than any lost history. But the myth of the Nanteos Grail is alive and flourishing, as a search on

the Internet will show.

Of these five "discoveries" of the real

Grail, the most significant was that at Glastonbury, which established

Glastonbury's image as a center of ancient spiritual power. The development of

the modern traditions associated with Glastonbury is far from straightforward;

the name "Chalice Well," with its obvious overtones of the Grail,

seems to be from the eighteenth century, but many of the other stories that are

now given as long-established are probably the result of this

early-twentieth-century enthusiasm. The extent to which this spread is shown

because when the abbey itself was put up for auction by private owners in 1907,

it was nearly bought by a group of Americans who intended to found a

"school of Chivalry" there. And occultists such as the writer Dion

Fortune (Violet Firth) were attracted to Glastonbury; she was a member of one

of the successors of the original Order of the Golden Dawn and deeply involved

in theosophy. Her book Avalon of the Heart was typical of the kind of

enthusiasm that the Abbey and its surroundings now aroused. In her writings,

she invoked its Christian past and "the ancient faith of the Britons ...

its relics obliterated, its legends bent to a Christian purpose ... shadowy and

veiled." The idea of a literal Grail presence at Glastonbury resurfaces

from time to time, as in Flavia Anderson's The Ancient Secret, which

offers us a Grail, which is a crystal sphere used to generate fire, at the

center of mysteries celebrated in "the British Hades," which proves

to be none other than the famous caves at Wookey Hole.

Glastonbury was involved in the fringes of the occult

movement and the search for the physical Grail at the beginning of the

twentieth century. A different vision is that of the town as an artistic center

with a Festival for Music and Drama invoking the example of Bayreuth.

The Mystery of Glastonbury.

The festival itself

had been started by the composer Rutland Boughton, who had embarked on a cycle of

Arthurian operas; it was supported by leading lights in drama and music,

Galsworthy, Shaw, Beecham, and Elgar among them. Around the time Rudolf Steiner

built his performance temple in Dornach,

Switzerland, intended as a new Grail center, the first Glastonbury

festival was held overshadowed by the beginning of the First World War and

consisting of performances with a piano and amateur chorus rather than the

professional forces that had been envisaged. But the event has deemed a success

and was the first of a series to run until 1927; the festivals included

performances of Boughton's Arthurian operas as he finished them. In the Grail

section of the romances, Galahad owes more to his Communist politics than to

the ethereal spirituality of Glastonbury. Instead of achieving the elitist

Grail, he emerges as the champion of the oppressed.

This heady mixture of

mysticism, romantic nostalgia, Arts and Crafts liberalism, and general

eccentricity may, to the casual visitor, still seem to pervade Glastonbury

today. And from this fertile ground for the imagination, there sprang the most

massive work of fiction centered on the Grail ever to be written. John

Cowper Powys' A Glastonbury Romance outdoes the

medieval romances in sheer length. It is a vast assemblage of ideas and

observations, veering from the Rabelaisian to the numinous within a few

sentences. At the heart of the story is the immemorial Mystery of Glastonbury.

Christians had one name for this Power. The ancient heathen inhabitants had

another and quite different one. Everyone who came to this spot seemed to draw

something from it, attracted by a magnetism too powerful for anyone to resist.

Still, as different people approached, they changed its chemistry, though not

its essence, by their own identity so that upon none of them, it had the same

psychic effect ... Older than Christianity, older than the Druids, older than

the gods of Norsemen or Romans, older than the gods of the neolithic men, this

many-named Mystery had been handed down to subsequent generations by three

psychic channels; by the channel of widespread renown, by the medium of

inspired poetry, and by the channel of individual experience.

The sacred container of divine (Aryan) blood, as linked

to the history of the British Isles

The medieval feudal

royals were obsessed with family trees. Many churches show a "Jesse

Tree" on the windows, which is the family tree of Jesus. It's possible

that to claim legitimacy, they eventually came to imagine some continuity back

to Christ.

Thus the Holy Grail

during the 19th century was seen as a sacred container of divine (Aryan) blood,

as legends linked the holy history of the Bible with the British Isles. The

coronation stone at Westminster Abbey had supposedly been used by Jacob, father

of the ten tribes of Israel, and brought to the British Isles by Jeremiah the

Prophet. Local tradition held that he (his father allegedly Pandora, an

invading Pagan from the north) visited the British Isles during his biography's

"missing years."

As early as 1563,

historian John Fox stressed the "uniqueness of the English as a chosen

people' with a Church lineage stretching back to Joseph of Arimathea."

Pioneering British-Israelites

took the notion further by claiming that Britons were Hebrews.

Presenting himself as "Prince of the Hebrews and

Nephew of the Almighty," Richard Brothers promised to lead the lost

tribes of Israel back to Jerusalem. They predicted the millennium to begin in

November 1795.

The predominant idea

of the British-Israel movement was that Great Britain was the home of one or

all lost tribes of Israel, implying that the inhabitants were God's Chosen

People. Its prime source of appeal to advocates was that it sought to affirm

biblical prophecy explicitly directed to the Anglo-Saxon race and a unique

covenant with God, marking out the elite nature.

This was fuelled by new ideas of evolution and racial

superiority imbuing British society with a duty to spread a superior culture,

system, and way of life to less developed societies.

But Professor P.

Smyth of the Royal Society of Edinburgh gave an account of his measurements of

the Great Pyramid, concluding that whatever its subsequent use, it was

initially constructed as a standard for Imperial weights and measures.

According to legend,

Joseph of Arimathea founded the Abbey in Glastonbury, claimed by New Age-

John Michell during the early 1970s to be identical to "the New

Jerusalem" ground plan.

Rudolf Steiner, when

he needed money to build his temple, the first all in wood, burned down in

1923, later called Goetheanum; he suggested that

Percival's "true history" would have partly occurred near that same

property.

And Rudolf Steiner inspired his student, Walter

Johannes Stein, to write a dissertation that came to be published by R. Steiner's organization as

"The Ninth Century: World History in the Light of the Holy Grail."

W.J. Stein detailed

the historical and symbolic background behind the Grail sagas and contained a

genealogical chart Stein calls the "Grail bloodline." One side

extends into the royal house of France. Another opens down to Godfrey of

Bouillon.

Part of Stein's

thesis is that events in the lives of actual historical figures served as

models for the characters and some events in the Grail stories. According to

Stein, the people associated with this family tree were acknowledged in their

time as highly spiritual and having paranormal capacities. Yet, he also

stresses that these capacities had vanished from this family hundreds of years

ago.

An undisciplined

reader of Stein could easily confuse historical persons with symbols. Stein

intends to illustrate how the positive spiritual forces represented by the Holy

Grail are sometimes manifested in the lives and actions of people and how those

actions can affect society and events. He did not in any way state or imply

that the Holy Grail was or that it represented a bloodline. He knew very well

that was not the case.

When twisted and

distorted, these sources were used to fabricate the fiction that a special

bloodline supported by an age-old esoteric society lay behind most of the

critical political events and mysteries of French history and even the Holy

Grail.

There is one mystery:

the book that Philip of Flanders is said to have given to Chretien de Troyes.

In Witches, Druids, and King Arthur by Ronald Hutton, Robert Mathiesen’s theory claims this was a text similar to

the Sworn Book, perhaps already embedded in the form of a Latin allegorical

poem.

The Sworn Book is

written by a (pseudo) Honorius of Thebes. It invokes Solomon as one of its principal

patrons and belongs to the books where magic becomes an extension of Christian

practice.

In the first account

of the Grail story, Perceval's interview with the hermit in Chretien's Story of

the Grail, the hermit whispered a prayer in his ear that contained many of the

names of Our Lord, including the secret one. The "secret names" of

Our Lord is a highly unusual idea, certainly at the end of the twelfth century.

Chretien, whose name

means "Christian" and might perhaps be a nom de plume, realized that

this knowledge could safely be presented as a romance.

It has been argued

that there is a reference to it in work written in 1247, but other scholars believe

it to be as late as the mid-fourteenth century, which would date it later as

Chretien de Troyes "Romance. Of the Grail." The Jewish Kabbalah, from

which the names in The Sworn Book are partly drawn and from which the idea of

the multiple names of God and their power is derived, was not accessible in the

West until the late thirteenth century. While it is possible that Chretien and

"Honorius of Thebes" might both have known of it direct from Jewish

sources, this would be quite exceptional. The dating further undermines

Robert Mathiesen’s new argument described

in Witches, Druids, and King Arthur by Ronald Hutton.

Others have

convincingly argued that the theme of the vision within the Grail belongs not

to ritual magic but to the perfectly orthodox circles of Cistercian mysticism.

Unten John Dee was also

one of the owners of The Sworn Book. Still, Dee's magic, rather than

ritual Catholicism, was more like the version Marcello Vicino strived

for, that of the lost word in the form of the Biblical "Adamic"

language.

But there is no one

"truth" about the Grail. We can suggest how it may have arisen and

what it may mean because the force that shaped it is not history but

imagination, the creative thought subtly built on an unfinished story and

invented the Grail. We can offer a possible account of the history of this

interplay between imagination and belief.

At the opposite

extreme, the searchers for a physical Grail see the Grail as an emblem of a

secret tradition within the Christian Church. The kernel of the idea of a

"secret"' about the Grail is, as we have seen, part of the earliest

Grail romances: but there it is a theological secret, the secret of the Mass of

the Catholic Church. In effect, that secret is the Church's way of saying that

the doctrines surrounding the Mass are too subtle for ordinary people to

understand.

But the Grail

romances can also be read "as a great attempt in the middle ages to combat

the supremacy of Rome in the history of the propagation of the doctrines of the

Church, and to substitute another authority for that of St Peter." How

real this attempt may have been being very much open to question, but it has

been argued by modern scholars that there were just such hidden or heretical

trends that relate to the Grail.

One line of argument

sees these trends as being within the Church itself. Behind the outward forms

of faith and worship centered on the Eucharist, there was a second layer of

initiation and secret knowledge, in which the Grail represented the Eucharist.

St Peter and St Paul, and the Second by St John and Joseph of Arimathea

represent the first and outward layer. In this scheme of things, Joseph, a

minor, an almost unknown figure in the Gospels, becomes the central figure in

the hidden tradition. This tradition persisted at least until the end of the

seventeenth century.

As the "secret

disciple" of Jesus and guardian of his body, Joseph is seen as the head of

this alternative tradition, the record of which was deliberately suppressed in

the Gospels. In St John's Gospel, he is said to have kept his adherence to

Christ's teachings secret 'for fear of the Jews; but this is seen as a later

addition, making the secrecy of his belief the crucial point - John is indicating

that the whole secret tradition, otherwise unrecorded, actually exists. In this

tradition, the Grail is a substitute - more direct than in the Mass - for

Christ's body. The problem is that the evidence for such a hidden cult comes

largely from two sources: the Grail romances themselves, which, as we have

seen, are not a likely means of transmitting discussions about theology (let

alone a secret and potentially highly controversial doctrine); and froth

selective reading among the huge mass of tracts on the vexed question of

transubstantiation. This version of the "secret tradition" is, at the

end of the day, only what had once been an orthodox belief overlaid with the

legendary history of Joseph of Arimathea.

A similar scheme for

a secret doctrine of the Grail brings in as evidence W'olfram's Parzival and

with it a whole host of exotic elements; here we have a 'defined doctrine,'

either contained in a book, as in Robert de Boron or explained by a master

(such as Trevrizent in Parzival).

"This doctrine concerns a Mystery present on earth, in the fullness of its

celestial power, which calls only be accessed through a path of qualification

and in danger of death." It is kept in a hidden center (the Grail castle)

and has its special liturgy.

But the presence of this

doctrine can only be explained in terms of traditional esoteric teachings,

which are self-referring and cannot be subjected to normal scientific

criticism. However, it has been argued that examining the Islamic influences

found in Wolfram reveals the sources of this tradition, which also draws on the

Jewish esoteric lore. To validate this argument, we must accept the reality

of "Kyot" as Wolfram's source.

Wolfram mentions

one Flegetanis, the name of an Arab book, Felek Thani, or the second sphere; he is associated

with the evangelist's sign of the bull, and so forth.

Any contradictory

point in Wolfram's text is put down to the fact that he is protecting "the

secret of the transmission lot the story which he was revealing against the

horrible misunderstanding of ordinary people." And so the readings and

speculations go on: the combat between Feirefiz and Parzival symbolizes

the "essential unity of Christianity and Islam (and implicitly, at least,

of Judaism)." Once the Celtic elements are brought in, the Grail becomes

the "spiritual and doctrinal " repository of the primordial

Tradition.

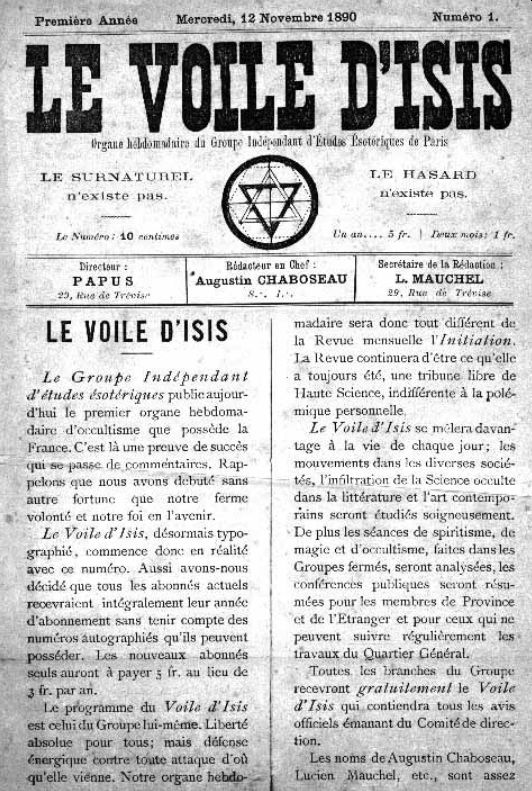

This "primordial

Tradition" leads us back to the occult revival of the 1890s and the

Theosophists. But a French writer, Rene Guenon, regarded the theosophical

Society with deep suspicion and developed this idea about the Grail in his hook

Le Roi du Monde (The King of the World).

During the same

occult revival, Peladan wrote a pamphlet

suggesting that the Grail was associated with the Cathars, a belief Rudolf

Steiner also incorporated.

On the face of it,

the Cathars are as unlikely to

be connected with the Grail as the Templars: the Grail represents

precisely those aspects of Christianity that they rejected - the Christocentric

rituals of the Church. For them, Christ was not the central figure in their

worship but merely the messenger, hearer of the new gospel of love. The

Crucifixion and Resurrection were not part of their belief. So the Grail, which

meant nothing without these two central tenets, could mean nothing to them. We

have seen how such an association is unlikely in medieval romances.

Josephin Peladan’s pamphlet

on the subject appeared in 1906, and its title was The Secret of the

Troubadours: from Perceval to Don Quixote. It was a general study of medieval

chivalric literature.

The

"secret" was no more than the continuity between medieval literature

and the age of Rabelais and Cervantes:

"Before seeking the oracle of the "dive houteillel" in Rabelais, our naive ancestor sought the

Holy Grail. In defeat, he is called Don Quixote: this is the secret of the

troubadours."

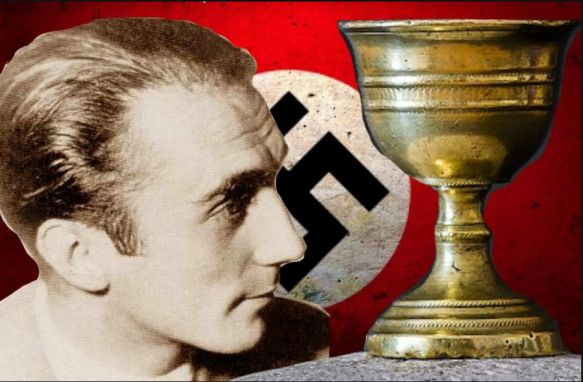

But it was this

pamphlet that came to the attention of a German scholar, Otto Rahn,

who, as part of a thesis project, researched the Cathars, also inspired

by the work of Maurice Magre, who in Magicians

and Illuminati had linked Hindu philosophy with the Cathars, whom he called

"the Buddhists of the West."

Rahn took

up the story with enthusiasm, and his book Crusade against the Grail is the

text in which the story of the Cathar Grail came to general attention.

His thesis depends on

using the sparse physical descriptions of places given by Wolfram, finding

their equivalents in the Cathar homeland. The Identification Of Munsalvaesche with Montsegur,

for instance, is based on a line in Parzival which says, "Never

was a dwelling so well fitted for defense as Munsalvaesche,"

which supposedly corresponds to "safe mountain," said to be the

meaning of the name Montsegur.

Further confirmation

of the identity of Montsegur as the Grail

castle is the idea found at the end of the Middle Ages that the Grail is the

Venusberg, home of the pagan goddess of love: Montsegur is

claimed as a pagan site.

But Rahn's next book, The Courtiers of Lucifer, recounted

his travels in the Cathar lands and elsewhere in Europe searching for the

Cathars and their philosophy and of the troubadours, who, like Peladan, lie regarded as closely connected with the

Cathars. In his travels, lie develops his thesis in terms all too familiar from

the Nazi propaganda of the period. The Cathars were said to be Aryans who

worshipped the morning star, Lucifer.

Christianity was

invented by the Jews, who tried to make men worship a Jew, Jesus of Nazareth.

The Grail was the symbol of Lucifer and was the great treasure of the Cathars

for that reason, while the Church had invented the story of the Grail as the

cup of the Last Supper to discredit the Cathar relic, which they knew to be the

true Grail.

Because Rahn was an ardent Nazi and member of the SS, stories

began to circulate that the Nazis had mounted a search for the Cathar

Grail. Rahn was supposed to have had a

double identity.

Other sources say

that members of a French right-wing society conducted a dig in the Cathar

territory in search of the runic tablets, which according to certain rumors,

were at the root of the text of Wolfram.

When local people

gathered at Montsegur on the exact day of

the Tooth anniversary of its fall, a German aircraft is said to have flown over

the ruins, tracing a Celtic cross in the sky.

But none of those present

seem to have made a formal statement to this effect; even more improbable is

the suggestion that Rosenberg was on hoard since Rosenberg devotes a bare four

or five lines to Catharism in

The Myth of the Twentieth Century.

1. Mark Williams, Ireland's Immortals: A History of

the Gods of Irish Myth, 2016, p. 313 ff.

2. Baha'i Seer - The

Extraordinary Life and Work of Wellesley Tudor Pole. Newcastle, UK: Association

of Baháʼí Studies Seminar. Retrieved 7

September 2019.pp. 9–10 ff.

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wellesley_Tudor_Pole#cite_note-8)

3. Gerry Fenge, The Two Worlds of Wellesley Tudor Pole, 2010,

pp18–19 ff. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wellesley_Tudor_Pole#cite_note-8)

4. Brendan McNamara

(2014). "The 'Celtic' Dimension of Pre-First World War Religious Discourse

in Britain: Wellesley Tudor Pole and the Glastonbury Phenomenon.

(https://jisasr.files.wordpress.com/2014/05/the-e28098celtic_-dimension-of-pre-first-world-war-religious-discourse-in-britain-wellesley-tudor-pole-and-the-glastonbury-phenomenon-pdf.pdf).p.

91 ff.

5. J. Armitage

Robinson (1926). Two Glastonbury Legends. Cambridge University Press. p. 24, ff

6. Adrian Ivakhiv (July 2004). "(Book review of) Children

of the New Age: A History of Spiritual Practices by Steven Sutcliffe."

Nova Religio. University of California Press. 8

(1): 124–129. doi:10.1525/nr.2004.8.1.124. JSTOR 10.1525/nr.2004.8.1.124.

For updates click hompage here