By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

How The International Economic Order Can Stop The

Russian War Machine And Strengthen The Economy.

On the morning of Sunday,

February 27, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen sat huddled in a secure room

with a group of other senior Treasury officials—including myself—to discuss

extraordinary economic and financial measures against the Russian Federation. A

few days earlier, Russia had invaded Ukraine, a stark and violent transgression

of international law. At the direction of U.S. President Joe Biden, the

Department of the Treasury had already imposed full blocking sanctions on

several of Russia’s largest banks, put in place Russia-wide export controls on

sensitive technologies, and sanctioned several Russian elites. It determined

that any Russian financial services firm could be a target for further

sanctions. But in response to Russia’s growing aggression, Biden was calling on

us to take further steps to cut the Kremlin off from the resources it needed to

pursue its illegal war.

Throughout the

weekend leading up to Sunday’s meeting, we had worked with U.S. allies in Asia

and Europe and our colleagues at the Department of State, the National Security

Council, and across the U.S. government to develop a new tranche of actions:

immobilizing Russia’s central bank assets, creating an international taskforce

to hunt down and freeze Russian assets around the world, and removing critical

Russian financial institutions from the global SWIFT messaging system. Many of

these steps were unparalleled in their scale and scope. But what was most

significant was the speed with which this international coalition coalesced

behind the actions. Within three weeks of Russia’s renewed invasion, more than

30 countries—including Australia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and the

members of the European Union and the G-7—joined with the United States to

counter Russia’s aggression.

There is a reason why

so many countries backed these sanctions. Today's international economic system

reflects the rules-based financial architecture the United States and its

allies collectively built after World War II to promote peace, prosperity, and

economic integration. This system was designed to reinforce these goals by

enabling participating states to prevent countries violating the system’s

principles from reaping its benefits. The Treasury Department’s efforts to

deter and, later, make it harder for the Kremlin to wage this war rested on the

ability of the United States and its allies and partners to leverage their

positions at the system’s center. It is no accident that the coalition includes

the issuers of the world’s major convertible currencies, most of the world’s

key financial centers, and more than half of the global economy.

These efforts are

succeeding. The bravery and determination of the Ukrainian people, aided by

tens of billions of dollars in security and economic assistance from the United

States and its allies and partners, have been paramount in Ukraine’s valiant

defense against Russia. But economic sanctions have played a critical

supporting role, as well. Over the last ten months, Washington, its allies, and

partners have denied Russia’s key financial institutions access to the

infrastructure that powers the global financial system and cut Russia off from

the imports and advanced technologies essential to modern economic

production.

Multilateralism has

been decisive in the effectiveness of these economic measures. After the United

States imposed sanctions on Russia for the 2014 invasion of Crimea, Moscow

spent eight years working to limit its exposure to the U.S. financial system,

hoping to insulate Russia’s economy from the impact of future U.S. sanctions.

But although Russia could reduce its exposure to the United States and the

dollar, it could not avoid the international economic system and the other

major freely convertible currencies that form its core—leaving Moscow deeply

vulnerable.

In addition to the

world’s financial infrastructure, the companies that produce certain critical

goods—like semiconductors and other advanced technologies—are predominantly

located in G-7, European Union, and other economies that joined the U.S.

response. As a result, the coalition’s sanctions and restrictions hit the

Kremlin even harder. Russia now faces years or even decades of economic

decline. Foreign companies have exited the country en

masse, significantly degrading Russia’s economic base. Russia will see its

manufacturing sector shrink without access to these critical imports. One

outside analysis predicts that, in the long term, Russia’s economy could

contract as much as 30 to 50 percent relative to its prewar level. Most

importantly, these actions will degrade Russia’s military-industrial complex

and erode its ability to project power.

The lesson of these

actions is that their potency rests not on the size of the U.S. financial

system or the widespread use of the dollar alone but on the reach and resilience

of the international economic system. Far from undermining that system, this

global and coordinated response has underscored its power, value, and

importance.

Study To Practice

Over the past 80

years, U.S. sanctions policy has dramatically evolved. In 1940, when Adolf

Hitler’s Germany invaded Denmark and Norway, the U.S. Treasury Department froze

the latter two countries’ U.S.-held assets. Over the following year, it also

froze the help of other countries that Germany invaded. But unlike today’s

sanctions, these actions were designed only to keep those assets from falling

into the hands of the Nazi regime. Until the United States formally entered the

war, the Department of the Treasury did not prohibit trade or financial

transactions with Germany more broadly.

Over the twentieth

century, the United States increasingly employed economic sanctions as a core

foreign policy tool rather than merely as a supportive measure. For example, it

imposed various sanctions and export controls on the Soviet Union and countries

within the Soviet sphere beginning in the 1940s. It sanctioned South Africa in

the 1980s for its apartheid policies. Washington further modernized its

sanctions policies after the attacks of September 11, 2001. In 2004, the

government created the Treasury Department’s Office of Terrorism and Financial

Intelligence to coordinate Treasury’s sanctions and intelligence activities,

which further enabled it to use sophisticated sanctions strategies to target

terrorists and other non-state adversaries—as well as the countries harboring

them.

It isn’t just the

terrorist attacks that have demanded changes to U.S. sanctions policies. Over

the last two decades, the international financial system’s size and importance

have grown, requiring a more sophisticated sanctions apparatus. From 2001 to

2021, global external assets as a share of GDP nearly doubled. And from 2011 to

2021, the share of people over 15 with an account at a bank or mobile money

service provider jumped from 50 percent to 76 percent. At the same time, the

expansion of cryptocurrency and decentralized finance has created new ways to

hold and transfer value outside of traditional systems, enabling alternative

methods for states, people, and organizations to launder illicit revenues. This

evolution has created new ways to attempt to move beyond the reach of

sanctions, raising the stakes for governments using these economic measures to

hold rogue actors accountable.

Freight trains in Kaliningrad, Russia, June 2022

, in the spring of

2021, Yellen asked me to work with our colleagues at Treasury and the State

Department to conduct a comprehensive review of how U.S. sanctions authorities,

strategies, and implementation have evolved—the first study of its kind since

the attacks of September 11, 2001. In October of last year, we published the

results of this study: the 2021 Treasury

Sanctions Review. Its

many essential findings showed that sanctions are most effective when

coordinated with allies and partners, both because coordination bolsters

diplomacy and because multilateral sanctions are harder to evade. It concluded

that sanctions should be tied to a clearly articulated foreign policy strategy

that is, in turn, linked to discrete objectives. And the review determined that

U.S. sanctions should incorporate a detailed economic analysis of their

anticipated impacts, including the collateral effects.

Today, these

conclusions may sound obvious. But past sanctions were only sometimes well

calibrated. In total, the number of U.S. sanctions designations grew over 900

percent from 2000 to 2021—some more carefully designed than others—as the

number of U.S. sanctions programs increased more than 2.5 times. Our review

found that a more granular analysis would allow sanctions officials to target

restrictions better and achieve more nuanced objectives while minimizing

unintended effects.

Less than a month

after the review's conclusion, U.S. intelligence revealed that Russia was

beginning to plan for a potential invasion of Ukraine. It was fortuitous that

we had completed our work. In statements public and private, Biden made clear

that, should the invasion come to fruition, sanctions would be central to the

U.S. response. To ensure we were prepared, he tasked Secretary Yellen with

developing a sanctions strategy that would maximize the costs imposed on

Russia’s economy while minimizing the impact felt by the United States, our

allies and partners, and the global economy more broadly.

Responding To Russia

On February 24, 2022,

Russia began its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. From the beginning, it was

clear that crafting a response that was both effective and properly calibrated

would be challenging. Although the scale of the Kremlin’s brutality demanded a

powerful answer, the size and international integration of the Russian economy

made it hard to impose significant costs, especially without causing widespread

damage to the global economy. Russia is one of the world’s most populous states

and has a central role in global energy markets. To damage the Russian war

effort using economic tools, the United States needed to incorporate the

lessons from the sanctions review—and it had to do so quickly.

That started with the

lesson that sanctions should be tied to a clearly articulated foreign policy

strategy and linked to discrete objectives. In this case, the aim was to

degrade Russian President Vladimir Putin’s ability to wage his illegal war. To

that end, the United States has used a set of innovative and sweeping sanctions

and export controls to deny Russia the revenue and resources needed to pursue

its invasion and project power, including by diminishing its

military-industrial complex. The United States and its allies have also

undertaken substantial diplomatic engagement and provided abundant military and

economic support to Ukraine, totaling tens of billions of dollars. The Biden

administration has requested an additional $38 billion from Congress to assist

further. These goals reflect that sanctions alone are unlikely to stop Putin’s

invasion entirely. But they can be made it far harder for Putin to continue his

war and have dramatically lowered his chances of battlefield success.

One way to think

about this strategy is as a set of targeted, surgical strikes on Russia’s

ability to wage war. It has allowed the United States to significantly impact

Russia—frustrating Moscow’s ability to pursue its invasion and prop up its

economy—while limiting the collateral impact on the global economy, especially

on U.S. allies and developing economies. We decided to target three elements of

Russia’s economy: its financial system, elites, and the military-industrial

complex. To target the financial system, we sanctioned Russia’s key financial

institutions, immobilized its central bank reserves, and cut off many of its

banks from the SWIFT messaging system in the days immediately following the

invasion. To hit the network of elites and oligarchs who support the Russian

government and act as its agents and instruments, we set up an international

taskforce—the Russian Elites, Proxies, and Oligarchs (REPO) Taskforce, with

representatives from eight countries and the European Commission—to identify

and seize their assets in jurisdictions around the world. This effort would

prevent Russian oligarchs from accessing resources they could use to prop up

Putin’s regime. And to target Russia’s military-industrial complex and critical

supply chains, we implemented export controls and other restrictions that would

deny Russia the imports needed to keep its war machine operational, forcing

Russia’s military to steadily turn to outdated and less reliable weapons.

To make this targeted

strategy work, the Department of the Treasury had to work closely with a global

coalition of allies and partners—consistent with the sanction review’s

conclusions. From the outset, Biden and Yellen made multilateralism the

foundation of our response to Russia, building on the administration’s

commitment to rebuilding U.S. alliances and restoring trust in the United

States’ global role. At Biden’s direction, we began building our coalition far

before the war, reaching out to many of the allies and partners we consulted

during the sanctions review. In November, the U.S. intelligence community

quickly shared the intelligence pointing to Russia’s potential invasion with

U.S. allies and partners in Europe and began laying the groundwork for the

response. Although not every decision was finalized by February 2022, the

United States, its allies, and partners had developed a thorough set of initial

actions.

The composition of

this coalition has been critical to its efficacy. From a financial perspective,

it includes the issuers of the world’s major freely convertible currencies.

These currencies form the connective tissue of the global banking and payments

system, enabling efficient and low-risk cross-border finance and trade.

Russia’s need to transact in these currencies explains why the financial

sanctions were so impactful and why, despite its best efforts, Russia could not

escape its reach. For example, as of 2019, 87 percent of Russia’s foreign

exchange transactions were denominated in dollars. The European Union,

meanwhile, is Russia’s largest trading partner, making the EU’s actions to isolate

Russia highly potent economically. And because this coalition includes Japan,

South Korea, and Taiwan—the world’s most important producers of key advanced

technologies, along with the United States—its export controls have

successfully cut Russia off from access to critical imports such as

semiconductors, badly degrading its military in the process. To the extent

there are risks involved in unilateral sanctions, the lesson of the U.S.

response to Russia is that acting alongside allies and partners in the G-7—and

across Europe and Asia—is the best way to mitigate them.

A New Playbook

Washington and its

allies and partners have been innovative in the execution of this strategy. To

deny Russia the financial resources to fund its invasion, the coalition

immobilized Russia’s sovereign wealth fund and central bank reserves. This move

was deeply impactful. Over the preceding eight years, Russia had built up $630

billion in sovereign wealth and major bank assets to protect its economy from

the impact of potential sanctions. The coalition’s actions made much of this

war chest inaccessible, blunting the effect of Russia’s preemptive

actions.

The coalition is also

pursuing a novel approach to limit Putin’s revenue from Russia’s oil exports

without taking that oil off the market: the price cap policy implemented by the

European Union, G-7, and Australia earlier this month. The price cap was

designed to overcome a seeming dilemma. Since the beginning of the conflict,

the United States and its allies have purposefully crafted our sanctions to

allow Russian oil and gas exports to reach the global market, even as the

United States and some other governments have banned the import of these goods

into their own countries. This was done for good reason. With consumers and

businesses in the United States and around the world already under pressure

because of elevated energy prices—caused in substantial part by the Kremlin’s

actions—these governments did not want to add on. But it has meant that Russia

has continued to reap significant profits from its energy exports, especially

oil. At one point, Russia received more than $100 per barrel. Over the summer,

it received prices 60 percent more per barrel than it did the previous year,

meaning that Russia made more money despite the decline in its export

volumes.

Using traditional

sanctions strategies, the tension between these two objectives—restricting

Russia’s revenue while continuing to allow its oil to reach the market—would be

intractable. But the price cap policy balances these goals through a new

approach: pairing sanctions that cut off seaborne Russian oil shipments from

critical services such as insurance, trade finance, and shipping with an

exception for oil sold at or below a specific price. Rather than an outright

ban, the price cap essentially creates two markets for Russian oil: one

market—at or below a certain price—in which Russia’s oil exports keep flowing,

with the benefit of these services, and another market—above that price—where

Russian oil can only be shipped using services from alternative suppliers that

are likely to be more expensive and less reliable. It institutionalizes the

discount on Russian oil by setting a ceiling for buyers who formally join the coalition

imposing it and giving greater leverage to buyers outside the coalition to

negotiate lower prices—even if they do not officially adopt the policy. All net

oil-importing countries and consumers of oil globally stand to benefit from

lower oil prices;. At the same time, the Kremlin takes in less revenue as an

added benefit, low- and middle-income countries that need this cheaper oil are

likely to be the primary economic beneficiaries of the price cap.

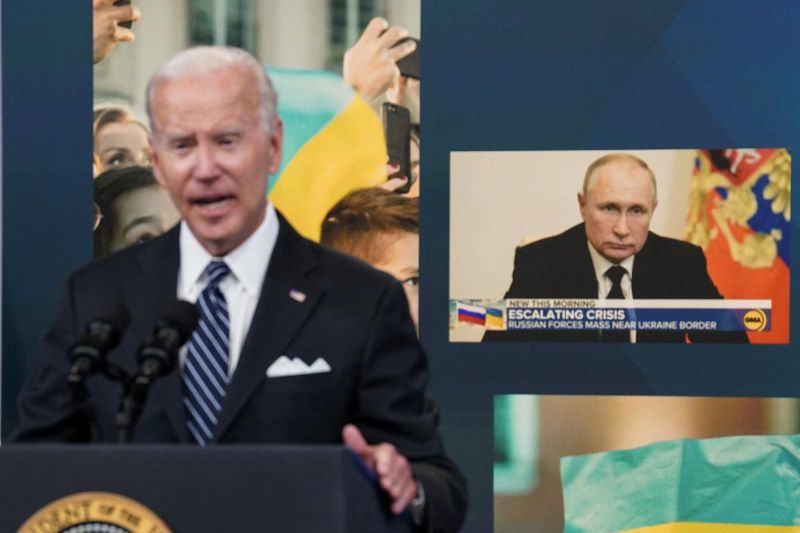

Biden speaking about gas prices in Washington, D.C.,

June 2022

In addition to its

creativity, the price cap policy is also emblematic of U.S. efforts to infuse rigorous

economic analysis into our sanctions, the review’s third key finding. In

addition to our traditional work with the Department of State, a team of

sanctions experts, economists, and financial market experts at the Treasury

Department—in coordination with the Department of Energy—has worked closely

with economic analysts in finance ministries and other departments at the

European Commission and across the G-7 to refine estimates of the price effects

of the seaborne service's ban; calibrate the right price for the cap itself

based on historical pricing patterns; and assess Russia’s potential response

based on the country’s oil output, equipment, and other variables. This new way

of deploying sanctions—to segment the market for Russian oil rather than ban it

entirely—has required corresponding innovation in analytic methods. Building on

this experience, the Treasury Department is currently recruiting a Chief

Sanctions Economist who will help develop a full-fledged unit and connected

analytical capabilities to enhance the United States’ ability to undertake this

detailed economic analysis in other instances.

Disrupting the

critical supply chains that feed Russia’s military-industrial complex has also

constituted a sea change for sanctions policy. The United States has focused

heavily on ending Russia’s war and its brutalities in Ukraine. The goal, put,

is to frustrate Russia’s ability to use the money they have to build the

weapons they want. But instead of concentrating on inflicting sheer economic

pain, the Treasury Department—in coordination with the Department of Defense

and Department of Commerce—and the United States’ allies have used sanctions

and export controls to go after the specific technologies and inputs Russia

needs to fight its war. This includes semiconductors, transistors, and software

that are only made outside Russia and, in many cases, only by the United States

and its allies. The U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence

estimates that measures by Washington and its partners have degraded Russia’s

ability to replace more than 6,000 pieces of military equipment, forced key

defense-industrial facilities to halt production, and caused shortages of

critical components for tanks, aircraft, and submarines. The world is seeing

the results of these shortages on the battlefield, where Ukraine’s tenacious

fighters have forced Russia to quickly exhaust its supplies of modern weapons

and turn to outdated, Soviet-era equipment or lower-quality alternatives

procured from North Korea and Iran.

Together, these

approaches constitute a bespoke strategy to deny Russia access to the revenue

it needs to pay for its war, cut Russia off from resources to prop up its

failing economy, and degrade its military capabilities. The design and

implementation of these actions have required technical expertise and elaborate

diplomatic coordination. The countries behind them will have to continue

working together to prevent Russia from evading the various restrictions. But

these economic measures are already eroding Russia’s ability to project power

and will shape international economic policy for decades.

The Path Forward

When we began our

campaign to hold Russia accountable, using all of our economic and financial

tools, we were met with criticism from some that our actions risked unraveling

the global financial system. Ten months into this conflict, we can safely

conclude the opposite. Far from driving a wedge between the United States and

its allies, these sanctions have offered the strongest possible statement of

our unity in the face of Russia’s aggression. They have demonstrated that

Washington and its partners are willing to defend the principles at the core of

the international economic system—including self-determination, territorial

sovereignty, and free and open monetary exchange—even when it may cost their

economies, representing a literal investment in the future of the international

economic order.

The coalition’s

response to Russia’s invasion reflects both the conclusions of our sanctions

review and particular elements of the international economic system’s

design—from the dollar’s role to the correspondent banking networks that

facilitate payments within it to the geography of the service providers that

support accurate economic exchange between its participants—that enable the

benefits the system provides. These features also make denial of the system’s

benefits so potent. The multilateral coordination that has undergirded the

coalition’s actions from beginning to end—from strategy to tactics and

execution—has reinforced that same system in the face of its greatest threat in

a generation.

None of this means

that the international economic system does not need updating. The system will

require new investment as it adapts to the twenty-first century. The United

States and its allies should modernize the international institutions that form

the backbone of this system, such as the multilateral development banks;

finalize the international agreement on a global minimum tax that more than 135

countries reached at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

last fall; and update the international payments infrastructure to make it

faster, cheaper, and more inclusive. These actions will help ensure the

international economic system continues to drive global prosperity, that it

lives up to the values embedded in its creation, and that it remains robust

enough to matter when malign actors are denied access.

Of course, there is

more work to be done. But there is no doubt that what the United States and its

allies have accomplished is historic—and heartening. This coalition is not only

holding Russia accountable for its unconscionable war; it is doing so in a

multilateral fashion that demonstrates the enduring strength and importance of

investing in the international economic system. We will remain focused on

holding Russia accountable as the country wages its brutal war and will keep

supporting Ukraine for as long as it takes. Years or decades from now, Russia’s

invasion and the resulting collective response will be viewed as a moment in

which the international economic system cemented its essential role when faced

with an enormous challenge.

For updates click hompage here