By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Israel and its Current Problems Part Two

Last April, it

appeared as though escalation between Israel and Iran could plunge the entire Middle East into conflict.

Israel’s strikes on the Iranian consulate in Damascus prompted Iran to

retaliate by launching a barrage of missiles and rockets into Israel—the first

time that Iran had openly attacked the country. But after Israel responded in a

relatively muted way, both countries moved on from the confrontation.

Observers, too, put aside their most acute worries, comforted by the fact that

both countries had shown that they had no interest in a wider war.

This conclusion,

however, was premature. In September, Israel intensified its campaign against

Hezbollah, the Iranian-backed paramilitary group operating in Lebanon. This

marked an important shift: it suggests that Israeli leaders decided they wanted

to actively reshape the balance of power in the Middle East. Much more than its

actions in Gaza, Israel’s war against Hezbollah threatens Iran’s ability to

project power and profoundly diminishes its ability to deter Israeli

interventions into its own domestic politics and nuclear program. The weakening

of Iran’s position will benefit Israelis in the short term. But in the long

term, it will significantly increase the risk of a regional war and even the

likelihood that Iran will acquire nuclear weapons. To avoid being dragged into

yet more conflict in the Middle East, the United States must work to restrain

further Israeli action and stabilize the balance of power.

Israel in Context

For many generations,

Jewish communities in the Russian Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian

Commonwealth enjoyed a large degree of administrative and cultural autonomy,

whether through the Council of Four Lands in Poland or the elected local kahal

Jewish community committees in tsarist Russia. In many senses, Jewish autonomy

under autocracies formed the basis of Simon Dubnow’s later

thinking about Jewish autonomism, the cause of Jewish autonomy in the Diaspora,

including within a future democratic, multicultural Russia.

Between 1580 and

1764, the Council of Four Lands was principally in charge of collecting taxes

from the Jews on behalf of the royal treasury. Sometimes regarded as the heir

to the Sanhedrin of antiquity, the council functioned in what is known as

Greater Poland, Little Poland, Galicia (with Podolia), and Volhynia,

and its members were acknowledged as the leaders of Polish Jewry in secular

affairs.

The council met twice

a year to discuss and arrange interactions with the authorities on both

religious and secular matters. For the first hundred years of its existence,

leading rabbis were the dominant force, but in time, the difference between the

secular council and the rabbinical leadership became more and more pronounced.

In 1688, the council forbade rabbis from interfering in matters of taxation.

Five decades later, in 1739, it reiterated this demand and insisted that the

rabbis confine themselves to matters of religion.1

The shift in the

council’s leadership away from the rabbis and toward lay leaders were

influenced by the budding Enlightenment movement in western Europe and the

growing desire of Polish Jews to strengthen their oversight of their communal

representatives.

The Jews of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth would experience a profound

change in the coming decades after the tsarist empire annexed the Polish

provinces and introduced a new policy of coercive governance, combined with

limited integration for the minorities under its rule. In 1791, imperial

authorities created the institution of the kahal as a decentralized successor

to the council. Kahal committees were formed in the roughly 1,000 separate

Jewish communities in the Pale of Settlement. Each committee numbered five to

nine members and functioned as an administrative and enforcement body under the

auspices of the imperial regime, and executed its

will. It soon became the central element in Jewish life. According to historian

Benjamin Pinkus, even before the kahal system, Jewish autonomy “was fuller than

that conceded to other national and religious minorities within Belorussia.”2 The

kahal was governed according to Jewish law and was responsible for collecting

taxes from Jews, representing and policing members of the community, and

issuing identity documents.

During the reign of

Alexander I, some called for the integration of the Jews as “good and useful

citizens.” But this budding liberalism and the opening it offered for

Western-style enlightenment lacked the administrative foundation for any

meaningful reform. The tsarist regime preferred a policy of segregation based

on the kahal structure as an effective means of control. At times, Tsar

Alexander I tried to form a Jewish advisory body and even tried to help to

combat blood libels.

Under the tyrannical rule

of his successor, Nicholas I, this dialogue-oriented attitude gave way to a

harsh dynamic of arbitrary coercion. In 1827, Nicholas abolished the practice

of purchasing exemptions from military service and ordered Jewish community

leaders to supply conscripts as a collective responsibility; with this, the

kahal system’s moral authority quickly waned in the eyes of many Jews, as did

solidarity and confidence in their own representatives, whom they now perceived

as lackeys of the tsarist regime. Jews accused these community leaders of

corruptly exploiting their power to decide who was, and who was not, doomed to

conscription. Any contacts with the authorities that were perceived as

excessively close evoked suspicion and any cooperation with the government’s

proposed reforms were feared as the prelude to forced Christianization.

Nonetheless, the kahal system remained the only structure that enabled the Jews

to enjoy a high level of communal cohesion under their own elected leadership.3

In 1844, the Russian

government changed its policy toward the Jews overnight. Their autonomy was

deemed too broad and threatening, and Tsar Nicholas abolished the kahal system.

A year later, it was decreed that within five years, the wearing of traditional

Jewish garb would be totally forbidden. According to Benjamin Pinkus, the abolition of the kahal system meant that elected

Jewish leaders were stripped of their powers, and “synagogue authorities were

forbidden to exercise any pressure, except reprimand and warning.”4

Even without the

kahal committees, “Jewish communities continued to deliver taxes and

conscripts, as the state required of them.”5 Over time, however, their internal

leadership lost their status and powers. Rebellious youngsters and

intellectuals, as well as entrepreneurs and rich merchants, challenged the old

guard and its traditional system of control. The community was divided over the

key question that keeps recurring: Who speaks for the Jews, and on what

authority?

The tsarist regime’s

erratic flip-flopping between wanting to rule the Jews as a collective and

fearing that their cohesion would constitute a threat reflected its growing

apprehension about national minorities in general. The Poles, Ukrainians,

Byelorussians, and Caucasian peoples all awaited the opportunity to assert

their independence. Tsar Nicholas’s ferocity and frequent, unanticipated policy

swings compelled the Jews to reconsider their future. Increasingly concerned

that he would take devastating steps against them, they came up with innovative

initiatives to ensure the continued existence of their collective life outside

(or after) an imperial Russia.

However, most

residents of the Pale of Settlement were unaffected by the romantic ideas of

the Enlightenment in Germany and could conceive of no solutions beyond their

traditional way of life. Hasidic Judaism remained the dominant force among

Russian Jewry until the second half of the nineteenth century. Under the rule

of Alexander II, more and more educated Jews began trying to fit into the

empire along the lines of the western European model, as fully equal citizens.

The residence rights

accorded to these “Makov Circular Jews” always

rested on a shaky legal foundation, and the Ministry of Internal Affairs

withdrew the circular in 1893.

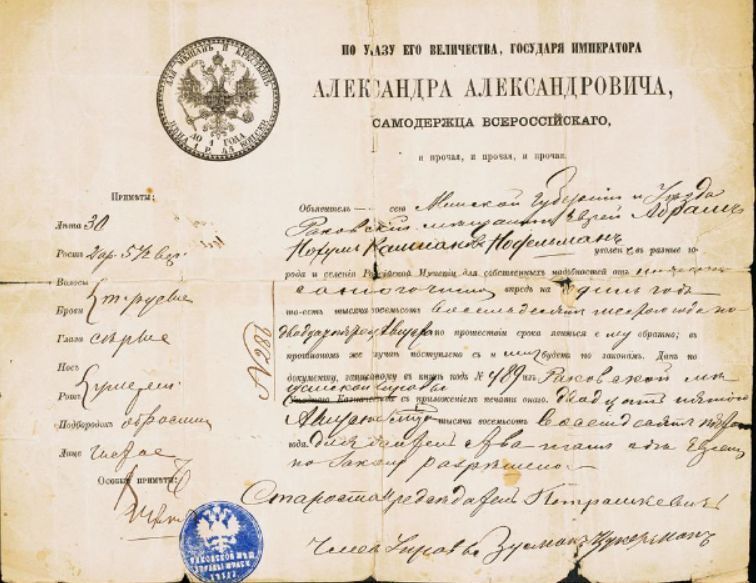

Image of a temporary permit to travel for business

outside the Pale of Settlement:

The reforms during

his reign, the upheavals in western Europe, and the revolutions of 1848 laid

the foundation for the emergence of anti-establishment Jewish nationalist

movements. They fed upon the socialist and liberal revolutionary trends in the

West while also drawing inspiration from the Bible and ancient Jewish

sovereignty. After Russia’s defeat in the Crimean War, Alexander II became

increasingly dependent on the taxes paid and services rendered by affluent and

educated Jews. They became indispensable to the rehabilitation of Russia’s

infrastructure, and since the regime was so dependent on private capital, a

small cadre of merchants became significant financial players for the Russian

government.

The new Jewish elites

also became the principal mediators between the imperial regime and their own

communities. In the 1870s, wealthy Jews, notably the Günzburg family,

were known for their philanthropy and efforts to sway the government on Jewish

affairs. They succeeded in getting some of the restrictions on settlement

abolished, as well as expanding the Jews’ freedom of occupation outside the

Pale. Their role was similar to that of the court Jews

of central Europe after the Thirty Years’ War, and they secured an elevated

legal status for themselves.6 These developments and Tsar Alexander’s reforms

spurred an internal debate about the opportunities and dangers inherent in

Russification versus the preservation of a distinct Jewish existence. Some of

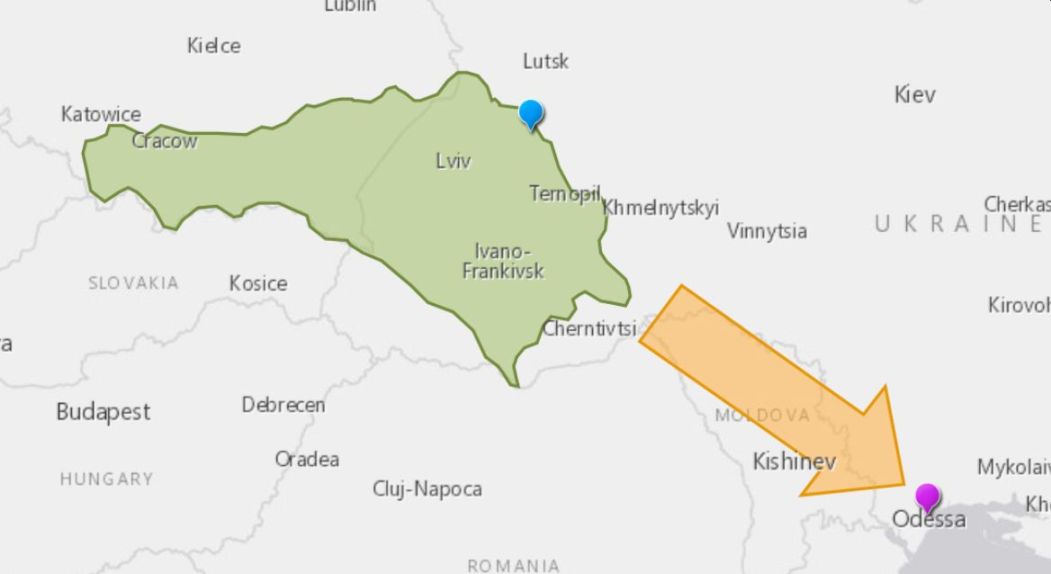

the wealthy and educated Jews in cities such as Odessa and St. Petersburg were

active in reshaping community life with an emphasis on liberal Jewish-Russian

integration.

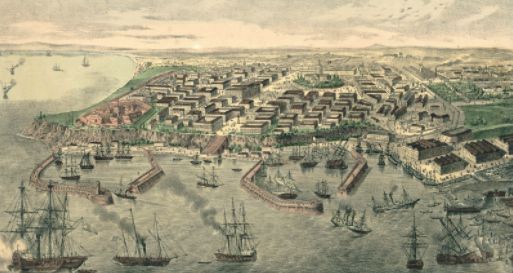

The story of Odessa is a fascinating example

of Jewish flourishing in eastern Europe. In 1790, according to an unofficial

census, there were a few hundred Jews living in the city, mostly petty traders.

By 1860, their ranks had swelled to 17,000, about one-quarter of the city’s

population. By the turn of the century, Odessa was spoken of as a “Jewish city”

and the Jews had become its economic engine, and in the early twentieth

century, two-thirds of the craftsmen and industrialists in Odessa were Jews.

Odessa, in the words of historian Charles King, “was New Russia’s answer to the

shtetl,” a place where Jews were not isolated. Instead, they fit into society,

were nourished by the prevailing enlightenment, and were optimistic that they

could convince the Russian authorities of their value.

Imperial authorities

cooperated with the modernizers by banning the wearing of the kapotah, the knee-length jacket donned by Orthodox Jewish

men, who were now battling for the survival of their traditional way of life.

They sometimes used underhanded methods to do this, such as leveling false

accusations of subversion against poet Judah Leib Gordon, one of

their harshest critics. They reported him and his wife to the Russian

authorities, who banished them on the pretext of anti-tsarist subversion.

Hasidic Jews saw

Odessa as a den of Jewish thieves and heretics. In Fishke the Lame

(The Book of Beggars), by S. Y. Abramovitsch,

the father of Yiddish literature known by his pen name Mendele

Mocher Sforim, the main character, Fishkeh, sums it up by saying: “Your Odessa is not for me.”7

Among the Jewish intellectuals

in Russia were early Zionists who preached progress but condemned the Western

tendencies toward assimilation. They produced flourishing Hebrew literature

that drew upon biblical sources and extolled the glory of the Jewish

sovereignty of ancient times. Avraham Mapu (1808–1867) became one of

the most important heralds of modern Hebrew literature, arousing the national

consciousness of young Jews with his 1853 book Love of Zion, the first modern

Hebrew novel

Mapu blazed a

path for the celebrated writer Peretz Smolenskin (1842–1885),

who called for the revival of Hebrew nationalism and denounced Jewish

integration in Russia as a shameful surrender on the part of an ancient

nation. Smolenskin, influenced by the Polish

national uprising in 1863, condemned both the rabbinic establishment and the

forces of assimilation. Having grown up in a small village in Byelorussia and

having been a fervent rebel against the yeshiva world he was raised in, Smolenskin was also the harshest and most prominent

critic of Reform Judaism and the Enlightenment ideas of Moses Mendelssohn,

which he was exposed to after moving to Odessa. He continued his relentless

struggle against them from Vienna, where he founded the Hebrew monthly Hashachar (“The Dawn”), devoted to the revival of the

Hebrew language, in 1869.

In advocating Hebrew

nationalism as a substitute for assimilation, Smolenskin was

advancing a similar ideology to Moses Hess, but his was based on and couched in

the Hebrew language. Like Hess, and unlike other Russian Jewish intellectuals

who admired what modernity and enlightenment had achieved for their brethren in

the West, Smolenskin condemned the Reform

model for making Judaism an empty, lifeless, universal religion. He despised it

for erasing the yearning for Zion from the liturgy, for abandoning Hebrew and

replacing it with German, and for giving up the solidarity of the People of

Israel and their symbiosis of nation and religion. He argued that religion and

nationalism went hand-in-hand in Judaism, and the

Hebrew language was the essential foundation of both. Those who renounced the

use of Hebrew in their prayers were betraying their people and their religion;

to his mind, without the Hebrew language, there was no Torah, and without the

Torah, there was no Jewish nation.8

On the spectrum

between Orthodoxy, which wanted to remain aloof from the rest of the Russian

Empire, and the forces of innovation and modernity, which sought integration

and progress within the empire, there were also the voices of some educated

rabbis who, decades before Pinsker and Herzl, emphasized that a

commitment to Jewish nationhood was no less important than a commitment to

religion, and perhaps even took precedence. They believed the preservation of

the Jews’ tribal nature mandated them to maintain strong ties to their

historical homeland and Hebrew as an everyday language, not only as a sacred

tongue. These pre-Zionist rabbis spoke in messianic terms of the “Restoration

of Israel.” They were inspired by rabbis from outside the Russian Empire, most

prominently Nachman Krochmal, Zvi Hirsch Kalischer,

and Judah Alkalai, all of whom were early harbingers

of Religious Zionism in the Land of Israel. The ability of Orthodox rabbis to

adopt these messianic and revolutionary calls for settlement in what was then a

neglected corner of the Ottoman Empire is a testament to the latent potential

within the Jewish religion to adapt itself to the world of modernity.

The succession of Alexander III

By 1880, Russian Jews

could still not integrate along with the western European model, but they did

enjoy a reasonable level of personal and public security, like other imperial

minorities, both in the Pale of Settlement and the cities. The tsarist regime

did not degenerate into mass murder, notwithstanding some violent, arbitrary

outbursts on the government’s watch, as well as substantial oppression and

discrimination. But the assassination of Alexander II in 1881 and the

succession of Alexander III led to an abrupt change in the lives of Russia’s

Jews.

In response to the

chaos caused by a series of such expulsions in 1880, the Minister of Internal

Affairs, Lev Makov, issued a ministerial

circular dated 3–15 April 1880, permitting Jews who had settled illegally

before that date to remain in place. The residence rights accorded to these “Makov Circular Jews” always rested on a shaky legal

foundation, and the Ministry of Internal Affairs withdrew the circular in 1893.

A major revision of

the Pale occurred in the wake of anti-Jewish pogroms of 1881–1882 and continued at

differing levels of intensity and capriciousness over the next two decades with

the backing of the regime. The tsars directly encouraged harsh legal measures

and indirectly approved “spontaneous” attacks on Jews. Every day brought fresh

peril, and their fear of this arbitrary violence disrupted their vision of

progress and integration under the Romanov monarchy. Even the flourishing

community of Odessa, about whom the Yiddish phrase “You can live like a king in Odessa” was coined, was

abruptly transformed from being a place of great hope for tolerant cosmopolitanism

into a place of anti-Semitic chaos. As the Golden Age in Spain, the promise and

calamity of Odessa were a repetition of what could happen to the Jews without

Jewish sovereignty.

This insecurity and

chaos gave a boost to Zionism and the forces of liberalism. It also

strengthened the spirit of the socialist revolution, although in the early

years of the twentieth century, up to the October Revolution, Jews “broadly

rejected socialism in any guise…as the solution to the problem of the Jews in

Russia.”9 Despite this, many who were motivated by the winds of secularization

and political instability wanted to be part of the overthrow of the

autocracy.10

In the end, however,

the irresistible allure of the American Dream and the drive to migrate westward

proved supreme. Between 1881 and 1914, two million Jews left the Russian Empire

for the United States, accounting for some 80 percent of their emigration from

eastern Europe. Some brought revolutionary, left-wing ideas to the US and

featured among the leaders of its socialist and communist movements. Only a

handful of Russian Jews went to Palestine, many of them influenced by the

Lovers of Zion (Hibat Zion) movement, which had become the exemplar and

catalyst of organized Zionism in Eastern Europe.

The American Jewish

community was transformed by this mass migration. With time, the United States

would become the most important Jewish community in the world. However, toward

the end of World War I, there were still more Jews in the teetering and soon-toppled

Russian Empire than anywhere else in the world because of tremendous natural

growth rates, despite the trauma of the pogroms. At the turn of the twentieth

century, the number of Jews in Russia was estimated at between five and seven

million.11

The Kishinev Pogrom

The constant fear of

pogroms and revolutionary ferment drove many Jews to political activism.

Disgusted at the passivity and fatalism of their parent's generation, young

Jews refused to accept further affronts to their dignity or to wait to be

slaughtered. They mobilized to fight the violence and depredations against

their people at all levels of society and the state. The Jews of imperial

Russia reached their breaking point with the infamous Kishinev pogrom of 1903.

Many Jews realized that

eastern Europe had become a deathtrap. But those who were so versed in

commemorating calamities were also adept at denying reality and snapping back

to old routines. A debate emerged: What should the future hold for the Jews of

the Russian Empire? They grappled with many different ideas, both before and

after the overthrow of the Romanovs in 1917, including Jewish sovereignty and

new ways of living in the Diaspora. At one end, Zionism called for the

“negation of the diaspora” and the creation of a Jewish state. On the other,

there were demands for full integration in the Diaspora based on civil,

economic, and political equality. Yet others called for Jewish autonomy in the

Diaspora.

Jews also debated two

models of cultural autonomy after the fall of the tsars; one model envisaged

the Jews as a minority like any other recognized national group in a

proletarian Russian state while the other saw them enjoying self-rule as part

of a federative arrangement in a liberal state in which national groups would

have cultural (but non-territorial) autonomy. The latter was the vision of

Simon Dubnow, who declared:

It is our duty to

fight against the demand that the Jews give up their national rights in

exchange for rights as citizens…. Such a theory of national suicide that

demands that the Jews make sacrifices for the sake of equal rights, the like of

which are not demanded of any other nationality or language group, contradicts

the very concept of equal rights and of the equal value of all men.12

One element cropped

up in every discussion of the Jewish future, the definition, status, and

location of the Jewish homeland. In the dispute between advocates of

sovereignty and those who favored a diaspora-based solution, the appearance of

the Hibat Zion movement gave a significant boost to the Zionist idea.

However, Zion argued that Jews would forever be foreigners in Russia, and the

way out of their distress was emigration to their historic homeland. Diasporists and proponents of autonomy emphasized the concept

of “hereness”, which meant that Jews belonged to the places where they lived,

just like any other nation.

Prominent among the

diaspora advocates was the Bund (Yiddish for “union”), a movement founded in

1897 as a “General Union of Jewish Workers” in Russia, Poland, and

later, Lithuania. It was the first social-democratic organization in the

Russian Empire and became a mass movement. As such, it was the most modern and

popular diasporic model in eastern Europe and a key component in the formation

of the socialist movement in Russia and the pan-European left.

There were two

contradictory streams within the Bund, one universalist and the other

specifically Jewish. The first advocated unity with all socialist movements,

Jewish and non-Jewish, for the sake of the proletarian class struggle; the

second called for joining with other Jewish movements to preserve and bolster

Jewish particularity and national solidarity. The Bund’s attempt to maintain an

independent Jewish entity within the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party

created internal contradictions and provoked clashes with both Jewish and

non-Jewish bodies. In Jewish circles, its universalism aroused opposition due

to the fear of assimilation and erosion of tradition.13 But among Russian

socialists, the majority, including Lenin in his early role as the socialists’

leader-in-exile, saw the Bund’s goal of becoming an independent ethnonational

party as a threat to the unity of the working class.

In 1903, Lenin

contended that the Jews had long ceased to be a nation, “for a nation without

territory is unthinkable.” He dismissed the notion of diaspora nations in

general and of a Jewish diaspora nation in particular, claiming: “The idea of a

Jewish nationality runs counter to the interests of the Jewish proletariat, for

it fosters among them, directly or indirectly, a spirit hostile to

assimilation, a spirit of the ‘ghetto.’”

Historian Zvi Gitelman writes that “for Lenin, there was no

Jewish nation, only a ‘Jewish Problem’,” and this problem would only be solved

if the Jews assimilated and abandoned their distinct cultural identity.14

The Bund never

succeeded in finding the right formula to ensure the survival of the Jewish

tribe in alliance with other socialists. At the same time, Jewish thinkers

proposed two other agendas that were not as politically influential as the

Bund’s but still had an impact. The more important of these was Jewish

autonomism, Simon Dubnow’s vision of Jewish

autonomy as a diaspora nation. The other was Yiddishism, socialist intellectual

Chaim Zhitlovsky’s idea for a “Yiddish

language community” to replace the Jews’ religion-based identity, which he

thought was going to disappear. Zhitlovsky’s form

of autonomy would first be established in the multicultural Russia that would

emerge from the embers of the revolution. He suggested that Yiddish would be

the language of instruction in schools and the working language of other

institutions. Yiddishists held a conference

in Bukovina in 1908 and declared Yiddish “a national language of the Jewish

people.”15

Zhitlovsky was something of a Zionist before taking a sharp

turn and backing the Bolsheviks. Realizing his mistake, he later fled to the

United States and promoted the idea of turning the Land of Israel into a

Yiddish, not Hebrew, national cultural center. He predicted that masses of Jews

would stream to a Yiddish-speaking national home.

Historian Zvi Gitelman sardonically said: “Whether Zhitlovsky seriously thought that Sephardic Jews would

adopt Yiddish, or whether he simply ignored their existence, is not clear, but

telling.”16 Zhitlovsky died in Canada,

together with his eccentric proposal.

Simon Dubnow showed some sympathy for Yiddishism but did not

see it as the heart of the national culture of eastern European Jewry. For him,

the Jews were multilingual people and speakers of Russian, Yiddish, and

Hebrew. Dubnow, a gifted historian, considered

himself a missionary for Jewish history. He made a great contribution to the

study of eastern European Jewry and called upon them to proudly brandish their

past as the key to ensuring their national future. He advocated the study of

history and the documentation of Jewish life as a modern alternative to Torah

study. He also earned the widespread recognition of

social scientists as the leading expert in the field of diaspora studies, a

branch of the study of nationhood.

Dubnow was

a member of the intellectual elite and emerged in the Byelorussian part of the

Pale of Settlement; he later moved to St. Petersburg, Odessa, Kaunas, Berlin,

and Riga. The Kishinev pogrom of 1903 shocked him deeply and led him to

cooperate with Ahad Ha’am and Hayim Nahman Bialik in

investigating the massacre. “Stunned by the thunder of Kishinev,” he later

wrote, “we each sat in our own homes in Odessa with broken hearts and seething

with impotent anger. When the horrendous news reached our town, so close to the

martyrs, the pen dropped from my hand and I could not

return to my historical work for many days.”17

Dubnow,

Ahad Ha’am, Bialik, and fellow intellectuals Yehoshua Rawnitzki and Mordechai Ben Ami, who were all

neighbors in Odessa, published an anonymous manifesto in Hebrew, penned by

Ahad Ha’am, which became a clarion call for Jewish self-defense:

Brothers.… It is a disgrace for five and a half million souls to

place themselves in others’ hands, to stretch out their necks and cry out for

help, without trying to defend themselves, their property, and the dignity of

their lives. And who knows if it was not this disgrace of ours that did not

cause the start of our degradation in the eyes of all the people and to turn us

into the dirt in their eyes?… It is only he who knows

how to defend himself who is respected by others. If the citizens of this land

had seen that there is a limit, that we too, although we will not be able nor

willing to compete with them in robbery, violence, and cruelty, are nonetheless

ready and able to protect what is precious and sacred to us, until our last

drop of blood. If they had actually seen it, there is no doubt, they would not

have fallen upon us with such nonchalance; because

then a few hundred drunkards would not have dared to come with clubs and

pickaxes in their hands to a large community of Jews of some forty thousand souls

to kill and to violently rob to their hearts’ content. Brothers! The blood of

our brethren in Kishinev cries out to us: Shake off the dust and be men! Stop

whining and begging, stop reaching out to those who hate you and ostracize you,

that they should come and save you. Let your own hand defend yourself!18

Even after the

Kishinev pogrom, Dubnow retained his faith

that the Jews could achieve a life of dignity and meaning as a nation within

the framework of social and cultural autonomy in the Diaspora, in nation-states

where they were a minority. He considered the Jews the prototype for diaspora

nations and formulated his own radical doctrine for Jewish nationhood, writing:

When a people lose

not only its political independence but also its land when the storm of history

uproots it and removes it far from its natural homeland and it becomes

dispersed and scattered in alien lands, and in addition loses its unifying

language; if, despite the fact that the external national bonds have been

destroyed, such a nation maintains itself for many years, creates an

independent existence, reveals a stubborn determination to carry on its

autonomous development, such a people has reached the highest stage of

cultural-historical individuality and may be said to be indestructible, if only

it cling forcefully to its national will.19

Thus the idea that the Jewish people’s mobility

strengthens and deepens its culture, and that non-territorial nationhood is the

pinnacle of moral achievement because it is unencumbered by borders and the

monopoly over the use of force has become a pet thesis for liberals and

internationalists.

Letter in the handwriting of David Wolfson - on a

postcard with Lillien's work:

While

the Hibat Zion movement was sending pioneers to the Land of

Israel, Dubnow opposed the Zionist program

of securing territorial sovereignty, deeming it impractical. Amid the pogroms

sparked by the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881, he argued that

isolating the Jews in the backwater of Ottoman Palestine would degrade them

culturally and ethically, and they would “sink into Asiatic culture.” He wrote

to Moshe Leib Lilienblum, who had decided

to join the Lovers of Zion, that sovereignty was a “straw to clutch at, and

those who grasp at it will surely drown…in ignorance and barbarism.”20 He also

disagreed with his friend Ahad Ha’am’s idea that the Jews could

establish a center of modern life in Palestine. Dobnow

maintained that from a moral perspective, a diaspora national existence was

preferable to an exclusivist, territorial-sovereign

nationhood, which would inevitably cling to chauvinistic tribal nativism and

state violence.

Dubnow’s adherence to the idea of diasporic autonomism

was rooted in his faith that Russia would one day become a liberal,

multinational state. This remained his opinion up until the Russian democrats

surrendered to the Bolsheviks during the 1917 Revolution.

In 1922, he took

refuge in Berlin. Despite the failure of the Jews to integrate into Soviet

Russia and the early success of Zionism in Palestine and the Balfour

Declaration, Dubnow continued to believe

that the national future of the Jews lay in Europe. He rejected assimilation as

unnatural both psychologically and morally, and as a threat to the Jewish

people. Only a vibrant diaspora nation, united and organized, without territorial

sovereignty, could serve as the inspiration for a progressive, pluralist, and

multicultural society. Dubnow’s vision was

to build on the Jews’ proven success in keeping their ethnic particularity, via

their language, culture, and education, and their ability to maintain national

institutions. He wanted to revive the kahal system, but not based on religious

principles or hierarchy as it had been in the Middle Ages and in the Russian

Empire. The kahal he wanted to recreate would be of a democratic-republican

nature with a clearly secular national orientation. The Jewish diaspora nation

would serve as the model for multiethnic life in modern states whose

populations were not ethnically homogeneous and did not demand assimilation

into the predominant group.21

Even after the

pogroms of 1903 and other upheavals, Dubnow believed

Russia would become a multiethnic, liberal, democratic country in which the

Jews could flourish with national/non-territorial autonomy. After the 1905

Revolution, when elections for parliaments (Dumas) were first allowed, he

played a key role in the formation of the League for the Attainment of Full

Rights for the Jewish People of Russia. The goal of the league was “the

realization in the full measure of civil, political, and national rights for

the Jewish people.” It organized as a pressure group, not as a party, and

mobilized Jewish voters to ensure “the elections of candidates, preferably

Jewish, who would strive for full rights for the Jews and a democratic regime

of Russia.”22

Indeed, many Russian

Jews voted in the 1906 elections for the liberal party, the Kadet, because of its commitment to constitutional

order and universal suffrage. Thousands of Jews “who had previously no contact

with political life were now drawn into it by the exercise of their franchise.

Russian Jews could feel as they had never felt before that they had a stake in

the future of Russia.”23

By the time the

Bolsheviks seized power, almost all Russian Jews, who were officially

emancipated in the democratic 1917 February Revolution, were anti-Bolsheviks.

But when the Russian Civil War broke out and anti-Bolshevik forces of the White

Army committed anti-Jewish atrocities, many Jews adopted the Bolsheviks as

allies.24

As he saw fascism

rising in Europe and the Jewish national home in Palestine becoming a

reality, Dubnow still clung to his faith

that the diaspora nation would be the dominant mode of Jewish life, even if a

Jewish state were to be established. He did not agree that people must

constantly strive for sovereignty to be a nation. Dubnow was

murdered by a Latvian collaborator during the Nazi occupation of Riga in 1941.

For many, his cruel death became the symbol of the disaster inherent in the

naïve faith of living a secure Jewish life as a scattered diaspora nation.

I created the Jewish State

Only after the

appearance of Theodor Herzl on the world stage did Palestine become a central

focus of Jewish national sentiment. He laid the ideological and organizational

foundations for the Zionist movement. His pamphlet Der Judenstaat (The

Jewish State, 1896) called for the massive evacuation of Jews from Europe and

the restoration of a Jewish state in the Holy Land. The Jewish State was a

prophetic document, preaching the ingathering of exiles as the solution to the

Jewish Question in Europe, and granting the Jews equal status among the

nations.25

Herzl provided concrete

answers on how to transplant Jews from Europe to Palestine, and how to build

political and financial institutions, schools, and settlements. A charismatic

and relentless figure, he traveled the capitals of

Europe and beyond, building international backing of imperial powers and

alliances with other actors on the world stage. In many ways, Herzl is the

first modern Jewish statesman, who paved the way for diplomacy in Israel both

before and after statehood, and also for Diaspora

Jewry. In August 1897 Herzl presided over the First Zionist Congress in Basel,

Switzerland. After three days of remarkable deliberations, with hundreds of

enthusiastic Jewish delegates from seventeen countries in attendance, as well

as many non-Jews and European journalists, Herzl confided to his diary: “If I

were to sum up the Basel Congress in a single phrase, which I would not dare to

make public, I would say: in Basel I created the Jewish State.”

1. S. Zeitilin, “The Council of Four Lands,” The Jewish Quarterly

Review 39, no. 2 (1948), 212.

2. Benjamin

Pinkus, The Jews of the Soviet Union: The History of a National Minority

(Cambridge Russian, Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies, Series Number 62),1988, 12.

3. Salo Wittmayer Baron,

The Russian Jew under tsars and Soviets, 1976, 112.

4. Pinkus, Jews of

the Soviet Union, 16.

5. Benjamin Nathans,

Beyond the Pale: The Jewish Encounter with Late Imperial Russia (Studies on the

History of Society and Culture Book 45) Part of: Studies on the History of

Society and Culture (17 Books), 2002, 34.

6. Ibid.

7. Charles King,

Odessa: Genius and Death in a City of Dreams (New York: W. W. Norton & Co.,

2011), 97–106.

8. Louis

Greenberg, The Jews in Russia: The Struggle for Emancipation (Vol 1 & 2),

1987, 141.

9.

Michael Stanislawski, “Why Did Russian Jews Support the Bolshevik Revolution?”

Tablet, October 25, 2017.

10. Jonathan Frankel,

“The Jewish Socialism and the Bund in Russia,” in The History of the Jews of

Russia: 1772–1917, 255.

11. Anna Geifman has noted that in 1903 there were 136 million

people in the empire, including seven million Jews. See Anna Geifman, Thou Shalt Kill, Revolutionary Terrorism in

Russia, 1894–1917 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995), 32.

12. Simon

Rabinovitch, “The Dawn of a New Diaspora: Simon Dubnov’s Autonomism, from St.

Petersburg to Berlin,” Leo Baeck Institute Year Book 50, no. 1

(January 2005), 270.

13. Charles E. Woodhouse

and Henry J. Tobias, “Primordial Ties and Political Process in

Pre-Revolutionary Russia: The Case of the Jewish Bund,” Comparative Studies in

Society and History 8, no. 3 (April 1966), 331–360.

14. Zvi Gitelman,

“The Jews: A Diaspora within a Diaspora,” in Nations Abroad: Diaspora Politics

and International Relations in the Former Soviet Union, eds. Charles King and

Neil Melvin (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1998), 61.

15. Joshua M. Karlip, The Tragedy of a Generation: The Rise and Fall of

Jewish Nationalism in Eastern Europe (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press,

2013), 10.

16. Gitelman,

“The Jews: A Diaspora within a Diaspora,” 61.

17. Simon Dubnow, “Ahad Ha’am’s Scroll of Mysteries (25

Years Since the Kishinev Massacre),” Hatekufah 24

(1934), 416.

18. Ibid., 416–420.

19.

Rabinovitch, The Dawn of a New Diaspora:

Simon Dubnov's Autonomism, from St. Petersburg to Berlin August 2005 The Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook 50(1):267-288281.

20. Miriam Frenkel,

“The Medieval History of the Jews in Islamic Lands: Landmarks and Prospects,” Peamim 92 (2002), 32.

21. After Dubnow wrote the “Diaspora” entry in the Encyclopedia

of Social Sciences in the 1930s, the term “diaspora” became almost exclusively

linked to the history of and political sociology of the Jews.

22. Sidney Harcave, “Jews and the First Russian National Election,”

The American Slavic and European Review 9, no. 1 (February 1950), 33–41.

23. Ibid., 41.

24.

Michael Stanislawski, “Why Did Russian Jews Support the Russian Revolution?,” Tablet, October 25, 2017.

25. Aharon Klieman,

“Returning to the World Stage: Herzl’s Zionist Statecraft,” Israel Journal of

Foreign affairs 4, no. 2 (2010), 76.

For updates click hompage here