By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Ötzi The Iceman

It was at first

believed that the Iceman was free of diseases, but in 2007 researchers

discovered that his body had been infested with whipworm and that he had

suffered from arthritis; neither of these conditions contributed to his death.

He also, at one time, had broken his nose and several ribs. His few remaining

scalp hairs provide the earliest archaeological evidence of haircutting, and

short blue lines on his skin (lower spine, left leg, and right ankle) have been

variously interpreted as the earliest known tattoos or as scars remaining from

a Neolithic therapeutic procedure.

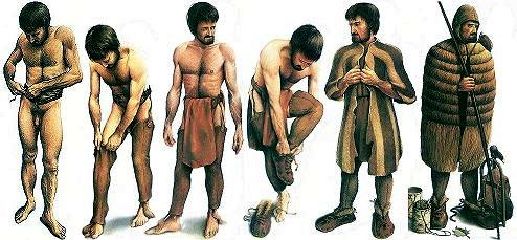

The various clothes

and accouterments found with him are truly remarkable since they formed the

gear of a Neolithic traveler. The Iceman’s basic piece of clothing was an

unlined fur robe stitched together from pieces of ibex, chamois, and deer skin.

A woven grass cape and a furry cap provided additional protection from the

cold, and he wore shoes made of leather and stuffed with grass. The Iceman was

equipped with a small copper-bladed ax and a flint dagger, both with wooden

handles; 14 arrows made of viburnum and dogwood, two of which had flint points

and feathers; a fur arrow quiver and a bow made of yew; a grass net that may

have served as a sack; a leather pouch; and a U-shaped wooden frame that served

as a backpack to carry this gear. His scant food supply consisted of sloe

berries, mushrooms, and a few gnawed ibex bones.

Ötzi

the Iceman, named after the valley in which he was found, became world-famous

because his body had been remarkably well preserved by the intense cold,

making him the oldest European mummified human. Scientists began examining Ötzi, and soon a startling series of discoveries emerged.

Dark eyes, receding

black hair, few or no freckles, and a darker skin tone. This is how Ötzi the iceman, the mummified corpse found trapped in the

ice of the Italian Alps, would have looked while living.

Researchers who

conducted a higher-coverage genome analysis to learn more about Ötzi’s genetic history and the mummified man’s physical

appearance have found genes associated with male-pattern baldness and darker

skin tone. It is the darkest skin tone recorded in contemporary European individuals

meaning the Caucasian look appears to be a more recent development with earlier

a sort of 'out of Africa' skin color.

Ötzi’s genomes were first sequenced in 2012. That analysis

resulted in traits of a light-skinned, light-eyed hairy male in contrast to the

current findings, which the development of DNA sequencing technology has

helped. Sequencing technology has advanced, allowing researchers to generate a

high-coverage genome with more accurate analysis. This allowed them to gain new

information and correct earlier findings.

The study indicates

that Ötzi had a dark-skinned complexion during his

lifetime, an idea supported by a previous analysis of Ötzi’s

skin that found brown melanin granules in the deepest layer of the epidermis.

The recent findings also dispute the previously thought ancestry of the iceman.

Research revealed that the iceman had many genes in common with the early

farmers from Anatolia.

There were also no

traces of eastern European Steppe herders. The proportion of hunter-gatherer

genes in Ötzi’s genome is very low.

Ötzi

and Meridians?

A team of European

researchers has analyzed the tattoos scattered across Ötzi’s

body and the various herbs and medicines found alongside his remains to paint a

clearer picture of the Iceman’s community and its ancient medical practices,

reports Joshua Rapp Learn for Science magazine. The scientists’ findings, newly published in

the International

Journal of Paleopathology,

suggest Ötzi belonged to a society with a

surprisingly advanced healthcare system.

Previous studies of

the Iceman’s tattoos have hypothesized that the lines and crosses etched into

his skin offered therapeutic benefits rather than simply serving as decorative

embellishments. Ancient Origins’ April Holloway writes that the tattoos,

created via small incisions traced with charcoal, align with “hard-working

areas of the human body,” including the ankles, wrists, knees, and lower back.

These spots are commonly associated with acupuncture treatments, raising the

possibility that Ötzi’s community knew of the

practice some 2,000 years before it was believed to have first emerged in Asia.

Archaeologists

initially mapped Ötzi’s 61 inkings

in 2015, Carl Engelking reports for Discover magazine. Before this examination, researchers thought the

Iceman’s tattoos numbered closer to 59. Multispectral imaging analysis revealed

a set of previously unidentified tattoos clustered on the Iceman’s chest,

an area commonly associated with acupuncture points

targeting intestinal disorders.

The new study draws

on this existing body

of knowledge to

argue that Ötzi’s tattoos required “considerable

effort … and, irrespective of the efficacy of the treatment, provided care for

the Iceman.” The authors further stipulate that if Ötzi’s

peers developed acupuncture, they must have undergone an extended trial and

error spurred by the desire and ability to develop medical practices.

Plants in the

Iceman’s belongings support the study’s portrait of an inquisitive, complex

society. Birch polypore fungus tied to the leather bands of Ötzi’s

tools may have calmed inflammation or act as an antibiotic, Science’s

Rapp Learn notes, while bracken fern detected in his stomach could have served

as a tapeworm treatment. Traces of bog moss mirror makeshift bandages.

Given the

sophisticated set of tools Ötzi wielded and the

“intentional design elements” apparent in his clothing, it’s not a stretch to

emphasize craftsmanship to the Copper Age community’s medical practices.

Previous studies have

found that Ötzi carried several suspected medicines

either on him or in him. Fastened to leather bands in his equipment,

researchers found the birch polypore fungus, which the Iceman may have used to

calm inflammation or as an antibiotic. Scientists also found a bracken fern in

his stomach, which can be used to treat intestinal parasites such as tapeworms.

And Ötzi was covered with 61 tattoos (such as the one

on his back, pictured above), including dotlike points around joints.

There is evidence of

quite detailed attention to the preparation of clothing with which to dress

against the cold:

And evidence of a

sophisticated range of tools:

In the new study,

scientists looked closer at Ötzi's tattoos. Some

lines and dots were directly over his wrist and ankles, which suffered from

degenerative diseases, and many

correspond to traditional acupuncture points, they report in the International Journal of

Paleopathology. The markings would have taken a long time to produce, and

this sophisticated practice—along with the variety of herbs and medicines—would

have likely been developed through a dedicated, systematic trial-and-error

approach that was passed down through generations in the society in which Ötzi lived, the team concludes.

All of this—combined

with the sophisticated use of plants and fungi to treat ailments—suggests Ötzi was part of a culture with some knowledge of anatomy,

how diseases arise, and how to treat them, the scientists say. What they don't

know is whether any of these treatments worked.

For updates click hompage here