By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

Haitian Government Dependent On

International Power

To comprehend the depth

of the rot in Haitian politics, consider the public figures slapped with

sanctions by the U.S. and Canadian governments over the last few months because

of their corruption and connections to drug smuggling and gang violence. The

list reads like a who’s who of the politically and economically powerful in

Haiti. It includes two former Haitian presidents, Michel Martelly and Jocelerme Privert, and two former

prime ministers, Laurent Lamothe, and Jean-Henry Céant,

also on the sanctions list: two cabinet ministers, four former senators,

several leading former members of parliament, and three prominent business

figures who together own a good portion of the Haitian banking system.

Over the past decade,

the rot has spread from politics to almost every barely functional Haitian

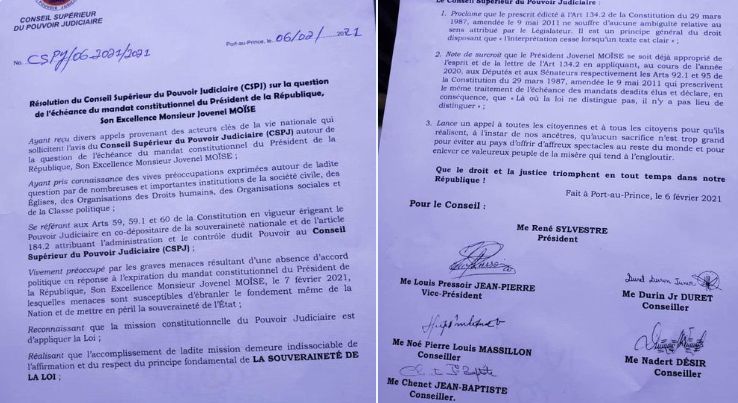

government institution. In January, a judicial oversight board refused to

recertify 30 Haitian judges because of their corruption and ethical

lapses. This group includes the judges presiding over the country’s two

highest-profile cases: the inquiry into the Petrocaribe scandal, in which $2

billion went missing from a government aid program between 2008 and 2016, and

the stalled investigation of the assassination of President Jovenel

Moïse, who was murdered in his home in July 2021.

Corruption is also deeply embedded in Haitian law enforcement. Drug traffickers

report that the Haitian police help move drugs. A handful of senior

officials and well-connected individuals—including the former head of

presidential security, a former president’s brother-in-law, and several

judges—are suspects in one of Haiti’s biggest drug trafficking

cases, which involved a shipment of over 2,000 pounds of cocaine and heroin in

2015. Government officials have been implicated in planning and providing

weapons and vehicles for gang massacres of civilians. An August report by

the Haitian government’s anticorruption unit found gross

misconduct among

town mayors, the head of the national lottery, a member of the board of

directors of the central bank, and officials at the government’s regulatory

agency, the former head of the Haitian National Police.

Criminality is

ubiquitous in Haitian officialdom. Haitian politics and government at all

levels have become so enmeshed in and dependent on graft, gunrunning, drug

smuggling, and gang violence that it is nearly impossible to disentangle them.

All this depletes the state’s capacity to provide critical social services for

Haiti’s more than 11 million people—if the current leaders had any will to do

so.

Ariel Henry, the

unelected and illegitimate acting prime minister, is deeply embedded in this

criminal system of government. His entry into politics came through several

sanctioned leaders, and his government ministers have been slapped with

sanctions, too. Meanwhile, Henry has overstayed any arguably constitutionally

legitimate term

in office—and still, many countries, including the United States, support

him.

As violence and

insecurity continue to escalate, and outsiders contemplate sending

foreign troops to Haiti, it is critical to understand how the foreign

military intervention would reinforce this relationship between crime and

politics. Haiti does not need foreign troops to solve its problems,

but it does need the United States and its partners to stop propping up a

corrupt government aligned with criminal gangs. The sanctions imposed on the

country’s former leaders are a welcome development, but they put too little

pressure on the political system to make any difference. To help Haiti move

from a criminally controlled failed state to a functional and stable democracy,

foreign governments, especially the United States and Canada, should listen to

Haitians and do everything they can to pressure Henry to step aside or go to

the negotiating table.

Rot At The Top

Henry is a product of

this corrupt political system. He previously served as interior minister

and minister of social affairs under Martelly, a popular singer who became

president in 2011. With his Parti Haïtien

Tèt Kale, Martelly laid the foundations for

a decade of government corruption, gang patronage, and drug and arms

trafficking. Martelly’s protégé and successor, Moïse,

promoted criminality with similar zeal and destroyed democratic institutions

that got in his way, such as the Supreme Court. Two days before he was

assassinated, Moïse chose Henry to become prime

minister, but Henry had not taken office when Moïse

was killed. After Moïse’s murder, foreign

diplomats quickly encouraged Henry to assume the role of prime

minister and continued to support him, even after Henry was

implicated in Moïse’s assassination.

The ongoing

international support for Henry has become increasingly difficult to

justify. Over 20 months as prime minister, Henry has presided over Haiti’s

precipitous collapse. Under his rule, gangs have ratcheted up their

violence and paralyzed the country with an entirely new form of terror for

Haiti: shutting off the public’s access to the country’s main fuel depot,

leading to hospital closures, a worsening cholera outbreak, and

widespread hunger. Rampant kidnappings, rapes, killings, and massacres are

rarely investigated, much less prosecuted. Under Henry, the judiciary has

mostly ceased to function. In January, the terms of Haiti’s last ten

remaining elected senators officially expired, leaving the country without

a single elected government official. Henry’s term in office is tied to Moïse’s, which was disputed but would have ended in any

case by February 2022. Henry has stayed in office for over a year since then,

which means his claim to power has no constitutional legitimacy.

Mass demonstrations

against Henry’s leadership have persisted for months, but Haitians have no

mechanism to oust the leader for whom they never voted. Last month, hundreds of

police officers revolted against Henry, vandalizing and shooting at his

office and his official residence in Port-au-Prince and surrounding the

airport, temporarily preventing Henry from returning from abroad, from leaving.

The United States and

Canada have encouraged Henry to start a political dialogue and create

consensus—in other words, to agree with pro-democracy civil society

leaders pushing for a democratic path forward. This broad alliance of local

organizations and institutions represents millions of Haitians. In

August 2021, leaders of the group presented their blueprint for a

transitional government that would lay the groundwork to hold democratic

elections eventually. The plan, known as the Montana Accord (after the hotel in

Port-au-Prince where it was unveiled), has close to 1,000

signatories. I helped develop this accord, believing it is the best way to

forge a path to democracy in Haiti.

But Henry has refused

to compromise with representatives of the Montana Accord. Instead, on December

21, presenting his longtime political associates as a new alliance, Henry

proposed extending his rule as prime minister by another 18 months without any

new systems of checks or balances, all in the lead-up to elections that his

government would quickly organize. He called this plan a “consensus accord,”

but it was not preceded by any serious dialogue with the main

political parties or Haitian groups working toward restoring democracy. The

blueprint offers no ideas for ensuring that elections will be peaceful,

participatory, and fair. Bewilderingly, some international officials seem

to support Henry’s bid to stay in power. In February, Brian Nichols, the U.S.

assistant secretary of state for Western Hemisphere Affairs, tweeted a quasi-endorsement of Henry’s accord, calling

the installation of a council of technical advisers “a crucial step in

restoring democratic order and improving security.” He added, “We continue

to encourage greater consensus.”

Henry’s request in October

for foreign military intervention to help combat gangs is also a move that

would help him stay in power. Although many desperate, terrorized Haitians

support this request, a military intervention would be another catastrophic

mistake. The last UN-led military mission to Haiti left a legacy of trauma

and disease. By taking the place of Haiti’s police, military, government

agencies, and civil society—without sufficiently reinforcing or supporting

reforms in any of them—UN forces weakened Haitian institutions. They

exacerbated problems in governance that led to the current crisis. Haiti’s

political leaders and government have remained dependent on foreign

governments and international institutions to an extent unseen in most of the

world. And those foreign governments and international institutions, as they

impose decisions that allow Haiti’s criminal regime to prosper, rarely

acknowledge publicly the extraordinary power they hold to make or break Haiti’s

political system.

In all likelihood,

foreign military forces would temporarily help the Haitian National Police

subdue the gangs, which would serve to prop up Henry’s failed government. This

outside support would probably keep Henry and his allies limping along so that

they could set up the kind of farcical elections that have kept criminal

politicians in office for decades in Haiti. Decent people would not risk their

lives to run for office. Few Haitians would risk their lives to vote. Votes

would no doubt be manipulated. The process might succeed in producing the

veneer of a democratically elected leadership, which would absolve the

international powers from responsibility for Haiti’s pitiful governance. But

the parliament would be composed of gang affiliates. When the foreign

forces left, the gangs would rise again.

In truth, it

is nearly impossible to move directly from a predatory state to a

democracy because predatory leaders control the levers of power and elections

and know how to manipulate them to shape outcomes. They are deeply invested in

perpetuating their power and cash flows and avoiding prosecution for their

crimes. A system this rotten cannot simply clean itself up on election day.

A Clean Break

Haitians want far

more than short-term cosmetic solutions. Through massive protests, they have

repeatedly demanded sustainable answers. That is why the road to a democratic

system must run through a representative and democratic transitional government

not affiliated with criminal elements.

Haiti has precedents

for transitional governments that successfully moved the country to viable

democratic elections. From 1957 to 1986, a family dictatorship led first by

François Duvalier and then by his son, Jean-Claude, ruled Haiti, and when their

regime fell, there was the military rule. Then, Supreme Court Judge Ertha Pascal-Trouillot was named

the provisional president of Haiti as part of a transitional government from

1990 to 1991 that paved the way for democratic elections. Jean-Bertrand

Aristide won the presidency, but a coup d’état unseated him a few months

later—and generals again governed Haiti. In 1994, Aristide returned to power

with the Clinton administration's military support. There was a stretch of democratic

government until Aristide, after being reelected, was again removed from power

following massive protests in 2004. Another Supreme Court judge, Boniface

Alexandre, assumed the role of provisional president. Alexandre’s transitional

government organized elections in 2006 that were fair and successful and

brought René Préval, who had served as president from

1996 to 2001, back for a second term.

Port-au-Prince

Well aware of these two

precedents of Supreme Court judges serving as presidents in provisional

governments, Moïse felt threatened by his

own Supreme Court and unconstitutionally fired three of the judges in February

2021. He appointed replacements, but the remaining judges refused to swear them

in. Since then, the court has been unable to hear cases because it doesn’t have

a quorum. The lack of a legitimate Supreme Court also meant that there was no

alternative ready head of state, but in early March, Henry illegally named eight

new judges to the Supreme Court.

When Moïse began acting outside Haiti’s constitution in early

2021, civil society leaders created a commission to consider taking Haiti from

a failed state to a functioning and stable democracy run by competent leaders who

prioritize Haiti’s best interests—not their own. I joined as one of 13

commissioners. As we undertook months of consultations across Haiti, it became

clear that the country needed a rupture—a clear break with the criminal

past. We saw that a carefully composed, representative, principled

transitional government was our best option to confront a deeply

entrenched, predatory system.

We hammered out the

Montana Accord, delineating a process for building an inclusive transitional

government. This government would lead the country for two years. The Montana

Accord members elected a president, expecting that person to lead the

transitional government eventually—but that is currently open to negotiations.

The founding commissioners who created Montana and the Montana Monitoring

Bureau members have pledged not to accept political positions during the

transition. The goal of the transitional period would be to strengthen

government institutions, increase security, and build trust sufficient to hold

truly participatory, free, and fair elections within two years.

Observers sometimes

mistake supporters of the Montana process for the political opposition—a

dangerous misreading that equates Montana and the Henry government as equally

legitimate rivals. Montana is a pro-democracy civil society movement working

against an antidemocratic and criminally backed power structure that includes

Haiti’s leading political parties and business interests. A broad coalition of

professionals, peasant and labor leaders, religious figures, anticorruption

activists—and yes, some politicians—have coalesced around Montana as a

democratic path forward. Many Haitians have rallied to support the Montana

process despite grave personal risks. Maintaining political consensus in Haiti

is incredibly difficult in the crucible of constant threats and violence.

Still, Montana’s leaders have made compromises over a year and a half, such as

building consensus with a powerful alliance of seven of Haiti’s political

parties.

The Role Of Outsiders

As outsiders consider

their next moves, they should stop confusing Henry’s needs with

Haiti’s. Henry seeks international forces to subdue the gangs and keep

himself in power. Haiti needs a representative transitional government to give

its people a voice and reestablish trust and institutional capacity until

secure and free elections are possible.

U.S. messaging on how

Haiti can move forward is extremely influential. U.S. officials helped install

Henry in office after Moïse’s death by

tweeting a statement asking him to form a government. More recently, the

State Department official Nichols bestowed legitimacy on Henry’s newly formed

High Transition Council by tweeting positively about it. U.S. officials should

use this power, publicly declare their concerns about Henry’s leadership, and

endorse negotiation as a way forward. After decades of influencing policy and

politics in Haiti and often creating Haiti’s rulers, the United States has

outsized power. Everyone would understand the signals that the tide was turning

and that foreign powers would no longer support an undemocratic regime. It can

happen if there is political will among U.S. officials to stop propping up

Henry’s government and bring him to the negotiating table.

But the action needed

is not just rhetorical. Other countries should cut off their massive aid for

the Haitian police until a representative transitional government is in place

to make decisions. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said Canada would not

send troops to Haiti until Haitians reached a political consensus.

It isn't easy to

understand why the international community has not yet abandoned Henry.

Diplomats often privately say that they value stability, but Henry’s

incompetent and dangerous rule has created the country's worst economic,

political, and humanitarian instability in decades. International support is

keeping Henry in power and stymieing democracy activists’ efforts to build a

more functional, more inclusive, and more stable democratic system.

Montana Accord

advocates are open to dialogue and ready to come to the table for talks; in

January, they responded positively to the Caribbean Community's offer to play a

mediating role in which Haiti is a member. Members of the Montana Accord understand

that compromises on the details of the process that the accord laid out may be

needed to come together for Haiti.

The biggest change in

policy toward Haiti in recent months has been the imposition of sanctions by

the U.S. and Canadian governments that target Haiti’s corrupt leaders—past and

present. The sanctions work to expose and isolate some of the worst, most

criminal, violent, and controlling actors in Haitian public life. They have

started to create a bit more space for democrats, including women, to operate

by speaking publicly, organizing politically, and potentially running for

office. But much more expansive sanctions, including freezing assets, are

needed to isolate a larger swath of the criminal class. Haiti does not

manufacture arms and munitions, yet the country is filled with them. The United

States can support Haiti by better controlling its ports to prevent arms from

being sent to Haiti. U.S. law enforcement can also help to vet and train

Haitian port officials to intercept the guns that feed the gangs.

For decades, Haitians

have struggled to build a democracy. Too often, Haiti’s international partners

have decided that Haitian efforts at democracy are too complicated and too

messy, and foreign countries and international agencies have responded with

intervention to manipulate electoral levers and outcomes. But those outside

efforts have failed spectacularly, and they helped create a Haitian government

as dependent on international power as it is on criminal enterprises and gang

violence. The only way to build something new is to start fresh.

For updates click hompage here