By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

On July 30, Masoud

Pezeshkian was sworn in as Iran’s new president. Mere hours after the ceremony,

Ismail Haniyeh, the former prime minister of the Palestinian National Authority

and chairman of the Hamas political bureau, was assassinated by Israel in a

guesthouse near the presidential complex. Haniyeh had been invited to attend

the inauguration, and his killing on Iranian soil cast a shadow over the

proceedings. It also previewed the challenges Pezeshkian will face in pursuing

his foreign policy ambitions.

But Pezeshkian is

well prepared to handle all the difficulties that will arise over the coming

years. Pezeshkian recognizes that the world is transitioning into a post-polar

era where global actors can simultaneously cooperate and compete across

different areas. He has adopted a flexible foreign policy, prioritizing

diplomatic engagement and constructive dialogue rather than relying on outdated

paradigms. His vision for Iran's security is holistic, encompassing both

traditional defense capabilities and the enhancement of human security through

improvements in the economic, social, and environmental sectors.

Pezeshkian wants

stability and economic development in the Middle East. He wants to collaborate

with neighboring Arab countries and to strengthen relations with Iran’s allies.

But he also wants to engage constructively with the West. His government is ready

to manage tensions with the United States, which has also just elected a new

president. Pezeshkian hopes for equal-footed negotiations regarding the nuclear

deal, and potentially more.

Yet as Pezeshkian has

made clear, Iran will not capitulate to unreasonable demands. The country will

always stand up to Israeli aggression. And it will be undeterred from

protecting its national interests.

Khatami himself has also publicly endorsed Pezeshkian,

along with reformist parties that previously supported Rouhani in his

successful 2013 presidential bid. These endorsements underscore the

significance of Pezeshkian’s candidacy within the reformist movement, which is

aiming to revive its influence.

Just a few months

after the signing of the 2015 nuclear deal, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of

Action (JCPOA), reformists achieved a historic victory in the February 2016

parliamentary elections, securing all 30 seats in Tehran. Rouhani then won the 2017

presidential election with more than 57 percent of the vote.

Although the Iranian

Constitution designates the president, elected by direct popular vote, as the

head of the government, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has significantly

expanded his influence over the past few decades. This has been achieved through

the creation of parallel institutions, the extension of their powers, and the

formulation of overarching policies for the regime. The supreme leader’s

influence is further reinforced by his private veto power over members of the

president’s cabinet—increasing his control and

limiting the president’s authority.

Yet Iranian society

has undergone substantial changes over the past decade, leading many to doubt

whether reformists can bring about any meaningful changes in Iran’s governance.

Since the nuclear

deal was signed a moment seen as the pinnacle of reformist and moderate

popularity in Iran, the political landscape has shifted dramatically. Moderates

have since become marginalized within Iranian society. After Ebrahim Raisi’s victory

in the 2021 presidential election, reformists were completely removed from the

government. However, even before this month’s election, the Guardian Council

had disqualified the main figures of the reformist movement from running,

leaving only Pezeshkian.

The U.S.

withdrawal from the JCPOA,

Khamenei’s opposition to improving Tehran-Washington relations during the Obama

administration, and military actions conducted by the Islamic Revolutionary

Guard Corps (IRGC)—including, most recently, the launching of missiles and

drones at Israel in April—all marginalized moderates. Additionally,

Iran’s arrest of U.S. sailors and seizure of patrol boats in

the Persian Gulf, the expansion of the IRGC’s Quds Force activities in Syria,

and Iran’s broader support of the so-called Axis of Resistance have escalated

tensions with the West.

These military

actions impeded the Rouhani government from fully capitalizing on the benefits

of the nuclear deal, thereby limiting the potential advantages that it could

have brought to the reformist and moderate political movement. The IRGC’s

actions have also deterred foreign investors who might otherwise have been

eager to engage in business with Iran.

Moreover, during

Rouhani’s tenure, Iran witnessed several rounds of nationwide protests,

reflecting widespread societal dissatisfaction with the government’s

performance. They began with the protests in 2017 and 2018 against economic

problems, where the slogan “Reformist, principlist,

it’s over” from protesters

targeting the Rouhani government was first heard. (Conservatives are known as “principlists” in Iran.) Over time, these slogans began to

target Khamenei as well. In 2019, protests erupted in response to high gasoline

prices, initially directed at the Rouhani government but soon expanding to

criticize the entire regime.

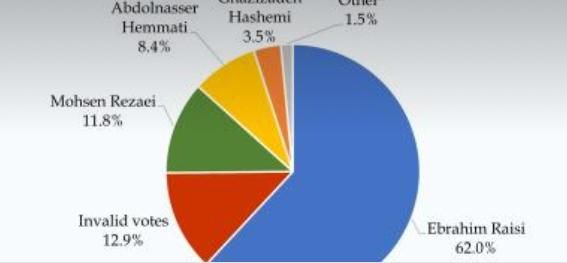

These developments

led to the lowest voter

turnout in the Islamic

Republic’s history in the 2021 presidential election, with only about 48

percent voter participation and Raisi winning 62 percent of the vote. (Raisi

died in a helicopter crash last month, paving the way for Friday’s election.)

Politics is Local

This is a historic moment

for stability that the world should not let slip. Tehran certainly won’t. After

over two centuries of vulnerability, Iran—under the leadership of Supreme

Leader Ali Khamenei, has finally proven that it can defend itself against any

external aggression. To take that achievement to the next level, Iran, under

its new administration, plans to improve relations with neighboring states to

help create a regional order that promotes stability, wealth, and security. Our

region has been plagued for far too long by foreign interference, wars,

sectarian conflicts, terrorism, drug trafficking, water scarcity, refugee crises, and environmental degradation. To tackle these

challenges, we will work to pursue economic integration, energy security,

freedom of navigation, environmental protection, and interfaith dialogue.

Eventually, these

efforts could lead to a new regional arrangement that reduces the Persian

Gulf's reliance on external powers and encourages stakeholders to address

conflicts through dispute resolution mechanisms. To do so, the region’s

countries may pursue treaties, create institutions, enact policies, and pass

legislative measures. Iran and its neighbors can start by mimicking the

Helsinki process, which led to the formation of the Organization for Security

and Cooperation in Europe. They can use the never-implemented mandate that the

United Nations Security Council gave to the UN secretary-general in 1987, under

Resolution 598. That resolution, which ended the Iran-Iraq War, called on the

secretary-general to consult with Iran, Iraq, and other regional states to

explore measures that could enhance security and stability in the Persian Gulf.

The Pezeshkian administration believes this provision can serve as the legal

basis for comprehensive regional talks.

Of course, there are

obstacles that Iran and its neighbors must overcome to foster a peaceful,

integrated regional order. Some differences with its neighbors have deep-rooted

origins, shaped by varying interpretations of history. Others arise from misconceptions,

mainly rooted in poor or insufficient communication. Still others are political

constructs implanted by external forces, such as allegations concerning the

nature and objective of Iran’s nuclear program.

But the Persian Gulf

must move on. Iran’s vision aligns with the interests of Arab countries, all of

which also want a more stable and prosperous region for the sake of future

generations. Iran and the Arab world should thus be able to work through their

differences. Iran’s support for Palestinian resistance could help kick-start

such cooperation. The Arab world, after all, is united with Iran in its support

for restoring the rights of the Palestinian people.

Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian speaking in Basra,

Iraq, September 2024

Hitting Reset

After more than 20

years of economic restrictions, the United States and its Western allies should

recognize that Iran does not respond to pressure. Their intensifying coercive

measures have consistently backfired. At the height of Washington’s most recent

maximum-pressure campaign—and just days after Israel assassinated Iran’s

leading nuclear scientist, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, Iran’s parliament passed a law

directing the government to rapidly advance its nuclear program and reduce

international monitoring. The number of centrifuges in Iran has increased

dramatically since 2018—when U.S. President Donald Trump withdrew from the

nuclear deal—and enrichment levels have skyrocketed from 3.5 percent to over 60

percent. It is hard to imagine any of this would have happened if the West had

not abandoned its cooperative approach. In this regard, Trump, who will take

office again in January, and Washington’s partners in Europe have themselves to

blame for Iran’s continued nuclear progress.

Instead of increasing

pressure on Iran, the West should pursue positive-sum solutions. The nuclear

deal provides a unique example, and the West should look to revive it. But to

do so, it must take concrete and practical actions—including political, legislative,

and mutually beneficial investment measures—to make sure Iran can benefit

economically from the agreement, as was promised. Should Trump decide to take

such steps, then Iran is willing to have a dialogue which would benefit both

Tehran and Washington.

On a broader scale,

Western policymakers must acknowledge that strategies aimed at pitting Iran and

Arab countries against one another by supporting initiatives such as the

so-called Abraham Accords (which normalized ties between various Arab countries

and Israel) have proven ineffective in the past and will not succeed in the

future. The West needs a more constructive approach—one that takes advantage of

Iran’s hard-earned confidence accepts Iran as an integral part of regional stability, and seeks collaborative solutions to shared

challenges. Such shared challenges could even prompt Tehran and Washington to

engage in conflict management rather than exponential escalation. All

countries, Iran and the United States included, have a mutual interest in addressing

the underlying causes of regional unrest.

That means all

countries have an interest in stopping the Israeli occupation. They should

realize that the fighting and fury will continue until the occupation ends.

Israel may think it can permanently triumph over the Palestinians, but it

cannot; a people who have nothing to lose cannot be defeated. Organizations

such as Hezbollah and Hamas are grassroots liberation movements that have

emerged in response to occupation and will continue to play a significant role as long as the underlying conditions persist—which is to say

until the Palestinians' right to self-determination is realized. There can be

intermediate steps, including immediate cease-fires in Lebanon and Gaza.

Iran can continue to

play a constructive role in ending the current humanitarian nightmare in Gaza

and work with the international community to pursue a lasting and democratic

solution to the conflict. Iran will agree to any solution acceptable to Palestinians,

but our government believes that the best way out of this century-long ordeal

would be a referendum in which everyone living between the Jordan River and the

Mediterranean Sea—Muslims, Christians, and Jews—and Palestinians driven to

diaspora in the twentieth century (along with their descendants) would be able

to determine a viable future system of governance. This is in line with

international law and would build on the success of South Africa, where an

apartheid system was transformed into a viable democratic state.

Constructive

engagement with Iran, coupled with a commitment to multilateral diplomacy, can

help build a framework for global security and stability in the Persian Gulf.

It can thereby reduce tensions and foster long-term prosperity and development.

This shift is crucial for overcoming entrenched conflicts. Although today’s

Iran is confident that it can fight to defend itself, it wants peace, and it is

determined to build a better future. Iran can be an able and willing partner,

so long as its partnerships are based on mutual respect and equal footing. Let

us not miss this opportunity for a new beginning.

For updates click hompage here