By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

When humanity almost got

wiped out

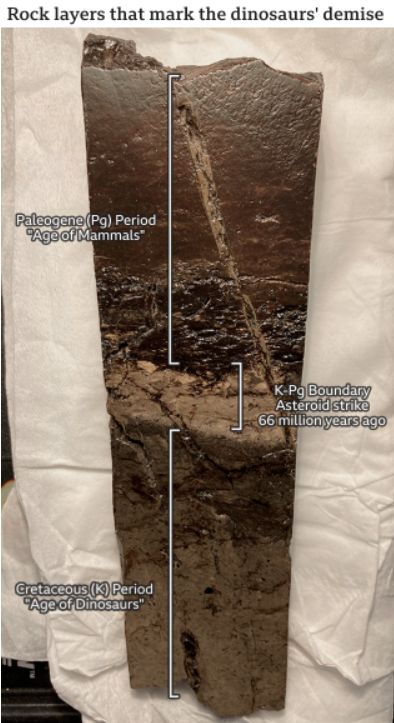

According

to The New York

Times, scientists studying a site in North Dakota

believe they have discovered pieces of an asteroid that slammed into Earth about

66 million years ago off the Yucatán Peninsula. It's believed the object caused

widespread destruction and led to the eventual extinction of the dinosaurs,

which paved the way for mammals to rule the planet.

The asteroid created a 20-mile-deep crater that sent molten debris into

the air that later cooled into "spherules of glass," the newspaper

explained. Experts say these objects are unmistakable signs that an asteroid

impact occurred.

And whether we go with Hobbes or

Rousseau, we are left with the idea that the most we can do to change our

current predicament is a bit of modest political tinkering. Hierarchy and

inequality are the inevitable prices to pay for having genuinely come of age,

yet except what the available evidence shows are that the trajectory of

human history has been a good deal more diverse and exciting and less boring

than we tend to assume because, in an important sense, it has not been a trajectory.

Most people who write history on a grand scale seem to have decided

that, as a species, we are well and truly stuck, and there is really no escape

from the institutional cages we’ve made for ourselves1.

Little discussed is that during the Cretaceous Period, a comet six

miles wide, taller than Mount Everest, and traveling at a hundred times the

speed of a jet plane targeted the earth.2

Some 66 million years ago, a six-mile wide asteroid slammed into the

ocean off Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, carving out a 110-mile wide crater known

as Chicxulub. The impact kicked off wildfires and tsunamis across

thousands of miles. Then swings in global climate, ushering in the extinction

of 75 percent of all species.

The dominant land animals on earth before the comet's arrival were

dinosaurs.3 Right up until that day, the future of the dinosaurs looked pretty

bright. They were at the top of the food chain, without equal, and there were

no signs of that changing.

We accomplished the extinction of other animal species through a

combination of hunting and turning half of the earth’s dry surface into farms.3

Of course, domesticated animals are a different story. Today, just a handful of

species - cattle, pigs, sheep, goats, and Homo sapiens - make up 97 percent of

the land animal biomass. Homo sapiens continues to exterminate other species,

except for those destined for our table. The current extinction rate for all

species is now more than 100 times higher than before. The global population of

vertebrates has declined by 52 percent from 1970 to 2010.4One-quarter of all

mammals and 10 percent of all plant species today are threatened with

extinction.4 All these species, including the other humans, have vanished into

the mists of history. The 99 percent of all species that once lived and are now

dead are not around to contemplate the prospects for their survival. At one

time, the future must have seemed bright for many of these now-extinct species.

If given to contemplating their fate, the dinosaurs were probably looking

forward to dominating the planet for many millions of years. Like us, they

might have expected to survive because they had always done so in the past. But

if a poll were taken of all species, the survivors and non-survivors, on

whether the earth is a hospitable place for life, about 99 percent would vote

no. The only ones likely to vote yes - the 1 percent - are those that happened

to survive.

We are fortunate that a small comet passed by us in 1736. We are equally

lucky that a large one struck the earth 6 million years ago.

During the Cretaceous

Period, a comet six miles wide, taller than Mount Everest, and traveling at a

hundred times the jet plane's speed targeted the earth.5 The comet (or

asteroid; exactly which is still debated) entered the atmosphere, created a

vacuum that sucked up hundreds of millions of tons of dirt into the clouds, and

then smashed into the Yucatan Peninsula with the energy equivalent of a billion

atoms bombs, leaving a hole in the ground twenty-five miles deep and more than

one hundred miles wide. The resulting fires circled most of the planet, burning

forests and plant life, instantly roasting any animal in its path into charred

ash. Within minutes, the “ejecta” - liquefied rocks sent into the atmosphere

from what is now Mexico - rained down upon the planet, and a hail of lethal

projectiles shredded animals not previously incinerated into little pieces of

bone and flesh. The shock to the earth’s crust set off magnitude 12 earthquakes

around the globe that shallowed up parts of whole continents, ignited massive

volcanic eruptions that covered millions of square miles of land in molten

lava, and triggered tsunamis that flushed sea life hundreds of miles inland.

Ninety percent of the biomass of the earth was suddenly gone.6

And then it got cold

The ejecta and dirt in the clouds smoke from planetary-scale forest

fires, and ash from volcanic eruptions blocked the sun’s rays. Global

temperatures may have plummeted as much as fifty degrees over land and

thirty-six degrees over the oceans. Less than 1 percent of sunlight reached the

planet's surface, halting photosynthesis. Many creatures still alive soon

starved to death on frozen landscapes.7 The earth had gone from fireball to

snowball.

Bad News for Dinosaurs:

Good News for Us

The dominant land animals on earth before the comet's arrival were

dinosaurs.8 They were at the top of the food chain, without equal and with no

signs of change.

We would not have made it if Homo sapiens had been alive when the comet

struck.9 But some animals did survive. A few tiny dinosaurs with wings were not

killed. Maybe they were nesting in caves on that fateful day, or flight allowed

them to scour the earth for food, such as seeds or the roasted animal carcasses

that littered the earth. These small, winged dinosaurs managed to find food and

evolved to become today’s birds. Many species of fish, protected by the vast,

deep oceans, also survived. And a few small mammals, about the size of rodents,

somehow lived through this global holocaust. The descendants of these rat-like

creatures would evolve to write books about dinosaurs and survivor bias.10

The king of the dinosaurs was Tyrannosaurus rex, or T. rex for short.

Some forty feet long, weighing seven or eight tons, T. rex was one of the

largest meat-eating animals ever to walk the face of the earth.11 Its skull was

five feet in length with eyes the size of grapefruits and a jawbone lined with

fifty or so knife-sharp teeth.12 Unlike us, T. rex could regrow broken teeth,

which was helpful given its table manners.13 The king of the dinosaurs

benefited from exceptional senses: binocular vision thirteen times better than

modern humans, and the ability to hear and smell other animals at great

distances.14 Above all, T. rex was thought to have been among the smartest

animals around at that time.15

When a large comet struck the earth, this was bad news for dinosaurs

but good news for us. Most believe that Homo sapiens could not have coexisted

with such carnivorous beasts. We probably would have been a tasty appetizer: a

tall, moderately sized, fleshy mammal who ran upright (easily spotted) and

could not run that fast (easily caught). We can be thankful our ancestors were

small, ground-hugging, sub-snack-sized rodents, not worth pursuing. Probably

our ancestors’ main concern was not to get accidentally stepped on. We have not

discovered any preserved T. rex or other dinosaur brains, so the best evidence

of intelligence is the encephalization quotient (EQ), the ratio of brain mass

to body size. As an indication of intelligence, EQ has drawbacks because the

size of the individual components of the brain is important. For example, the

size of the neocortex matters more than that of the limbic system as an

indicator of intelligence. Nevertheless, EQ is roughly correlated with IQ. T.

rex had an EQ of 2.0 to 2.4. That is about twice that of a dog, more than a

chimpanzee, and about one-third of a modern adult human.16

If T. rex had survived, we can only speculate how far another 65

million years of brain evolution would have taken their species. When humans

first evolved, our intelligence was about the same as that of T. rex. During

six million years of human evolution, our brain size has almost tripled: Our EQ

started at 2.5 and eventually rose to 5.8.1719, But T. rex would have had a

65-million-year head start on brain evolution. Even if Homo sapiens somehow

could have found a way to coexist with T. rex, it is unclear which would have

become the more intelligent and dominant species.

A Planet Better at

Preserving Fossils than Life

Sixty-five million years ago was not the first time most living

organisms on earth were exterminated. In fact, the space rock that killed the

large dinosaurs was the most recent of five mass extinctions, defined as events

in which most species on earth perished.

The “big five” mass extinctions and the percentage of species lost

were:

• Ordovician: 444 million years ago (mya), 86

percent

• Devonian: 375 mya, 75 percent

• Permian: 251 mya, 96 percent

• Triassic: 200 mya, 80 percent

• Cretaceous: 65 mya, 75 percent

We could not have survived if we had been around during any of those

five mass extinction events. We are fortunate not to have been alive during the

first 95 percent of the earth’s 4.5-billion-year history.

In particular, the Permian mass extinction, known as the Great Dying,

was a close call for all life on earth. A dramatic global rise in temperatures

due to volcanic eruptions dumping massive amounts of CO2 into the skies killed

almost every land species. Oceans turned acidic, burning through the gills and

shells of most sea life. If all life had ended, we don’t know how long it would

have taken for it to restart, if ever. Even if it had, we don’t know how much

time would have passed before life once again reached the Permian stage of evolution.

The evolutionary climb to the heights of Permian life took over four billion

years after the earth formed. Hence, life might not have restarted, or

evolution could have followed a different path. It is doubtful that any other

path would have taken the same millions of twists and turns that yielded. Homo

sapiens. We are lucky descendants of the fortunate small percentage of all

species that have survived these mass extinctions.

Homo sapiens has existed as a distinct species for more than 200,000 years.

Despite that, as demonstrated by DNA evidence, modern-day humans evolved from a

group of common ancestors who lived just seventy thousand years ago.17 After

numbering perhaps hundreds of thousands of individuals at one time, the number

of Homo sapiens fell to as low as several thousand individuals.18 Such a

substantial fall in numbers risked the extinction of our species: A population

of merely thousands provides insufficient genetic variation for natural

selection to adapt to environmental change and can lead to life-threatening

genetic deformities from inbreeding.

The causes of this “bottleneck” in the Homo sapiens population are

still debated. The most likely explanation is that during this time, a volcano,

whose caldera today is Lake Toba in Sumatra, Indonesia, erupted in the largest

explosion on earth in the past two million years.19 The Toba eruption spit ash

into the skies that blocked out the sun’s rays, cooling the planet for more

than a thousand years. However, some have argued that the impact on equatorial

Africa's climate, where most Homo sapiens lived, was not significant.20 Other

reasons for the population bottleneck could be that Homo sapiens were

outnumbered by other humans, such as the Neanderthals, and may have suffered

devastating attacks from these competing human species. Diseases could have

also played a role, but determining the presence of pathogens from ancient

skeletal remains is challenging. Or maybe it was some combination of all the

above. Regardless, Homo sapiens barely survived, passing through a tight

population bottleneck that could have easily led to our extinction.

As survivors, we tend to believe that the survival of our species was

likely, even inevitable. We are inclined to believe that the journey must not

have been perilous. That fails to account for survivor bias. The path that we

took might have been one of the few that did not.

What we do know is that most species don’t make it. Ninety-nine percent

of all species that once lived on the earth are gone.21 The vast majority of

species on our planet have lasted from one to ten million years.22 Mammals like

us are particularly vulnerable, surviving only about a million years on

average.23 Compared with many other species, humans have a larger mass, which

requires more energy when we hunt for food - and offers more food when hunted.

Our warm blood demands reliable nutrients to maintain a constant internal body

temperature. Our reproductive cycle has a high infant mortality rate (and

maternal mortality rate), and we birth helpless infants completely dependent on

adults for survival. These vulnerabilities are exacerbated by extended

adolescence and, therefore, a greater risk of death from predators. In

addition, lower birth rates constrain our ability to adapt to a changing world

through natural selection. Homo sapiens can procreate about once a year, but

cockroaches give birth monthly. Some bacteria divide into new cells every

twenty minutes.

The primary reason species don’t last because the earth’s physical

environment constantly changes. For all but a few species, the speed of that

change eventually outruns the pace of adaptation. Charles Darwin called this

series of adaptations “evolution,” which he defined as “descent with

modification.” But the earth’s physical environment changes faster than just

about any organism can adapt.24 Sometimes, the change in the environment is

gradual, such as an ice age, and other times sudden and violent, like a comet

strike, a massive earthquake, or a volcanic eruption.

In any case, the earth is better at preserving fossils than life.

Despite all this, Homo sapiens has survived and flourished. We dominate the

earth's landmasses, from soaring mountains freezing in the clouds to tropical

islands baking in the sun. We are the most intelligent species that has ever

lived, as complex, symbolic language gives us the amazing ability to share

knowledge with billions of fellow humans and pass on what we have learned to

subsequent generations. We may extend that domination to the planets whirling around

our sun in the next hundred years.

But our journey to today’s world was actually quite perilous. Some

fifty thousand years ago, at least five human species - Homo Denisova,

Homo Floresiensis, Homo Naledi, Homo Neanderthalensis, and Homo Sapiens - coexisted

on earth.25 Our species is the only survivor, the last humans.

Two Enter, One Leave

Homo sapiens first appeared in northern Africa around 200,000 BC, the

descendants of an early human species, Homo erectus. Sometime around 120,000

BC, Homo sapiens started trickling up into Europe, and then a large wave

migrated north about 50,000 BC. There, we encountered Homo

neanderthalensis, more commonly

known as the Neanderthals.

Neanderthals were the most dominant human species, outnumbering all

others combined.26 Neanderthals had left Africa much earlier, about 800,000 BC,

and moved up into Europe. By 400,000 BC, Neanderthals were spread throughout

Europe and Asia.

Named after the first specimen found in 1856 by miners in the Neander

Valley of Germany, Neanderthals shared many anatomical and cultural

characteristics of Homo sapiens. Neanderthals were comparable in height,

although much heavier in the body, with stronger and thicker arms and legs, a

protruding jaw, and a thick-walled skull that rode on top of broad shoulders.

Homo sapiens and Neanderthals were equally advanced. Neanderthal brains were as

large as those of Homo sapiens,27 and like Homo sapiens, Neanderthals had

language skills.3035 Both species shaped stone tools, crafted jewelry, painted

cave walls, buried their dead, and lived on comparable diets.3136 Although

physically imposing, Neanderthals in other respects were not that different

from modern Homo sapiens. It has been said that a Neanderthal on a New York

City subway would go unnoticed “provided that he was bathed, shaved, and

dressed in modern clothing.”28

Within thousands of years of Homo sapiens arriving in Europe,

Neanderthals died out, followed by the extinction of the other human species

around the globe.29 The cause of such a rapid extinction of all humans on earth

except for Homo sapiens is unknown. However, archaeologists have put forward

several explanations. The most commonly accepted theory is that we slaughtered

them, or what has become quaintly known as the Replacement Theory.30

As Homo sapiens moved into the Neanderthal territory, the frequency of

violent interactions likely increased. There are indications that Homo sapiens

had better language abilities than other human species. However, our language

skills at that time would still have been primitive and limited.31 Consistent

with an ability to better coordinate and communicate, Homo sapiens might have

been more cunning warriors. It appears many Neanderthal men met an unnatural

demise. Neanderthal male skeletal remains support this theory that evidence

skulls pierced by arrowheads or foreheads caved in by rocks. One survey of male

Neanderthal skeletons showed that 40 percent suffered traumatic head

injuries.32 There is also evidence of widespread cannibalism. Neanderthal

skulls were often broken in places that would facilitate the extraction of

juicy brain matter, and long bones were shattered in ways to ease the scooping

of moist bone marrow.35

Homo sapiens also bred with Neanderthals. DNA evidence confirms that

Homo sapiens carry genomes from Neanderthals that range from 1.5 percent in

Europeans to 2.1 percent in Asians.36 Homo sapiens men may have killed

Neanderthal men to access Neanderthal women.37 Given the small bands of

hunter-gatherers in which humans traveled at that time, interbreeding within a

group of forty or fifty individuals could produce genetic anomalies. Homo

sapiens men who reproduced with Neanderthal women gave their offspring an

evolutionary advantage.

An alternative explanation is that Homo sapiens were better hunters,

and eventually the Neanderthals starved to death. It is not clear why that

would be the case: Neanderthals were physically stronger and had established

themselves in Europe and Asia long before us. Another theory is we drove

Neanderthals to extinction because we domesticated wolves (today’s dogs) for

hunting and the Neanderthals didn’t.3840 It is difficult to know how important

dogs were to food gathering or keeping watch for predators. Still, it seems

unlikely that pets – even working pets – are mainly responsible for the

extinction of the Neanderthals. Yet another theory is that Homo sapiens

infected Neanderthals with lethal diseases we carried within us from Africa.

Because the Neanderthals left Africa hundreds of thousands of years before us, they

may have lost immunity to African pathogens.3941 This would be consistent with

other mass human genocides, such as when Europeans arrived in the New World.

However, particular diseases are difficult to detect in fossils, so there is no

direct evidence of the “disease out of Africa” theory.

Based on what is known recently, the extinction of the Neanderthals was

most likely due to Homo sapiens slaughtering Neanderthal men and capturing

Neanderthal women. With the Neanderthals out of the way, we could have readily

vanquished the remaining less-numerous human species employing a similar

strategy. However, the Neanderthals could have just as easily won this

interspecies battle for survival. In fact, given their vastly greater numbers

and far superior physical strength, Neanderthals probably were the odds-on

favorite. And then Neanderthals would have been the ones writing books about

those primitive, now-extinct Homo sapiens.

Furthermore, we did not just kill off other humans. After vanquishing

our nearest genetic kin, we exterminated many of our animal predators. We

hunted to extinction those whose meat we fancied.40

Originally, when Homo sapiens spread throughout the globe, large

animals, known as megafauna, roamed every continent. There is not enough space

in this book to list the animals we hunted to extinction, but some examples are

straight-tusked elephants, woolly mammoths, woolly rhinoceroses, giant deer,

cave bears, and cave lions in Eurasia; marsupial lions, giant kangaroos, a giant python, two species of

crocodiles, and all large flightless birds in Australia; mammoths, giant

elephants, giant sloths, giant armadillos, stag moose, mastodons, and the

American lion, which was larger than its African cousin in the New World.

Before Homo sapiens arrived, camels and zebras roamed the plains of North

America. For hundreds of thousands of years, horses thrived before we drove

them to extinction on the North American continent around 12,000 BC. (Today’s

horses were later reintroduced into the Americas by Spanish settlers in the

fifteenth century.)

By 10,000 BC, Homo sapiens had killed off 80 percent of big animal

species in the Americas, basically those large enough to be worth the meat.42

Some animals we didn’t hunt to extinction but dramatically reduced their

number, and then we put them in-game parks or zoos. Lions have declined from

450,000 to fewer than twenty thousand today, and there were once over one

million chimpanzees in Africa compared with an estimated 200,000 currently.44

The total mass of wild animals is now one-sixth of pre-human levels.43

We accomplished the extinction of other animal species through a

combination of hunting and turning half of the earth’s dry surface into farms.

Of course, domesticated animals are a different story. Today, just a handful of

species – cattle, pigs, sheep, goats, and Homo sapiens – make up 97 percent of

the land animal biomass.44 Homo sapiens continues to exterminate other species,

except for those destined for our table. The current extinction rate for all

species is now more than 100 times higher than before.45 The global population

of vertebrates has declined by 52 percent from 1970 to 2010. One-quarter of all

mammals and 10 percent of all plant species today are threatened with

extinction.46 All these species, including the other humans, have vanished into

the mists of history. The 99 percent of all species that once lived and are now

dead are not around to contemplate the prospects for their survival. At one

time the future must have seemed bright for many of these now-extinct species.

If given to contemplating their fate, the dinosaurs were probably looking

forward to dominating the planet for many millions of years. Like us, they

might have expected to survive because they had always done so in the past. But

if a poll were taken of all species, the survivors and non-survivors, on

whether the earth is a hospitable place for life, about 99 percent would vote

no. The only ones likely to vote yes – the 1 percent – are those that happened

to survive.

Our future survival

may not be as favorable as they seem

Our journey as a species to reach the present day has been fraught with

many dangers. We have come close to extinction numerous times, like most

species borne on this planet. If Homo sapiens had evolved before the last 65

million years of the earth’s 4.5-billion-year history, we would not have

survived any of the mass extinctions. Since then, threats to our survival have

come in the form of periodic ice ages and global warmings, as our planet has

tried to freeze or boil us to death alternately. About seventy thousand years

ago we barely squeezed through a population bottleneck. Some fifty thousand

years ago we battled with the dominant human species on the planet and somehow

lived to tell the tale.

Therefore, we should be cautious about becoming overly optimistic about

our future. If the past is prologue, then the odds of future survival may not

be as favorable as they seem. The journey ahead may present just as many, or

even more, opportunities to take a wrong turn, leading to joining the other 99

percent of species that are now extinct.

But that is not the perspective most of us have about our evolutionary

history. We somehow survived all these threats to our survival in the past and

therefore believe we will somehow continue to do so in the future.47 But this

is just an example of survivor bias. Our perspective on our evolutionary

history is distorted because we are one of the few species that made it. The

species that didn’t would have a different view. We can be easily fooled when

we are one of the few winners. Even though our evolutionary journey to the

present day was perilous, many argue that the road ahead presents significantly

fewer dangers. After all, Homo sapiens currently rule the planet. We have wiped

out or put in zoos any species that threatened us. We have developed powerful

technologies to bend the physical world to our will and enjoy a standard of

living hundreds of times greater than our hunter-gatherer ancestors. To mention

two nuclear war and global warming, the extinction risks for Homo

sapiens are greater than ever.

About seventy-five years ago, we placed in the hands of a few the

ability to exterminate billions with atom bombs. Around the same time, we spew

large amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere, which could someday trigger a runaway

greenhouse effect that fries all life on earth to a crisp. I will argue that

these new existential threats put us at greater risk of extinction than ever

since we battled for survival with the Neanderthals fifty thousand years

ago.

The above-mentioned dangers

were predicted sixty-five years ago by a Hungarian immigrant to the United

States. The man who saw this clearly during the 1950s, both the upsides and

downsides of technology, worked at the Institute for Advanced Studies at

Princeton and was a friend of Abraham Wald. This professor cautioned that new

technologies have unforeseen consequences. In 1955, as he lay dying of cancer

near the end of his life, this professor wrote an essay in Fortune that laid

out his concerns. He foresaw much of what would happen in the years to come,

including the proliferation of nuclear weapons and global warming. His essay

was entitled “Can

We Survive Technology?”

1. David Graeber and

David WengrowThe Dawn of Everything: A New

History of Humanity.2021, p. 504.

2. Brusatte, Steve. (2018). The Rise and Fall of the

Dinosaurs. Harper Collins. New York, p. 204.

3. Brannen,

Peter. (2017). The Ends of the World. HarperCollins. New York.. p. 238.

4. Walsh, Bryan.

(2019). End Times. Hachette Books. New York, p. 149.

5. Christian, David.

(2011). Maps of Time. University of California Press. Berkeley,

California, p. 142.

6. Descriptions of

the effects of the comet or asteroid are a combination of Brusatte (2018), p. 314–315 and Brannen.

7. Walsh,

Bryan (2019), p. 17.

8.The descriptions

of dinosaurs come from Brusatte (2018).

9. Brusatte (2018), p. 336.

10. Brusatte (2018), p. 338.

11. Brusatte (2018), p. 198.

12. Brusatte (2018), p. 200.

13. Brusatte (2018), p. 204.

14. Brusatte (2018), p. 220.

15. Brusatte (2018), p. 219.

16. Everett, Daniel.

(2017). How Language Began: The Story of Humanity’s Greatest Invention.

Liveright Books. New York,p. 126.

17. Finlayson,

Clive. (2010). The Humans Who Went Extinct. Oxford University Press. Oxford,

UK, p. 99.

18. Hawks, John

et al. (2000). “Population Bottlenecks and Pleistocene Human Evolution.”

Molecular Biology and Evolution. January 1, 2000. Vol. 17. No. 1,p. 9.

19. Finlayson

(2010), p. 99.

20. Yost, Chad et al.

(2018). “Subdecadal Phytolith and Charcoal

Records from ~74ka Toba Supereruption.” Journal

of Human Evolution. March 2018. Vol. 116. p. 75–94.

21. Pinker, Steven.

(2019). Enlightenment Now. Penguin Books. New York, p. 294.

22. Sterns, Beverly

et al. (2000). Watching from the Edge of Extinction. Yale University Press. New

Haven, CT, p. x.

23. Pinker (2019),

p. 294.

24. Bertram (2016)

provides a model to quantify this qualitative statement.

25. Scanes, Colin. (2018). Animals and Human Society. Academic

Press, Elsevier. London, p. 84.

26. Papagianni, Dimitra. (2015). The Neanderthals Rediscovered.

Thames & Hudson. London, p. 21.

27. Lee, Sang-Hee. (2015). Close Encounters with Humankind. W.W. Norton.

New York, p. 176.

28. Lee (2015), p.

184.

29. Papagianni (2015), p. 13.

30. Reich, David.

(2018). Who We Are and How We Got Here. Pantheon Books. New York, p.

26.

31. Diamond, Jared.

(1999). Guns, Germs, and Steel. W.W. Norton. New York, p. 28, and Reich

(2018), p. 28.

32. Harari, Yuval. (2015).

Sapiens. HarperCollins. New York, p. 145, p. 145.

33. Christian

(2011), p. 175.

34. Keeley, Lawrence.

(1996). War before Civilization. Oxford University Press. Oxford, UK, p. 37.

35. LeBlanc, Steven.

(2003). Constant Battles: Why We Fight. St. Martin’s Press. New York, p. 97.

36. Reich (2018), p.

40.

37. Stringer, Chris.

(2012). Lone Survivors. Times Books. New York.

38. Shipman, Pat.

(2015). The Invaders: How Humans and Their Dogs Drove Neanderthals to

Extinction. Belknap Press. Cambridge, MA.

39. Stringer (2012),

p. 204, Money, Nicholas. (2019). The Selfish Ape. Reaktion Books.

London, p. 70.

40. Brannen (2017),

p. 226–233 for the species humans have driven to extinction.

41. Diamond (1999),

p. 204.

42. Brannen (2017),

p. 240.

43. Money (2019), p.

97.

44. Brannen (2017),

p. 238.

45. Walsh, Bryan.

(2019). End Times. Hachette Books. New York, p. 149.

46. Christian

(2011), p. 142.

47. Like a cat

perched on the windowsill of a high-rise apartment building, we believe our

survival is not at risk. “After all,” the cat may say to itself, “I have rested

outside this open window for many years, peering down at the street fifty

stories below, and nothing bad has happened.” Unfortunately, cats who fell to

their death are not around to reconsider whether a narrow ledge 600 feet above

ground level is the best place to nap.

For updates click hompage here