By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The Holy Roman Empire, the Reformation,

and the birth of the Netherlands

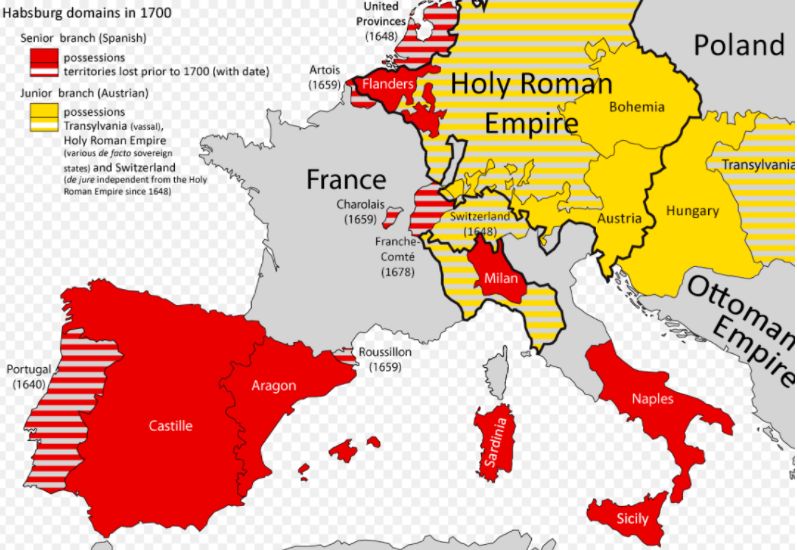

The Holy Roman Empire

was created by joining in personal union. With the imperial title the crown of

the Kingdom of Italy with the Frankish crown, notably the Kingdom of East

Francia. Soon these kingdoms would be joined by the Kingdom of Burgundy and the

Kingdom of Bohemia. By the end of the 15th century, the empire was still

composed of three major blocks. Later territorially, only the Kingdom of

Germany and Bohemia remained, with the Burgundian territories lost to France.

Voltaire observed

that the creature that called itself and still calls itself the Holy Roman

Empire is in no way holy, nor Roman, nor an empire. But in Voltaire’s time, it

was also somewhat unfair. The empire that went by the name of the Holy Roman

Empire did not aspire to be the sort of empire Constantine would have

recognized, a product of conquest and war, with centrally appointed ministers

reporting up a bureaucratic chain of command.

The empire Voltaire

described had initially been created through an agreement between the Frankish

king, Charlemagne, and Pope Leo III, in 800. Leo had refused to accept the

authority of the empress Irene, who, after deposing her son and taking power

for herself three years before, now ruled at Constantinople. After several

vicissitudes, the empire as it existed in 1500 had descended from a meeting

(called a Diet) of lords, which, in 1356, issued a charter known as the Golden

Bull. The point of the Golden Bull was to establish the terms under which a

college of seven electors, three of their bishops, would elect a new

emperor.

The terms of the

Golden Bull make it clear that imperial authority depended upon the agreement

of the essential members of the imperial aristocracy, whose own head was

negotiated with leaders in the territories they controlled. It would have been

at this point that the spirit of Constantine if it had come visiting, would

have given up in disgust. The fact that the emperor was elected, much as it

would have appalled Constantine, will be significant for understanding how the

Reformation began.

The Holy Roman

Empire’s biggest problem was not lacking holiness or Romanness

but rather the absence of a coherent bureaucratic government. As the core of

Charlemagne’s empire passed to the kings of France, the German lands to the

north remained under the control of emperors who essentially split their time

between Germany and Italy, negotiating and renegotiating their power with the

papacy as well as their sundry vassals.

In 1440, with the

election of the first member of what would become the longest-serving dynastic

group, the Habsburgs, to hold the throne as emperor, there began to be serious

efforts to make the system work better. Frederick, the second Habsburg emperor,

settled the formal relationship between the papacy and the empire through the

Concordat of Vienna in 1448. The two parties agreed that the emperor could

influence the selection of senior clerics in his territory. At the same time,

the pope would retain the right to collect taxes from Church lands and

determine matters of theological importance. The corollary of this arrangement

was that local princes began to assert greater control over Church hierarchies

in their bailiwick.

The settlement with

the Church by no means solved all of Frederick’s problems. In 1457, Frederick,

whose central European base was in Austria, tried to stabilize direct control

over Hungary and Bohemia, still a stronghold for followers of Jan Hus. His claim

was rejected. When he attempted to assert authority by force of arms, he was

defeated. He essentially withdrew, leaving power to his son Maximilian, whose

election as “king of the Romans” in 1486 marked him out as the heir

apparent.

In late Oct. 2019,

titled “For Maximilian, I, the emperor at the heart of “The Last Knight,” armor

was as much for propaganda as protection.” Titled in the exhibition “The

Last Knight: The Art, Armor, and Ambition of Maximilian I” at the Metropolitan

Museum of Art:

A better diplomat

than his father, Maximilian earned considerable goodwill by acting as a buffer

between his father and the numerous princes who opposed him. He exploited the

goodwill he’d earned by summoning an Imperial Diet at Worms in 1495. Maximilian

used this occasion to declare a

universal peace and establish a new imperial court to handle disputes

between his vassals and a new regional administration system. Additionally,

Maximilian introduced more centralized systems of taxation. Ideally, this would

supplement or replace the existing system of taxation through which vassals

were assessed contributions for imperial defense. The problem with this system

was that it meant people had to own up to what they had, while the old system

allowed them to state their worth and use it to provide troops’ levies or

contributions of cash to the imperial treasury instead of soldiers.

A more efficient tax

system was increasingly crucial because the war was getting a great deal more

expensive. The Turks had taken Constantinople, in part, because they had a

large artillery train that allowed them to batter the city walls into rubble.

Artillery required professionals who could handle the basic math necessary to

construct and fire the guns. Also, as Turkish armies ran into traditional

feudal armies, the result was routinely catastrophic from a European

perspective (it is fair to say that the early Ottoman interests in securing the

Middle East spared the empire an invasion it might not have been able to

resist). War had to professionalize, and it did so through the development of

increasingly influential bands of professional military contractors who were

now used mainly against each other as the emperor sought to enforce his

control, usually against French opposition, in northern Italy. The emperor

Maximilian spent vast sums of money on wars in Italy that began in 1494 and

lasted throughout his reign.

The princes of

Germany were just as aware of these facts as was the emperor. They rapidly shed

his preferred system of taxation for the older contribution system. If they

were to remain factors in the brave new world of military contracting, they

needed to husband their resources.

The fact the powerful

needed money created problems for the poor. Throughout southern Germany,

peasants found that access to what had previously been common land was being

restricted. They were prevented from gathering firewood, that new services were

demanded, and that new regulations were being imposed upon them. The bitterness

engendered by these circumstances reached a boiling point when the Church

discovered that it needed even more money for its purposes in the decades after

1500 and sought to suck that money out of Germany for use in its Italian

heartland.

As we approach the

fatal year 1517, the year Martin Luther would post the ninety-five theses that

sparked the Reformation, there are three characteristics of the Holy Roman

Empire to bear in mind:

1. Power had to be negotiated between the emperor and his

subjects.

2. Princes had a say in the religious organization of

their territories.

3. Money was in short supply for everyone.

The Reformation and the city of Antwerp

The Church Martin Luther

would challenge asserted its power through its control of two ways of reckoning

time. One way was cyclical, featuring a calendar based on annual festivals

celebrating the life and ministry of Christ. The other was linear, based on

sacraments that defined a person’s relationship with God at various points

during their life.

Martin Luther was a

complex man. He had a bad temper and was exceptionally confident in his

convictions. He was also possessed of unusual energy and courage.

Yet, the spread of

print books soon gave rise to a new phenomenon as the fifteenth century turned

into the sixteenth: the public intellectual. For the better part of the

previous century, a small group of dedicated scholars, calling themselves

humanists, had been recovering classical texts and, using their newfound

knowledge of the past, had started to shape intellectual discourse. The most

influential of these figures in the early fifteenth century was Poggio Bracciolini and Lorenzo Valla. Poggio took it upon himself

to “rescue” copies of classical texts buried in monasteries of southern Germany

and France, having new copies made. He asserted that the study of human letters

was a new area of learning. Valla took a different view, whose accomplishments

included a Latin translation of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War.

He believed humanistic studies should be used to correct errors in the

Christian tradition. One example was a stunning demonstration that a document

known as the Donation of Constantine, which recorded Constantine’s proclamation

of the pope as the leader of the Church, was an eighth-century fake.

Despite their

disagreements and ecclesiastical connections, Poggio and Valla showed that

intellectual life need not depend on the Church. With the newfound taste in

books that could guide life, new opportunities opened up for a new generation

of intellectuals. Chief among these men was Desiderius Erasmus, who was

unquestionably Europe’s most famous intellectual by the first decade of the

sixteenth century. It was undoubtedly Europe’s most prominent academic was

unquestionably Europe’s most famous intellectual the sixteenth century, the

city of Antwerp-in books and in cloth. It was also—as were all the lands that

now form Belgium, Holland, and Luxembourg, a part of Charles V’s empire. Once

the possession of the dukes of Burgundy, these lands had passed into the Holy

Roman Empire after the death of the last duke, Charles the Bold, in 1477.

Charles the Bold in

about 1460, wearing the collar of the Order of the Golden Fleece, painted by

Rogier van der Weyden:

In 1363, Philipp von

Valois founded the House of Burgundy as a sideline of the French royal family

of the Valois. This House of Burgundy relied on extensive territorial

expansion, which led to an intermediate empire between France and the Holy

Roman Empire, the southern part of which was the old Duchy of Burgundy and at

times the Free County and the northern part of which was the Netherlands. After

the death of the last male duke from the House of Valois, Charles the Bold,

this rulership complex was divided in the Burgundian Wars (1477). Through the

marriage of Maximilian to the heir to Charles the Bold, Maria of Burgundy, the

House of Habsburg secured the (economic this rulership complex was divided)

most important parts of tree County.

And of course, the earliest followers of Jesus (believed the

long-promised ‘king of the Jews were Jews. The church was predominantly Jewish

until after the first major war with Rome (A.D. 66-70), and not until after the

catastrophic Bar Kokhba war (A.D. 132-135) did the Jewish church of

Jerusalem come to an end, and a Gentile bishop succeeded the Jewish bishop

there. Many centuries before the Ebionites Jewish Christians) would

finally cease as a distinct and viable denomination within Christianity.

Accordingly, for Jewish and Christian scholars today, the origins of Judaism

and Christianity constitute a complex and interesting story whose interwoven

threads should not be unraveled. Ironically, the mighty Roman Empire, which

smashed the state of Israel in a series of punishing wars (from A. D. 66-135),

was itself overrun by a messianic faith rooted in Israel’s sacred Scriptures

and its ancient belief in the God of Abraham. All of this would be put once

more on its head during the Reformation as new ways were searched for.

Pictured below is

Maria of Austria (1528-1603), the daughter of Charles, who was the wife of

Maximilian and Charles V’s mother:

The former lands of

Charles the Bold had been divided into seventeen provinces, of which seven were

north of the Rhine. Dutch was the primary language spoken in these areas,

unlike the rest of Europe, where feudal forms of governance had never taken

hold. The ten provinces south of the Rhine were Flemish. The major cities

within each region maintained “ancient privileges” conferred upon them by the

dukes of the past, as here too, feudal traditions had largely evaporated. These

provinces had more excellent traditions of self-government. Among the most

important aspects of civic government were that cities had the power to

determine who was a citizen, the autonomy of their courts, and the right to

elect their administrators. Another difference from most of Europe is that

these provinces had elective assemblies known as states. In the middle of the

fifteenth century, the dukes of Burgundy had begun to summon an assembly of all

the states, known as the States-General.

Charles V had been in

Antwerp while he prepared to take up his position as emperor and was somewhat

uncomfortable with the independence of the people he found there. Indeed, his

decision to order the mass incineration of Luther’s works, widely read in Antwerp,

may have been as much a statement about the people of Antwerp as it was a

statement about Luther, toward whom his behavior would be more restrained.

The printing presses at the Plantin Moretus in Antwerp:

Plantin himself or

his son-in-law Jan I Moretus may have been familiar

with these two presses from around 1600. They have had an eventful career and

are the oldest preserved printing presses in the world.

Thomas More was not

the only nonconformist who found a Belgian publisher. On the far side of the

North Sea, he regarded as dangerously heretical works from Antwerp. The area

itself was soon home to Tyndale and Simon Fish. Their violently

anti-establishment The Supplication of Beggars drew forth from More’s

Supplication of Souls, the work in which he laid out a grisly vision of the

torments imposed on the souls in Purgatory.

Despite Charles V’s

hostility, publishers in Antwerp continued to print Luther’s writings. The fact

hundreds of copies were burned between 1520 and 1522 shows how popular they

were. There were various reasons for this popularity. One was the humanist movement,

which had shaped and spawned greater literacy levels than elsewhere in Europe;

another was the generally greater sophistication of the region’s well-developed

urban society. Yet another was the introduction of early forms of capitalism

connected to the area’s thriving cloth trade, brewing, and bulk trading, as

well as its publishing industry. Economic change was loosening the vertical

bonds that had kept people in complete submission to their overlords. Within

this setting, persecution of pro-Lutheran publishers around Antwerp drove them

a bit further north to cities like Leiden and Amsterdam. At the same time,

persecution of individuals rounded up by the Inquisition, which Charles had

dispatched to the region, fanned the flames of discontent.

Initially, the

steadfast loyalty of the area’s administrators to Charles V prevented any

reformation along the lines of what was occurring in Germany or Switzerland.

Lutheran sympathizers learned to keep their views to themselves. The lack of a

publicly organized reform movement opened the door to extremists (chiefly

Anabaptists) shunned or persecuted in Protestant lands. By the 1530s, there was

a distinct division between crypto-reformists of a Lutheran stamp and activist

Anabaptists, whose rejection of the validity of infant baptism was generally a

feature of a wholesale rejection of societal norms, which included a

willingness to experience a hideous death for their beliefs. One hundred

thirty-nine of the one hundred sixty-one persons executed for heresy at Antwerp

between 1522 and 1565 were Anabaptists, as were fifty of the fifty-five

individuals committed at Ghent.Prior to Luther’s

translation, most Europeans encountered the Scriptures through the Latin

Vulgate translation. Two differences in how these Latin and German Bibles

translate Jesus’ words in Matthew 5:32 and 19:9 may help explain how

Anabaptists (and other Reformers) diverged with Roman Catholic

views on divorce and remarriage.

Not every Anabaptist

wanted to die a painful death. As the 1530s ended, the further one was from

Antwerp, the more likely it was that an Anabaptist could survive and behave in

less overtly antisocial ways than had the reformers of Munster. Two men, in particular,

stand out, Menno Simons and Dirk Phillips, whose more pacific form of Anabaptism

was spread through publications in Dutch. When Calvinist preachers began to

arrive in the area in the 1540s, they found that much of the population had

turned from the Catholic Church, and most people were finding ways of

concealing their true thoughts from the authorities. The literature that

accompanied their arrival stressed subordination to the will of God, the notion

that martyrdom was a supreme act of faith, and that God ordained the authority

of princes. People were not yet ready to explore the implications of ordained

the authority of princes Christian Religion, that minor officials in ancient

states, such as the tribunes in Rome, had been appointed to limit the power of

kings, and that there might be a similar power inherent to assemblies of the

three orders of society (the three orders being the clergy, nobility, and

commons). That view, which challenged the notion that God sanctified royal

power, would ultimately become Calvin’s most important intellectual legacy

blessed royal power. In the 16th century, Mechelen ruled the Low

Countries. The city fulfilled the function of the administrative capital of the

Netherlands (established by Margaret of Austria, whose statue is seen below in

the center of Mechelen).

The late 1540s and

early 1550s witnessed a newly aggressive effort to counter the reform movement.

The Catholic Church reformed itself at the Council of Trent between 1545 and

1561 and promoted a new, intellectual response through the Society of Jesus (better

known as the Jesuit order), founded in Paris in 1541 by the Spanish priest

Ignatius Loyola. On the battlefield, Charles V won a smashing victory over the

forces of the Schmalkalden League at Mühlberg in 1547. In 1553, Henry VIII’s

older daughter Mary, a devout Roman Catholic, succeeded her brother Edward VI

(a firm reformer) as ruler of England. The lesson Charles and his soon-to-be

successors, Ferdinand in the Holy Roman Empire and Philip in Spain, should have

taken away from the battle of Mühlberg was that there was no going back.

Charles found he could not exploit his victory and finally conceded the point a

year later at yet another Council of Augsburg, agreeing that Protestant princes

could continue to rule their lands until the Council of Trent finished its

work.

Below Mary

Tudor. Painted in 1554 by Anthonis Mor, who was assigned to the task by Charles

V. This painting was done while negotiations were in progress for Mary’s

marriage to Philip V of Spain:

Charles’ moderation at

Augsburg was not matched by conduct in England or the Netherlands. When she

took the English throne, Mary adopted a rigid ideological line and tried to

undo Cranmer’s reforms, which had put down deep roots in the six years of her

brother’s reign. Cranmer was but one of the numerous victims of her efforts to

restore the old Catholic ways. Rather than die at stake, many intellectuals

fled to Switzerland and elsewhere, the Netherlands included. The years of

repression, associated with the queen’s marriage to Philip II, had the effect

of linking religious reform with national identity. When Mary died in November

1558, renewed reform returned with her half-sister Elizabeth (Figure 3.6).

Indeed, Elizabeth’s religious views, always malleable according to circumstance,

were less staunchly in favor of reform than those of the advisers who pushed

the reestablishment of the national, but notably not Calvinist, Church in the

immediate aftermath of her succession. The key figures of this era were members

of the newer nobility. They tended to be as hostile to what they perceived as

socially disruptive doctrines from Geneva, such as the democratic election of

Church leaders, radical changes in the liturgy, and the notion that society’s

leaders had to act responsibly in their dealings with their social inferiors,

as they were to Catholicism. That would change, but not until the issues

dividing Protestant from Catholic had reached new levels of violence on the

continent.

The “Coronation

Portrait” of Elizabeth I, by an unknown artist, makes a point about the

legitimacy of her claim to the throne:

In 1549, Charles had

taken a significant step toward centralizing imperial authority in the former

Burgundian landstooking the “Pragmatic Sacentralizing the government of all seventeen provinces

while sating that each region would retain its ancient privileges. Just how

that was supposed to work was never made clear. The hamfisted

actions of Philip II, who succeeded as ruler of the area when the exhausted

Charles abdicated in 1556, created immediate tension.

Philip had been

excluded from any claim to the English throne by the terms of his marriage to Queen

Mary and was tied up with a war against France as his wife lay dying. Now,

operating from bases in Belgium, he won a significant victory over the French.

Unfortunately, he had not learned the lessons that had gradually dawned on his

father, who had died a few months before Mary, namely that battlefield victory

rarely led to political success and that all power had to be negotiated.

In the long run,

pretty much the only thing Philip gained from his treaty with France was an end

to the expense of fighting a war. The cost of the war had put a severe strain

on his relations with the local nobility (especially those based north of the Rhine)

who had been called upon to pay for it. Philip was somewhat suspicious of this

group, as he sensed that they were unenthusiastic about Catholicism. So it was

that when he returned to Spain, he divided the government of the region between

his half-sister Margaret (the result of an illicit affair between his father

and a palace servant many years before), who ruled over the ten southern

provinces, and William of Orange, a local notable, who was granted the seven

northern provinces. William, whose father was the duke of Nassau, a territory

in the heart of the modern Netherlands, had obtained princely status when his

uncle, prince of the region of Orange in southern France, had died in

1544.

William, also known

as William the Silent because of his ability to conceal his true thoughts from

those he dealt with, was cautiously supportive of the Calvinist tendencies

among the people in the regions under his charge. This was even though he had

been given a solid Catholic upbringing as one of the terms of his inheritance

of the state of Orange. Before his appointment in 1559, he had also been among

Philip’s favorites.

The tensions between

Margaret’s Catholic administration and the sentiments of William’s subjects and

those of other nobles led to rifts within the governing group in the years

after Philip. Simply put, Mary’s court’s inquisition into the religious beliefs

of the people of the seventeen provinces seemed an outrageous violation of the

principle that the states would retain their ancient privileges. Detesting

Antoine Perrenot de Granville (1517-1586), minister

of King Philip II of Spain, he played a significant role in the early stages of

the Netherlands’ revolt against Philip’s rule.

Margaret’s chief

minister and manager of the Inquisition, William, became increasingly outspoken

in his opposition to the active repression of reformers, which he blamed on de

Granville.

At the same time that

William was attacking de Granville, a new theme began to emerge in contemporary

literature. In 1557, for instance, Peter Dathenus

published a book entitled Christian Account of a Dispute Held within Oudenaarde. He argued, following Calvin, that while good

Christians should be subordinate even to tyrannical authority, lower secular

magistrates had a duty to resist tyrants. Five years later, Protestant

ministers gathered at Antwerp and stated that it was permissible to break

co-religionists out of jail. A year earlier, Guy de Bray, a minister at

Antwerp, while arguing that all people should obey their princes, boldly

claimed that princes should avoid persecuting people for their faith. A

contemporary, Pieter-Anastasius Pieterszoon Overd’hage de Zuttere (born 1520

in Gent, died 1604 in Leiden), stated that the government should limit itself

entirely to secular affairs. These views accorded well with those of civic

magistrates who were concerned about what they saw as wholesale violations of

their ancient privileges.

The writings of de

Bray and Zuttere articulated the

issues lying behind the bold statement that William of Orange made at a meeting

of German princes in 1564, that monarchs should not rule over the souls of

their subjects (a point that was likely just as shocking for Protestants as it

would have been for Catholics). He then joined a protest against religious

repression launched by notables of his region in 1565. Protestors maintained

their loyalty to Philip while objecting to the conduct of his officials. There

was worse to come.

In 1566–1567,

widespread rioting broke out in Antwerp and rapidly spread throughout the

region as mobs began destroying religious images in churches. There were

occasional efforts on the imperial authorities to suggest that the mass action

was carried out with such assurance that it appeared the rioters had been

appointed to their task by members of local governments. On the other side, as

in the Remonstrance written by de Bray shortly before his execution, it was

plainly stated that when the demands of conscience clashed with temporal

authority, the good Christian should follow conscience. The critical point

which distinguishes de Bray’s statement from Luther’s at Worms is that Luther

was explicitly speaking for himself, while the author of the Remonstrance was

speaking for society as a whole. Johannes Michaellam,

writing a Declaration of the Church or Community of God, went even further. He

stated that government officials who infringed on the freedom of those for

whose protection they were appointed were “traitors,” and God appointed lower

magistrates to silence evil kings. This was a very long way from the doctrine

that martyrdom was good for someone.

The gradual

coordination between theological and political thinking on the subject of

tyranny and political legitimacy was given a quick shove by the arrival of the

duke of Alva, the Spanish general whom an enraged Philip had charged with

reestablishing Catholic authority eradicating reformers. He immediately

ratcheted up the level of violence. One of the duke’s first things was set up a

local inquisition, which he called the Council of Troubles. Among the many who

were executed in the next few months were several leading nobles. A powerful

response and cry for aid, composed by Marnix van St. Aldegonde, asserted that a

prince had no right to take any action concerning his country without the

assent of the governed. According to van St. Aldegonde, the regional councils,

or states, were the true source of legitimate power, and so, a ruler needed to

govern “after a prescribed form of laws and the ordinances of the states.”

According to this emerging line of reasoning, no longer was Philip II the

victim of evil ministers. Rather, he, himself, was now the source from which

evil flowed.

William of Orange was

now summoned to appear before the Council of Troubles. With him went a man

named Jacob van Wesembeke, who enunciated with

clarity the view that legitimate government rested upon community liberties and

privileges and the authority of the states. Assisted by van Wesembeke,

William set his pen to paper, producing a series of pamphlets blaming the

current troubles on the brutality of Granville and asserting that:

You will know that by

the king’s own proper consent you are free and released from the oath and

obedience you owe him if he or others in his name infringe on the promises and

conditions on which you have accepted and received him until finally every right

has been restored.

William and his

supporters continued to write, even when his attempt to expel Alva by force of

arms failed miserably. As a result, he was confined to bases in Germany until,

in 1572, the seven northern provinces named him their governor or Sta(a)holder.

The crucial point here is that political theorists had moved away from

delegitimizing their rivals to conferring legitimacy on a leader whom they

chose.

The interplay between

the prince and regional governments continued for the next few years, with the

lead tending to come from regional governments, something that would presumably

not have been imaginable were it not for the congruence that had been achieved

between Calvinism and political practice. In 1576, William led the northern

provinces in an ultimately unsuccessful effort to assert the south. This

“Pacification of Ghent” had been sparked by a major mutiny, which had destroyed

Antwerp and temporarily incapacitated the Spanish regime in the region.

Following the failure of William’s intervention, magistrates in the seven

provinces of Holland took matters into their own hands, declaring their union.

This treaty, the Union of Utrecht, would be the first formal constitutional

document in European history. It declared that:

So those from the

Duchy of Gelderland and county of Zutphen, and those

from the counties and regions of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, and the Ommelanden between river Eems and

Sea of Lauwers have thought it advisable to ally and to unite more closely and

particularly, not to withdraw from the General Union set up at the Pacification

at Ghent, but rather to strengthen it and to protect themselves against all the

difficulties that their enemy’s practices, attacks or outrages might bring upon

them, and finally, to make clear how in such cases the provinces must behave

and can defend themselves against hostilities, as well as to avoid any further

separation of the provinces and their particular members. They further stated

that the United Provinces would work together in the future, have a common

currency, a common army, and:

Concerning the matter

of religion: Holland and Zeeland . . . may introduce . . . such regulations as

they consider proper for the peace and welfare of the provinces, towns, and

their particular members and for the preservation of all people, either secular

or clerical, their properties and rights, provided that by the Pacification of

Ghent each individual enjoys the freedom of religion and no one is persecuted

or questioned about his faith. The Union of Utrecht as a pact for mutual

defense stopped short of declaring independence from Spain. That would come two

years later, when the Dutch states, on July 21, 1581, decided to

“unanimously and deliberately” declare that Philip had forfeited “all

hereditary right to the sovereignty of these countries,” and, on the advice of

William, invited the French duke of Anjou to take charge. The French alliance

failed miserably, and the states came back to William (Figure 3.7). By the time

William fell victim to an assassin’s bullet in 1584, making him the first world

leader to be murdered by a gunman, a new nation was emerging and developing the

capacity to stand independently.

William of Orange was

painted by Adriaen Thomaz Key in 1579 when he was at the height of his power.

Notably, William is depicted in civilian clothing rather than armor:

At first glance,

William’s story looks different from those of earlier Protestant movements.

Still, Luther might have been pleased to draw a line from his assertion of

individual conscience to the statement that human communities should be based

on moral principles. The sixty years from the Diet of Worms to the Dutch

declaration of independence changed the intellectual direction of Europe. They

made it possible to imagine the creation of territorial states based upon

citizenship rights rather than dependency on lordships, on the free exchange of

ideas rather than the threat of Purgatory.

At first sight, the

Dutch achievement might seem different from the German and English

Reformations. The similarities are more significant than the differences. First

and foremost was the ideological failure of Philip’s regime; without that,

there would have been no revolt. Second, the realities of modern warfare meant

that a king had to work with his subjects to see a benefit from supporting the

costs imposed upon them. This, Philip appears to have been constitutionally

incapable of doing. Third, for all that John Calvin ran a theocratic state in

Geneva, nothing in his teaching especially enabled the creation of a new

political entity. A belief in predestination that images should be destroyed

that services should be conducted in the indigenous language, that priests

should be able to marry, and that the substances of the Eucharist were not

transubstantiated, in and of themselves were insufficient doctrines upon which

to build a state. It was William’s different belief that Calvin would have

rejected out of hand, that a state should be built upon freedom of conscience

that made the big difference. This, combined with his ability to support armies

in the field and his capacity for working with local governments, made him

successful. Without the religious reform movement, William would have remained

a Habsburg functionary. Without William, the religious reform movement in the

Netherlands would have continued to offer little more to its members than a

fast track to incineration.

Society is bound by both practice and belief.

The sixteenth-century

Reformation disrupted the centuries-old alliance between secular and religious

authority that defined Europe’s social, political, and intellectual order,

making possible the emergence of societies that admitted a diversity of religious

opinion and philosophical experiment. The effect of the Reformation was to

extend the notion of a state from a community bound by shared practice to a

society bound by both practice and belief.

There can be little

doubt that Luther would have failed in taking his stand against indulgences if

he could not have counted on support from Frederick of Saxony. Nor is it

imaginable that Cranmer and Cromwell could have built a new Church that was a

hybrid of reformist thinking and traditional episcopal governance if Henry had

not been desperate for a solution to his marital problems. But Henry’s break

with Rome was made possible because Luther had shown how papal authority could

be challenged. William of Orange’s achievement was perhaps the most astonishing

of all because he built on the passions of persecuted extremists to construct a

new state independent of what appeared to be the most significant power Europe

had seen since the end of the Roman state in the fifth century CE. The common

factor here is the government of Charles V.

As Holy Roman

emperor, Charles V is a figure who is in many ways evocative of the Roman

emperor Heraclius. Heraclius failed to recognize the weakness of his empire in

the wake of the Persian war and then proceeded to alienate many of the subjects

who returned to his sway after years of Persian rule. If he had realized that

he needed to negotiate his authority rather than impose it, the door to the

Arab conquest might not have opened. Charles’ open contempt for his German

subjects and his evident weakness in the face of the challenge of the Ottoman

state invited revolt. Like Muhammad, Luther emerged from the context of a

religious reform movement to play a crucial role in uniting opposition to the

status quo. Also, like Muhammad, he did not shape the state that emerged as a

result of his preaching, that was left to others who took his ideas in

directions that he often did not approve of. His poor relationship with Henry

VIII is a case in point.

Like Heraclius,

Charles V was a decent general, but he could not recognize that victory on the

battlefield was insufficient to ensure a political result. Heraclius and

Charles were not the only people to have this problem. The bloody course of

European history after Charles’ abdication led to even greater changes. The

principles of royal absolutism were now undermined by thinkers who would study

the classical texts of the Middle Ages to be recovered by the humanists of the

previous century. The ability to control media, the key to Luther’s initial

success, will remain a critical aspect of disruptions to come. The

dissemination of ideas beyond the reach of government censorship will be a

crucial factor in the development of new ways to analyze society and new

concepts about the nature of authority. The Reformation demonstrated once and

for all that efforts to repress modernity with the tools of medievalism.

For updates click homepage here