By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity

Sphere Part One Of Two

Drawing on widely

accepted ideas about racial hierarchies, regional economic blocs, and economic

planning, the sphere’s advocates envisioned Asia as a “familial community” that

would free itself from European exploitation under the leadership of an

advanced Japan. Each nation would perform its economic role according to its natural

abilities, coordinated by a planning system that would ensure a share in common

prosperity for everyone.

Pan-Asianism

The Opium War of 1839–1842 was a watershed

in the history of Asian–European encounters. The British victory led to the

recognition, throughout East Asia, of Europe as a common threat. At that time,

intellectuals and politicians throughout the region began to consider the

questions of “Asia” and Asian solidarity. Intending to give the concept of

solidarity substance, they began exploring Asian cultural commonalities and the

common historical heritage of the continent. Scholars have pointed out that

East Asian countries had long interactions before the nineteenth century. This

took the form of an interstate system centered on China. It was this

Sinocentric system (sometimes also known as the tributary system) the Western

powers had to accommodate when they first came into contact with East Asian

states. But it was the acute sense of crisis brought about by the Chinese

defeat in the Opium War that forced Asian writers and thinkers actively to

pursue the agenda of a united Asia, an Asia with a common goal—the struggle

against Western imperialism.

The Japanese triumph in the war with

Russia in 1904–1905 was an important turning point that accelerated the spread

of pan-Asian ideas throughout the continent. Many Asians now believed that

Japan would soon assume leadership in the struggle against the tyranny of the

Western imperialist powers. Even in distant Egypt, a delighted Arab announced

the news of the Russian defeat to the Chinese revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen

(1866–1925), who was traveling by boat through the Suez Canal. “The joy of this

Arab, as a member of the great Asiatic race,” Sun recalled many years later,

“seemed to know no bounds.” However, disillusionment with Japan soon set in

when it embarked on a program of carving out its colonial empire at the expense

of other Asian nations and justified these expansionist policies with pan-Asian

rhetoric.

The Origins Of The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity

Sphere

A Japanese propaganda postcard depicting Asian people

of different ethnicities dancing with a Japanese official, 1940s, via Japan War

Art

In August 1940,

Japanese foreign minister Yōsuke Matsuoka announced on national radio the

concept of a unified East Asia free of Western colonial subjugation. This came

to be known officially as the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. It

promulgated the belief that Asia was meant for Asians and that any foreign

subjugation would no longer be accepted under the newly established Japanese

rule. Geographically, on top of mainland Japan, Manchukuo (Japan-occupied

Manchuria), and China, Japanese rule would be expected to stretch to Southeast

Asia, Eastern Siberia, and even extend to the outer regions of Australia,

India, and the Pacific

Islands.

Intuitively, most

political observers would assert that the concept resembled the United States’

Monroe Doctrine, which

opposed European colonialism in the Western hemisphere. With the same

conviction to dominate a unified area of influence, Japanese imperial rule had

long dreamt of putting the ideals of Pan-Asianism into practice. Typically

imperialistic, Pan-Asianism is characterized by the belief in the political and

economic unity of the Asian people. Although the official announcement only

came in 1940, Japanese propaganda from the 1930s had already demonstrated the

tenets of this concept.

The Greater East Asia Conference, 1943

The Greater East Asia Conference was covered in the

Shashin Shuho, a weekly Japanese photographic

journal, 1943, via the Japan Center for Asian Historical Records, National

Archives of Japan

On 5 November 1943,

the Empire of Japan hosted a high-profile international summit known

as the Greater East Asia Conference in Tokyo.

The truth is that no

Japanese American (for example, those in Hawaii) believed in this trend except

that they were subjugated.

A show of superficial

solidarity without any concrete framework for economic cooperation or

integration, the conference achieved its propagandistic aims nonetheless. A

Greater East Asia Joint Declaration was later announced, marking the members’

commitment to ensuring co-existence, co-prosperity, and liberation from Western

colonialism. While the former might be lip service, the latter was what Japan

had hoped to emphasize at the summit, that the Japanese people were the saviors

of the Asiatics, single-handedly liberating them from

Western colonial subjugation.

Asia for Asiatics: Driving

Out Western Imperialism

A Japanese propaganda map illustration depicting

Western exploitation of the Asiatics, 1942, via The

Asia Pacific Journal

As was affirmed

repeatedly during the Greater East Asian Conference, Japan’s cry for a united

East Asia hinged heavily on removing Western colonial influences from the

continent. Japan’s Vice Minister for Commerce, Etsusaburo

Shiina, portrayed the ongoing war as a moral and constructive one fought to

restore the dignity of the Asiatics. In other words,

it was a holy war led by Japan to replace the egotistical

and power-oriented blocs established previously by the Western

colonial leaders. This set of beliefs manifested in the propaganda materials

put forth by the Japanese rulers in the occupied territories. The 1942 wartime

booklet and elementary text titled Declaration for Greater East Asian

Cooperation is a prime example of such efforts.

The booklet aimed to

convey the essence of the GEACPS, featuring colorful illustrations and a

children-friendly design. This can be seen from the map above, which shows the

various instances of Western colonialism in the region. The caption translates

to Look! America, England, the Netherlands, and others have been

keeping us down with military force and doing bad things to us in Greater East

Asia. To highlight the exploitative nature of the Western colonial

experience, a lone Japanese soldier is portrayed trying to protect parts of

China from Western military incursions, juxtaposed against the hovering

caricature of the nonchalant-looking Allied leaders Churchill and Roosevelt.

A Japanese propaganda poster titled “Roosevelt, the

World Enemy No.1!”, targeted at the Filipino people in 1942 via the United

States Naval Academy

Roosevelt himself was

often the subject of ridicule in Japan’s anti-west propaganda. As with Western

propaganda dehumanizing the Japanese people in their anti-Japan posters and

leaflets, the Japanese often portrayed Western leaders as hairy and demonic

looking. In one of the propaganda posters targeted at the Filipino people,

Roosevelt was depicted as World Enemy No.1, the sole cause of wartime

suffering. A clear-cut call to action or rally call would be emphasized in most

of these prints. This was usually in the form of galvanizing the local people

to join Japan to make reprisal on [their] common enemy.

Poster for Dawn of Freedom (1944), 1944, via IMDB

Besides print media,

films were also widely used to stoke anti-west sentiments to promote the

GEACPS. Emphasizing traditional Japanese values, filmmakers in Japan often

portrayed the Japanese as pure, righteous, and loyal folks determined to

liberate Asia from colonial oppression. Usually sponsored by the Ministry of

Army, these films were also known for featuring themes of sacrifice and seppuku, Japanese ritual suicide.

Japanese Soldiers Beating Up Women Fruit Sellers for

Trading with Prisoners by Ronald William Fordham Searle, 1942, via Imperial War

Museum, London

In furthering the

idea of the GEACPS, the Japanese proclaimed themselves as the liberators of

Asia, swearing to save their fellow Asian brothers from centuries of Western

colonial exploitation. However, within it existed an implicit, underlying

agenda that sought to differentiate the superior Japanese race (Yamato) from

the other Asiatics. A top-secret official document in

1943 titled An Investigation of Global Policy with the Yamato Race as

Nucleus revealed such tendencies.

Detailing notions of

racial supremacy, nationalism, and colonization for living space, the

3,127-page-long document reeked of the racist beliefs of Nazi Germany. Behind the so-called Asian fraternity and

brotherhood, Japan had projected to the people in the occupied territories the

master race theory that deemed the Yamato race as hereditarily superior. This

manifested in abusive and vicious acts towards the people in occupied

territories, which could range from the slapping of faces to torture and

indiscriminate killings.

A Japanese map detailing the southern resources such

as oil, tin, and rubber, 1942, via Story of Hawaii Museum

Beyond the grandeur

of the ideological struggle put forth by the Japanese, a practical concern

prevailed as part of the GEACPS, at least implicitly. Japan had long known for

its vast resources in Asia. It could feast on the once the Western colonial

rule was destroyed. In December 1941, Minister of Commerce and Industry

Nobusuke Kishi reported on the extent of resources in Southeast Asia during a

national broadcast. He detailed the abundance of iron ore, flax, and coal in

the Philippines and the rich oil, tin, and coal supplies in the Dutch East

Indies.

Malaya, the world’s

largest rubber and tin producer, prioritized Southeast Asia's conquest to

extend Japanese supremacy. In essence, the projection of the GEACPS was but a

means to allow Japan to extract these resources to fuel its war machine.

The Sobering Reality In Japan-Occupied Asia

Bloody Saturday by H.S. Wong, 1937, via South China

Morning Post

As promising and

liberating as the GEACPS sounded, the reality in Japan-occupied Asia was far

from it. Not only did Asia not prosper under Japanese leadership, but the

wartime experience was also fraught with widespread starvation, poverty, and

suffering. This was made worse by an oppressive and iron-fisted Japanese rule

intolerant of the slightest hint of opposition. With the sobering reality on

the ground, few could fully subscribe to the ideals of the GEACPS. The years of

the Japanese Occupation wrote itself into the history of Asia as one of the

darkest periods the continent had witnessed. Resembling nothing of the bright

future, the GEACPS had promised, a regime of terror unfolded in the occupied

territories, characterized by torture, mass killings, rape, famine, and

widespread suffering. Collectively, the death toll from Japan’s war crimes in

Asia ranged from 3 million to 14 million between 1937 to 1945, mainly

consisting of civilians and prisoners of war.

Exploring Different Perspectives On The Greater East

Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

A Japanese propaganda postcard that reads The Holy War

for Prospering Asia and The Shine comes from the East, the 1930s, via Japan War

Art

With the collapse of

the Empire of Japan in 1945, the GEACPS ceased to exist, or has it ever really

existed? Most scholars argued that it was, at best, an impractical concept that

was created to cloak the sinister nature of Japanese imperialism. It was merely

a justification for Japan to exert full political domination over Asia and

exploit the resource-rich continent. Revisionist arguments, however, leaned

closer to Imperial Japan’s idea of a holy war fought to

liberate Asians from Western colonial subjugation. Though unpopular with

academics, the revisionist school of thought found favor with right-wing

politicians who propagated a liberal (mostly subjective) historical view

or jiyushugi shikan.

A select group of

scholars also took a step back to look at the bigger picture in the context of

the GEACPS. Containing elements of fascism, Japanism, and Neo-Confucianism, the

GEACPS reflected Pan-Asianism, which fundamentally motivated Japan to wage a

war of such scale. Finally, another emerging view suggests that the GEACPS was

a political dream for Japan to impose its new order. Still, the realization of

this dream was hampered by the reality of Japan’s defeat.

While various views

exist on the GEACPS, the reality on the ground has doomed it to oblivion. At

its core, the GEACPS was a spectacular failure, no matter how sincere or

sinister its motivations might or could have been at various points during the

war. As historian Jeremy Yellen puts it, the GEACPS is a contested,

negotiated process of envisioning the future during total war. Vague and

constantly in flux, the GEACPS was a victim of the shifting wartime circumstances

and came to be what Yellen deemed Japan’s failed process to represent their

envisioned future.

Pan-Asianianism

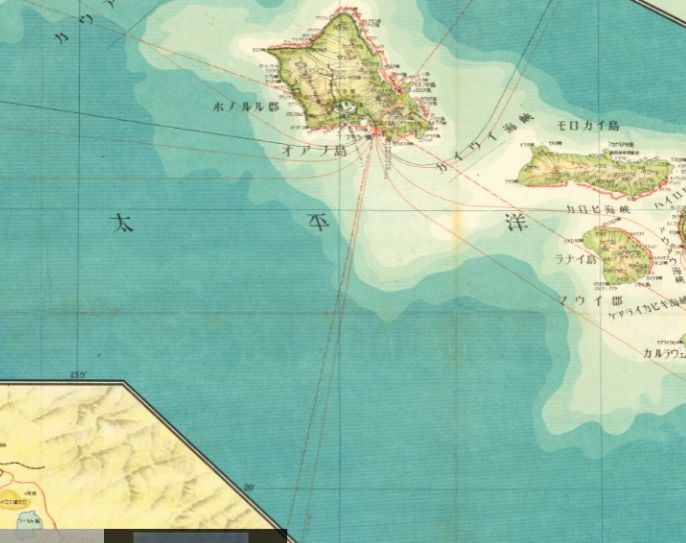

Rare 1943 Japanese

World War II map of Hawaii from the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere

series.

The map shows the

Hawaiian Islands with an inset of Honolulu and Pearl Harbor and another

detailing the outer/minor Islands.

Flight and shipping

routes appear in red. Including the map in the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity

Sphere series demonstrates the Japanese designs to take over the island.

This map was issued

as part of a 20-map series known as the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere

(大東亜共栄圏). It was an imperial concept created and promulgated for

occupied Asian populations during 1930-45 by the Empire of Japan. Hachirō Arita

announced the idea on June 29, 1940.

Pan-Asianianism was intended

as a self-sufficient 'bloc of Asian nations led by the Japanese and free of

Western powers.' It covered Southeast Asia, Eastern China, Manchuria, Japan,

the East India Islands, and parts of Oceania. The idea promoted the cultural

and economic unity of East Asians, Southeast Asians, and Oceanians. That Hawaii

is included in this map series addresses the claims the Japanese believed they

had to the archipelago.

Pan-Asian cooperation was institutionalized through

numerous pan-Asian associations founded all over Asia. It was also reflected in

pan-Asian conferences in Japan, China, and Afghanistan in the 1920s and 1930s.

These developments showed the diversity and interconnectedness of anti-Western

movements throughout Asia. A few examples will be enough to show this

phenomenon. In 1907, socialists and anarchists from China, Japan, and India

joined forces to found the Asiatic Humanitarian Brotherhood in Tokyo. In 1909

Japanese and Muslim pan-Asianists in Japan established the Ajia Gikai (Asian Congress) to promote the cause of Asian

solidarity and liberation. It was almost certainly this Ajia Gikai that a British intelligence report referred to when

it mentioned “an Oriental Association in Tokyo attended by Japanese, Filipinos,

Siamese, Indians, Koreans, and Chinese, where Count Okuma [Shigenobu,

1838–1922] once delivered an anti-American lecture”. In 1921, the Pan-Turanian Association was founded in Tokyo to rally Japanese

support for the unification of the Turks of Central Asia and their liberation

from Russian rule. The association cooperated closely with the Greater Asia

Association (Dai Ajia Kyōkai) and other Japanese

pan-Asian organizations.

The transnational character of Pan-Asianism was also

apparent in its publishing activities. Indian pan-Asianists published material

in Japan, China, the United States, and Germany; Japanese pan-Asianists

published in China, India, and the United States. Koreans, too, such as the

court noble An Kyongsu (1853–1900), published their

works in Japan. Journals with a clear pan-Asian message—the source of many of

the documents in this collection—were published in Japan, China, and Southeast

Asia.

Although such writings might be dismissed as mere

“propaganda”, there is no doubt that many Westerners were sympathetic to the

ideals of Asian solidarity and Pan-Asianism. At the center of pan-Asian

activities in Japan at the end of World War I stood the now obscure French

mystic Paul Richard (1874–1967), whose works were published in Japan, India,

and the United States and were certainly widely read in Japan.

For updates click hompage here