By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

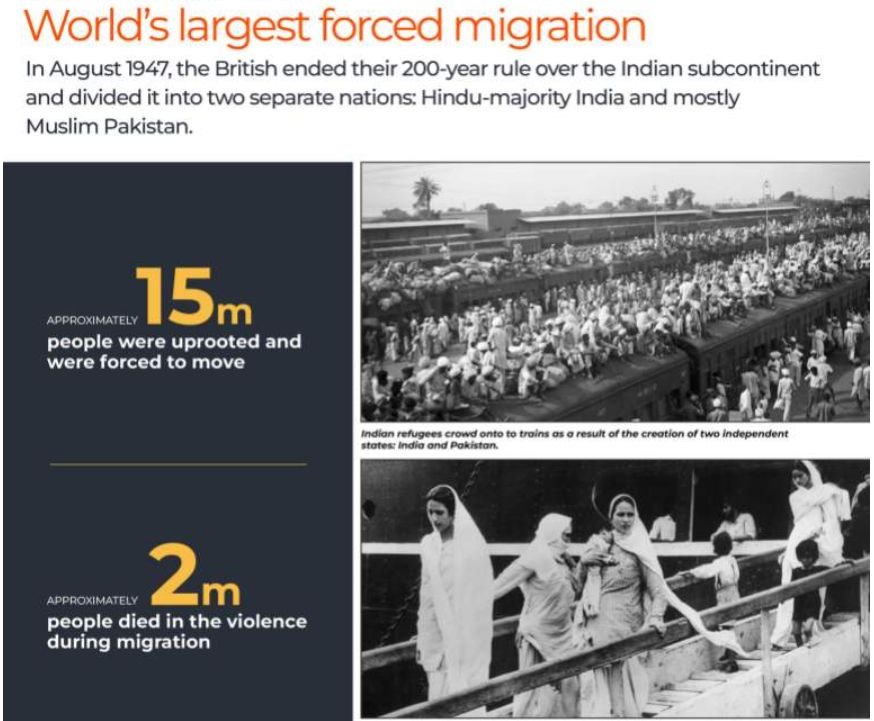

The 1947 Partition created two newly-independent states - India and

Pakistan - and triggered perhaps the most significant

movement of people in history, outside war and famine. About 12 million

people became refugees. Between half a million and a million people were killed

in religious violence.

The partition of India in August 1947 was, to a degree, related to

British concerns about the possibility the USSR could acquire influence.

The USSR's victory over Germany in 1945 had increased Joseph Stalin's

ambitions, just as he had already started to do so in Eastern Europe. To the

Soviet Union's southern border lay the region of the Persian Gulf with its oil

fields - the wells of power - that were of vital interest to the West.

Already in the summer of 1940, Leopold Amery, the secretary of State

for India, wrote a (secret) letter to Lord Linlithgow, the viceroy, in which he

noted: If our [British] tradition is freedom-loving and our domestic

development centuries ahead of the continent, that is large because we are an

island. If the Prussian tradition is one of militarism and aggression, it is

largely because Prussia had never had any natural frontiers. Now India has a

very natural frontier at present. On the other hand, within herself, she has no

natural or geographic or racial, or communal frontiers - the north-western

piece of Pakistan would include a formidable Sikh minority. The north-eastern

part has a Muslim majority so narrow that it's set up as a State or part of a

wider Muslim State seems absurd. Then there is the large Muslim minority in the

United Provinces, the position of Muslim princes with Hindu subjects, and vice

versa. An all-out Pakistan scheme seems to be the prelude to continuous

internal warfare in India.1

Thus, Britain, in 1940, hoped to stay in India for many decades.

Therefore, its leaders had no interest in creating a sovereign state of any

denomination in the subcontinent, Muslim, Hindu, or any other at the time.

The only person who ever suggested the partition of India before Jinnah

was inspired to do so by the British in 1940 was one thirty-six-year-old

individual named Rahmat Ali (1897-1951). In 1933 he published a

pamphlet from Cambridge in England titled 'Now or Never. In this pamphlet, he

proposed the creation of a separate sovereign state in the north-western region

of India. He also coined the word 'Pakistan'* for it. But the idea was so

unpopular among Muslims that he was ignored.

Stanley Wolpert, the well-known American historian, in his book ]innah of Pakistan, speculates whether the die-hard

British Conservatives might not have inspired even Rahmat Ali's ideas.

Churchill and his friends were dead set against an All-India Federation that

the British Government was considering in the wake of the Round Table

Conferences of the early 1930s. They feared that whatever the safeguards

incorporated in such a federn, it might encourage the

Indian parties and religious groups to work together and start India's slide

towards political unity and self-rule. They would rather have three mutually

antagonistic entities emerging in India: 'A Muslimstan,

a Hindustan and a Princestan', as Viceroy for India

Lord Linlithgow to Jinnah on 13 March 1940 and later by Churchill to the next

Viceroy Lord Wavel. Such a trifurcation would 'institutionalize'

differences among the Muslims, the Hindus, and the princes and would enable

Britain, by playing one against the other, to rule for decades to come.

When the news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was received in

London on the evening of 7 December 1941. Winston Churchill records in his

memoirs his feelings of relief and elation that Japan had, by this act, drew

the United States into the war: 'So we had won, after all, Britain would live.

The Commonwealth and Empire would live. We should not be wiped out. Our history

would not end... Being saturated and satisfied with emotion and sensation, I

went to bed and slept the sleep of the saved and thankful.1

On waking up, his first act was to plan to go to Washington to review

with President Franklin Delano Roosevelt the whole war plan in the light of

reality and new facts as well as the problems of production and distribution.

It was during this visit, recounts Churchill, that Roosevelt' first raised the

Indian problem with me on the usual American lines', meaning on anti-'Empire'

lines. He continues: 'I reacted so strongly at such length that he never raised

it verbally again.'2

Immediately after returning to London, worried that Roosevelt would

return to the Indian situation, Churchill asked the War Cabinet to develop a

policy to forestall American pressure for self-government in India. As he

writes: 'The concern of the Americans with the strategy of a world war was

bringing them into touch with political issues on which they had strong

opinions and little experience... In countries where there is only one race,

broad and lofty views are taken on the color question. Similarly, states

which have no overseas colonies or possessions are capable of rising to moods

of great elevation and detachment about the affairs of those who have:'4

Roosevelt's interest in India was based on enlisting popular support there

against the advancing Japanese, ensuring India's freedom and the subsequent

building up, after the war, of a post-colonial order in Asia.

Britain's planned strategy succeeded brilliantly from there on.

Pakistan, together with Iran, Iraq, Turkey, and Britain, joined the Baghdad

Pact and later, CENTO, which the US also joined, to form a defense barrier

against Soviet ambitions in the Middle East. In 1954 Pakistan entered into a

bilateral pact with Britain's ally, the USA, and, in 1958, provided an air base

in Peshawar to the CIA for U-2 spy planes to keep a watch on military

preparations in the Soviet Union. Then, in the 1970s, Pakistan helped the US

establish relations with China to pressurize the Soviet Union from the east.

And in the 1980s, Islamabad provided the forward base from which the US could

eject the Soviet forces from Afghanistan, precipitating the collapse of the

USSR and altering the world balance of power.

On the other hand, the 'Pakistan strategy' did not prevent the Soviet

Union from reaching out to India. This it did by supporting India against

Pakistan, which had the backing of the Western powers, in Kashmir, in the

1950s. In August 1971, an Indo-Soviet treaty with a defense-related clause

was signed. This treaty restrained China from interfering in the forthcoming

Indo-Pakistan war on Bangladesh. Treaties may be like flowers and young girls

that last while they last, as Charles de Gaulle said, but the process of India

purchasing Soviet arms on rupee payment and the barter that started in the

early 1960s has become an important and longstanding feature of Indo-Soviet

relationship. Would the collaboration between these two countries have

developed but for partition?

Partition also helped China extend its influence right up to the mouth

of the Persian Gulf - via Pakistan. In 2004, hundreds of Chinese were building

a port in Gwadar in Baluchistan, at the mouth of the Gulf. What

facilities China will get from Pakistan remain undisclosed. To begin with,

China befriended Pakistan so that the latter would not permit Islamic

separatist influences to reach the Muslims of Sinkiang through the

British-built road from the subcontinent via northern Kashmir to Kashgar - 'the main artery into Central Asia,' as

Ernest Bevin once described it to George Marshall. Since the 1980s, China has

helped Pakistan neutralize the larger Indian conventional force by supplying it

directly and through North Korea's nuclear weaponry and missiles. One may

indeed ask: Would the 1962 Sino-India clash have occurred had India remained

united? Would the Indian subcontinent have been nuclearized in the twentieth

century but for partition?

The unobtrusive but steady pressure exerted by the US on Britain

in favor of India's independence and unity from 1942 to 1947 has been

(strangely) neglected by historians so far. Roosevelt made several attempts to

persuade Churchill to grant self-government to India after the fall of

Singapore but in vain. As soon as an Interim Government under Jawaharlal Nehru

was formed in 1946, the US recognized it and sent an ambassador to Delhi to

consternate the British. The Americans thereafter advised Britain to keep India

united. They feared that India's Balkanization would help the communists. Only

after March 1947, when the Congress Party accepted the division of the Punjab

and Bengal, did the US find itself helpless to do any more. 'The Congress

leaders had abandoned the tenets which they supported for so many years in the

campaign for united India', wired the American Embassy in Delhi to Washington.

The US pressure on Britain led to one predictable result. To find it

off, Churchill, in 1942, played the 'Muslim' or the 'Pakistani' card: that it

was not British reluctance to grant self-government to India but the profound

differences amongst Muslims and Hindus on India's future that was creating the

problem. Such a move brought Jinnah's 1940 scheme for partition and his

two-nation theory center stage. The theory of 'the provincial

option', which created the constitutional channel by which partition could be

put into effect, was concocted in London in 1942.

That by 1943, India had become an essential adversarial factor in

Anglo-US relations is not well known. This factor could have been liquidated by

Indian disenchantment with America, vice versa, or both. The record shows that

Mountbatten, Krishna Menon, and Attlee worked on Nehru to raise his suspicions

about the US motives in Asia. Side by side, British speakers and diplomats

propounded the idea in the US that the Indian Muslim had better imbibed the

Western legacy and was a more reliable partner than the feeble and unreliable

Hindu. The Indian leaders' ambitious foreign policy after independence,

combined with their inexperience, took no time to collide with the Americans'

impatient and demanding nature, mixed with their ignorance about India.

The Americans, to begin with, showed more understanding of India's

position on Jammu and Kashmir than did Britain. Throughout 1948, the US

insisted that J&K's accession to India could not be brushed aside unless it

lost the plebiscite that India itself had offered. Meanwhile, Pakistani forces

that had entered the state had to be withdrawn. This US stand prevented

J&K's accession to India from being negated by the UN Security Council at

the British behest. But while Britain was able to maintain good relations with

India, the neutral Americans were cast as the villains of the piece. This was

largely due to Nehru's basic distrust of capitalist America, his faith in

socialist Britain, and the personal ties that the Mountbattens had

developed with him.

To bring to light an important but ignored historical truth is

worthwhile. This is all the more appropriate because India has never recognized

the goodwill that the US showed for India's independence and unity during the

end game of the Empire. Admittedly, today, given Russia's retreat from Central

Asia and the growing mutual concern about terrorism and political Islam, a new

chapter is opening up in Indo-US relations.

The story is also a cautionary tale for Indians. High ideals inspired

the leaders of the Congress Party. They built up a broad-based all-India

organization without which the struggle for independence would not have been

possible. They revived the sagging morale and confidence of a fallen people,

contributing to 'India's great recovery', to use K. M. Panikar's phrase.

They devised instruments such as satyagraha (peaceful mass protest or

resistance), answering violence with non-violence. Such measures put moral

pressure on the democratic British people to push their government to recognize

India's legitimate demands. These were great achievements.

But the Indian leaders

remained plagued by the Indians' age-old weaknesses of arrogance,

inconsistency, often poor political judgment, disinterest in foreign affairs,

and questions of defense. Overconfidence made them ignore the dangers of

rejecting, from the Congress Party's fold (in the 1920s), the secular and very

able, though egocentric, Jinnah. They failed to include, after the party's

massive victory in provincial elections, in their governments, in 1937, those

Muslim League leaders who wanted to taste the plums of office. The British

archives reveal that in their negotiations with the viceroys in the

1940s, there was no consistency - without which there could be no success in

diplomacy or war - or indeed a clear, realistic policy. The Congress Party

resolution of 11 April 1942 rejected the Stafford Cripps offer that sought to

divide the country by giving the provinces the right to stand out but spoke

elsewhere of the right of units to break away from the Indian Union.4 In his

talks with Jinnah in September 1944, Mahatma Gandhi suggested district-wide

referendums in British provinces claimed by Jinnah, thereby accepting the

principle of some kind of partition.6 In his letter to Cripps of 27 January

1946, Nehru mentioned the possibility of the division of Punjab and Bengal.7

They could not even make up their minds on whether or not to accord priority

above all else to India's unity or to consider non-violence a higher duty.

One should also understand that during the first half of the 20th

Century (that is, until after 'independence' around 1950), social contact,

except with the princely order and some selected Indians, did not exist, even

between British and Indian officers in the Army. Indians were unwelcome in

train compartments occupied by Britishers even when they held valid tickets.

British clubs excluded Indians. Indians dismounted from their ponies or other

conveyances to salute the 'Sahib' if they crossed one on the road. That

Harcourt Butler, the governor of the United Provinces, sent a bottle of

champagne to the jail cell of Motilal Nehru, Jawaharlal's father, on

his first night in prison for participating in Gandhiji's civil disobedience,

in remembrance of the many drinks they had together, was an exception that

proved the rule.

Further, the onerous challenges of a worldwide empire required British

belief in their superiority and pre-eminence. This resulted in slogans like the

'white man's burden'. Christian missionaries who entered India in the

nineteenth century were sustained by donors back home, and it was only natural

for them to project the worst possible picture of those to be redeemed to

obtain funds. And sex, the great equalizer, lost its humanizing influence as

faster ships made it possible to bring out British wives to India. To protect

them, too, the race card had to be played to the full. In 1947, 50

percent of the senior civil services, 60 percent of police officers, and all

posts above lieutenant colonel in the Army were held by Britishers.

Below Nehru, Jinnah,

and Mountbatten:

Not mentioned in Alex Von Tutzemann's "Indian

Summer" (2007), for example, is that the Mountbattens

made it a rule that no less than 50 percent of those invited to their garden

parties, lunches, and dinners shortly before 'Independence' should be (Princely

in that case) Indians, when until then few if any, Indians had been invited to

such functions. He took an Indian aide-de-camp - the first ever appointed.

'These measures were not popular among a certain class of Europeans', he

reported. 'This was made clear when my younger daughter (Lady Pamela), standing

near two English ladies to whom she had not been introduced, heard one say to

the other: "It makes me sick to see this house full of dirty

Indians."7 London).

Most Indian leaders at the forefront of the independence movement

continued to be victims of the old legacy. They did not devote much thought

during the freedom struggle to external relations or how the country's

defense would be organized after independence had been achieved.

Resigning from governments in British provinces in 1939 and launching

the Quit India movement in 1942 proved counterproductive. For Nehru to include

Muslim League ministers in the Interim Government in September 1946, before the

League had entered the Constituent Assembly and agreed to stop 'direct action'

or terrorism, was another blunder. To prematurely declare in December 1946 that

India would become a republic while engaged in delicate negotiations with the

Attlee Government on a future settlement was a mistake. By the end of 1946,

they had been maneuvered into such a corner that if Sardar Patel had

not stepped forward 'to have a limb amputated, as he put it, and satisfy

Britain, there was a danger of India's fragmentation, as Britain searched for

military bases in the bigger princely states by supporting their attempts to

declare independence.

Protected by British power for so long and focused on a non-violent

struggle, the Indian leaders were ill-prepared, as independence dawned, to

confront the power play in our predatory world. Their historic disinterest in

other countries' aims and motives made things none the more accessible. They

had failed to see the British motivation for supporting the Pakistan scheme and

taking remedial measures. Nor did they understand that, at the end of the Raj,

America wanted a free and united India to emerge and to find ways to work this

powerful lever. Glaring mistakes were made in handling the Kashmir imbroglio.

For example, Alan Campbell-Johnson, the governor-general's press

attaché, wrote: Since returning to Delhi [from London] Mountbatten had seen

Gandhi and VP. [Menon] who were both favorably inclined to the

invocation of [the] UNO. And today [11 November 1947], he had a further talk

with Nehru, whose attitude to the idea is now less inactive than it was at

Lahore [at the meeting between Nehru and Liaqat Ali Khan three days earlier].9

Earlier, in September 1947, Gandhiji approached Mountbatten with the

suggestion that Attlee is requested to mediate between India and Pakistan to

avert a clash between the two countries as a result of the conflagration in

Punjab. Gandhiji, since a large majority of British Officers were not in the

Indian but what was now the Pakistani armies, wanted Attlee to ascertain 'in

the best manner he knows who is overwhelmingly in the wrong and then withdraw

every British Officer in the service of the wrong party.8

Attlee had parried the request: ‘When political tragedies occur’, he

informed Gandhiji, ‘how seldom it is that, at all events at the time, the blame

can be cast, without a shadow of doubt substantially on one party alone.9

Gandhiji was very disappointed. Mountbatten’s comment on Gandhiji’s proposal

(in a letter to Lord Ismay) was as follows: ‘He seems to ignore the fact

that if we expelled Pakistan from the Commonwealth, Russia would step in. Much

later, Mountbatten wrote to Gandhiji: ‘An alternative means is to ask UNO to

undertake this inquiry, and you would have no difficulty in ge‘ting

Pakistan to agree to this.’ (Ibid. Mountbatten to Gandhiji, 29 September 1947.

Nothing came of this proposal, but this was how a reference to the UN came to

be broached.

Vallabhbhai Patel and Mountbatten had worked together on India’s

division and the princely states’ integration into the Indian dominion. Still,

after independence, Mountbatten found him less tractable than Nehru.

Mountbatten was aware of the growing rift between Nehru and Patel. When Nehru

had submitted to him the list of independent India’s first cabinet in August

1947, according to H.V. Hodson, Patel’s name was missing from it. Mountbatten,

on v.P. Menon’s prompting, made Nehru

include Patel in the cabinet. V.P. Menon argued that an open clash in

the Congress Party Working Committee between the two might result in Nehru’s

defeat. For this, see H.Y. Hodson, The Great Divide: Britain-India-Pakistan

(Oxford University Press edition, Delhi, 2000, p. 381). It should be noted that

Hodson was meticulous in his research and had access to Mountbatten while wri’Ing his book The Great Divide in the 1960s. Hodson said

that the Mahatma possibly wanted Patel to lead the recast Congress Party he was

planning.

One of the other problems at that time concerned the division of

the assets of undivided India between the two dominions. The issue’s crux was

transferring the second installment of Rs 550 million (equal to about half a

billion US dollars today) to Pakistan. (Until then, only the first installment

of Rs 200 million had been transferred.) Nehru had told C. Rajagopalachari on

26 October 1947: ‘It would be foolish to make this payment until this Kashmir

business had been settled.’ 9

Mountbatten has recorded how he convinced Gandhiji of the validity of

the Pakistani claim: I told him that I considered it to be unstatesmanlike and

unwise (not to pay). The documents also bring out the anti-Congress Party and

anti-Hindu sentiments of the British officers serving in the country even as

they prepared to quit India. Most such officers, who stayed on after

independence, went over to serve Pakistan and did their damnedest against

India.

Was it possible to have

avoided partition by 1946-47? It may be worth dwelling on this question for a

moment.

Besides the strategic factor, there were other reasons for Britain

to favor partition. One was the doubt in the British mind that India

might not have a good chance of surviving as an independent state. A top-secret

appreciation, prepared in the Commonwealth Relations Office soon after British

withdrawal, elaborates this doubt. Factors such as India's heterogeneous

population, the North-South divide, the communal problem, the unruliness of the

Sikhs, and the policy of the Indian communists to spread dissension are cited

in this context. One can't say how far Attlee, or how many of his colleagues,

accepted this analysis. But notions of India's instability were deeply embedded

in the thinking of British officials, senior Conservative politicians, and many

journalists, including editors of newspapers. In the circumstances, it is not

surprising that the British would hesitate to put all their eggs in the Indian

basket.

There was another reason for the British tilt towards the creation of

Pakistan. I have referred to the hatred for Indian leaders in general and the

Hindus in particular that most British civilians and military men in India had

started to feel by 1947. The nationalists' non-cooperation in the war effort

had created deep distrust for them in Britain and several countries of the

British Commonwealth, particularly in South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.

Therefore, the emotion among the English in favor of Pakistan was

very great. (It has not subsided entirely even to this day.)

The Indians, too, faced

difficulties in cooperating with Britain.

The British support for the Muslim League as well as for the Pakistan

scheme had created a general and widespread suspicion of their intentions among

the public. Besides, there were specific points of disagreement. Jawaharlal

Nehru was willing to cooperate with Britain on several issues, including that

of supporting the Commonwealth concept, which, he believed, would help to

balance American influence in the world. But he was opposed to getting

entangled in any schemes to contain or confront the Soviet Union and China.

Also, he was bent on fighting European colonialism and apartheid, even if his

stance embarrassed Britain and its friends. A possibility that greatly excited

him was the opportunities independence would offer India to mediate for peace

between the West and the East and, in so doing, strike out a new path in world

affairs. By appealing to the deep-felt urges of mankind for freedom, equality,

and peace, he believed that India could develop a diplomatic reach, which would

be as effective in influencing world events as power politics and military

strength. These concepts, of course, would be difficult to marry with British

ideas and were unlikely to persuade Britain to abandon the Pakistan scheme,

inexperienced in foreign affairs, and far too vain' was the British High

Commission's (in India) top-secret assessment of Nehru. (This was written by

Frank Roberts, the acting high commissioner. It fell into Indian hands and

crossed my desk as private secretary to Sir Girja Shanker Bajpai, the

secretary-general of the Ministry of External Affairs.)

Many Indians, by and large, do know that the Imperial power

supported the partition plan to weaken India so that it remained dependent on

Britain even after independence. This is, however, only half the truth. The

British left no stone unturned to push their allies, the princes - whose

territories constituted one-third of the Raj - into the arms of India, except

for Jammu and Kashmir. This step helped unify disparate and fragmented parts

into a cohesive country. Suppose the British were out to weaken India. Why

should they have done this or left the Andaman and Nicobar as well as

the Laccadive Islands in Indian hands, which increased India's naval

reach in the Indian Ocean? Or, why should they have whittled down Jinnah's

territorial demands to the minimum required for Britain to safeguard

its defense requirements?

The English and people abroad generally believed that India was divided

because Hindus and Muslims could not live peacefully together in one country,

and a separate state - Pakistan - needed to be carved out of India for the

Muslims. But the fact is that such a division of the two communities was never

made. Nearly thirty million Muslims, or a third of the total Muslim population

of India, were excluded from Pakistan. These Muslims residing in Indian

provinces, in which they were minorities, were the only ones who could be said

to be vulnerable to Hindu pressure or domination. The creation of Pakistan was

justified to protect them, but they were left behind in India." The areas

in Pakistan (the NWFP, West Punjab, Baluchistan, and Sind) had Muslim majorities

with no fear of Hindu domination and were ruled by Muslim governments. Indeed,

the NWFP and Punjab had governments opposed to Jinnah's Muslim League. But they

were placed in Pakistan.

However, these four provinces/units had one common feature: the British

chiefs of staff considered their territories of absolute importance for

organizing a defense against a possible Soviet advance toward the

Indian Ocean.

Partition was a politico-strategic act. It was not to 'save' Muslims

from Hindus, nor was it to weaken India. 'Everyone for home; everyone for

himself.'

The British adopted the policy of divide and rule in India after the

bloody revolt or the Great Mutiny of 1857. This was a policy to control

Indians, not to divide India. The latter question arose when the British

started to plan their retreat from India, the facts about which are the subject

of this story. If the impulse was Churchill's, Attlee implemented the scheme.

Working behind a thick smoke screen, he wove circles around Indian leaders and

persuaded them to accept partition.

The belief that the Cabinet Mission plan sought to avoid, or would have

succeeded in avoiding, the partition is mistaken. This plan would have

intensified communal tension and most probably Balkanized India. However, it

served HMG's purpose as follows. It shocked Jinnah that the Attlee Government

might move away from partition and prepare the ground for him to accept the

smaller Pakistan. The entry of the Congress leaders into the Interim Government

kept them from revolting; it softened them up to ultimately accept the

Wavell-Attlee plan. The exercise served British public relations; it made the

United States impression that Britain was working for Indian unity.

The plan for the smaller Pakistan was not worked out by Mountbatten in

1947, as generally believed, but by Lord Wavell in 1945, who submitted its

detailed blueprint to London in February 1946. Mountbatten implemented the plan

by persuading the two main Indian parties to accept the same. Advancing the

date of British departure from June 1948 to August 1947 is often blamed for the

chaos and killings in Punjab. The date was advanced after the Congress Party,

in May 1947, agreed to accept the transfer of power on a dominion status basis,

provided Britain pulled out of India forthwith. Even temporarily, the Indian

acceptance of dominion status was important for Britain. ('The greatest

opportunity ever offered to the Empire.') It would facilitate the passage of the

Indian Independence Bill in the British Parliament by appeasing the

Conservative opposition. It would prove to the world that India had willingly

accepted the partition; otherwise, why should it agree to remain a British

dominion? It would gain time to persuade Nehru and his friends to abandon their

commitment to leave the British Commonwealth.

Penderel Moon, civil servant, and historian who was on the spot, has

written: 'The determination of the Sikhs to preserve their cohesion was the

root cause of the violent exchange of populations which took place, and it

would have operated with like effect even if the division of Punjab had been

put off another year.' Admittedly, the Muslim attacks on Sikh farmers in the

villages around Rawalpindi in March 1947 confirmed this community's worst fears

that the Muslim League was out to cleanse West Pakistan of non-Muslims, which

happened. However, Linlithgow and Wavell cannot escape the responsibility for

the Punjab massacres. They ignored the warnings of their governors, Henry Craik

and Bertrand Glancy that strengthening Jinnah's Muslim League in Punjab at the

expense of the Muslims of the Unionist Party, who were opposed to partition -

Shaukat Hayat used to call it 'Jinnahstan' - would

result in a blood bath in the province. Wavell did forward Glancy's warning to

London, but the policy to build up Jinnah as the sole spokesman of the Muslims

continued.

The view that Britain, by staying on longer, might have avoided the

Punjab troubles ignores the fact that the British neither had the troops nor

the administrative capacity to control events in India by the summer of 1947.

At least the vigor and speed with which Lord Mountbatten acted had the merit of

confining the conflagration to Punjab.

The British focus was no doubt on Pakistan as a

future defense partner in the Great Game, but India too had its

value. If it remained in the British family of nations, i.e., in the

Commonwealth, this retention would add to British prestige and influence in the

postwar world. How Mountbatten juggled the above two British goals was

none-too-easy a feat. While viceroy of India, he prized away the North West

Frontier Province from the Congress Party's control and, while India's

governor-general after independence, he restrained it from occupying the whole,

or more areas, of Kashmir. This made it possible for Pakistan to be formed as

a defense bastion. Simultaneously, he was able to build bridges

between the British and India, which led to the latter remaining a member of

the British Commonwealth.

The view that Mountbatten helped India to gain Kashmir by persuading

Sir Cyril Radcliffe to allow parts of the Muslim-majority areas of Gurdaspur

district (in Punjab) to India is not well founded. A fair-weather road through

this district was the only route connecting the state with India. But it was

Wavell's blueprint for Pakistan, sent to London on 6 February 1946, which has

to be studied in this context. The allotment had nothing to do with Kashmir or

Mountbatten. Wavell had recommended:

In Punjab, the only Muslim-majority District that would not go into

Pakistan under this demarcation is Gurdaspur (51 percent Muslim). Gurdaspur

must go with Amritsar for geographical reasons, and Amritsar, being [the]

sacred city of Sikhs, must stay out of Pakistan.

Mountbatten continues to receive flak in Britain, Pakistan, and India.

Some British frustration at India's independence ('Of course, he lost if), not

unnaturally, got rubbed off on the man who handed over power. The ex-viceroy,

in his old age, talked a bit too much - about his success in India - which

played into his detractors' hands, with India being vilified in the process.

His achievements for his country were very great, and as they say in England:

Good Wine Needs No Brush!

Regarding the princes, unless some organic relationship could be

established between the Central Government and the princely states, as was done

through the process of accessions - into which the princes were no doubt

stampeded by Mountbatten - a much worse fate awaited them. Ninety percent of

the princely states were too small to resist agitators entering from the Indian

or Pakistani provinces and overrunning them, threatening their rulers' lives

and property. If some bigger states tried to break away by declaring

independence, they would not have succeeded because Britain was not in a

position to come to their aid, and the United States was against the further

Balkanization of India. The accessions saved the princely order, if not the

princely states. They laid the foundation for a peaceful revolution. (It is

another matter that the British paid scant regard to solemn treaties signed

with the princes, whereas they laid so much stress on their obligations to mere

declarations made in the British Parliament to safeguard minority rights. After

all, Pakistan would be a partner in the Great Game after they quit India; the

princes had outlived their utility.)

Many, including some prominent historians like Stanley Wolpert (today

2007), believe that Mahatma Gandhi remained opposed to partition till the

very end. His absenting himself from Delhi on Independence Day is often cited

as proof.

Britain's pro-Pakistan policy on Kashmir was based on its desire to

keep that part of its old Indian Empire, which jutted into Central Asia and lay

along Afghanistan, Soviet Russia, and China, in the hands of the successor

dominion that had promised cooperation in matters of defense. In the open

forum of the UN, Britain could not concede its pro-Pakistani stand. The

Americans, in their internal telegram, have left a record of Britain's

pro-Pakistani tilt on Kashmir. So also, the Kashmir imbroglio in 1947-48 proved

once more that all that happened during the end game of the Empire could not be

understood unless one keeps in view the overwhelming concern of the withdrawing

power, as it pulled out, to secure its strategic agenda.

In July 1947, Jinnah personally approached the Maharaja of Jodhpur and

the Maharaj Kumar of Jaisalmer and offered favorable terms to the

rulers of these wholly Hindu-populated states to accede to Pakistan. He also

approached the rulers of the Hindu-populated states of Baroda, Indore, and

others through the Nawab of Bhopal. Jinnah did so because he knew very well

that the affiliation of the princely states to one or the other dominion was

left entirely to their rulers by the same British act that created Pakistan. It

was not a Hindu-Muslim question. That is also why Pakistan accepted the

accession of the Nawab of Junagadh, a Hindu-majority state. It furthermore

would be wrong to believe that because Kashmir was 77 percent Muslim, its

people would, in 1947, have automatically wished to join Pakistan.

The NWFP, next door, was 95 percent Muslim but its people resisted the

Muslim League and British pressure and remained with the Congress Party till

1947, when this party's leaders, in a quid pro quo with the British, abandoned

them.

In 1947, the overwhelming majority of Muslims of the Valley of

Kashmir, where well over half of the people of the state lived, supported

Sheikh Abdullah and his National Conference Party. Whatever his other

ambitions, Abdullah was opposed to Pakistan. Similarly, Jammu and its Dogra

belt would have voted against Pakistan. The only Muslims of the state who would

have supported Pakistan in large numbers at that time were those living along

Pakistan's border in the Poonch-Mirpur area. But since Pakistan was created,

the communal virus has spread to large parts of the subcontinent. I can't say

how the Kashmiris would vote today. But, in 1947-48, the majority, in all

probability, would have supported the maharaja's accession to India. And

1947-48 is the pertinent date when considering the issue. In all fairness, the

existing position cannot be brushed aside.

The successful use of religion by the British in India to gain

political and strategic objectives was replicated by the Americans in

Afghanistan in the 1980s by building up the Islamic jihadis, all for the same

purpose of keeping the Soviet communists at bay. The Muslim League's 'direct

action' before partition in India was the forerunner of the jihad in

Afghanistan. However, Al-Qaida's attacks on the World Trade Center towers in

New York and the Pentagon in Washington on 11 September 2001 woke the West to the

dangers of encouraging political Islam.

The Pakistan Government created the Taliban movement in Afghanistan

through the Jamaat-iIslami, Pakistan, and their ISI

intelligence service. The preachings of the Jamaat's founder, Abdul

Al Mawdudi, a migrant from India, envisaged a

clash of civilizations and governments founded strictly on the tenets of

the Shariat; he counseled jihad against non-believers. These views echoed

in many Muslim lands; they influenced Osama bin Laden. Even after the US-backed

jihad in Afghanistan had succeeded, Pakistan continued to help the Taliban

train terrorists to fight non-believers in the name of Allah. Without

Pakistan's backing, it is doubtful whether Islamic terror could have spread so

far and wide in the world, despite Osama bin Laden, Saudi and Gulf

petrodollars, and Arab suicide bombers. The Americans are now taking steps

to rein in the export of terror from Pakistan. But the genie has escaped the

bottle. Some of the roots of the present Islamic terrorism menacing the world

are buried in India's partition.

The British brought the 'New Learning' to India and the notion of

separating religion from politics that had become the norm in Christian Europe

after the Renaissance. These features open the possibility for secularism -

anathema to orthodox Muslims - to take root among the Muslims of India and work

on a democratic constitution together with people of other faiths; indeed, for

India becoming a laboratory for enlightened Islam. At the same time, Western

social mores helped foster among the individualistic Hindus a greater sense of

responsibility for society and a feeling of brotherhood between man and man.

Shashi Tharoor, the writer speaking of Hindus, has asked: How can faith

followers without any fundamentals become fundamentalists? But lack of

parameters and a sense of social responsibility can lead to intolerance and

parochialism. The good done by the spread of British liberal ideas in India in

the nineteenth century was undone in the twentieth by British politicians and

viceroys, who introduced divisive policies such as separate electorates for

Muslims (besides, of course, selfserving economic

policies that taxed the farmers). British rule, to the end,

maintained its duality: the civilizing mission and extreme selfishness mixed

with cunning - though during its last days, 'the Raj was about neither plunder

nor civilization but rather survival', as Fareed Zakaria, the columnist, and

writer, has put it.

There is, of course, the view that partition averted a worse disaster

for India in the years to come. The past half a century has seen a phenomenal

rise in Islamic fundamentalism and the forces of political Islam. Such a

development has drawn and deepened fault lines within many states with mixed

populations of Muslims and others. Would it be possible in such circumstances

for the more than 500 million Muslims of an undivided India to settle down

peacefully under a democratic, secular constitution? Partition, by

compartmentalizing Muslim political power in the two corners of the

subcontinent, has weakened the jihadis and given time for the pressure

from economic globalization and the technological revolution sweeping

the world to overhaul or temper the intensity of the globalization of jihad and

political Islam and ensure peaceful co-existence in the subcontinent. Plus, the

awareness that it was global politics, Britain's insecurity, and the errors of

judgment of the Indian leaders that resulted in the partition of India might

help India and Pakistan search for some form of reconciliation at one point.

Colonel Elahi Baksh, the

doctor who attended Jinnah during the last phase of his illness in

August-September 1948 at Ziarat near Quetta, reported he heard his patient say:

'I have made it [Pakistan], but I am convinced that I have committed the

greatest blunder of my life.' This was also reported around the same time by

Liaqat Ali Khan, the prime minister of Pakistan, upon emerging one day from the

sick man's room after receiving a tongue-lashing, was heard to murmur: 'The old

man discovered his mistake. 'See Member of Parliament Dr. M. Hashim Kidwai's

letter printed in The Times of India, 27 July 1988, based on reports published

in Frontier Post, Peshawar, and Muslim India, New Delhi.

1. MSS/EUR F 9/5, S. No. 32, p. 190, Oriental and Indian

Collection, British Library, London.

2. Winston Churchill, Memories of the Second World War, Vol. 6,

War Comes to America, London, 1950, pp.209-10.

3. Ibid,p.188.

4. For details of the latter deal, see Narendra Singh Sarila,

The Shadow of the Great Game, HarperCollins, 2005, pp. 110-111.

5. Narendra Singh Sarila, 2005, p. 179

6. Sarila, 2005, p. 201

7. Quoted in Report on 'The Last Viceroyalty', Part A, Para 112,

OIC, British Library,

8. Broadlands Archives (BA), University of Southampton.

MBI/E/193/2.

9.Ibid. Message to Gandhiji from Attlee.

10. Alan Campbell-Johnson, Mission with Mountbatten, Delhi, 1994, diary

entry of 11 November 1947.

11. C. Rajagopalachari, a prominent Congress leader from South

India, succeeded Mountbatten as the governor-general of India.

For updates click hompage here