By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

When humanity almost got wiped out

There is no way out

of the imagined order,’ writes Yuval Noah Harari in his book Sapiens.

From human life 70,000

years ago to the current day, human cultures have not improved over time, as

many experts believe, and humanity is prospering today because we are so

numerous and advanced as a species. As our societies have become more

complicated, he believes people have become continually unhappier. The more

powerful we grow, the more unpleasant life becomes for other creatures.

He is not alone in

reaching this conclusion. Most people who write history on a grand scale seem

to have decided that, as a species, we are well and truly stuck, and there is

really no escape from the institutional cages we’ve made for ourselves. Once again

echoing Rousseau, Harari seems to have captured the prevailing mood.1

Little discussed is

that during the Cretaceous Period, a comet six miles wide, taller than Mount

Everest and traveling at a hundred times the speed of a jet plane, targeted the

earth.2

Some 66 million years

ago, a six-mile wide asteroid slammed into the ocean off the coast of Mexico’s

Yucatán Peninsula, carving out a 110-mile wide crater known as Chicxulub. In an

instant, the trajectory

of life on Earth was forever changed. The impact kicked off wildfires and tsunamis across

thousands of miles. Then swings in global climate - a dramatic period of

cooling followed by a long period of warming - ushered in the extinction of

some 75 percent of all species, including the non-avian.

The dominant land

animals on earth before the comet's arrival were dinosaurs.3 Right up until

that day, the future of the dinosaurs looked pretty bright. They were at the

top of the food chain, without equal, and there were no signs of that changing.

We accomplished the

extinction of other animal species through a combination of hunting and turning

half of the earth’s dry surface into farms.3 Of course, domesticated animals,

are a different story. Today, just a handful of species - cattle, pigs, sheep,

goats, and Homo sapiens - make up 97 percent of the land animal biomass on

earth. Homo sapiens continues to exterminate other species, except for those

destined for our table. The current extinction rate for all species is now more

than 100 times higher than before. The global population of vertebrates has

declined by 52 percent from 1970 to 2010.4One-quarter of all mammals and 10

percent of all plant species today are threatened with extinction.4 All these

species, including the other humans, have vanished into the mists of history.

The 99 percent of all species that once lived and are now dead are not around

to contemplate the prospects for their survival. At one time, the future must

have seemed bright for many of these now-extinct species. If given to contemplating

their fate, the dinosaurs were probably looking forward to dominating the

planet for many millions of years to come. Like us, they might have expected to

survive because they had always done so in the past. But if a poll were taken

of all species, the survivors and non-survivors, on the question of whether the

earth is a hospitable place for life, about 99 percent would vote no. The only

ones likely to vote yes - the 1 percent - are those that happened to survive.

We are fortunate that

a small comet passed by us in 1736. We are equally lucky that a large one

struck the earth 6 million years ago.

During the Cretaceous

Period, a comet six miles wide, taller than Mount Everest and traveling at a

hundred times the speed of a jet plane, targeted the earth.5 The comet (or

asteroid; exactly which is still debated) entered the atmosphere, created a

vacuum that sucked up hundreds of millions of tons of dirt into the clouds, and

then smashed into the Yucatan Peninsula with the energy equivalent of a billion

atom bombs, leaving a hole in the ground twenty-five miles deep and more than

one hundred miles wide. The resulting fires circled most of the planet, burning

forests and plant life, instantly roasting any animal in its path into charred

ash. Within minutes, the “ejecta” - liquefied rocks sent into the atmosphere

from what is now Mexico - rained down upon the planet, and a hail of lethal

projectiles shredded animals not previously incinerated into little pieces of

bone and flesh. The shock to the earth’s crust set off magnitude 12 earthquakes

around the globe that shallowed up parts of whole continents, ignited massive

volcanic eruptions that covered millions of square miles of land in molten

lava, and triggered tsunamis that flushed sea life hundreds of miles inland.

Ninety percent of the biomass of the earth was suddenly gone.6

And then it got cold

The ejecta and dirt

in the clouds smoke from planetary-scale forest fires, and ash from volcanic

eruptions blocked the sun’s rays. Global temperatures may have plummeted as

much as fifty degrees over land and thirty-six degrees over the oceans. Less

than 1 percent of sunlight reached the planet's surface, halting

photosynthesis. Many creatures still alive soon starved to death on frozen

landscapes.7 The earth had gone from fireball to snowball.

Bad News for Dinosaurs: Good News for Us

The dominant land

animals on earth before the comet's arrival were dinosaurs.8 Right up until

that day, the future of the dinosaurs looked pretty bright. They were at the

top of the food chain, without equal, and there were no signs of that changing.

Nothing indicated that the planet was anything other than a habitat

particularly well suited to a dinosaur’s way of life.

If Homo sapiens had

been alive when the comet struck, we would not have made it.9 But some animals

did survive. A few tiny dinosaurs with wings were not killed. Maybe they were

nesting in caves on that fateful day, or flight allowed them to scour the earth

for food, such as seeds or the roasted animal carcasses that littered the

earth. In any case, these small, winged dinosaurs managed to find food and

evolved to become today’s birds. Many species of fish, protected by the vast,

deep oceans, also survived. And a few small mammals, about the size of rodents,

somehow lived through this global holocaust. The descendants of these rat-like

creatures would evolve to write books about dinosaurs and survivor bias.10

The king of the

dinosaurs was Tyrannosaurus rex or T. rex for short. Some forty feet long,

weighing seven or eight tons, T. rex was one of the largest meat-eating animals

ever to walk the face of the earth.11 Its skull was five feet in length with

eyes the size of grapefruits and a jawbone lined with fifty or so knife-sharp

teeth.12 Unlike us, T. rex could regrow broken teeth, which was helpful given

its table manners.13 The king of the dinosaurs benefited from exceptional

senses: binocular vision thirteen times better than modern humans, and the

ability to hear and smell other animals at great distances.14 Above all, T. rex

was thought to have been among the smartest animals around at that time.15

When a large comet

struck the earth, this was bad news for dinosaurs but good news for us. Most

believe that Homo sapiens could not have coexisted with such carnivorous

beasts. We probably would have been a tasty appetizer: a tall, moderately

sized, fleshy mammal who ran upright (easily spotted) and could not run that

fast (easily caught). We can be thankful our ancestors were small,

ground-hugging, sub-snack-sized rodents, not worth pursuing. Probably our

ancestors’ main concern was not to get accidentally stepped on. We have not

discovered any preserved T. rex or other dinosaur brains, so the best evidence

of intelligence is the encephalization quotient (EQ), the ratio of brain mass

to body size. As an indication of intelligence, EQ has drawbacks because the

size of the individual components of the brain is important. For example, the

size of the neocortex matters more than that of the limbic system as an

indicator of intelligence. Nevertheless, EQ is roughly correlated with IQ. T.

rex had an EQ of 2.0 to 2.4.. That is about twice that of a dog, more than a

chimpanzee, and about one-third of a modern adult human.16

If T. rex had

survived, we can only speculate how far another 65 million years of brain

evolution would have taken their species. When humans first evolved, our

intelligence was about the same as that of T. rex. During six million years of

human evolution, our brain size has almost tripled: Our EQ started at 2.5 and

eventually rose to 5.8.1719 But T. rex would have had a 65-million-year head

start on brain evolution. Even if Homo sapiens somehow could have found a way

to coexist with T. rex, it is unclear which would have become the more

intelligent and dominant species.

A Planet Better at Preserving Fossils than Life

Sixty-five million

years ago was not the first time most living organisms on earth were

exterminated. In fact, the space rock that killed the large dinosaurs was the

most recent of five mass extinctions, defined as events in which most species

on earth perished.

The “big five” mass

extinctions and the percentage of species lost were:

• Ordovician: 444

million years ago (mya), 86 percent

• Devonian: 375 mya,

75 percent

• Permian: 251 mya,

96 percent

• Triassic: 200 mya,

80 percent

• Cretaceous: 65 mya,

75 percent

If we had been around

during any of those five mass extinction events, we could not have survived. We

are fortunate not to have been alive during the first 95 percent of the earth’s

4.5-billion-year history.

In particular, the

Permian mass extinction, known as the Great Dying, was a close call for all

life on earth. A dramatic global rise in temperatures due to volcanic eruptions

dumping massive amounts of CO2 into the skies baked to death almost every land species.

Oceans turned acidic, burning through the gills and shells of most sea life. If

all life had ended, we don’t know how long it would have taken for it to

restart, if ever. Even if it had, we don’t know how much time would have passed

before life once again reached the Permian stage of evolution. The evolutionary

climb to the heights of Permian life took over four billion years after the

earth formed. Hence, life might not have restarted, or evolution could have

followed a different path. It is doubtful that any other path would have taken

the same millions of twists and turns that yielded. Homo sapiens. We are lucky

descendants of the fortunate small percentage of all species that have survived

these mass extinctions.

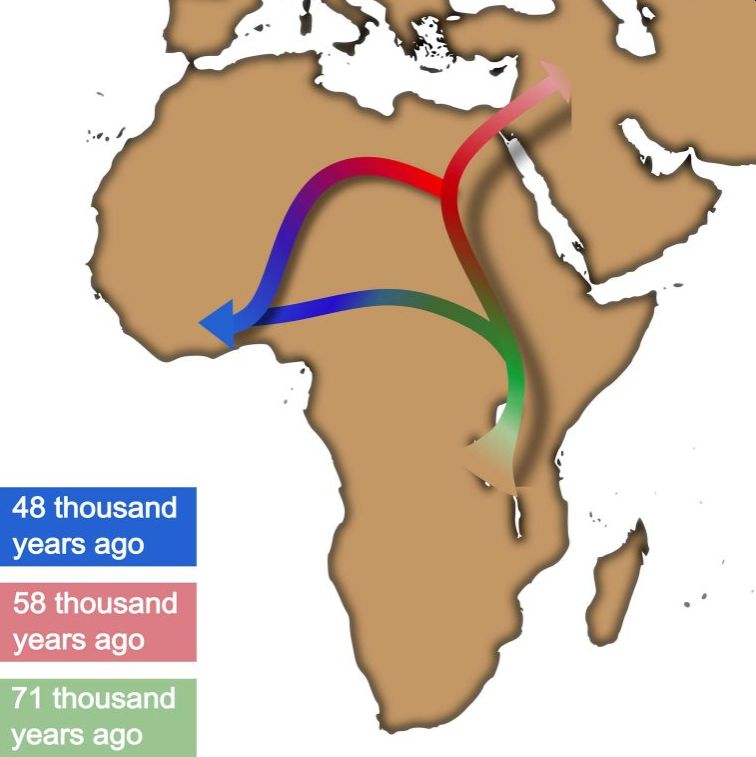

Homo sapiens has

existed as a distinct species for more than 200,000 years. Despite that,

modern-day humans, as demonstrated by DNA evidence, evolved from a group of

common ancestors who lived just seventy thousand years ago.17 After numbering

perhaps hundreds of thousands of individuals at one time, the number of Homo

sapiens fell to as low as several thousand individuals during this period.18

Such a substantial fall in numbers risked the extinction of our species: A

population of merely thousands provides insufficient genetic variation for

natural selection to adapt to environmental change and can lead to

life-threatening genetic deformities from inbreeding.

The causes of this

“bottleneck” in the Homo sapiens population are still debated. The most likely

explanation is that during this time, a volcano, whose caldera today is Lake

Toba in Sumatra, Indonesia, erupted in the largest explosion on earth in the past

two million years.19 The Toba eruption spit ash into the skies that blocked out

the sun’s rays, cooling the planet for more than a thousand years. However,

some have argued the impact on the climate of equatorial Africa, where most

Homo sapiens lived, was not significant.20 Other reasons for the population

bottleneck could be that Homo sapiens were outnumbered by other humans, such as

the Neanderthals, and may have suffered devastating attacks from these

competing human species. Diseases could have also played a role, but

determining the presence of pathogens from ancient skeletal remains is

challenging. Or maybe it was some combination of all the above. Regardless,

Homo sapiens barely survived, passing through a tight population bottleneck

that could have easily led to our extinction.

As survivors, we tend

to believe that the survival of our species was likely, even inevitable. This

is natural. We survived the journey, so we are inclined to conclude that the

journey must not have been perilous. But that fails to account for survivor bias.

The path we took might have been one of the few that did not literally

dead-end.

What we do know is

that most species don’t make it. Ninety-nine percent of all species that once

lived on the earth is gone.21 The vast majority of species on our planet have

lasted from one to ten million years.22 Mammals like us are particularly vulnerable,

surviving only about a million years on average.23 Compared with many other

species, humans have a larger mass, which requires more energy when we hunt for

food - and offers more food when hunted. Our warmblood demands reliable

nutrients to maintain a constant internal body temperature. Our reproductive

cycle has a high infant mortality rate (and maternal mortality rate), and we

birth helpless infants completely dependent on adults for survival. These

vulnerabilities are exacerbated by extended adolescence and, therefore a

greater risk of death from predators. In addition, lower birth rates constrain

our ability to adapt to a changing world through natural selection. Homo

sapiens can procreate about once a year, but cockroaches give birth monthly. Some

bacteria divide into new cells every twenty minutes.

The primary reason

species don’t last is because the earth’s physical environment constantly

changes. For all but a few species, the speed of that change eventually outruns

the pace of adaptation. Charles Darwin called this series of adaptations

“evolution,” which he defined as “descent with modification.” But the earth’s

physical environment changes faster than just about any organism can adapt.24

Sometimes the change in the environment is gradual, such as an ice age, and

other times sudden and violent, like a comet strike, a massive earthquake, or a

volcanic eruption.

In any case, the

earth is better at preserving fossils than life. Despite all this, Homo sapiens

has survived and flourished. We dominate the landmasses of the earth from

soaring mountains freezing in the clouds to tropical islands baking in the sun.

We are the most intelligent species that has ever lived, as complex, symbolic

language gives us the amazing ability to share knowledge with billions of

fellow humans and pass on what we have learned to subsequent generations. In

the next hundred years, we may even extend that domination to the planets

whirling around our sun.

But our journey to

today’s world was actually quite perilous. Some fifty thousand years ago at

least five human species - Homo Denisova, Homo Floresiensis, Homo Naledi, Homo

Neanderthalensis, and Homo Sapiens - coexisted on earth.25 Our species is the

only survivor, the last humans.

Two Enter, One Leaves

Homo sapiens first

appeared in northern Africa around 200,000 BC, the descendants of an early

human species, Homo erectus. Sometime around 120,000 BC, Homo sapiens started

trickling up into Europe, and then a large wave migrated north about 50,000 BC.

There, we encountered Homo neanderthalensis, more

commonly known as the Neanderthals.

Neanderthals were the

most dominant human species at that time, outnumbering all others combined.26

Neanderthals had left Africa much earlier, about 800,000 BC, and moved up into

Europe. By 400,000 BC, Neanderthals were spread throughout Europe and Asia.

Named after the first

specimen found in 1856 by miners in the Neander Valley of Germany, Neanderthals

shared many anatomical and cultural characteristics of Homo sapiens.

Neanderthals were comparable in height, although much heavier in the body, with

stronger and thicker arms and legs, a protruding jaw, and a thick-walled skull

that rode on top of broad shoulders. Homo sapiens and Neanderthals were equally

advanced. Neanderthal brains were as large as those of Homo sapiens,27 and like

Homo sapiens, Neanderthals had language skills.3035 Both species shaped stone

tools, crafted jewelry, painted cave walls, buried their dead, and lived on

comparable diets.3136 Although physically imposing, Neanderthals in other

respects were not that different from modern Homo sapiens. It has been said

that a Neanderthal on a New York City subway would go unnoticed “provided that

he was bathed, shaved, and dressed in modern clothing.”28

Within thousands of

years of Homo sapiens arriving in Europe, Neanderthals died out, followed by

the extinction of the other human species around the globe.29 The cause of such

a rapid extinction of all humans on earth except for Homo sapiens is unknown.

However, archaeologists have put forward several explanations. The most

commonly accepted theory is that we slaughtered them, or what has become

quaintly known as the Replacement Theory.30

As Homo sapiens moved

into the Neanderthal territory, the frequency of violent interactions likely

increased. There are indications that Homo sapiens had better language

abilities than other human species, although our language skills at that time

would still have been primitive and limited.31Consistent with an ability to

better coordinate and communicate, Homo sapiens might have been more cunning

warriors. It appears many Neanderthal men met an unnatural demise. This theory

is supported by Neanderthal male skeletal remains that evidence skulls pierced

by arrowheads or foreheads caved in by rocks. One survey of male Neanderthal

skeletons showed that 40 percent suffered traumatic head injuries.32 There is

also evidence of widespread cannibalism. Neanderthal skulls were often broken

in places that would facilitate the extraction of juicy brain matter, and long

bones were shattered in ways to ease the scooping of moist bone marrow.35

Homo sapiens also

bred with Neanderthals. DNA evidence confirms that Homo sapiens carry genomes from

Neanderthals that range from 1.5 percent in Europeans to 2.1 percent in

Asians.36 Homo sapiens men may have killed Neanderthal men to access

Neanderthal women.37 Given the small bands of hunter-gatherers in which humans

traveled at that time, interbreeding within a group of forty or fifty

individuals could produce genetic anomalies. Homo sapiens men who reproduced

with Neanderthal women gave their offspring an evolutionary advantage.

An alternative

explanation is that Homo sapiens were better hunters, and eventually the

Neanderthals starved to death. It is not clear why that would be the case:

Neanderthals were physically stronger and had established themselves in Europe

and Asia long before us. Another theory is we drove Neanderthals to extinction

because we domesticated wolves (today’s dogs) for hunting and the Neanderthals

didn’t.3840 It is difficult to know just how important dogs were to food

gathering or keeping watch for predators. Still, it seems unlikely that pets -

even working pets - are mainly responsible for the extinction of the

Neanderthals. Yet another theory is that Homo sapiens infected Neanderthals

with lethal diseases we carried within us from Africa. Because the Neanderthals

left Africa hundreds of thousands of years before us, they may have lost

immunity to African pathogens.3941 This would be consistent with other mass

human genocides, such as when Europeans arrived in the New World. However,

particular diseases are difficult to detect in fossils, so there is no direct

evidence of the “disease out of Africa” theory.

Based on what is

known recently, the extinction of the Neanderthals was most likely due to Homo

sapiens slaughtering Neanderthal men and capturing Neanderthal women. With the

Neanderthals out of the way, we could have readily vanquished the remaining less-numerous

human species employing a similar strategy. However, the Neanderthals could

have just as easily won this interspecies battle for survival. In fact, given

their vastly greater numbers and far superior physical strength, Neanderthals

probably were the odds-on favorite. And then Neanderthals would have been the

ones writing books about those primitive, now-extinct Homo sapiens.

Furthermore, we did

not just kill off other humans. After vanquishing our nearest genetic kin, we

proceeded to exterminate many of our animal predators. We hunted to extinction

those whose meat we fancied.40

Originally, when Homo

sapiens spread throughout the globe, large animals, known as megafauna, roamed

every continent. There is not enough space in this book to list the animals we

hunted to extinction, but some examples are straight-tusked elephants, woolly

mammoths, woolly rhinoceroses, giant deer, cave bears, and cave lions in

Eurasia; marsupial lions, giant kangaroos, a giant

python, two species of crocodiles, and all large flightless birds in

Australia; mammoths, giant elephants, giant sloths, giant armadillos, stag

moose, mastodons, and the American lion, which was larger than its African

cousin in the New World. Before Homo sapiens arrived, camels and zebras roamed

the plains of North America. Horses thrived for hundreds of thousands of years

before we drove them to extinction on the North American continent around

12,000 BC. (Today's horses were later reintroduced into the Americas by Spanish

settlers in the fifteenth century.)

By 10,000 BC, Homo

sapiens had killed off 80 percent of big animal species in the Americas,

basically those large enough to be worth the meat.42 Some animals we didn’t

hunt to extinction but dramatically reduced their number, and then we put them

in-game parks or zoos. Lions have declined from 450,000 to fewer than twenty

thousand today, and there were once over one million chimpanzees in Africa

compared with an estimated 200,000 currently.44 The total mass of wild animals

is now one-sixth of pre-human levels.43

We accomplished the

extinction of other animal species through a combination of hunting and turning

half of the earth’s dry surface into farms. Of course, domesticated animals are

a different story. Today, just a handful of species - cattle, pigs, sheep,

goats, and Homo sapiens - make up 97 percent of the land animal biomass on

earth.44Homo sapiens continues to exterminate other species, except for those

destined for our table. The current extinction rate for all species is now more

than 100 times higher than before.45 The global population of vertebrates has

declined by 52 percent from 1970 to 2010. One-quarter of all mammals and 10

percent of all plant species today are threatened with extinction.46 All these

species, including the other humans, have vanished into the mists of history.

The 99 percent of all species that once lived and are now dead are not around

to contemplate the prospects for their survival. At one time the future must

have seemed bright for many of these now-extinct species. If given to contemplating

their fate, the dinosaurs were probably looking forward to dominating the

planet for many millions of years to come. Like us, they might have expected to

survive because they had always done so in the past. But if a poll were taken

of all species, the survivors and non-survivors, on the question of whether the

earth is a hospitable place for life, about 99 percent would vote no. The only

ones likely to vote yes - the 1 percent - are those that happened to

survive.

Our future survival may not be as favorable as

they seem

Our journey as a

species to reach the present day has been fraught with many dangers. We have

come close to extinction numerous times, like most species borne on this

planet. If Homo sapiens had evolved before the last 65 million years of the

earth’s 4.5-billion-year history, we would not have survived any of the mass

extinctions. Since then, threats to our survival have come in the form of

periodic ice ages and global warmings, as our planet has tried to freeze or

boil us to death alternately. About seventy thousand years ago we barely

squeezed through a population bottleneck. Some fifty thousand years ago we

battled with the dominant human species on the planet and somehow lived to tell

the tale.

Therefore, we should

be cautious about becoming overly optimistic about our future. If the past is

prologue, then the odds of future survival may not be as favorable as they

seem. The journey ahead may present just as many, or even more, opportunities

to take a wrong turn, leading to joining the other 99 percent of species that

are now extinct.

But that is not the

perspective most of us have about our evolutionary history. We somehow survived

all these threats to our survival in the past and therefore believe we will

somehow continue to do so in the future.47 But this is just an example of survivor

bias. Our perspective on our evolutionary history is distorted because we are

one of the few species that made it. The species that didn’t would have a

different view. We can be easily fooled when we are one of the few winners.

Even though our evolutionary journey to the present day was perilous, many

argue that the road ahead presents significantly fewer dangers. After all, Homo

sapiens currently rule the planet. We have wiped out or put in zoos any species

that threatened us. We have developed powerful technologies to bend the

physical world to our will and enjoy a standard of living hundreds of times

greater than our hunter-gatherer ancestors. To mention two nuclear war and

global warming, the risks of extinction for Homo sapiens are greater than

ever.

About seventy-five

years ago, we placed in the hands of a few the ability to exterminate billions

with atom bombs. Around the same time, we started to spew large amounts of CO2

into the atmosphere, which could someday trigger a runaway greenhouse effect that

fries all life on earth to a crisp. I will argue these new existential threats

put us at greater risk of extinction than at any time since we battled for

survival with the Neanderthals fifty thousand years ago.

Remarkably, the above

two mentioned dangers were predicted sixty-five years ago by a Hungarian

immigrant to the United States. The man who saw this clearly during the 1950s,

both the upsides and downsides of technology, worked at the Institute for Advanced

Studies at Princeton and was a friend of Abraham Wald. This professor cautioned

that new technologies have unforeseen consequences. In 1955, as he lay dying of

cancer near the end of his life, this professor wrote an essay in Fortune that

laid out his concerns. He foresaw much of what would happen in the years to

come, including the proliferation of nuclear weapons and global warming. His

essay was entitled “Can We Survive

Technology?”

1. David Graeber and

David WengrowThe Dawn of Everything: A New History of

Humanity.2021, p. 504.

2. Brusatte, Steve. (2018). The Rise and Fall of the

Dinosaurs. HarperCollins. New York, p. 204.

3. Brannen,

Peter. (2017). The Ends of the World. HarperCollins. New York.. p. 238.

4. Walsh, Bryan.

(2019). End Times. Hachette Books. New York, p. 149.

5. Christian,

David. (2011). Maps of Time. University of California Press. Berkeley,

California, p. 142.

6. Descriptions of

the effects of the comet or asteroid are a combination of Brusatte

(2018), p. 314–315 and Brannen.

7. Walsh,

Bryan (2019), p. 17.

8.The descriptions

of dinosaurs come from Brusatte (2018).

9. Brusatte (2018), p. 336.

10. Brusatte (2018), p. 338.

11. Brusatte (2018), p. 198.

12. Brusatte (2018), p. 200.

13. Brusatte (2018), p. 204.

14. Brusatte (2018), p. 220.

15. Brusatte (2018), p. 219.

16. Everett, Daniel.

(2017). How Language Began: The Story of Humanity’s Greatest Invention.

Liveright Books. New York,p. 126.

17. Finlayson,

Clive. (2010). The Humans Who Went Extinct. Oxford University Press. Oxford,

UK, p. 99.

18. Hawks, John

et al. (2000). “Population Bottlenecks and Pleistocene Human Evolution.”

Molecular Biology and Evolution. January 1, 2000. Vol. 17. No. 1,p. 9.

19. Finlayson

(2010), p. 99.

20. Yost, Chad et al.

(2018). “Subdecadal Phytolith and Charcoal Records

from ~74ka Toba Supereruption.” Journal of Human

Evolution. March 2018. Vol. 116. p. 75–94.

21. Pinker, Steven.

(2019). Enlightenment Now. Penguin Books. New York, p. 294.

22. Sterns, Beverly

et al. (2000). Watching from the Edge of Extinction. Yale University Press. New

Haven, CT, p. x.

23. Pinker (2019),

p. 294.

24. Bertram (2016)

provides a model to quantify this qualitative statement.

25. Scanes, Colin. (2018). Animals and Human Society. Academic

Press, Elsevier. London, p. 84.

26. Papagianni,

Dimitra. (2015). The Neanderthals Rediscovered. Thames & Hudson.

London, p. 21.

27. Lee, Sang-Hee. (2015). Close Encounters with Humankind. W.W. Norton.

New York, p. 176.

28. Lee (2015), p.

184.

29. Papagianni

(2015), p. 13.

30. Reich, David.

(2018). Who We Are and How We Got Here. Pantheon Books. New York, p.

26.

31. Diamond, Jared.

(1999). Guns, Germs, and Steel. W.W. Norton. New York, p. 28, and Reich

(2018), p. 28.

32. Harari, Yuval.

(2015). Sapiens. HarperCollins. New York, p. 145, p. 145.

33. Christian

(2011), p. 175.

34. Keeley, Lawrence.

(1996). War before Civilization. Oxford University Press. Oxford, UK, p. 37.

35. LeBlanc, Steven.

(2003). Constant Battles: Why We Fight. St. Martin’s Press. New York, p. 97.

36. Reich (2018), p.

40.

37. Stringer, Chris.

(2012). Lone Survivors. Times Books. New York.

38. Shipman, Pat.

(2015). The Invaders: How Humans and Their Dogs Drove Neanderthals to

Extinction. Belknap Press. Cambridge, MA.

39. Stringer (2012),

p. 204, Money, Nicholas. (2019). The Selfish Ape. Reaktion

Books. London, p. 70.

40. Brannen (2017),

p. 226–233 for the species humans have driven to extinction.

41. Diamond (1999),

p. 204.

42. Brannen (2017),

p. 240.

43. Money (2019), p.

97.

44. Brannen (2017),

p. 238.

45. Walsh, Bryan.

(2019). End Times. Hachette Books. New York, p. 149.

46. Christian

(2011), p. 142.

47. Like a cat

perched on the windowsill of a high-rise apartment building, we believe our

survival is not at risk. “After all,” the cat may say to itself, “I have rested

outside this open window for many years, peering down at the street fifty

stories below, and nothing bad has happened.” Unfortunately, cats who fell to

their death are not around to reconsider whether a narrow ledge 600 feet above

ground level is the best place to nap.

For updates click homepage here