By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

How the War in Ukraine Could Go Nuclear

Russia is preparing

strikes on nuclear infrastructure facilities in the territory of Ukraine. Two devices

that ignited in Europe, officials say, were part of a covert operation to put

them on cargo or passenger aircraft. As the Ukrainian News Agency earlier

reported, the aggressor country Russia uses Chinese satellites to photograph

Ukrainian nuclear power plants, which may indicate preparations for strikes on

them.

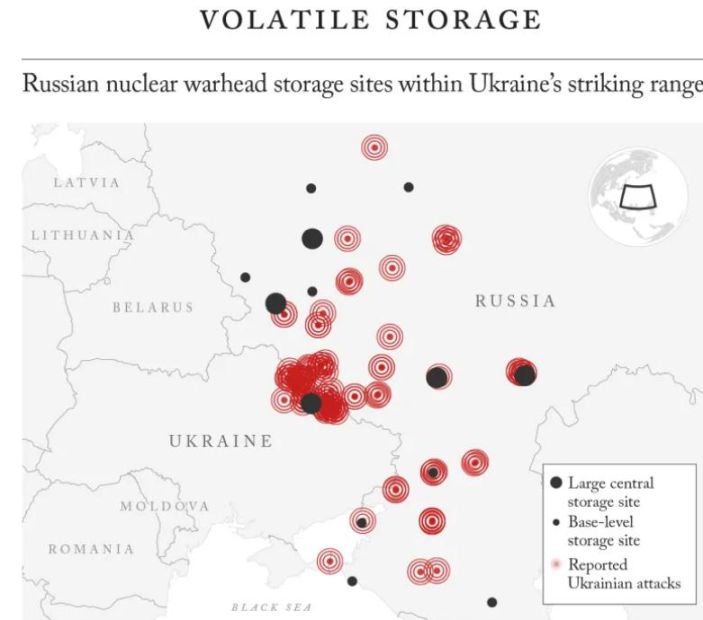

A nuclear state’s

greatest responsibility is to keep its warheads secure. Since Russia invaded

Ukraine in February 2022, it has put approximately 30 percent of its estimated

5,580 warheads in an untenably precarious position. Early in the war, concerns

that the invasion increased the danger of a nuclear detonation or accidental

explosion focused on the risk to Ukraine’s four nuclear power plants and

Russia’s threats to intentionally escalate the conflict past the nuclear

threshold. But the more Ukraine seeks to hit targets inside Russia, the clearer

it becomes that Russia’s unwillingness to adequately secure the nuclear

arsenals it has stored in its west—which are now within striking distance of

Ukrainian missiles drones, and even Ukrainian troops—poses a dire risk.

Every week, Russia

launches up to 800 guided aerial bombs and over 500 attack drones at Ukrainian

cities and energy plants. In response, Ukraine has begun launching up to

hundreds of drones daily at carefully selected Russian targets. Ukraine has

every right to defend itself in this manner, and there is no indication that

Ukrainian forces would intentionally target nuclear warhead storage sites.

Because Ukrainian drone assaults have already reached as far as Moscow,

however, it is clear that at least 14 Russian nuclear storage sites now fall

within range of its drones. At least two of those sites are less than 100 miles

from the Ukraine border, well within striking range of the more damaging

missiles Ukraine already possesses, and another five sites lie less than 200

miles from the border, close to or just beyond the range of the advanced

Western-provided missiles that Ukraine is seeking permission to use against

conventional targets in Russia.

The responsibility to

move its nuclear warheads out of the way of danger lies with the Russian

government. Russia knows that its warheads should not be positioned anywhere

near conventional military operations: after Ukraine launched its first drone

and missile attacks against Belgorod in the spring of 2023, Russia quickly

reported that its Belgorod storage site was no longer storing nuclear

warheads—acknowledging that warheads should not be stored anywhere near active

fighting. But remarkably, there have been no Russian announcements about the

status of the warheads it has at any of its other storage sites. There are

several possible reasons for Russia’s clear dereliction of duty here: Russian

President Vladimir Putin may believe that moving Russian nuclear warheads would

be a sign of weakness; senior Russian leaders may not recognize the dangers

posed to these warheads; or the Russian military may fear that the West would

misconstrue moving warheads as preparations for a nuclear attack, prompting a

pre-emptive strike by NATO.

The country that

likely has the most influence over Russia’s handling of its nuclear arsenal is

China. In September, Beijing became coordinator of the Nuclear Nonproliferation

Treaty’s P5 process, a forum of the five original nuclear weapons states—China,

France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States—designed so those

countries could jointly discuss their responsibilities. In this capacity, the

Chinese leadership can—and must—lead a collective effort to persuade Russia to

secure its vulnerable warheads, drawing on its own expanding bilateral

relationship with Moscow. If China does not push for this, the risk that

Russian nuclear sites become entangled in its war on Ukraine will only continue

to grow, with potentially catastrophic consequences both for Russia and for the

rest of the world. The possibility that a Ukrainian drone or missile will

strike a warhead and create an explosion that distributes fissile material is

already a major risk. But it is not the only one. Even more dangerous is the possibility

that a Ukrainian missile strike or territorial takeover could throw a storage

site into operational chaos, allowing rogue actors to seize its nuclear

warheads—or inadvertently prompt Russian nuclear escalation.

Warhead Games

In 1991, as the collapse of the Soviet Union

appeared imminent, the U.S. Congress established the Cooperative Threat

Reduction (CTR) program, which aimed to help Russia secure the vast Soviet

nuclear arsenal of approximately 30,000 nuclear warheads that it inherited.

Because these storage sites were no longer overseen by the Soviet police state,

their locations were no longer secret, they had little or no security

equipment, and their guards were not getting paid. With the CTR’s assistance,

Russia reduced its number of warheads and consolidated its arsenal within 42

existing storage facilities that were equipped with modern security features.

The warheads were secured at three kinds of sites: 12 large central locations

that housed hundreds of strategic and nonstrategic warheads; 30 smaller storage

facilities adjacent to military bases, which stored dozens of warheads that

could be fitted to the missiles, submarines, ships, or aircraft at the bases;

and three rail transfer points where warheads can be transferred to and from

trains to trucks. Russian warheads are frequently moved for maintenance and

safety checks, so these transfer points almost always have warheads at them—and

these rail transfer points are where the warheads are most vulnerable because

they are not in secure bunkers and are protected only by the trucks’ and rail

cars’ reinforced exteriors.

In the immediate

aftermath of the Cold War, most experts viewed the primary threat to Russia’s

nuclear stockpiles to be a potential terrorist attack—which could even be

carried out by up to 12 assailants—rather than armed conflict with another

well-armed state. Over 30 years of leading the CTR’s bilateral effort to secure

Russia’s warheads.

Security upgrades had been installed at all the warhead storage sites and rail

transfer points. Every storage site was provided with three layers of security

fencing, microwave and fence disturbance sensors, lights, video cameras, new

security gates, and a fully equipped security control building.

But these upgrades

were not designed to protect the warheads from attacks by a well-armed military

force—and they cannot do so. When Russia initiated its full-scale invasion of

Ukraine, it brought a conventional war near areas where hundreds of nuclear warheads

are stored. Russia’s Belgorod central storage site, which may have stored

hundreds of nuclear warheads, is located less than 30 miles from the Ukrainian

border north of the city of Kharkiv, where Russia instigated heavy fighting. It

is also just south of the Kursk region, where Ukrainian forces launched a major

incursion into Russia in August and where fighting continues now. Russia

reported that it removed all the warheads from this site, but it is not clear

if that was done before or after the fighting began. Moving nuclear warheads

during a conventional war is extremely dangerous behavior and would demonstrate

that Russia is no longer a conscientious nuclear power. The warheads could have

been struck accidentally by drones or missiles—or deliberately attacked or

stolen.

The major Voronezh

storage site, although it is farther east, is still less than 190 miles from the

Ukrainian border. Already, there have been multiple drone attacks less than 100

miles from it.

Russia has also

breached a sacred tenet of nuclear security by launching attacks against

Ukraine from military bases that store nuclear warheads, thus making those

bases a legitimate target for counteroffensives. Since March 2022, for

instance, Russia has been using the Engels-2 air base 500 miles southeast of

Moscow to launch Kinzhal missile attacks on Ukraine.

Kinzhal missiles are dual-capable, meaning they can carry nuclear warheads, and

there are probably dozens of nuclear warheads stored less than four miles from

the Engels-2 base’s main airfields. Ukraine has allegedly repeatedly attacked

this air base with drones, including as recently as mid-September. Russia is

believed to store dozens of nuclear warheads for short-range aircraft at the Yeysk air base, an installation directly across the Sea of

Azov from Mariupol. Dozens more may be stored at Morozovsk,

another aircraft base less than 100 miles from Luhansk, where Russian forces

are fighting off Ukrainian troops to try to recapture lost territory. The

longer the war continues, the more one or more of these sites risk getting

caught in crossfire—an outcome that could have devastating consequences.

Time Bomb

A strike on a storage

site would not in itself cause warheads to detonate in a nuclear explosion. But

if a warhead is not in its bunker because it is being moved for maintenance

within the storage site or at a rail transfer point, and it is hit by an armed

drone or missile, that could cause a major explosion that would release fissile

material and render a several-mile radius uninhabitable for years.

International observers might not even be able to judge how catastrophic such a

strike had been, because Russian reporting on nuclear incidents historically

cannot be trusted. And even if an attack did not directly strike a warhead, it

could damage nuclear security systems or kill guards, thus rendering the

warheads vulnerable to theft.

Nuclear warheads are

especially unsafe when they are located at Russia’s rail transfer points.

Although it is unclear whether Russia is currently moving warheads through any

of these sites, if it is doing so, then a Ukrainian drone or debris from a

bomber, Russian air defense system, or missile attack could easily hit them.

Given that Russia has an inventory of thousands of warheads, there are almost

always a handful that are being moved for maintenance. Ukraine, the United

States, NATO, and open-source satellites may not be able to differentiate

whether Russia is transporting warheads for maintenance or security—or to a

military base from which they might be launched. Imagine if the United States

or Ukraine detected a covert warhead movement and interpreted it to be part of

an intentional operation against Ukraine or a NATO country: they would have to

consider targeting that warhead shipment preemptively.

Beyond the immediate

risks, storing nuclear warheads in a war zone increases the likelihood of

escalatory actions by the Kremlin. Russia’s nuclear doctrine holds that an

attack on any element of its deterrent force justifies a nuclear response. It

is not clear whether an accidental strike on a nuclear warhead storage site

would cross a Russian nuclear redline, but Putin has recently sought to draw

attention to his country’s escalation doctrine. The fact that its nuclear

warheads are so close to Ukraine could tempt Russia to conduct a false-flag

operation on its storage sites to justify a nuclear attack.

But perhaps the

greatest danger now posed by Russia’s nuclear weapons storage sites is the one

that was originally envisioned after the Cold War’s end: that is, the danger

that warheads could be seized by a small, rogue group of fighters. Russia still

faces internal threats including terrorists, separatists, and the thousands of

former Wagner fighters now scattered across

Russia and Belarus. Its actions in Ukraine have greatly exacerbated the danger

posed by these long-standing threats.

On August 6,

Ukrainian troops entered Russian territory and captured a swath of the Kursk

region—an area that lies between two large Russian storage sites (in Bryansk

and Voronezh) housing hundreds of warheads. The concern is not that the

Ukrainian military would do something hazardous with loose nukes. But if the

Ukrainian military were to attack or drive Russian security forces away from a

storage site, rogue actors could enter the site and seize its warheads. Former

members of the Wagner paramilitary company, for instance, might wish to use

such warheads against Ukraine, or Russians fighting on Ukraine’s behalf might

wish to attack a Russian city. A single Russian actor could instigate such an

operation with or without direction from Russian authorities. And with its

military tied up in Ukraine, Russia simply may not have military forces

available to respond to an attack on a warhead storage site or convoy.

Restoring Trust

To truly safeguard

its nuclear arsenal, Russia would need to end its onslaught against Ukraine and

the increasingly complicated cross-border conflict that its invasion has

generated. But with no instant end to the war in sight, more immediate steps

must urgently be taken. In the near term, Russian nuclear warheads must be

removed from any base that is close to wartime operations and bases from which

Russia is launching conventional attacks. Thus far, Russia has failed to move

its warheads out of danger. Russia believes that its advantage in nonstrategic

nuclear weapons serves to deter Ukrainian and Western escalation against

Russia. But in truth, if Russia wants to maintain that advantage, it must end

the war or relocate the warheads to safer locations. Nuclear deterrence does

not depend on warheads being located on a country’s frontlines. In fact, a

country best maintains its deterrence if it stores its nuclear weapons well out

of harm’s way.

Russia must

immediately facilitate the safe movements of all of

its warheads located within 500 miles of the Ukraine border to storage sites

east of the Ural Mountains. China, which has become a crucial partner for

Russia since the war began, is in the best position to press Russia on this

point. It can push Russian leaders to secure their warheads during bilateral

discussions or within the P5 forum. Ultimately, China cannot view Russia as a

credible nuclear power, or partner, if Russia cannot secure its nuclear

warheads away from military operations.

The other countries

that are signatories to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty as well as the

members of the UN General Assembly can also pressure Russia. If Russia does not

agree to move its warheads after this concern is raised by the P5 and the UN, repercussions

as severe as the country’s temporary or permanent removal from the UN Security

Council are warranted. As a signatory to the NPT, China may even support such

an action: Beijing cannot afford any incident involving nuclear weapons to

occur as a result of the war in Ukraine, because that

would draw much more scrutiny to its nuclear buildup. The world must convince

Russia that it is fundamentally endangering its reputation as a responsible

nuclear power: the management of its nuclear arsenal over the past two and a

half years violates the basic responsibilities expected of nuclear states.

For updates click hompage here