By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

India Today

Today India is going

through an

election cycle. As we posted an article referring to Modi and Ayurveda when they claimed they had a cure

for Covid-19 on 15 August, we commented on

India’s prime minister’s annual Independence Day speech. It is good to revisit

this subject and explain what Narendra Modi stands for.

India claims to be

the largest democracy in the world, and its ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), claims to be the largest

political organization in the world (with a membership base even more significant than that of the Chinese

Communist Party). Since May 2014, the BJP and the government have been in

thrall to the wishes—and occasionally the whims—of a single individual, Indian

Prime Minister Narendra Modi. An extraordinary personality cult has been

constructed around Modi. Its manifestations are visible in the state and party

propaganda, in eulogies in the press, and adulatory invocations of his

transformative leadership by India’s leading entrepreneurs, celebrities, and

sports stars.

A hundred years after

the rise of Hitler and Mussolini, the world is again witnessing the rise of authoritarian

leaders in countries with a democratic history. A partial listing of these

elected autocrats would include Russia’s Vladimir Putin, China's Xi Jinping today, Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan,

Hungary’s Viktor Orban, Narendra Modi, and, not

least, the autocrat temporarily out of favor but longing for a

return to power, former U.S. President Donald Trump.

These leaders have

all personalized governance and admiration to a considerable degree. They all

seek to present themselves as the savior or redeemer of their nation, uniquely

placed to make it more prosperous, more powerful, and more in tune with what

they claim to be its cultural and historical heritage. In a word, they have all

constructed, and been allowed to construct, personality cults around

themselves.

India is soon the

most populous nation in the world, surpassing China. Hence, this cult will have

deeper and possibly more portentous consequences than such cults erected

elsewhere.

And perhaps most

important, this personality cult has taken shape in a country that until

recently had fairly robust and long-standing

democratic traditions. Before Narendra Modi came to power in May

2014, India had a longer-lasting democracy than when Erdogan came to power in

Turkey, Orban in Hungary, and Bolsonaro in Brazil.

The 2014 general election was India’s 16th national vote, in a line extending

almost unbroken from 1952. Regular, and likewise mostly free and fair,

elections have also been held to form the legislatures of different Indian

states. As the historian Sunil Khilnani has pointed out, many more people have voted in Indian elections than

in older and professedly more advanced democracies such as the United Kingdom

and the United States. India, before 2014 also had an active culture of public

debate, a moderately free press, and a reasonably independent judiciary. It was

by no means a perfect democracy—but then no democracy is.

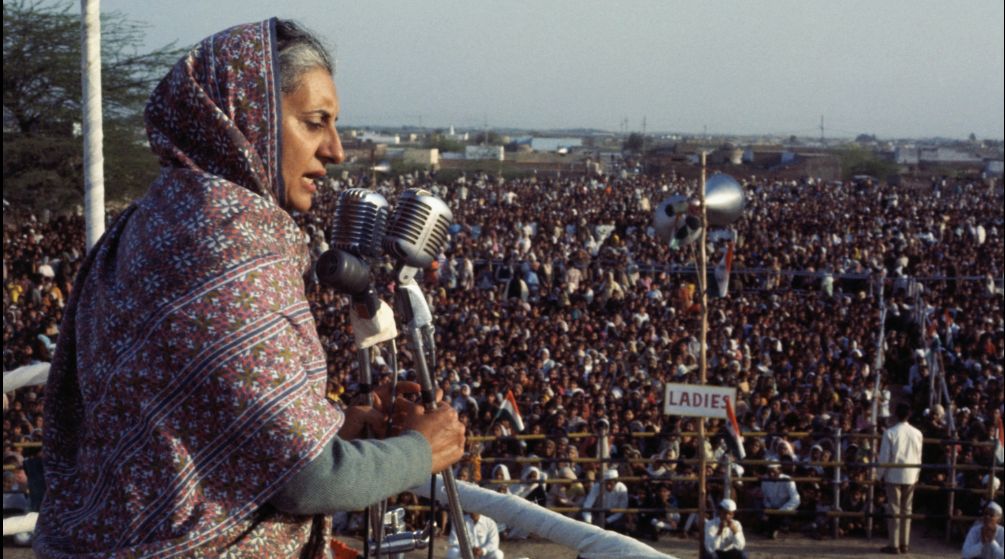

Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi addresses a crowd

in New Delhi on March 3, 1977

At this point one

should also mention something about the cult of a previous Indian prime minister, Indira Gandhi. She was the

daughter of the country’s first and longest-serving prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru who had to oversea

India's painfull partition. In March 1971, Gandhi

and the Indian National Congress party won an emphatic victory in the general

election; that December, India won an emphatic victory on the battlefield over

Pakistan, in part because of Gandhi’s decisive leadership. She was hailed as a

modern incarnation of Durga, the militant, all-conquering goddess of Hindu

mythology. The idea that Gandhi embodied in her person the party, the

government, and the state—and that she represented in herself the past,

present, and future of the nation—was promoted by the prime minister’s

political allies. Congress party leader D.K. Barooah

proclaimed, “India is Indira, Indira is India.” Equally noteworthy is a Hindi

couplet that Barooah composed in praise of Gandhi,

which in English reads: “Indira, we salute your morning and your evening,

too / We celebrate your name and your great work, too.”

Shortly after the

Congress leader read those lines at a rally in June 1975 attended by a million

people, Gandhi imposed a state of emergency, during which her regime arrested

all major (and many minor) opposition politicians as well as trade unionists

and student activists, imposed strict censorship on the press, and abrogated

individual freedoms. A little under two years later, however, Gandhi’s

democratic conscience compelled her to call fresh elections in which she and

her party lost power.

Modi is India, India is Modi

“Modi is India, India

is Modi” is the spoken or unspoken belief of everyone in the BJP, whether

minister, member of Parliament or humble party worker. In September India’s

external affairs minister, S. Jaishankar, told an audience in Washington that “the fact that

our [India’s] opinions count, that our views matter, and we have today the

ability to shape the big issues of our time” is because of Modi. The

anti-colonial movement led by Mohandas Gandhi, the persistence (against the

odds) of electoral democracy since independence, the dynamism of its

entrepreneurs in recent decades, the contributions of its scholars, scientists,

writers, and filmmakers—all this (and the legacy of past prime ministers, too)

goes entirely erased in these assessments. India’s achievements (such as they

are) are instead attributed to one man alone, Modi.

Meanwhile, a

then-serving Supreme Court judge called Modi an “internationally acclaimed visionary”

and a “versatile genius who thinks globally and acts locally.” And India’s

wealthiest and most successful industrialists compete with one another in

publicly displaying their adoration of, and loyalty toward, the prime minister.

In February 2021,

Modi joined the ranks of Stalin, Hitler, Mao, Muammar al-Qaddafi, and Saddam

Hussain in having a sports stadium named after him while he was alive (and in

office). The cricket stadium in the city of Ahmedabad, previously named after

the great nationalist stalwart Vallabhbhai Patel, was henceforth to be called

the Narendra Modi Stadium, with the inauguration of the refurbished premises

conducted by then-Indian President Ram Nath Kovind, no less, alongside Home

Minister Amit Shah and other officials.

Later that year, as

Indian citizens received their first COVID-19 vaccines, they were given vaccination certificates with Modi’s

photograph. The

official certificates also had the prime minister’s photograph as second and then

booster doses were offered. Indians asked to show their COVID-19 certificates

when traveling overseas have since become accustomed to being greeted with

either mirth or pitty, sometimes both.

Any egalitarian

democrat would be dismayed by Modi’s extraordinary displays of public

narcissism. However, the scholar’s job is as much to understand as to judge.

The cold, hard fact is that, like Indira Gandhi in the early 1970s, Modi is

unquestionably very popular and one could mention the following six..

First, Modi is

genuinely self-made as well as extremely hardworking. Folklore has it that he

once sold tea at a railway station—while some have questioned the veracity of

this particular claim, there is no doubt that his family was disadvantaged in

terms of caste as well as class. He takes no holidays and is devoted 24/7 to

politics, which can be represented as being devoted 24/7 to the nation.

Second, Modi is a

brilliant orator, with a gift for crisp one-liners and an even greater gift for

mocking opponents. He is uncommonly effective as a speaker in the language most

widely spoken in India, Hindi, and is even better in his native Gujarati.

Third, in terms of

his background and achievements, Modi compares very favorably to his principal

rival, Rahul Gandhi, of the now much-decayed Congress party. Gandhi has never

held a proper job or exercised any administrative responsibility. (On the other

hand, Modi was chief minister of a large state, Gujarat, for more than a decade

before he became prime minister.) Gandhi takes frequent holidays, and he is an

indifferent public speaker. (English, spoken or understood by only 10 percent of the population, remains his first language.)

He is a fifth-generation dynast. In all these respects, Modi shines by

comparison.

Fourth, as Hindu

majoritarianism increasingly takes hold in Indian politics and society, Modi is

seen as the great redeemer of Hindus and Hinduism. Reared in the hard-line Hindu chauvinist organization Rashtriya

Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), Modi frequently mocks the past rulers of India, both

Muslim and British. He speaks of rescuing the country from “thousands of

years of slavery” and

ushering in India’s much-delayed national and civilizational renaissance.

Fifth, Modi has at

his command a massive propaganda machinery sustained by the financial resources

of his party and government and by 21st-century technology. An early and

influential use of Twitter and Facebook, Modi has had his party use both as

well as WhatsApp to build and enhance his image. (The prime minister also has

his personalized and widely subscribed-to Narendra Modi App.) Modi’s face, and usually no other, appears on all

posters, hoardings, advertisements, and websites issued by or under the aegis

of the Indian government. Thus, he can use public resources to burnish his

personality cult far more widely and effectively than elected autocrats

elsewhere (even Putin).

Sixth, Modi is an

exceptionally intelligent and crafty man. While mostly an autodidact, in 14

years as a party organizer and 13 as chief minister of Gujarat, he assimilated

a huge amount of information on all sorts of subjects—economic, social,

cultural, and political. He can speak with apparent authority on the benefits

of solar energy, the dangers of nuclear warfare, the situation of the girl

child, developments in artificial intelligence, and much else. He is also

extremely shrewd in manipulating the political discourse within his party, and

the country at large to favor himself and diminish his rivals or opponents.

(The likes of Trump and Bolsonaro are mere demagogues in comparison.)

The third democratic

institution that has rapidly declined since 2014 is the press. In a democracy,

the press is supposed to be independent; in India today, it is pliant and

propagandist. In eight years as prime minister, Modi has not held a single

press conference involving questions from the media. He conveys his views by

way of a monthly monologue on state radio and by the occasional interview with

a journalist known to be favorable to the regime; these conducted with a

cloying deference to Modi. Furthermore, because most of the country’s leading

newspapers and TV channels are owned by entrepreneurs with other business

interests, they have quickly fallen into line, lest, for example, a chemical

factory also owned by a media magnate does not get a license or an export

permit. (Indian media also depend heavily on government advertising, another

reason to support the ruling regime.) Prime-time TV exuberantly praises the

prime minister and relentlessly attacks the opposition—so much so that a term

has been coined for them, godi media.

These two words require a more extended translation in plain English—perhaps

“the media that takes its instructions from and obediently parrots the line of

the Modi government” would do. Many independent-minded journalists have been

jailed on spurious charges related to their work; others have had the tax

authorities set

on them.

The fourth key

institution that has become less autonomous and independent since May 2014 is

the bureaucracy. In India, civil servants are supposed to work following the

constitution and be strictly nonpartisan. Over the years, they have become

steadily politicized, with many officials tending to side with a particular

political party or even with a particular politician. However, since 2014,

whatever independence and autonomy remained have been completely sundered. In

choosing his key officials, Modi places far greater emphasis on loyalty than

competence. Every ministry now has a minder, often an individual from the RSS,

to ensure that, when a senior civil servant retires, his or her replacement

will have the right vichardhara, or

ideology.

Furthermore, state

agencies have been savagely let loose to intimidate and tame the political

opposition. (According to a recent report by the Indian Express, 95 percent of

all politicians raided or arrested by the Central Bureau of Investigation since

2014 have been from opposition parties.) These raids are held out as a warning

and inducement, for a slew of opposition politicians have since joined the BJP

and had cases against them withdrawn.

Finally, in recent

years, the judiciary has not fulfilled the role accorded it by the

constitution. District and provincial courts have been very energetic in

endorsing state actions that infringe on the rights and liberties of citizens.

More disappointing, perhaps, has been the role of the highest court of the

land. The legal scholar Anuj Bhuwania has gone so far as to speak of the “complete

capitulation of the Supreme Court to the majoritarian rule of Prime Minister

Narendra Modi.” It has delayed the hearing of crucial cases; even when it does,

it tends to favor the arbitrary use of state power over protecting individual

freedoms. As Bhuwania writes in Scroll.“During the Modi period, not only has the

court failed to perform its constitutional role as a check on governmental

excesses, it has acted as a cheerleader for the Modi government’s agenda. Not

only has it abdicated its supposed counter-democratic function as a shield for

citizens against state lawlessness, but it has also actually acted as a

powerful sword that can be wielded at the behest of the executive.” He writes,

the Supreme Court “has placed its enormous arsenal at the government’s disposal

in pursuit of its radical majoritarian agenda.”

They were occasionally

(and sometimes more than occasionally) timid or subservient to the party in

power. There was no golden age of Indian democracy. However, since May 2014,

these institutions have lost even more—one might say far more—of their

independence and autonomy and are now in thrall to Modi and his government.

The Gujarat Riots

The early history of Gujarat is posted here.

Let’s kill Gandhi

Tushar A. Gandhi

describes in his book ‘Let’s kill Gandhi !’ that communal violence was unheard

of in the state of Orissa before Gandhi was killed by Nathuram Godse--an activist of the Hindu Mahasabha whose leader went

on to found the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh

(RSS).

Later the RSS would

support the Bharatiya Janata

Party (BJP) and

its chosen representative, later Prime Minister A. B. Vajpayee started his

career as RSS organizer.

Today Godse is something of a hero on BJP and RSS

websites.

As for Modi a

problem started when in 1985 the RSS assigned Modi to the BJP, when Modi

rose to the rank of its General Secretary. Modi then was appointed Chief

Minister of Gujarat in 2001 where his administration has been considered

complicit in the 2002 Gujarat riots.

The turning point of

the dispute was the planting of an idol of an infant Ram in the Babri Masjid on

the night between December 22 and 23, 1949. It was this conversion of the

mosque into a temple that led to what initially was a legal battle.

Many blamed Modi for

doing little or nothing to stop the violence. (In 2005, Modi was even denied a

U.S. visa for this reason). Senior Gujarat police officer Sanjeev Bhatt has

told the Supreme Court in an affidavit that chief minister Narendra Modi had

asked police officials to "let Hindus vent out their anger against Muslims

following the Sabarmati Express train burning incident in Godhra on February

27, 2002."

By the time Modi was

appointed Chief Minister in 2001 Gujarat and had become a kind of laboratory

for the spread of BJP Hindu Nationalism where hard-line

Hindus called for the Babri mosque to be destroyed. It was built on the exact

spot in Ayodhya where Hindu faithful believe a Hindu

god, Lord Ram, was born. Some believe a Hindu temple stood there centuries

earlier, though it's a matter of

debate among

archaeologists.

Many blamed Modi for doing

little or nothing to stop the violence. (In 2005, Modi was even

denied a U.S. visa for

this reason). Senior Gujarat police officer Sanjeev Bhatt has told the Supreme

Court in an affidavit that chief minister Narendra Modi had asked police

officials to "let Hindus

vent out their anger against Muslims following the Sabarmati Express train

burning incident in Godhra on February 27, 2002."

Claiming that the

riots were systematically planned by a political party with the help of

criminal elements, Bhatt said, the riots could have been averted had timely

action been taken.

"Such things

(mass killing) will continue, unless and until we raise our voice. First 1993

riots in Mumbai, then the 2002 riots took place in Gujarat. If we keep quiet

now, then things will not change. If Muslims were killed now (in Godhra riots),

Hindus may be killed tomorrow," Bhatt said.

Shankar Menon, a former bureaucrat of

Maharashtra government, said, "When I had spoke to the

then deputy collector in Gujarat, the collector told me that Modi had asked to

take three Muslims lives for each Hindu."

The turning point of

the dispute was the planting of an idol of an infant Ram in the Babri Masjid on

the night between December 22 and 23, 1949. It was this conversion of the

mosque into a temple that led to what initially was a legal battle.

By the time Modi was

appointed Chief Minister in 2001 Gujarat and had become a kind of laboratory

for the spread of BJP Hindu Nationalism where hard-line Hindus

called for the Babri mosque to be destroyed. It was built on the exact spot

in Ayodhya where Hindu faithful believe a

Hindu god, Lord Ram, was born. Some believe a Hindu temple stood there

centuries earlier, though it's a matter

of debate among archaeologists.

In the late 1980s,

calls for the Babri mosque's destruction grew louder when Hindu nationalists -

those who believe India should be a Hindu nation - were gaining influence. Then

in 1992 RSS members were among those wielding hammers back in 1992 at the Babri

mosque. Footage from that day shows mobs rampaging through

Muslim homes and businesses in Ayodhya.

They were occasionally (and sometimes more than

occasionally) timid or subservient to the party in power. There was no golden

age of Indian democracy. However, since May 2014 these institutions have lost

even more—one might say far more—of their independence and autonomy and are now

in thrall to Modi and his government.

No Golden Age Of Indian Democracy

They were occasionally (and sometimes more than

occasionally) timid or subservient to the party in power. There was no golden

age of Indian democracy. However, since May 2014 these institutions have lost even

more—one might say far more—of their independence and autonomy and are now in

thrall to Modi and his government.

Two additional

features of personality cults in such partially democratic regimes. First, they

tend to promote crony capitalism, with a few favored industrialists making

windfall gains owing to their loyalty and proximity to the leader and his

party. The second is that they tend to promote religious or ethnic

majoritarianism. The majority ethnic or religious group is said to represent

the true essence of the nation, and the leader is said to embody, with singular

distinction and effectiveness, the essence of this majority group. On the other

side, religious or ethnic minorities, such as Kurds in Turkey, Jews in Hungary,

or Muslims in India, are considered disloyal or antithetical to the nation.

Majoritarian arguments singling out minorities for harassment or stigmatization

are rife on social media, made often by ruling party legislators and, on

occasions when he feels politically threatened, by the leader himself.

Democratic

institutions are far weaker in India than in the U.K. or the United States. And

as an individual, too, Modi represents a far greater threat to his country’s

democratic future than Trump ever could. For one, he has been a full-time

politician for far longer than they have been, with much greater experience in

how to manipulate public institutions to serve his own purposes. Second, he is

far more committed to his political beliefs than Johnson and Trump are to

theirs. While Trump are consumed almost wholly by vanity and personal glory,

Modi is part narcissist but also part ideologue. He lives and embodies Hindu

majoritarianism in a much thoroughgoing manner than Trump

lives white supremacy. Third, in the enactment and fulfillment of his

ideological dream, Modi has as his instrument the RSS, whose organizational

strength and capacity for resource mobilization far exceed any right-wing

organization in the U.K. or the United States. Indeed, if it lasts much longer,

the Modi regime may come to be remembered as much for its evisceration of

Indian pluralism as for its dismantling of Indian democracy.

Conclusion

In Freedom House’s

political and civil freedom rankings, India was among the countries with

the largest

declines in the last

decade, dropping from “Free” to “Partly Free” in 2021. In the Cato

Institute’s Human Freedom

Index, India fell from

75th in 2015 to 119th in 2021. In Reporters Without Borders’ World Press

Freedom Index, India

fell from 140th in 2013 to 150th in 2022. Finally, in the World Economic

Forum’s most recent Global Gender

Gap Report,

released in July, India ranked 135th out of 146 countries in overall score and

lowest (146th) when it came to health and survival.

For updates click hompage here