By Eric

Vandenbroeck

The Young Turks

And The Hashemite Sherif Hussein

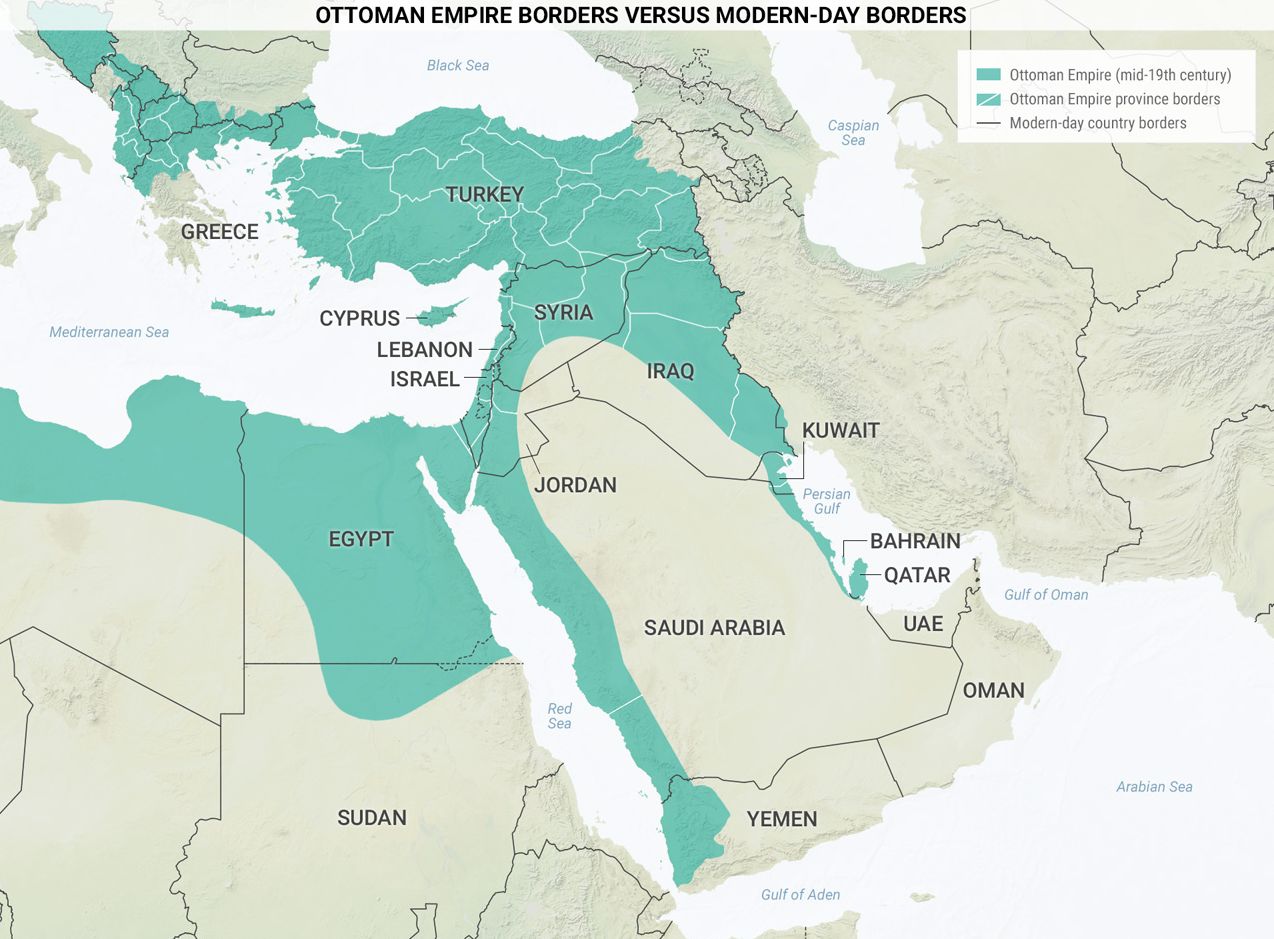

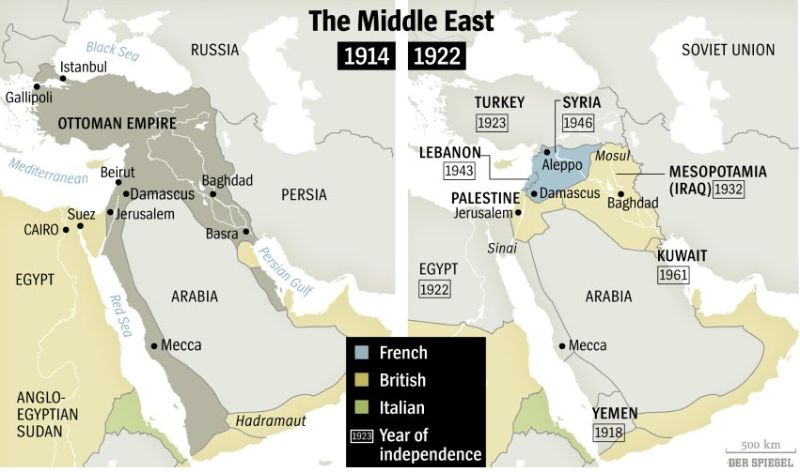

The fall of the Ottoman Empire, which ended at a stroke thirteen hundred

years of imperialism in the Middle East, was not a necessary, let alone an

inevitable, consequence of World War I. It was a self-inflicted disaster by a

shortsighted leadership blinded by imperialist ambitions. Had the Ottomans

heeded the Entente's repeated pleas for neutrality, their empire would most

likely have weathered the storm. However, they did not, and this blunder led to

the destruction of the Ottoman Empire by the British army and the creation of

the new Middle Eastern state system on its ruins. Even this momentous

development was not inevitable, and its main impetus came not from the great

powers but from a local imperial aspirant: Hussein ibn Ali of the Hashemite

family.

Following the Ottoman declaration of war, the Caliphate in

Constantinople duly declared jihad on 14 November 1914, invoking believers

throughout the Muslim world to fight Britain, France, Russia, Serbia, and

Montenegro as enemies of Islam.

It was the British who felt most vulnerable. A hundred million out of

the world's 270 million Muslims lived in the British Empire and the threat from

a panIslamic movement was one of those

simple and emotive ideas which touched a raw nerve of imperial insecurity.

The British needed help. Their advance north of Basra had recently been

repulsed, the Gallipoli campaign was in trouble, while reports suggested that

German plans for a jihad might be making serious headway. For some time there

was the thought that the Hashemite Sherif Hussein of Mecca might be a

potentially biddable proxy for the spread of British influence in the Middle

East.

The Sherif exemplified the complexity among Arabs. Before the

war, Hussein had been detained in Istanbul under the caliph, Sultan Abdul Hamid

II, who hastily conferred to him the title of emir of Mecca and Medina in the

Hejaz to prevent the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) from appointing its

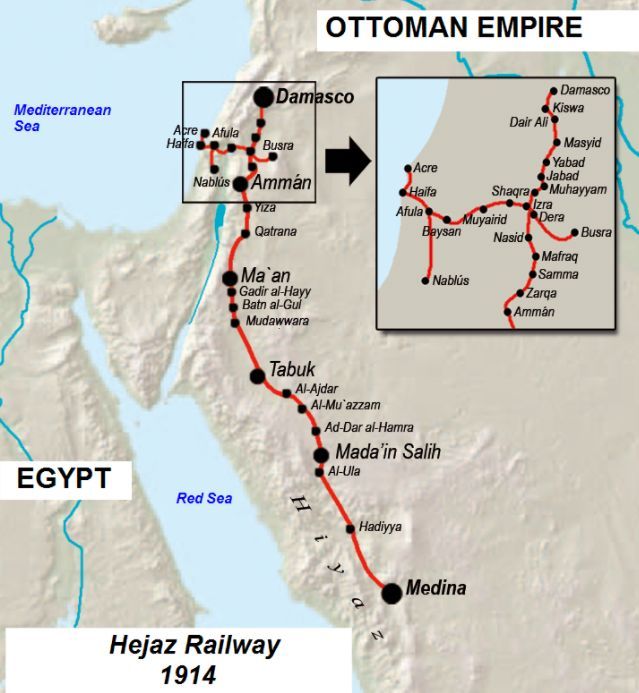

crony. In 1909 the sultan was overthrown, and Istanbul’s relationship with

the Sherif deteriorated. The revolutionary triumvirate was eager to

assert political control over the Hejaz and extend the rail links into the

Emirate, largely to be able to deploy troops more rapidly there if required.

The Sherif opposed the changes, ostensible to protect the incomes of

camel rovers who carried the pilgrims to the holy places, but his motives were

revealed in a secret meeting in the spring of 1914 between his son, Abdullah,

and the British Consul General of Egypt, Lord Kitchener and his secretary,

Ronald Storrs. The sheriff and his sons, while eager to resist Istanbul, by

force if necessary, needed British intervention in an internal matter of the

Ottoman Empire, although Abdullah knew the British had arranged to become a

protector of the Emirate of Kuwait in 1899, had asserted their influence over

the Gulf States in 1903 with a series of high-profile diplomatic overtures, and,

ultimately, had made the military intervention against Egypt in 1882 which had

led to the long-term occupation of what was still, ostensible, an Ottoman

domain.

When the war with the Ottomans was imminent that autumn in 1914, Storrs

and Kitchener advocated restarting the negotiations, asking the sheriff to

declare any Ottoman fatwa of jihad against the Entente to be illegitimate. At

the same time, the Ottomans sought the sheriff’s endorsement for

their declaration of holy war. Sherif Hussein hesitated: he gave his

endorsement for their declaration of holy war but avoided public declaration

because it would invite aggression by the Entente powers against Muslims. The

disappointing response prompted the government in Istanbul to claim the sheriff

had approved of the call to jihad anyway, but they also sought ways to

neutralize the sheriff and his Hashemite family.

Meanwhile, Storrs offered an alliance with the sheriff if he would

promise to support the British war effort. In return Kitchener, as newly

appointed Secretary of State for War, was prepared to offer ‘independence’ to

the Arabs in the Hejaz. While ensuring their safety and freedom from the

Ottomans, what Kitchener had in mind was a caliphate that was spiritual, not

political.

Hussein delayed, knowing that he could not yet guarantee that many would

follow him and also that the Ottoman forces in the region would follow him, and

that the Ottoman forces in the region were strong enough to crush any premature

revolt. Moreover, his ambitions were initially unclear. Only later, once the

British had begun to secure their position in Palestine, Hussein began to

consider a role as leader.

Far from being a proto-nationalist struggle for the sake of Arabism,

this was a bid for dynastic security and an opportunity to replace the

secularists in Istanbul with a caliphate of his own.

Concurrently with Sherif Hussein’s planning was the conspiracy

of Al Fatat a Syrian secret society founded one year before the war.

Al-Fatat was the civilian equivalent of the militarydominated al-Ahd (the Covenant). This group's membership was

limited largely to army officers. It advocated the establishment of autonomous

entities for all ethnic groups within the empire; each group was to be

permitted to use its native language, although Turkish would remain as a

lingua franca. AI-Ahd maintained a central

office in Damascus. After the outbreak of war, the two movements would merge.

Al-Fatat approached Hussein to enquire whether he would lead the

movement against the CUP government in Istanbul. Hussein again hesitated, but

the discovery in February 1915 of Ottoman plans to have him arrested and

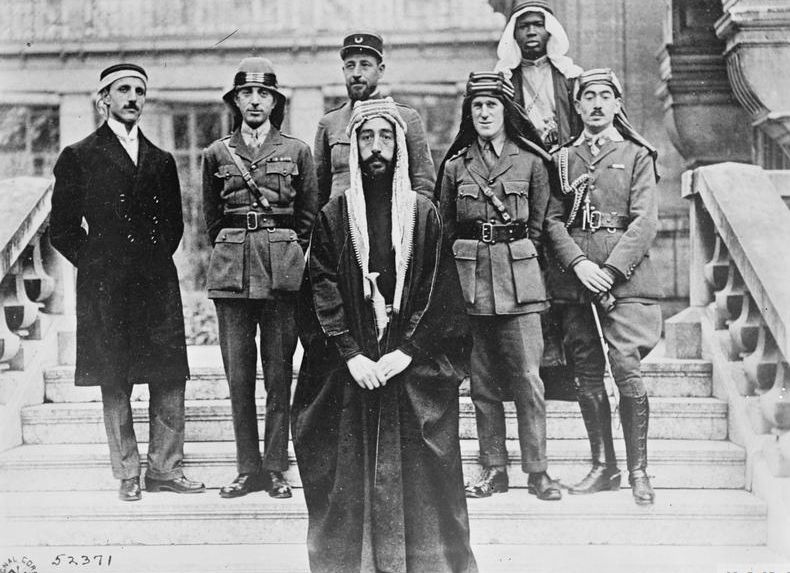

executed compelled the sheriff to act. He sent his son Faisal to gather

intelligence about the groups in question.

Meeting the conspirators, Faisal discovered that the nationalists were

concerned that, if the Ottomans were defeated, the French would make a bid to

take over Syria. Yet, they were reassured by news of secret talks between

Faisal’s brothers, Abdullah and Kitchener.

Al-Fatat thus drew up their plans, defined in the Damascus

Protocol. They desired an alliance with Great Britain, to provide military and

naval protection, and accepted the principle of economic preference for the

British Empire. In June 1915, these plans and the Ottoman demands were

considered by Hussein and his sons, before being presented as terms for

cooperation with the British at Cairo. In exchange for letters, the Hashemites

claimed to represent the ‘Arab nation’.

The British reaction was to

dismiss this extensive claim to represent the Arab ’nation’, but there was some

sympathy for a Sherifian revolt that might

potentially tie down thousands of Ottoman troops.

Britain And The Collapse Of

The Ottoman Empire In The Middle East

On the eve of the war with the Ottoman Empire, the Foreign Office was

convinced that because it lacked the necessary expertise, it had to defer to

the India Office and the Government of India when it came to exploiting

existing Arab discontent with their Turkish masters. The India Office and the

Foreign Office were agreed that it would be greatly advantageous to induce the

Arabs to side with Great Britain, but the Government of India was very much

against any policy initiative that might give the Muslim population of India

the impression that Britain actively tried to set Muslims against Muslims. The

Foreign Office, moreover, was very keen not to offend French susceptibilities

on Syria, which France considered her domain reservé.

Despite the Arabs’ great potential to weaken the Ottoman Empire’s war effort,

Indian Muslim anxieties and French–Syrian ambitions dictated a very cautious

response to Arab nationalist overtures to gain Britain’s support for their

schemes to revolt against Turkey.

The British authorities in Cairo had far fewer scruples about exploiting

Arab nationalist sentiment. The appointment of Lord Kitchener, the British

agent, and consul-general in Egypt, as secretary of state for war at the

beginning of August 1914, provided an excellent opportunity to push their

views. Together with Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey, Kitchener drew up a

telegram informing Cairo that the Arab movement should be encouraged in every

way possible. In October 1914 Kitchener also drafted a message, approved by

Grey, to Sharif Abdullah, the second son of Hussein the Emir of Mecca,

guaranteeing support for the Arabs if they assisted Britain in the war against

Turkey. These initiatives bore no fruit, however, and when the India Office and

the Government of India found out about them, they strongly protested,

stressing their deleterious effects on Indian Muslim feeling and relations with

France. The officials at the Foreign Office shared these misgivings. At the

beginning of January 1915, the policy of restraint on the Arab Middle East was

again in the ascendant.

What happened next is that one of Sherif Hussein of Mecca ‘s sons,

Faisal, went to Istanbul in March 1915 and stopped in Damascus to meet with

representatives of the Fatah secret society along with his way. Faisal told

them of Kitchener’s above-mentioned letter to his father in October 1914 and

stressed that no revolt would be possible without European assistance. On his

way back in May 1915, Faisal saw them again – this time ready to accept the

possibility of organized revolt. Fatah issued him with the ‘Damascus Protocol’

– a program for Arab independence under Hashemite leadership. The scheme

provided for Britain’s recognition of Arab independence along specific

boundaries, the abolition of foreign Capitulations, the conclusion of a

defensive alliance between Britain and the Arab state, and the granting of

economic preference to Great Britain. Faisal handed the Damascus Protocol to

his father and recommended that he agree to lead the revolt. Hussein entered

negotiations with Britain, but the Syrian soldiers with membership in Fatah and

‘Ahd were sent to the Gallipoli front with the

Ottoman Arab divisions after their mutinous plans were discovered by the

Ottoman secret service. This delayed the possibility for revolt but left time

for British authorities and the Ottoman Sultan to reach terms.1

Hussein had already garnered some popular support for an Arab Caliphate,

which came from within the British sphere of influence in Egypt and Sudan. At about

the same time in the Spring of 1915, Hussein finally acquired the support of

the heterogeneous Arab nationalist movements in Syria and Iraq to lead them in

an anti-Ottoman revolt. The issues of the Caliphate and the nationalist revolt

are discrete but inseparable. They illuminate how it came to be that Hussein,

who had very little connection to Arab nationalists before the war, came to

lead them by 1916. It also highlights how the divergent expectations within the

Arab movements, and between them and Britain, led to explosive political

violence between 1918 and 1920, and even until 1923.

On behalf of ‘the Arab nation’, Abdullah declared that it was in Great

Britain’s interest to support the Arabs in their endeavors to gain

independence, and that the Arabs, ‘in view of the well-known attitude of the

Government of Great Britain’, would gladly accept Britain’s assistance,

provided she accepted, within 30 days of the receipt of the note, the following

conditions:

1. Great Britain recognizes the independence of the Arab countries which

are bounded: on the north by the line Mersin-Adana to parallel 37° N and thence

along the line Birejik–Urfa–Mardin–Midiat–Jazirat (Ibn ‘Umar)–Amadia to the Persian frontier; on the east, by the Persian

frontier down to the Persian Gulf; on the south, by the Indian Ocean (with the

exclusion of Aden whose status will remain as at present); on the west, by the

Red Sea and the Mediterranean Sea back to Mersin.

2. Great Britain will agree to the proclamation of an Arab caliphate for

Islam.2

However familiar these conditions sounded to people like Gilbert Falkingham Clayton and Ronald Storrs, they nevertheless considered them

excessive. It was one thing in the battle against ‘Turco–German Jehad

propaganda’ to sympathize vaguely with Arab nationalist pretensions, even to

encourage them, but it was quite another actually to accept such precisely

worded proposals as those of Abdullah. In March, Clayton had already opposed

the proclamation favored by Francis Reginald Wingate

and George Stewart Symes, not only because such a

proclamation laid Great Britain open to a charge of breach of faith, but also

because he could not see ‘any practical possibility of the formation of

an Arab Empire’. The idea was ‘an attractive one but the necessary elements

appear to me to be lacking’.3

Now it seemed, so Clayton explained to Wingate in a hurried letter on 21

August, that ‘the High Commissioner will have to send a vague reply saying that

it is early days to begin negotiating agreements, the first thing being to oust

the Turks from Arabia’.4 Storrs shared Clayton’s point of view. The Sharif had

‘received no sort of mandate from other potentates. He knows he is demanding,

possibly as a basis for negotiation, far more than he has the right, the hope

or the power to expect.’5 19 August Sir Henry agreed with his advisers. On 22

August he telegraphed to London that Hussein:

Has of course at present no mandate beyond Hedjaz. His pretensions are

in every way exaggerated, no doubt considerably beyond his hope of acceptance,

but it seems very difficult to treat with them in detail without seriously

discouraging him.6

McMahon reached the conclusion that it was ‘quite interesting, and it

shews the need of great care in our relations with the Sherif’.7

The Foreign Office recognized the danger inherent in promoting an Arab

Islamic authority in Mecca to rival the Sultan. It would divide the Muslim

world and could threaten a future peace settlement. In April 1915, the Foreign

Office cabled Henry McMahon, High Commissioner in Egypt, saying: his Majesty’s

Government consider that the question of Caliphate is one which must be decided

by Mahommedans themselves, without the interference of non-Mahommedan Powers.

Should the former decide for an Arab Caliphate, that decision would therefore

naturally be respected by his Majesty’s Government, but the decision is one for

Mahommedans to make. Sherif Hussein of Mecca had already garnered some popular

support for an Arab Caliphate, which came from within the British sphere of

influence in Egypt and Sudan. There had been numerous schemes brought to the

attention of British officials in Egypt which envisioned alternative Arab

caliphates.

The British policy of restraint on the Middle East was a source of

constant concern for the authorities in Cairo and Khartoum. Their anxiety was

strengthened by the fact that the Germans and Turks seemed to be very much

alive to the vital importance for the progress of the war of definitely

estranging the Arabs from the British. It appeared to them that the central

powers would not hesitate to use whatever means at their disposal to bring this

about, and to their minds the adoption of an active, pro-Arab policy

constituted the only adequate answer to these ‘Turco–German machinations.'

However, such a policy could only be initiated if they were able to overcome

the existing obstacles of French-Syrian pretensions and Indian worries about

Muslim susceptibilities. During the first eight months of 1915, they made

several attempts to do so. These were singularly unsuccessful as far as French

aspirations were concerned. Sir Edward Grey and his officials were not prepared

to jeopardize relations with France to win the support of the Arabs. They did,

however, meet with success regarding the objections of the India Office and the

Government of India to actively exploiting Arab discontent with Ottoman rule.

This had the result that the Foreign Office was prepared to respond favorably

to the Emir of Mecca’s overtures at the end of August 1915, India Office

protests notwithstanding.

Britain, the Arab movements, and the Hashemites thus became involved in

an alliance which bonded them together as long as there was an Ottoman enemy to

defeat. These common interests dissolved after October 1918.

The Al-Faruqi Myth

As a sideshow to this topic, there is the often overstated role of

Sharif Al-Faruqi. Following this, the Cairo military authorities believed that

the desertion of Sharif Al-Faruqi, an Arab officer from the Turkish army at

Gallipoli, who claimed to represent an organization of Arab officers in the

Turkish army in contact with the Arab chiefs, combined with Sharif Hussein’s

reply to Sir Henry McMahon’s letter of 30 August, provided a golden opportunity

to spur the home authorities into action regarding the Arab question.

To the surprise of his interrogators, Faruqi informed them that he was

part of a wide conspiracy whose ultimate objective was to bring about an

uprising of Arab troops in Syria. He was a member of a

secret organization of Arab officers within the Ottoman army called

al- ‘Ahd, which he had originally joined in Mosul;

but after his unit had moved to Syria he had also become a member of another, a

somewhat older secret organization of Arab nationalists known

as Jam‘iyya al-‘Arabiyya al-Fatat

– the Young Arab Society. Al-Fatat had been founded by a small group of

civilian Arabs in Paris in 1911 and had recently moved its headquarters from

Beirut to Damascus while al-‘Ahd had been

established in October 1913 in Istanbul.8 In January 1915, the leaders of both

al-Fatat and al-‘Ahd had joined forces in

Damascus where they decided to send a message to Sharif Husayn of Mecca stating

that they were ready to start a rebellion in Syria under his leadership.

On receiving this dramatic information, Faruqi’s interrogators informed

British Intelligence in Cairo, whose chief, Brigadier Gilbert Clayton,

immediately issued orders for the Arab lieutenant to be sent to Egypt for

further interrogation. He arrived there on 1 September 1915 and the following

day was introduced to Na’um Shuqayr, a Lebanese Christian who worked for British

Military Intelligence and who was to be his ‘minder’ and translator. Shuqayr lived in a small house in the old al-Qahira

district and Faruqi was instructed that, for the time being, he should live

with Shuqayr. Each day they walked the two miles

from Shuqayr’s home to the HQ of the

British Army at the Savoy Hotel, where Faruqi was ordered to begin writing a

detailed account of all he knew about the activities and plans of al-'Ahd. By 12 September Faruqi’s long statement, describing

the situation of the ‘Arab movement’ in Syria prior to his desertion, the aims

of the movement, and his own role within it, was completed and typed up, ready

for analysis. It was immediately passed to Brigadier Clayton and was to be the

catalyst that would culminate in a dramatic turn in British policy towards the

Arabs and the Middle East. Over the next few days, Clayton read and re-read

Faruqi’s statement with a mixture of concern and excitement. Faruqi stated

that, having met with the leaders of both al-Fatat and al-‘Ahd in

Damascus, he had ‘thought of uniting the two societies in order to gain

strength by the union and to avoid mistakes in politics which history teaches

us might occur from the military if left alone’, and indeed, it was he himself

– so Faruqi claimed – that united the two organizations.9

The newly united body then carried out propaganda among Arab units and

his organization agreed that they were prepared to give Britain, in return for

its help, ‘all concessions and privileges which do not touch the essential

resources of our country and our independence’. The first action of the new

Arab organization had been to send an officer to the Sharif of Mecca,

after which they discovered that the Sherif was already in communication with

the high commissioner in Cairo and that ‘the English have given their consent

for the Sharif establishing an Arab Empire, but the limits of his Empire were

not de- fined.’ Faruqi then went on to describe the circumstances of his

subsequent arrest in Aleppo, his imprisonment during which the Turkish

commander Djemal Pasha had tried – but failed – to get him to reveal what he

knew about ‘the secrets of our society’. He and the other officers imprisoned

with him were then released but ‘sent to Istanbul’. During the journey, he and

some of his companions tried to escape to Cyprus and from there to travel to

Mecca and join the Sharif, but they failed as ‘we were under close

surveillance’. On arrival in Istanbul they again ‘tried to escape but we could

not get a chance of doing so’, after which Faruqi ‘was detailed as a commander of

an infantry company fighting at Gallipoli’. He deserted at Gallipoli because he

did not want to fight ‘my friends’ or do ‘service to my enemies … the Turks –

who wish to kill me and my party’.

Some parts of the statement must have sounded rather odd to Clayton. It

is then maintained by a number of authors that Clayton began to push these

doubts into the back of his mind as Faruqi’s statement became more and more

interesting. ‘Ninety percent of the Arab officers in the Ottoman Army’ were

‘members of our society’, he claimed, and not only Arabs but part of the Kurd

officers’.10

Al-Faruqi himself would ‘guarantee to go to Mesopotamia and bring over a

great number of officers and more especially from the 35th Division at Mosul

who all know me’. And as if to emphasize the strength of the Arab movement of

which Faruqi was, he claimed, a leading member, Shuqayr recorded

that Faruqi had told him that if Britain did not agree to support the Arabs,

they would get their independence by themselves.11

Yet Faruqi was certainly not pivotal. His testimony

rather was used by Clayton and Maxwell to so-called 'rub it in'.

Faruqi's claims simply looked like a good excuse to help let London finally

make a political decision toward a more active pro-Arabic direction. Thus in a

letter sent to Wingate Clayton describes Faruqi as 'not a bad little man'

(Wingate papers, box 143A/7).

Also Sir Edward Grey was receptive to the promptings from Cairo. At the

same time, Grey and the officials at the Foreign Office realized that the

boundaries claimed by the Arabs clashed with French ambitions in Syria, as well

as those of the Government of India in Mesopotamia. An obvious way out of this

problem seemed to them to be to sacrifice Indian interests in Mesopotamia to

persuade the French to be more accommodating in Syria. McMahon was authorized

to react favorably to Hussein’s territorial claims in as far as Britain was

free to act without detriment to the interests of France. For the Foreign

Office, the time had now arrived to open negotiations with the French on the

extent of their claims in Syria. The Government of India and the India Office strongly

protested against the disregard of India’s territorial ambitions in

Mesopotamia, but they got nowhere with Sir Edward. The only comfort he could

give them was that, given the weakness of the Arabs, nothing would come of

these schemes. When the British cabinet decided to evacuate Gallipoli,

Kitchener warned that this would prevent the Arabs from siding with the

Entente. He strongly advocated a landing at Alexandretta as a countermeasure.

The French, however, refused to entertain this proposal, and the project was

subsequently dropped. On the eve of the negotiations with the French on the

boundaries of the future Arab state, Grey and the officials in the Foreign

Office realized that, unless the Entente intervened with military force in the

Middle East, there was no prospect of the Arabs rising against the Turks. At

the same time, they insisted that French claims on Syria preclude such an

intervention from taking place without French permission and active

participation.

As Clerk minuted ‘all Arab

discussion is futile unless we (and the French) are prepared to give armed

support in force’.12 Grey concurred. He minuted on

a telegram from McMahon that ‘nothing will move the Arabs in our favor except

military action giving them protection against the Turks. Unless we can effect

this, negotiations and promises will be useless and embarrassing.13 One of

Clayton’s ‘golden opportunities’ again seemed to slip away. Not because the

Foreign Office did not realize how important it was to bring the Arabs over to

the side of the Entente – thanks to the incessant lobbying by Wingate, Clayton,

Storrs, Maxwell, McMahon, and Kitchener, it had become thoroughly aware of that

– not because the India Office and the Government of India had been successful

in obstructing initiatives in this direction, but because Kitchener and the

authorities in Cairo and Khartoum once again faced a far more formidable

obstacle: the Foreign Office’s refusal even to think of a Middle East policy

not based on a sympathetic attitude towards French ambitions in Syria.

Also, Ian Rutledge writes in

"Enemy on the Euphrates: The Battle for Iraq, 1914-1921"(2015) that:

'Nevertheless, in all other respects Sykes had done it – or so he believed. He

had squared the circle. He had made an agreement with Picot which satisfied

both Britain and France while at the same time believing that he was broadly

respecting the wishes of Sharif Husayn and the ‘Arab movement’ as related to

him by their ‘representative’ Lieutenant Faruqi. Needless to say, neither

Sharif Husayn nor his sons had the slightest idea that their objectives had

been so seriously misconstrued by the Power to whom they were about to commit

their forces and in whose service they were to risk all.' This 'had squared the

circle', should be seen as referring particularly to the Arabs in the sense

that he perceived them as weak and divided and thus did not really want to give

them as much as they believed they had been promised.

The Syke-Picot

discussions and its consequences

The first meeting of the British interdepartmental committee headed by

Sir Arthur Nicolson with François Georges-Picot took place on 23 November 1915.

The French representative was not convinced of the importance of inducing the

Emir of Mecca and the Arab nationalists to side with the Entente. Austen

Chamberlain reported to Lord Hardinge that Picot had ‘expressed complete

incredulity as to the projected Arab kingdom, said that the Sheikh had no big

Arab chiefs with him, that the Arabs were incapable of combining, and that the

whole scheme was visionary’. The secretary of state for India was very pleased.

It seemed that the French delegate ‘knows his Arab well. I expect he has sized

up the Sheikh’s scheme pretty accurately. I doubt if it has any element of solidity

or that any promise will have weight with the Arabs until they are absolutely

convinced that we are winning.’14

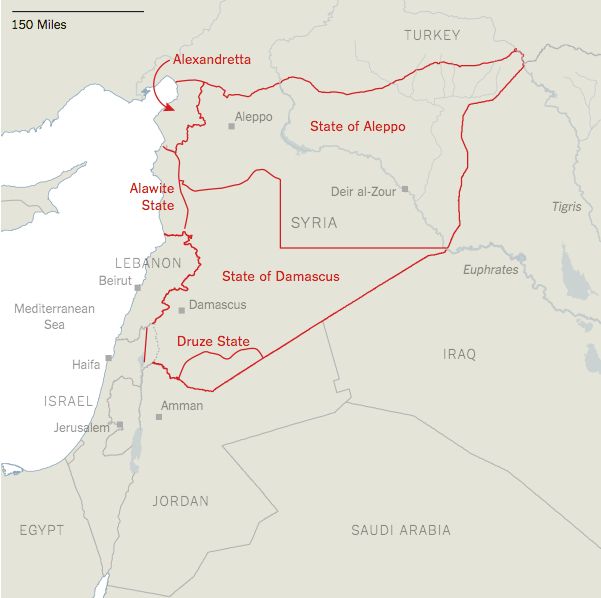

Moreover, French demands – which according to Picot the French were

obliged to make as ‘no French government would stand for a day which made any

surrender of French claims in Syria’ – were rather excessive. Picot informed

the Nicolson committee that France claimed the:

Possession (nominally, a protectorate) of land starting from where the

Taurus Mts approach the sea in Cilicia, following the Taurus Mountains and the

mountains further East, so as to include Diabekr,

Mosul and Kerbela, and then returning to Deir Zor on the Euphrates and from

there southwards along the desert border, finishing eventually at the Egyptian

frontier. Picot, however, added that he

was prepared ‘to propose to the French government to throw Mosul into the Arab

pool, if we did so in the case of Bagdad’. In amplification, Nicolson minuted that Picot had:

Intimated his readiness to proceed to Paris to explain personally our

view – and the Arab desiderata. M. Cambon told me that he had objected to this

visit, on the ground that he would not be well received at the Quai d’Orsay

were he to carry with him such unpalatable proposals as he had suggested. M.

Picot would, therefore, communicate with Quai d’Orsay in writing. We must,

therefore, await the reply.15

Thus started the negotiations between the British and the French, and

subsequently followed by the British, the French and the Russians, to settle

their claims on the Asiatic part of the Ottoman Empire. The Foreign Office

started these negotiations because it considered that they had to be brought to

a successful conclusion before the Emir of Mecca could again be approached

regarding the terms under which the Arabs would be pre- pared to side with the

Entente. A settlement should also secure French consent to a military

intervention on the coast of Syria, providing a screen behind which the Arabs

would rise against the Turks. During the negotiations, which started at the end

of November 1915 and finally came to an end in the middle of May 1916, Sir

Edward Grey and his officials again and again stipulated that an agreement only

held good if the active cooperation of the Arabs was secured. At the same time

they were well aware that, after the British and French governments had decided

at the end of December 1915 to concentrate their forces on the Western front

and that the amount of troops on the other fronts should be reduced to the

barest minimum, a military intervention on the Syrian coast was out of the

question and Arab active assistance consequently would never materialize. This

had at least the advantage that critics of the negotiations could easily be

disarmed by pointing out that nothing would ever come of all this. Not three

weeks after an exchange of letters between Grey and French ambassador Paul Cambon

had finalized what would become known as the Sykes–Picot agreement, Sharif

Hussein started his revolt against his Turkish masters. That the Emir revolted

without waiting for a fresh round of negotiations or a military intervention by

the Entente drew no comments from Grey and his officials.

The Cairo authorities to impress on the Foreign Office that the object

of the negotiations with Hussein was not to gain the Arabs’ active assistance,

but rather their passive support in order to prevent a jihad. They also tried

to make clear to the home authorities that Arab opposition to French ambitions

in Syria was real and could not be ignored, that there were divisions in the

Arab nationalist camp, and that as a result of a rapprochement between the

Turkish opposition parties and the Arab nationalists, it was inopportune to

divulge the terms of the Sykes–Picot agreement to Hussein. The main result of

these efforts to educate Grey and his officials on the true state of Arab

feeling was that the latter grew heartily tired of the whole affair.

There were also the various crises that erupted in London from September

1916 to January 1917 as a result of a series of requests by the authorities in

Cairo and Khartoum to send a

British brigade to the town of Rabegh on the coast of

the Hijaz to prevent the Turks from advancing on Mecca and crushing Sharif

Hussein's revolt. These requests offered ministers dissatisfied with the manner

in which the war was being conducted the opportunity to challenge the

established military policy of concentrating all available forces on the

Western front in France. However, to overthrow this policy was quite another

matter. At times, the War Committee hovered on the brink, but in the end, it

always decided to postpone the decision, even when it had been decided to take

a decision. When in December the newly created War Cabinet decided to delegate

the responsibility for sending the brigade to Sir Reginald Wingate, the latter,

although he had been the most ardent advocate of the scheme, promptly shifted

it onto Hussein, who in the meantime had been proclaimed ‘King of the Arab

Nation’, his precarious position notwithstanding. By the middle of January

1917, it was evident that Hussein would not permit British troops to land in

the Hijaz. This proved to Wingate’s satisfaction that, if the Arab revolt

collapsed, the blame lay firmly on Hussein’s shoulders. There would be no

further Rabegh scares.

Meanwhile Mark Sykes traveled to see Hussein and managed to convince the

king that he could safely assent to a formula to the effect that the French

would pursue the same policy in Syria as the British in Baghdad. Hussein had

apparently gained the impression that Baghdad would be part of the Arab state,

and afterwards showed himself to be very pleased that he had tricked Picot into

giving Syria away. According to the Sykes–Picot agreement, however, Baghdad

would be ‘practically British’, in which case the king had unwittingly agreed

to Syria being ‘practically French’. It did not take long before the Foreign

Office received the first reports indicating that, as far as informing King

Hussein of the terms of the Sykes–Picot agreement was concerned, the Sykes–Picot

mission had been a signal failure.

Having discussed the previous month Mark Sykes

is one of the more fascinating persons figuring in British policy making

towards the Middle East 1914–19. At the beginning of 1916, Sykes established a reputation as an

effective negotiator. His reputation was further strengthened by his

appointment as assistant secretary to the War Cabinet, but it began to wane

when in the summer of 1917 there were signs that he had failed to impart to

King Hussein a clear understanding of what the Sykes–Picot agreement meant, and

it was fatally injured at the end of 1917, when it became clear that the French

government would not ratify the projet d’arrangement Sykes had negotiated. What makes Sir Mark

fascinating is that he did not hesitate to put the most fantastic, outrageous

observations, theories and schemes to paper and circulate them to whomever

might be interested. His observations on the influence of the Jews on the war

efforts of the belligerents did perhaps not raise too many eyebrows, because

these were very common at the time, but this certainly did not apply to his

various schemes about how French, Arab, Armenian, Zionist and whoever else’s

interests could be combined and reconciled, and put to work in support of the

British war effort. It is hard to believe that anyone for one moment took these

seriously, or was ready to entertain them, but it was very seldom that they

were openly ridiculed.

As for Hussein there also was, of course, the question of money. Clayton

informed Wingate that Hussein Hussein had: Confessed to Wilson that he had saved about

£200,000 out of the first two consignments of £125,000 sent to him, and Faisal

was exceedingly angry at the difficulty he had in getting money out of his

father for himself and Ali […] £100,000 gold- en

sovereigns sent to Feisal and Ali a couple of months ago would have done

wonders. Wilson has spoken very seriously to the Sherif and is going to do so

again and warn him that he is jeopardizing his success by his parsimony.16

On 10 April 1917, Wingate telegraphed to the Foreign Office that Hussein

had requested that his monthly subsidy is raised. According to the high

commissioner, the King deplored the fact that he had to make this request,

especially given ‘his heavy financial and other obligations to His Majesty’s

Government’, but then again, from his revolt ‘serious political and military

benefits’ had accrued to Great Britain. Sir Reginald added that Hussein would

use the extra money ‘to secure the adhesion of chiefs of northern tribes and

thereby to achieve that semblance of national cohesion which can (?justify) his

revolt […] in the eyes of the Moslem world’. Given the latter, in particular,

it seemed to Wingate to ‘be bad and possibly dangerous policy on our part to withhold

additional financial backing which he requires at a time when tribal elements

east of the Jordan can render effectual assistance to our own military

operations in Palestine.' He, therefore, did not hesitate to recommend strongly

the granting of Hussein’s request.

During the summer and autumn of 1917, officials of the Foreign Office,

the India Office, the War Office and the Treasury met regularly to discuss the

situation, while Sir Reginald time and again tried to force the issue. On 18

June, Wingate urged that Hussein’s ‘monetary requirements’ be met to prevent

unfortunate political effects ‘on Arab military operations’, and one month

later he stated that not meeting Hussein’s demands ‘would be little short of

disastrous and effect on Arab military operations hardly less so’.17 The Arab

revolt, however, still continued when on 10 October the Treasury finally agreed

to place £400,000 in gold at the disposal of the Egyptian treasury.18 This

matter had hardly been settled when Sir Reginald asked permission that ‘additional

£25,000 a month which has already been promised to Shereef for five months

after fall of Medina be given him now, and that it be continued for a maximum

period of 5 months irrespective of date on which Medina may fall’. The high

commissioner fully realized that ‘Shereef’s method of administering his

finances is by no means beyond criticism’, but the situation in the Hijaz once

again was ‘critical’, and it was Wingate’s considered opinion that Great

Britain should not, ‘for the sake of a relatively small sum of money, lose the

full fruits of a policy which I venture to think has fully justified itself

both from a military political and financial point of view’. This was exactly

what was bothering Clerk. He doubted very much ‘if another £25,000 a month is going

to keep the Arabs together, supposing they are in the condition Sir R. Wingate

describes’. He wondered whether the time had not arrived that ‘we should rely

on our own forces and refuse to be a milk cow for King Hussein’. Graham had no

difficulty with the proposal, as it was the high commissioner’s responsibility,

but he agreed with Clerk that ‘the Arab movement must be very unstable if

£25,000 a month makes all the difference to it!’19

However, the authorities in Cairo, Baghdad, and London steadily lost

their grip on the continuing and deepening rivalry between Husayn and Ibn Sa’ud, in particular regarding the possession of the desert

town of Khurma. This led to the First Saudi–Hashemite

War, also known as the First Nejd–Hejaz War.

The war came within the scope of the historical conflict between the

Hashemites of Hejaz and the Saudis of Riyadh (Nejd) over supremacy in Arabia.

It resulted in the defeat of the Hashemite forces and capture of al-Khurma by the Saudis and his allied Ikhwan, but British

intervention prevented an immediate collapse of the Hashemite kingdom,

establishing a sensitive cease-fire.

The British–French rivalry in the Hijaz; the British attempt to get the

French government to recognize Britain’s predominance on the Arabian Peninsula;

the conflict between King Husayn and Ibn Sa’ud, the

Sultan of Najd; the British handling of the French desire to take part in the

administration of Palestine; as well as the ways in which the British

authorities, in London and on the spot, tried to manage French, Syrian, Zionist

and Hashemite ambitions regarding Syria and Palestine, in the end, has two

major underlying themes. The first is the rapid erosion of Sir Mark Sykes’s

authority on Middle Eastern affairs in the months from December 1917 to August

1918. His proposed solutions for the disentanglement of the mass of knotty

problems with which Britain was confronted found less and less favor and were

increasingly ignored or rejected. At the end of this period, Sir Mark stood

more or less on the sidelines of the decision-making process regarding the

Middle East. There is quite some irony here, like Sykes, at his request, had

moved to the Foreign Office at the beginning of January 1918 in an attempt to

become the directing actor in British Middle East policy. The second underlying

theme concerns the concomitant undermining of the Foreign Office doctrine that

no effort should be spared to accommodate French susceptibilities on Syria. In

Cairo and Palestine, Sir Reginald Wingate, Gilbert Clayton and General Allenby

championed the cause of the Arabs, sheltering behind military exigencies, while

in London, Arthur Balfour and Lord Robert Cecil failed to put their stamp on

the decision making within the inter-departmental Eastern Committee chaired by

Lord Curzon.

During the discussions during and following the Paris Peace Conference

in 1919 the British authorities – in London, Paris and the Middle East –

gradually came to realize that, in contrast to what they had initially

believed, they could not dictate terms to the French with respect to Syria.

When the peace conference opened in January 1919, they might have differed

among themselves about the best way to secure British interests in the Middle

East, but they all shared the presumption that Great Britain could negotiate

with the French from a position of strength. It was only a question of time

before the latter would understand that they had no other option than to give

in to British demands. British forces occupied the country, the USA strongly

opposed French imperialistic designs, and if France nevertheless succeeded in

pushing through her ambitions and tried to occupy the country, Arab armed

resistance would lead to bloodshed on a scale France could scarcely afford. It

was only through Britain’s good offices that France would be able to secure

Syria by peaceful means. By the end of August it had become clear that all this

had been an illusion. In January it had already been realized that the costs of

occupation constituted an intolerable burden for the British treasury, but

there remained the possibility of American intervention and there was still the

threat of the Arab nationalists attacking French soldiers. By May, however,

everything indicated that the Americans would not take a stand on Syria, and by

July the Arab threat more or less evaporated as a result of a more realistic

appreciation of the strength of the Arab forces under Faisal’s command. Prime

Minister David Lloyd George nevertheless thought he could still settle matters

in Britain’s favor by presenting the French with the fait accompli of a British

evacuation of Syria as of 1 November, and handing over the towns of Damascus,

Homs, Hama and Aleppo to Faisal’s forces in pursuance of the British agreement

with the Emir of Mecca. He believed that French prime minister Georges

Clemenceau would not dare run the risk of an armed confrontation. Clemenceau

did not even blink. He demanded that the British put a stop to their meddling

in the Syrian question, and leave it to the French to deal with Faisal and the

Arab nationalists. By the middle of October, it was Lloyd George who gave in.

Faisal was left to fend for himself.

The French, who opposed his plan, defeated his army in July. But even if

they hadn’t, Faisal’s territorial claims would have put him in direct conflict

with Maronite Christians pushing for independence in what is today Lebanon,

with Jewish settlers who had begun their Zionist project in Palestine, and with

Turkish nationalists who sought to unite Anatolia.

In conclusion, it is possible to understand Britain’s contradictory

policy commitments which were made as British war aims evolved along with the

conditions produced by the conflict.

What they understood about the connection between the Hashemite family

and Arab nationalist societies differed from the actual relationship.

Another leitmotif was that the officials at the Foreign Office had no

thought-out conception of what British Middle East policy should be, but judged

developments in that area by the simple rule that nothing should be done that

might arouse France’s susceptibilities on Syria.

And while it is significant that in 1917, Britain somehow expected an

Arab-Islamic empire to take shape. British policymakers were never fully aware

of the social and political connections between the Hashemites, the secret

societies called Fatat and 'Ahd, and the

pan-Islamists. This is because they did not understand, or chose to overlook,

how deeply engrained religious notions of power were within these secret

societies.

At the end of the war, Sherif Hussein was left only with the stony and

unproductive Hejaz, in which he imposed a regime of ultrastrict shari‘a, restoring punishments such as hand and foot

amputation which had fallen into disuse in the region long before the Young

Turk revolution. At the same time, he began to behave increasingly like the

archetypal ‘oriental despot,' alienating rich and poor alike. In March 1924

Husayn proclaimed himself caliph after the Turkish Nationalist government had

formally abolished the role. In response, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz Ibn Sa‘ud

of Najd sent his feared Ikhwan fighters into Husayn’s realm and the king was

forced to flee to ‘Aqaba in ‘Abdallah’s Transjordan, from where the British

removed him to Cyprus. He later returned to Transjordan’s capital, Amman, where

he died in 1931.

It should therefore not come as a surprise that Amman

was foremost in celebrating, what inspired by T.E. Lawrence is today,

called the 'Arab Revolt'.

Conclusion: From Sherifian to a

real ‘Arab revolt’ in Iraq

If we were to ask the question, ‘On whose side did the Arabs fight in

the First World War?’ Most people who know something about the war’s history

would probably say ‘Britain’s.' Such a

reply would reflect the orthodox account, emanating from the glorification of

‘Lawrence of Arabia’ and the alleged ‘Arab Revolt’ of Sherif Hussein and his

sons, an episode also burned into the imagination by David Lean’s spectacular

and immensely popular film on this subject. In both the film and Lawrence’s

original memoir – The Seven Pillars of Wisdom – we see an epic struggle in

which ‘the Arabs’ join with the British in a fight to the death against the

former’s cruel Turkish overlords. In return, the British promise the Arabs

‘freedom’, for their contribution to winning the war in the Middle East, a

promise which would never be redeemed. This ‘orthodox narrative’ is also

exemplified by the writings of some Arab historians who interpreted the

pro-British stance of the Hashemites as part of an ‘Arab awakening’ after centuries

of Turkish domination.

However, over the last two decades, this orthodox narrative has been

questioned by a number of historians – not just the role claimed by Lawrence himself,

but more fundamentally the assumption that Britain’s opponents in the Middle

East were almost entirely ethnic Turks, that the Arabs’ experience of the

Ottoman state was little more than a ‘Turkish yoke’, and from the outset they

were only waiting for an opportunity to rebel against it.

In reality, the vast majority of Arabs did not ‘fight for the British’

in the First World War. In 1914 about one-third of the regular troops in the

Ottoman army were Arabs, mainly from the towns and cities of the regions which

subsequently became Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Palestine.

However, between July 1920 and February 1921, in the territory then

known to the British as Mesopotamia – the modern state of Iraq – an Arab

uprising occurred which came perilously close to inflicting a shattering defeat

upon the British Empire. The story of this uprising is one which once engaged

the closest of attention among the British public but over many decades slipped

back into the mists of exclusively academic history, almost completely erased

from the collective memory.

And so it would have remained had it not been for the ill-fated US

invasion of Iraq in 2003. Once the ‘insurgency’ against the subsequent

occupation had begun, it wasn’t long before a much older, forgotten insurgency

in Iraq came to light with journalists, historians and even functionaries of

the US occupation drawing lessons and making comparisons – some appropriate,

some less so – with that much earlier event.20

The Iraqi revolt against the British, also known as the 1920 Iraqi

Revolt or Great Iraqi Revolution, started in Baghdad in the summer of 1920 with

mass demonstrations by Iraqis, including protests by embittered officers from

the old Ottoman army, against the British occupation of Iraq. The revolt gained

momentum when it spread to the largely tribal Shia regions of the middle and

lower Euphrates. Sheikh Mehdi Al-Khalissi was a

prominent Shia leader of the revolt.

Sunni and Shia religious communities cooperated during the revolution as

well as tribal communities, the urban masses, and many Iraqi officers in Syria.

The objectives of the revolution were independence from British rule and

creation of an Arab government.

The Foreign Office (FO) documents can be viewed online, here:

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/foreign-commonwealth-correspondence-and-records-from-1782

1 Tauber, The Arab Movements in World War I, pp 63–65.

2 Note, not dated, encl. in Abdullah to Storrs, 14 July 1915; Antonius,

Arab Awakening, p. 414. There were four other conditions, which McMahon summarised as follows: ‘Arab government of Sheriff to

guarantee Great Britain economic preference in Arab countries. Conditions of

mutual assistance. Great Britain to approve and further abolition of foreign

privileges in Arabia. Provisions of renewal of alliance.’ Tel. McMahon to Grey,

no. 450, 22 August 1915, FO 371/2486/117236.

3 Clayton to Wingate, private, not dated, presumably March 1915, Wingate

Papers, box 134/4.

4 Clayton to Wingate, private, 21 August 1915, Wingate Papers, box

135/2.

5 Storrs, Note, 19 August 1915, FO 371/2486/125293.

6 Tel. McMahon to Grey, no. 450, 22 August 1915, FO 371/2486/117236.

7 Minute Clerk, 23 August 1915, on Shuckburg

to Oliphant, 13 August 1915, FO 371/2486/112369.

8 Quoted in Roger Adelson, London and the Invention of the Middle East:

Money, Power, and War, 1902-1922,1995, p. 190.

9 FO/882/13, The National Archive, London, Memorandum on Military,

Political Situation in Mesopotamia (Section II), 28 October 1915.

10 Quoted in Adelson, p. 74.

11 Ibid., pp. 107–8.

12 Minute Clerk, 3 December 1915, on Parker to Clerk, 3 December 1915

(underlining in original), FO 371/2486/183416.

13 Minute Grey, not dated, on tel. McMahon to Grey, no. 732, 28 November

1915, Cab 37/138/ 23.

14 Chamberlain to Hardinge, private, 25 November 1915, Hardinge Papers,

vol. 121.

15 Clerk’s minutes of meeting Nicolson committee with Georges-Picot, on

23 November 1915, 1 December 1915, and minute Nicolson, 27 November 1915, FO

371/2486/ 181716

16 Clayton to Wingate, private, 24 September 1916, Wingate Papers, box

140/6.

17 Tel. Wingate to Balfour, no. 645, 18 June 1917, FO 371/3048/121588,

tel. Wingate to Balfour, no. 754, 18 July 1917, FO 371/3048/142636.

18 Treasury to F.O., no. 32359/17, 10 October 1917, FO 371/3048/195477.

19 Tel. Wingate to Balfour, no. 1153, 2 November 1917, and minutes Clerk

and Graham, 3 November 1917, FO 371/3048/210013.

20 See, e.g., Niall Ferguson, ‘This Vietnam Generation of Americans Has

not Learnt the Lessons of History’, Daily Telegraph, 10 April 2004; Robert

Fisk, ‘Iraq 1917’, Independent, 17 June 2004; also, before his replacement,

Paul Bremner, head of the Coalition Provisional Authority set up to administer

Iraq following the invasion, was reported as opining that the great mistake of

the Shi‘is had been to rebel against the British in 1920. See also The Iraqi

Independence Movement: a Case of Transgressive Contention (1918–1920) and Aula

Hariri Sectarianism in Iraq: The Making of State and Nation Since 1920 By

Khalil Osman 2014.

For updates click homepage

here