By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

A Strategy Beyond Revenge

Hence, today, at the time of writing King Abdullah of

Jordan met with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz in Berlin.

Further to our previous article, we take a wider

approach because even in the wretched history of terrorism, the assault that

Hamas carried out in Israel on October 7 stands out. Hamas fighters viciously

murdered more than 1,300 Israeli citizens, including elderly people, toddlers,

and babies. It was an intimate barbarism that revealed a total lack of moral

restraint and evoked memories of mass murders.

Comparisons to

another surprise attack on Israel—the Arab assault

that launched the 1973 Yom Kippur War—are misleading in one crucial

respect: the 2,656 Israelis who died then were exclusively soldiers.

One must return to the 1948 War of Independence to find

comparable Israeli civilian casualties. The attack also involved

hostage-taking on a massive scale, with roughly 150 people (mainly Israelis,

but also Americans and other foreign nationals) captured and taken to Gaza;

one Hamas leader vowed that the group would distribute video

recordings of hostage executions if Israel launched a counterattack.

There is no defending

or explaining such sadism. Repeated injustice and repression cannot excuse

atrocity. Israelis’ outrage and desire for vengeance is understandable. Defense

Minister Yoav Gallant states that Israel aims to wipe Hamas “off the face of

the earth.” The Israeli Foreign Ministry spokesperson, Emmanuel Nahshon,

called for “the complete and unequivocal defeat of the enemy, at any cost.”

But as the saying

goes, “Hope is not a strategy”—and neither is anger. Destroying an enemy’s

fighting force is a core principle of military strategy, but killing with

little discrimination or restraint places revenge ahead of logic. Instead of

merely reacting, Israel must make hard strategic and political choices not

because it is weak but because it is vital. As the United

States learned after the 9/11 attacks

2001, how a government responds to a major terrorist attack can set a country’s

trajectory for decades. And although this attack was particularly gruesome, it

was not unprecedented. In 2008, the Pakistan-based jihadi group Lashkar-e-Taiba launched an assault on Mumbai that likewise came from land and

sea, involved armed strikes against soft targets, and killed many civilians

(though not as many as the Hamas attack). Even as Israeli officials lament,

they can learn from what other governments have done in the aftermath of

massive terrorist assaults.

Terrorism is

incredibly challenging for democracies because it is an accelerator for war.

Elected leaders must regain the upper hand and replace fear with resolve.

Dispassionate strategic thinking in the aftermath of terrorist attacks is

complex, but it is the only way to end a group—which Israel says it wants to

do. The history of modern counterterrorism holds a clear lesson: only through

the strict targeting of a terrorist organization can a state permanently crush

it and avoid a wider conflict. For that reason, in addition to using its

traditional playbook of airstrikes, targeting leaders, and deploying troops,

Israel must protect innocent civilians, including Israeli hostages. This is not

merely a matter of morality and law but a strategic imperative. Israel risks a

calamitous failure if it conducts this campaign in a way that targets all

Gazans.

Does Hamas Have A Strategy?

Hamas’s foundational aim is the eradication of

Israel. But Hamas does not have the means to bring about Israel’s demise

directly. To believe otherwise would be delusional; Israel is militarily strong

and has the backing of the United States. So what

did Hamas think this bloodshed would achieve?

All terrorist groups

adopt at least one (and sometimes two) of the following strategies: compellence, polarization, provocation, and mobilization. A

superficial reading of the October 7 assault might suggest that Hamas sought to

compel Israel to alter its behavior by inflicting pain—as Hezbollah did in 1983 with its attacks on

American and French personnel and civilians in Beirut, which led Washington and

Paris to withdraw their forces from Lebanon. But compliance does not fit the

context of today’s Israeli-Palestinian conflict: Israel withdrew its

forces from Gaza in 2005, and no Israeli policy change could advance Hamas’s

long-term goal. What is more, if all Hamas wanted to do was kill Israelis, its

fighters would not have filmed their operations or taken hostages, actions that

reflect the fact that the attack on Israel was aimed at audiences beyond the

Israelis and was thus advancing a strategy other than competence.

Terrorist groups

often attempt to polarize the polities they target, carrying out attacks that

will pit one part of society against another and hoping that the state will rot

from within. Examples include the Armed Islamic Group’s atrocities in the late

1990s against entire Algerian villages full

of civilians who rejected their extremist principles and suicide attacks that

al Qaeda in Iraq launched in Shiite strongholds and against moderate Sunnis

from 2004 to 2006. But Israeli society was already deeply divided politically

before the Hamas attack—which, if anything, has at least partially unified

Israel. Hamas did not need to polarize Israeli society; in recent years, the Israelis

have accomplished that feat.

What Hamas was trying

to do, instead, was to provoke and mobilize. Terrorists often try to encourage

states into counterproductive overreactions. The nineteenth-century Russian

group undermined the tsarist regime of Tsar

Alexander II, which inspired a brutal state response. Killing the tsar also

killed Narodnaya Volya, but the regime could not

reform, and 30 years later, the Russian Revolution overthrew it. Many other

groups followed Narodnaya Volya’s example, notably

the Black Hand, the Serbian nationalist group

that lit the fuse of World War I by assassinating the Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914.

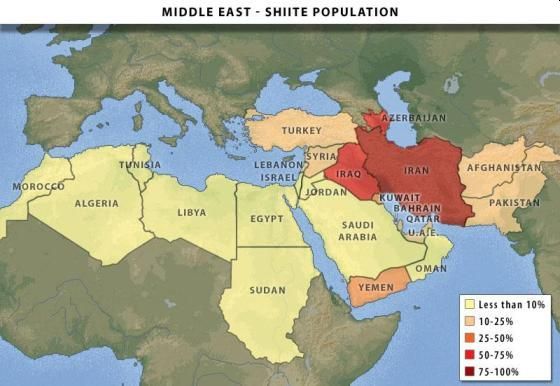

In the present case,

Hamas is likely hoping that an Israeli overreaction might reverse the

diplomatic momentum toward “normalization” in the Middle East, which has seen

several Gulf Arab states start to align with Israel even without any Israeli

concessions to the Palestinians. An Israeli

overreaction might also increase the chances that Hezbollah and its patrons

in Iran will join the fray.

Mobilization

strategies, meanwhile, seek to grab attention, draw recruits, and gather allies

for a terrorist group’s cause. The Islamic State, known as ISIS, did that in

2014, carrying out some basic functions of government in the parts of Iraq and

Syria it conquered to create the appearance of order and also carrying out

gruesome videotaped beheadings of hostages to create an image of

uncompromising, fearsome severity. Seeming to take a page from the ISIS playbook, Hamas has threatened to

kill a hostage each time Israel targets “people who are safe in their homes

without prior warning,” in the words of Abu Obeida, a spokesperson for the

Hamas military wing, the al-Qassam Brigades. Obeida also suggested that the

group would broadcast the executions, probably on social media. Hamas leaders

may be calculating that such ultraviolent spectacles would bring further

attention to their cause and mobilize support—not only among Palestinians but

also among sympathizers and anti-Semitic extremists throughout the region and

worldwide. In the long run, preying on humanity’s basest instincts through

spectacles of dominance and vengeance will cause a global backlash and destroy

Hamas. But like ISIS before it, the group may believe that such tactics will

buttress it in the short term.

The Return Of The Repressed

Israel has limited

strategic options for an opponent that relies on provocation and mobilization.

It seems to have chosen repression, a time-honored but rarely successful

approach to counterterrorism.

An overwhelming

military response can successfully repress a terrorist group. In 2009, the Sri

Lankan army crushed the Liberation Tigers of Tamil

Eelam, an ethnic separatist group of 10,000 to 15,000 members, killing

up to 40,000 civilians, according to the United Nations. That paroxysm of ethnic

cleansing and extrajudicial killings devolved into a gruesome civil war,

trapping Tamil civilians in the violence. Many remain internally displaced,

with thousands of victims unaccounted for. In the 1990s, the Peruvian

government defeated the Shining Path, a

Maoist revolutionary terrorist group, using indiscriminate military force. But

Peruvian democracy suffered: President Alberto Fujimori dissolved Congress and

the judiciary, setting in motion a process that routinized extreme policies and

eventually led to his downfall. (Sendero Luminoso, meanwhile,

survived as a political party.)

Repression has also

been Russia’s preferred counterterrorism strategy. In 1999, when authorities

blamed a series of bombings in Moscow and Volgodonsk

on Chechen terrorists, President Vladimir Putin vowed

to “flush the Chechens down the toilet.” He used the crisis to consolidate his

power. He launched a vicious campaign that leveled the Chechen city of Grozny,

killed at least 25,000 civilians, and displaced hundreds of thousands. Chechen terrorism was significantly diminished

but not eradicated: in 2002, Chechen terrorists took 912 hostages in a Moscow

theater (175 people ultimately died), and two years later murdered 344 people,

mostly children, at an elementary school in North Ossetia.

Repression is a

natural response to terrorism, and countries worldwide have resorted to

repressive means before eventually learning more effective strategies. As a

form of counterterrorism, repression is tough for democracies to sustain, and

it usually does not destroy its target. Repression also exacts an

enormous cost in money, casualties, and individual rights and works best in

places where the members of terrorist groups can be separated from the broader

population. Using overwhelming force tends to disperse the threat to

neighboring regions. So when Israeli government officials speak of destroying

Hamas “at any cost,” one wonders whether they are considering not only the

certain costs to Hamas, Gazan civilians, the hostages, Palestinians in the West

Bank, and Arab Israelis but also the potential long-term costs to regional

stability, Israeli democracy, and Jewish Israelis.

Repression succeeds

under certain conditions, but the situation in Gaza does not meet them. It will

be impossible to kill Hamas leaders and fighters without causing massive

civilian deaths, displacing hundreds of thousands, and immiserating the entire

population of Gaza. These outcomes are already evident. Some 1,900 Gazans have

already died in Israeli retaliatory airstrikes. Meanwhile, Israel has imposed a

siege, cutting off supplies of electricity, food, and water to Gaza with

apparent disregard for the effects on the vast majority of Gazans, who have

nothing to do with Hamas. (“We are fighting human animals, and we act

accordingly,” Gallant remarked by way of justification—employing precisely the

kind of dehumanizing rhetoric that Hamas’s strategy of provocation aims to

generate.)

On October 13, Israel

ordered 1.1 million Gazans to evacuate to the south of the territory or face

the brutal consequences of an Israeli military campaign they might not survive,

thus creating more conducive conditions for repression and risking a full-scale

humanitarian disaster. The only way to leave Gaza is through the Rafah transit

point on the Egyptian-Gazan border. But Israel has recently hit that crossing

with airstrikes, making it difficult for anyone to cross safely or to bring in

humanitarian aid or medical supplies, which are already exhausted.

If thousands more

civilians die due to Israel’s response, Hamas (or whatever group takes its

place) will publicize those deaths to build support and set off another cycle

of violence that occupying Israeli troops will struggle to contain. Israeli

commentators have called this a zero-sum situation: they believe any loss for

Hamas is a gain for Israel. But as the war unfolds, Israel is hurtling toward a

lose-lose outcome.

How To Win By Not Losing

Overwhelming military

oppression in Gaza would backfire, stirring support for resistance and aligning

Israel’s adversaries against it. A more nuanced political strategy would divide

them. Israeli leaders must make clear that their enemies are the 30,000 Hamas

fighters in Gaza, especially the Qassam Brigades, and not the two million other

residents of Gaza. Hamas has claimed that every Israeli is a combatant to

legitimize its barbarity, just as al Qaeda and ISIS did in their West and

Middle East campaigns. Israel must avoid doing the same thing and

make clear that it is explicitly targeting Hamas.

A successful Israeli

military response would use discriminatory force, making it clear through both

statements and actions that Israel’s enemy is Hamas, not the Palestinian

people. The Israeli government should help fleeing Gazans find somewhere to go

by either creating safe zones, enabling the Egyptians, or permitting regional

or international actors to create a humanitarian corridor and then allowing aid

organizations to supply food and water to trapped civilians. Even in the north,

they must avoid targeting Gazan hospitals where the injured cannot be moved.

Hamas will use those people as human shields—and when they do, such barbarity

toward their people will sap the group’s ability to mobilize more comprehensive

support. The Israel Defense Forces will fight street to street; Hamas will not

hold them off for long, regardless.

No one is asking for

a new Israeli-Palestinian peace process now. Still, Israeli leaders must stop

actively encouraging West Bank settlements to expand, a process that has

gradually snuffed out any hope of a two-state solution. Israel must give the

Palestinian Authority a reason to stand aside during this fight; otherwise,

Israel will be flanked by fighting in both Palestinian territories. Israel must

lean on its international partners to urge Iran not to encourage attacks by

Hezbollah. The United States has warned Tehran and the terrorist group not to

attack Israel. It has sent a carrier strike force to the region to deter them

and any other parties from joining the conflict. Steps such as U.S. Secretary

of State Antony Blinken’s tour of six Arab countries and discussions with

Palestinian Authority leader Mahmoud Abbas can help, but only if Israel does

not further inflame its enemies with indiscriminate killing in Gaza.

Finally, the Israelis

must come together politically, not just militarily. Before the attacks,

Netanyahu’s efforts to weaken Israel’s judiciary had divided the public. They

produced pushback among some military reservists and even some senior members

of the security establishment, arguably making the country more vulnerable to

attack. Without a clear endgame, a renewed occupation of Gaza could further

split the country. Netanyahu has created an emergency unity government with one

of his rivals, the former army general Benny Gantz. But Netanyahu has refused

to fully sideline the far-right members of his coalition, suggesting that he is

still unwilling to move past the divisive politics that paralyzed Israel and

possibly invited this Hamas assault. Only a truly unified political leadership

will fortify Israel’s democracy for the complex military operations ahead,

giving it the domestic mandate necessary to build a winning strategy and end

Hamas for good.

For updates click hompage here