By Eric Vandenbroeck

China’s longest lasting dynasty, the Zhou Dynasty lasted from roughly 1000

BC to 221 BC. Initially comparing this with a case study about Rome and France

I traced the evolution of transborder sovereignty over the course of China’s

longest lasting dynasty, the Zhou Dynasty which lasted from roughly 1000 BC to

221 BC. During the course of the Zhou Dynasty as compared with the case studies

about Rome and early Europe, it was shown how feudal

states in China were more autonomous, had no overlapping, cross-cutting

authorities, and had strong territorial markers. And that during the course of

the Zhou Dynasty we see a shift from transbordersovereignty

to absolute sovereignty with the Warring States Period representing a transitional phase to

imperial China. From the age of Confucius onward, the Chinese people

in general and their political thinkers, in particular, began to think about political

matters in terms of the world. And that absolute

sovereignty, as a principle, had existed

prior to the first Qin emperor. The essential structure of

the ideological subsystem at the beginning of the Zhou dynasty was built on a

two-fold distinction. One tenet held the centrality of the king and the Mandate

of Heaven to legitimize his rule. The second tenet held the centrality of law and order

variously derived as the overarching legitimating factor for any given ruler. Thus

ancient China showed us a highly structured feudalism, a territorially bound

state that struggled to develop a bureaucracy to govern it, and a nation rich

in tradition before a state, as

started to be the case during the Qin, could grow powerful enough to govern it.

The Song dynasty (Chinese: 宋朝; pinyin: Sòng cháo; 960–1279) next was an era of Chinese history that

began in 960 and continued until 1279. It was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song

following his usurpation of the throne of Later Zhou, ending the Five Dynasties

and Ten Kingdoms period. The Song often came into conflict with the

contemporary Liao and Western Xia dynasties in the north and was conquered by

the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Song government was the first in world history

to issue banknotes or true paper money nationally and the first Chinese

government to establish a permanent standing navy. This dynasty also saw the

first known use of gunpowder, as well as the first discernment of true north

using a compass.

But while thus the end of Northern Song and the beginning of Southern

Song Dynasty is considered a high point of Chinese innovation in

science and technology, it is also where we will discover, lay the roots of

Chinese Nationalism or the idea Han cosmopolitanism.

Today we know that along

the East-West axis of China, demonstrated a general pattern of

isolation-by-distance among Han Chinese, and reported unique regional signals

of admixture, such as European influences among the Northwestern provinces of

China.

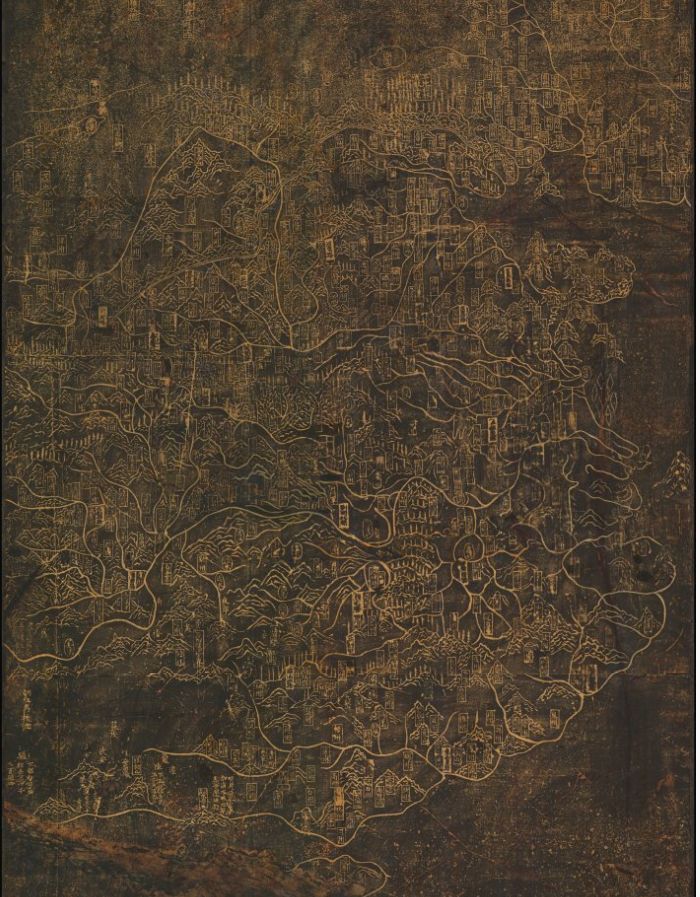

A 12th century Hua Yi Tu map covers China during the Song Dynasty.1 The

map depicts mountains, rivers, lakes, as well as more than 400 administrative

place names of China. It includes Korea in the west of Pamier

area, from north to the Great Wall, northeast to Heilongjiang region, to the

south of Hainan Island. The texts arranged around the edges of the graphic part

of the map provides information from historical and other sources briefly

explaining markers such as the Great Wall, the size of the empire, and the

states to the west. The stele containing the carved map is thought to be stored

at the Stele Forest in Xian, but is not displayed due to the political

sensitivity of not depicting the island of Taiwan on it, which can be

interpreted as Taiwan not belonging to China at the time of the map's

production.

The map was striking for several reasons, first and foremost its chief

objective – to inspire irredentist passions. Historians typically associate

irredentism of this sort more with the world of the nineteenth and twentieth

centuries than with twelfth-century China. To be sure, Huang himself may have

imagined a future emperor as the chief viewer of his map. A few decades later,

however, in 1247, an official serving in Suzhou had the map and colophon carved

onto a stele – a stele that stands to this day – “in

order to maintain its transmission.” Once on a stele,

the map and its message would have circulated via rubbings to a broader

audience. Another noteworthy feature of the map was the colophon's particular

emphasis on the territorial claim to the Sixteen Prefectures. Unlike the lands

south of the Yellow River seized by the Jurchens, the Sixteen Prefectures – a

region straddling the northern extremity of the North China Plain – was lost to

the Khitans before the founding of the Song. Asking

to have it “returned to our possession” made sense only insofar as the pronoun

“our” referred not merely to the Song state, but rather to a political entity

that transcended dynasties.

The East Asian World Order

Throughout the period under consideration here, Song China coexisted

with several other important East Asian powers, though not all were of equal

concern to Song policymakers. Contact with states in Korea, Japan, and maritime

Southeast Asia was generally limited to trade (often under the guise of tribute

missions), although, due to its shared border with the Khitan

Liao empire – to be examined in some detail below – the Koryō

Kingdom in Korea would come to play an important ancillary role in Song– Liao

relations. To the south, the two most significant states, the Kingdom of Dali

(937– 1253) in Yunnan and the Ly Dynasty (1009– 1225) in Vietnam, remained

separated from China by a buffer region inhabited by autonomous tribes. During

the Song, Chinese colonists spread relentlessly southward, recurrently

provoking armed opposition from tribal groups in their path. Some of these

tribes were held under a “haltered-and-bridled” system, whereby in exchange for

maintaining their de facto independence their chiefs accepted Chinese

bureaucratic titles and other symbols of subordination to the Chinese throne. 2

Contact with Dali, however, was restricted to an important trade that supplied

horses for Song China’s northern campaigns.3 Military confrontations with

Vietnam broke out only after the destruction of one of the intervening tribal

regimes in the late eleventh century.4 In sum, due to the relatively limited

scale of direct political interaction or military confrontation, the southern

and maritime frontiers were never the main focus of attention at the Song

court.

By contrast, the steppe-based regimes on the northern and northwestern

frontiers were understood to be an immediate threat to the Song’s very

existence. In the words of one mid-eleventh-century statesman, in response to a

policy question from the emperor regarding unrest in the south, “How are these

trifles worth exhausting imperial power and intruding on the emperor’s

concerns? … The most significant border issues lie in the west and the north!”5

Indeed, in the 1120s, the Jurchens, precursors to the Manchus of the Qing

Dynasty, would sweep down from Manchuria to conquer the whole of North China,

forcing the Song court to flee southward and establish a new regime – the

Southern Song – based beyond the Yangzi River. In the next century, the Mongols

descended from the Eurasian steppe, first destroying the Jin Dynasty (1113–

1234) of the Jurchens, and then overrunning the Song four decades later. But

long before the Jurchens and Mongols arrived on the scene, China already faced

two major steppe powers.

To the northwest were the Tanguts and their state of Xi (Western) Xia

(982– 1227). In the early decades of the Song Dynasty, the court paid little

attention to this state, which was generally seen as posing no substantial

military threat. A peace agreement in 1006 ushered in three decades of good

relations. By the 1030s, however, the Xia Kingdom had expanded significantly,

mostly by seizing territories further west from various Uighur and Tibetan

tribes and chieftaincies. The first significant war with China broke out in

1038, when the Tangut ruler had gained enough confidence to proclaim himself

emperor, thereby undermining the symbolic superiority of the Chinese monarch.

During the subsequent years of warfare, the Tangut regime amply demonstrated

its military might. After a temporary peace treaty in 1044, hostilities broke

out again two decades later following repeated Tangut incursions – exacerbated

by the military adventurism of Song frontier commanders, and the simultaneous

disintegration of Song China’s Tibetan client state based in Hehuang (in modern-day Qinghai). Thereafter, the Song

emperor Shenzong (r. 1067– 85), guided by his hawkish

advisors, embarked on a series of large-scale military campaigns. Over the next

sixty years, under Shenzong and his successors, this

irredentist agenda fueled repeated wars, leading to crippling losses of men and

resources on both sides. Nevertheless, by the 1120s, Song China had managed to

capture large swathes of Tangut territory, while simultaneously annexing

Hehuang.6

The Northern Song’s most formidable neighbor, however, was undoubtedly

the Liao empire (916– 1122), established by nomadic Khitans

in the early tenth century. Even before the founding of the Song, during the

Later Jin Dynasty (936– 47), the Liao had obtained sixteen prefectures in

northern Hebei and Hedong that had been traditionally

under the control of Chinese regimes. The result was an unusual geopolitical

situation, whereby the Song– Liao border cut directly across the North China

Plain. Song China’s second emperor, Taizong (r. 976–

98), twice attempted to recapture this territory – in 979 and again in 986 –

but both military campaigns failed miserably. The next two decades saw nearly

continuous border skirmishes, culminating in a massive Liao invasion in 1004

that brought Khitan troops to within a hundred miles

of the Song capital of Kaifeng. The Khitan invasion

was halted only after the Song emperor Zhenzong (r.

998– 1023) personally led his troops into battle. At this point, realizing that

their army was precariously over-extended, the Khitans

agreed to a peace settlement. Thus, in January 1005, Zhenzong

and his Liao counterpart exchanged oath letters at Chanyuan

on the northern banks of the Yellow River.7 Thereafter, there were two

significant confrontations, first in 1042, when the Khitans

took advantage of the Song– Xia war to claim ten counties in Hebei that they

had controlled prior to the founding of the Song Dynasty; and second in the

mid-1070s, when the Song and Liao courts had a heated disagreement over the

proper course of the border in Hedong to the west.

But both disputes were resolved diplomatically. Peaceful relations broke down

only in the late 1110s when Song China embarked on a misguided alliance with

the Jurchens against the Liao, an alliance that went sour and led both to the

fall of the Khitan state and to the Song’s loss of

all of North China.

The Chanyuan

peace

Two important consequences of the Chanyuan

peace are worth stressing. First, the many years of diplomatic exchanges,

spanning the eleventh century and lasting over a hundred years, spurred a new

form of cosmopolitanism, whereby Song political elites acquired firsthand

experiences traveling into the steppe and socializing with Liao diplomats.

Second, the unusual geopolitical configuration of the Song– Liao border brought

a large ethnically Han population under the control of the Liao state. These

Han people were recruited in large numbers to staff the Liao civil

administration at all levels, even as the Liao state sought actively to

preserve the sharp ethnic divide between them and the Liao Khitans.

The significant presence of ethnic Chinese in influential governmental

positions undoubtedly contributed to Liao's unique relationship with Song

China.

The century of peace between Song and Liao also played a critical role

in the evolution of the structures and norms of traditional Chinese diplomacy.

An influential thesis, put forward three decades ago in a volume edited by

Morris Rossabi, emphasized the pragmatism and innovation evident in Song

China's relationship with Liao. According to Rossabi, the diplomatic parity

that existed between the two states – whereby the monarchs of both Song and

Liao recognized each other as an “emperor” equal in status – discredited once

and for all the notion of a “Chinese world order,” formulated by John King

Fairbank, an interpretation holding that external regimes could interact with

China only on China's terms, by accepting their subordination and offering

regular tribute to the Chinese ruler. To the extent that Song– Liao relations

took on certain characteristics of the post-eighteenth-century European state

system, Rossabi's thesis seems to underline yet another area in which Song

China was ahead of its time.8

It is possible to expand on the implications of Song– Liao diplomacy by

exploring the cultural dimensions of inter-state systems. The contemporary

world order does not, of course, constitute the only legitimate mode of

inter-state relations. One might argue that a maximally rational system of

inter-state relations is any system in which all participants generally agree

to a single set of rules.9 These rules may well develop over time as different

regimes, perhaps with very different linguistic and cultural backgrounds, are

compelled to find ways to coexist. Prior to the arrival in East Asia of large

numbers of Europeans,10 those East Asian regimes that came into frequent

contact with one another had already developed their own set of arrangements

for inter-state interactions, arrangements that I refer to here as the “East

Asian world order.” Such an understanding differs from Fairbank's original

thesis. First, it does not assume that China had exclusive control over how the

inter-state system developed. Second, it does not consider inter-state dynamics

to have been fixed and unchanging. As is true of the modern world order, the

East Asian world order was a constantly evolving system, developing at the

interface between the political cultures of several coexisting East Asian

states.11 Indeed, as we shall see below, Song foreign relations contained

elements of earlier inter-state dynamics, even as they would also include

important new developments.

How then can one characterize the East Asian world order as it existed

by the beginning of the Song period? In the first place, it was clearly

hierarchical. Not surprisingly, the hierarchy in question generally reflected

the relative political and military might of the various constituent states. It

was made explicit in the language of diplomatic correspondence, in the titles

given to envoys, in the “appointment” edicts sent to the rulers of subordinate

states, in the choice of whose calendar was used in dating documents, and, of

course, in the symbolic tribute offered by smaller states to their larger

neighbors. Because it was largely expressed symbolically, hierarchy did not

preclude pragmatic negotiations between nominally unequal regimes. In fact, in

some sense, it expanded the flexibility of diplomacy, allowing one state to

accept a putative subordination as a concession for some other gain that it

might consider more valuable. In general, it was unusual for any two states to

acknowledge equality, but the Song– Liao example makes it clear that parity was

not impossible. Though tributary states were expected to subordinate themselves

to only one other state, instances of “multiple sovereignty” – whereby one

small regime simultaneously offered tribute to and recognized the suzerainty of

more than one larger neighboring state – were probably quite common.12

In the second place, communication between regimes within the East Asian

inter-state system was generally embodied in formal missives written in

classical Chinese, dispatched to the court of a neighboring state via an

ambassador and his retinue. With no tradition of permanent diplomatic

representation, premodern East Asian regimes relied on traveling embassies for

inter-state communication. Ambassadors were dispatched to neighboring states

bearing “state letters” or other types of diplomatic correspondence,13 along

with a large number of valuable gifts.14 These embassies did not stay abroad

long, returning home soon after delivery of the letter. Thus, there were no

ambassadors based permanently or semi-permanently at foreign capitals. A

variety of additional protocols developed over time, including, for example,

restrictions on the sending of envoys whose given name violated the “taboo”

name of the host country's ruler.15

The Chanyuan Oath seems to have spurred

further developments in this East Asian inter-state system. The oath letters

exchanged between the Song and Liao emperors provided the language used in

subsequent inter-state agreements, notably between the Song and the Jin, and

between the Song and the Xia.16 There is also evidence that, in the century

after Chanyuan, agreements between states were

increasingly seen both as contractual in nature and as built upon an

accumulation of precedents. But it was only in the late eleventh century that

the Song central government began insisting upon the consistent archiving of

all past agreements. These archives provided the late Northern Song government

with what one might call “archival authority.” After convincing its neighbors

to accept the principle that countries should abide by past agreements, the

Song regime began to benefit directly from the relative comprehensiveness of

its own archives. Its ability to produce agreements from a past generation

helped it maintain a degree of hegemony on the world stage.

In addition, the large number of embassy missions traveling between Song

and Liao over the course of the eleventh and early twelfth centuries, brought

about the routinization of procedures governing how foreign ambassadors were

accompanied from the border to the capital, how they were received at court,

the seating arrangements at diplomatic banquets, and the type and number of

gifts exchanged.17 One can contrast this routinization with the much more ad

hoc diplomatic ceremonies of earlier times, such as the late eighth-century

oath ceremony between Tibet and Tang China.18

During the same period, several East Asian regimes seemed to move toward

a common model for legitimating rulership, evident in the circulation and

widespread influence of certain specific texts. Although the “Confucian”

classics remained popular throughout East Asia, new works on political

philosophy gained currency in the eleventh century, notably the early

eighth-century Zhenguan zhengyao

(The Essentials of Government of the Zhenguan Era).

Perhaps deemed more practical and up-to-date, this text – which provided advice

on statecraft in the form of dialogues between the early Tang emperor Taizong (r. 626– 49) and his ministers – became influential

at the Khitan, Tangut, Koryō,

Jurchen, and Mongol courts.19

Diplomatic cosmopolitanism

Finally, the Song– Liao border demarcation prompted by the Chanyuan Oath led to a systematization of techniques for

designating inter-state boundaries. Clearly, for the demarcation to be

effective, the frontier had to be marked onto the landscape in a way that was

recognizable by neighboring populations. The fact that a particular combination

of trenches and tumuli was used to indicate both the Song– Liao and the Song–

Xia frontiers suggests that the populations of multiple states had come to

accept and recognize this particular means of territorial demarcation.

How did the eleventh-century multi-state system influence the emerging

Chinese sense of self? In response to this question, most historians of the

period focus on the combined military threat of the Tanguts and the Khitans, which are said to have compelled the Song Chinese

to reimagine their place in the world. But the annals of Chinese history are

filled with instances of great nomadic confederations developing on the

Eurasian steppe, threatening China's existence, and even – on occasion –

invading the Chinese heartland.20 The mere existence of powerful neighbors on

the frontiers, then, is insufficient to explain developments that date

specifically to the eleventh century. Moreover, Northern Song policymakers were

not nearly as concerned about the threat of a northern invasion as has

sometimes been imagined. The impact on Chinese mentalities of the new East

Asian world order of the eleventh century was complex. The military threat from

the north did play a role in forcing Song statesmen to reassess the limits of

imperial power, but so did the formal recognition of a second emperor – the

ruler of Liao – within that world order. Perhaps even more significant, was the

diplomatic “cosmopolitanism” emerging in the era, a cosmopolitanism that

involved both new forms of sociability and new travel experiences to lands

beyond the frontier. This and more we explain in the next part.

Case study about the Qin Empire

1. For images of Huang's map, see Cao Wanru et al. (eds.), Zhongguo gudai ditu ji, pls. 70– 72; for a study and transcription of the

colophon, see Qian and Yao, “Dili tu bei.”

2. Von Glahn, Country of Streams and Grottoes; Von Glahn, “Conquest of

Hunan”; An Guolou, Songchao

zhoubian minzu, 54– 62.

3. Yang Bin, Between Winds and Clouds, chap. 3, paras. 59– 69.

4. J. Anderson, “Treacherous Factions.”

5. Zeng Zaozhuang and Liu Lin (eds.). Quan

Song wen. Shanghai cishu chubanshe,

2006. 38: 24.

6. For more on Song– Xia relations, see Dunnell, “Hsi Hsia,” esp. 168–

97; P. J. Smith, “Irredentism as Political Capital”; P. J. Smith, “Crisis in

the Literati State”; Lamouroux, “Militaires

et bureaucrates”; Li Huarui,

Song Xia guanxi shi.

7. For a good summary of Song– Liao relations up until the Oath of Chanyuan, see Lau and Huang, “Founding and Consolidation of

the Sung Dynasty,” 247– 51, 262– 70.

8. Rossabi (ed.), China Among Equals; Fairbank (ed.), Chinese World

Order.

9. Though such an ideal-type inter-state system is stable in the sense

that all participants agree to the rules, stability did not preclude the

possibility of war. Throughout the late imperial period, Chinese regimes fought

wars with their neighbors to the north and to the south. The violent conquests

of Yunnan, Guizhou, and other parts of the south should not be treated as

“internal” conflicts – as a nationalist might insist – but rather as wars of

conquest against established neighboring polities.

10. The earliest Europeans arriving in East Asia were willing to

integrate into the East Asian inter-state system. Thus, e.g., when the

Portuguese reached Southeast Asia, they agreed to receive the tribute that the

Malaysian sultan had once sent to China. See Santos Alves, “Voix de la prophétie,” 43.

11. On the role of non-Chinese regimes in

defining East Asian diplomatic practices during the Tang, see Skaff, Sui-Tang

China; Wang Zhenping, Tang China in Multi-Polar Asia.

12. For a discussion of “multiple sovereignty” in Southeast Asia, where

it seems to have been a common practice, see Thongchai, Siam Mapped, 81– 94. A

comparison of Tibetan and Chinese chronicles reveals that, already in the

eighth century, the Yunnan-based state of Nanzhao simultaneously accepted the

suzerainty of both the Tang and Tibet (unbeknownst to the Chinese). See Backus,

Nan-chao Kingdom, 40– 45.

13. Franke, “Sung Embassies,” 119– 21. In fact, the term “state letter”

(guoshu or guoxin) was only

used for Song– Liao correspondence; “edict” or “decree” was used in the case of

letters sent to Koryō and the Xia, which were not

treated by the Song as diplomatic equals.

14. Ibid., 130– 31.

15. E.g., the powerful Song minister Sima Guang (1019– 86) could not

serve as ambassador to Liao because his given name coincided with part of the

name of the second Liao emperor, Yelü Deguang. See QSW 55: 123.

16. Franke, “Sung Embassies,” 119. E.g., the oaths with Liao, Jin, and

Xia all included nearly verbatim clauses regarding the repatriation of

cross-border fugitives. See XCB 58.1299; Yuwen Maozhao,

Da Jinguo zhi jiaozheng, 37.527– 28; XCB 80.2022.

17. For descriptions of proper ritual protocols for the reception of

envoys and of the choreography of diplomatic visits to the Song and Liao

courts, see SS 119.2804– 10, 328.10565; Li Xinchuan, Jianyan yilai chaoye

zaji, vol. 1, 3.97– 98; Ye Longli,

Qidan guo zhi, 21.200– 03; Zeng Zaozhuang

and Liu Lin (eds.). Quan Song wen. Shanghai cishu chubanshe, 2006 (henceforth QSW) 27: 104– 06; QSW 50: 228–

37.

18. To sanctify the oath, the Tibetans and Chinese had initially agreed

to sacrifice an ox and a horse, respectively. But the Chinese representative

had second thoughts “as Chinese cannot farm without oxen, and Tibetans cannot

travel without horses.” He proposed sacrificing sheep, pigs, and dogs in their

stead. His Tibetan counterpart agreed to the idea, but no pigs were available,

so the diplomats had once more to change plans. Eventually, the Tibetans

settled on a ram, and the Chinese on a sheep and a dog. See Liu Xu et al. Jiu

Tang shu. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju,

1975. 196b. 5247.

19. Franke and Twitchett, “Introduction,” 33, 34;

Franke, “Chinese Historiography,” 20, 21, 22; Bol, “Seeking Common Ground,”

503; Lee, Sourcebook, 1: 273– 74.

20. For a history of sino-steppe encounters

over the longue durée, see Barfield, Perilous Frontier.

For updates

click homepage here