By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The Problem With Israel

And Hamas

Israel’s devastating

response to Hamas’s shocking October 7 attack

has produced a humanitarian catastrophe. During the first 100 days of war

alone, Israel dropped the kiloton equivalent of three nuclear bombs on the Gaza

Strip, killing some 24,000 Palestinians, including more than 10,000 children;

wounding tens of thousands more; destroying or damaging 70 percent of Gaza’s

homes; and displacing 1.9 million people—about 85 percent of the territory’s

inhabitants. By this point, an estimated 400,000 Gazans were at risk of

starvation, according to the United Nations, and infectious disease was

spreading rapidly. During the same period in the West Bank, hundreds of

Palestinians were killed by Israeli settlers or Israeli troops, and more than

3,000 Palestinians were arrested, many without charges.

Almost from the

outset, it was clear that Israel did not have an endgame for its war in Gaza, prompting the United States to

fall back on a familiar formula. On October 29, just as Israel’s ground

invasion was getting underway, U.S. President Joe Biden said, “There

has to be a vision for what comes next. And in our view, it has to be a

two-state solution.” Three weeks later, after the extraordinary devastation of

northern Gaza, the president said again, “I don’t think it ultimately ends

until there is a two-state solution.” And on January 9, after more than three

months of war, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken took up the refrain

again, telling the Israeli government that a lasting solution “can only come

through a regional approach that includes a pathway to a Palestinian state.

These calls to revive

the two-state solution may come from good intentions. For years, a two-state

solution has been the avowed goal of U.S.-led diplomacy, and it is still widely

seen as the only arrangement that could plausibly meet the national aspirations

of two peoples living in a single land. Establishing a Palestinian state

alongside Israel is also the principal demand of most Arab and Western

governments, as well as the United Nations and other international bodies. U.S.

officials have therefore fallen back on the rhetoric and concepts of previous

decades to find some silver lining in the carnage. With the unspeakable horrors

of the October 7 attack and the ongoing war on Gaza making clear that the

status quo is unsustainable, they argue that there is now a window to achieve a

larger settlement: Washington can both push the Israelis and the Palestinians

to finally embrace the elusive goal of two states coexisting peacefully side by

side and at the same time secure normalization between Israel and the Arab

world.

But the idea of a

Palestinian state emerging from the rubble of Gaza has no basis in reality.

Long before October 7, it was clear that the basic elements needed for a

two-state solution no longer existed. Israel had elected a right-wing

government that included officials who were openly opposed to the two states.

The Palestinian leadership recognized by the West—the Palestinian Authority

(PA)—had become deeply unpopular among Palestinians. And Israeli settlements

had grown to the extent that creating a viable, contiguous Palestinian state

had become almost impossible. For nearly a quarter century, there had also been

no serious Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, and no major constituency in

Israeli politics supported resuming them. Hamas’s shocking attack on Israel and

Israel’s subsequent months-long obliteration of Gaza has only exacerbated and

accelerated those trends.

The principal effect

of talking again about two states is to mask a one-state reality that will

almost surely become even more entrenched in the war’s aftermath. It would be

good if the Israelis and the Palestinians could negotiate a peaceful division

of land and people into two sovereign states. But they cannot. In repeated

public statements in January, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin

Netanyahu made clear not just that he opposes a Palestinian state but also

that there will continue to be, as he put it, “full Israeli security control

over all of the territory west of the Jordan [River]”—land that would include

East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza. In other words, Israel seems likely to

continue to rule over millions of Palestinian noncitizens through an

apartheid-like governance structure in which those Palestinians are denied full

rights in perpetuity.

Israel’s politicians

bear most of the responsibility for this grim reality as it developed over

decades, aided by weak Palestinian leaders and indifferent Arab governments.

But no external party shares more blame than the United States,

which has enabled and defended the most right-wing government in Israel’s

history. The Biden administration cannot create peace just by calling for it.

But it could recognize that its rhetoric about a two-state future has failed

and shifted toward an approach focused on dealing with the situation as it is.

This would entail making sure that Israel adheres to international law and

liberal norms for all people in the territories under its control, upholding

Biden’s pledge to promote “equal measures of freedom, justice, security, and

prosperity for Israelis and Palestinians alike.” Such an approach, which would

bring U.S. policy more in line with its avowed aspirations, would be far more

likely to protect and serve both the Israelis and the Palestinians—and support

global U.S. interests.

The Makings Of Mayhem

Hamas’s horrific October

7 attack has sometimes been described as an “invasion” in which militants

breached the “border” between Israel and Gaza. But there is no

border between the territory and Israel, any more than there is a border

between Israel and the West Bank. Borders demarcate lines of sovereignty

between states—and the Palestinians do not have a state.

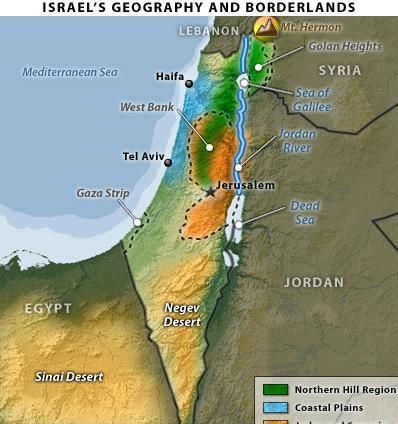

The Gaza Strip came

under Egyptian control during the 1948 war when the state of Israel was

established. In 1967, Israel conquered Gaza, along with the West Bank, the

Sinai Peninsula, and the Golan Heights. Over the next 26 years, Israel directly

governed the small, densely packed strip, introducing Jewish settlements as it

did in the other territories it captured. In 1993, following the Oslo Accords, Israel handed over some daily

management of Gaza to the PA but retained effective domination with a permanent

military presence, control over its land perimeter and airspace, and oversight

of its finances and tax revenues.

In 2005, Israeli

Prime Minister Ariel Sharon decided to unilaterally withdraw from Gaza and

dismantle Israeli settlements there. But that did not change the fundamental

realities of occupation. Although the Palestinians were left to determine the

internal governance of the strip, Israel retained absolute power over shared

boundaries, shorelines, and airspace, with Egypt policing Gaza’s sole border

along the Sinai Peninsula, closely coordinating with Israel. As a result,

Israel, with Egyptian assistance, controlled everything that went in or out of

Gaza—food, building supplies, medicine, and people.

After Hamas won

elections in Gaza in 2006 and then consolidated power there in 2007, the

Israeli government found it useful for the Islamist organization to police the

strip indefinitely, thus leaving the Palestinians with divided leadership and

defusing international pressure on Israel to negotiate. Meanwhile, Israel

imposed a blockade on the territory, effectively cutting it off from the rest

of the world. Hamas, in turn, significantly expanded the system of underground

tunnels it had inherited from Israel to circumvent the blockade, strengthen its

hold on Gaza’s economy and politics, and build its military capabilities.

Episodic eruptions of conflict—usually involving rocket barrages by Hamas

followed by retaliatory strikes by Israel—allowed Hamas to demonstrate its

resistance credentials and Israel to show that it was “mowing the grass,”

degrading Hamas’s military capabilities and infrastructure and often killing

hundreds of civilians without challenging the organization’s internal control.

Gaza’s young population suffered under the blockade and the intermittent

violence, but Hamas maintained a lock on power.

In the years leading

up to October 7, this status quo in Gaza—and the parallel administration of the

West Bank by an enfeebled PA—seemed deplorable but sustainable to many

observers in both the region and the West. Thus, the Biden administration could

simply set aside the Palestinian issue in its push for normalization between

Israel and Saudi Arabia; Israeli politicians could bicker over anti-democratic

judicial reforms and Netanyahu’s power grabs, even as a sustained Israeli

protest movement largely overlooked the government’s creeping annexation of the

West Bank. The shock and outrage provoked by Hamas’s brutal attack and Israel’s

extraordinary retaliation shattered that illusion, making clear that ignoring a

demonstrably unjust situation was not only unsustainable but highly dangerous

and that the regional order could not be remade without acknowledging the

plight of the Palestinians.

Neither Two States Nor One

As the war in Gaza

has unfolded, many Israelis have argued that there can be no return to the

status quo, by which they mean no cease-fire without the total “destruction” of

Hamas. But the alternatives to Hamas rule that Israeli leaders have proposed

are very much a continuation of the existing situation. Israel is not suddenly

conquering Gaza: it never ceased controlling it, a reality that is all too

present for Gazans who have suffered for 17 years under the Israeli blockade.

It is more accurate to say that Israel, which has been the sovereign occupying

power in Gaza for 56 years under a variety of political configurations, is once

again attempting to rewrite the rules of its domination. And as the Israeli

government has made clear, it has no intention of pursuing a renewed quest for

a Palestinian state.

Israelis had soured

on a two-state solution long before October 7. Over the past decade, the

Israeli peace camp, represented by the Meretz Party, had declined electorally

to the point of near elimination; in 2022, it failed to cross the electoral

threshold for Knesset representation. The current Israeli government had all

but disavowed a two-state outcome and included right-wing members who openly

aspired to full annexation of Gaza and the West Bank. October 7 accelerated the

trend. The Israeli public has overwhelmingly lost what little faith remained in

a two-state outcome, as a settler movement intent on dominating all the land

between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea has relentlessly risen to

power.

Some would argue that

those settlers wield such influence only because Netanyahu relies on them to

stay in power. But the problem is much greater. Most Israelis today are

similarly uninterested in either a two-state solution or a one-state solution

based on equality for all residents in the territory under Israeli control;

many also feel that the October 7 attack confirmed their worst fears about the

Palestinians. Whether acknowledged or not, the rejection of both a two-state

outcome and a single state based on equality for all leaves two possibilities:

the further entrenching of Jewish supremacy and apartheid-like controls over a

non-Jewish population that will soon outnumber Jewish Israelis, or the

large-scale transfer of Palestinians from the land, as some Israeli cabinet

ministers have openly called for.

On the Palestinian

side, the stature of the PA, which has been key to Washington’s thinking about

postwar Gaza, has crumbled. Along with its inability to stem Israeli policies,

it is plagued by perceptions of corruption and the lack of an electoral mandate.

Today, hardly any Palestinians still support PA President Mahmoud Abbas. (One

poll conducted in late November during the brief cease-fire in Gaza placed his

support at seven percent.) Meanwhile, Hamas’s popularity among the

Palestinians, particularly in the West Bank, has risen. Recent polling shows

that there is still some support for a two-state solution among the

Palestinians but virtually no confidence in the United States to deliver it.

This is the stark

political reality that those who push for a two-state negotiating framework

will face. Neither the leadership nor the public on either side supports such a

process. The facts on the ground—a vast and ever-growing Israeli security and

road infrastructure designed to connect and protect Jewish settlements across

the West Bank, combined with the near-complete destruction of Gaza—make a

viable Palestinian state almost inconceivable. And the United States has given

no sign that it is willing to exert the power necessary to overcome those

obstacles.

Some now lament that

October 7 struck mortal blows to both the two-state solution and a just and

peaceful one-state alternative. But neither had been on offer. The main effect

of the war thus far has been to lay bare and dramatically increase the injustices

of a single state based on the economic, legal, and military subjugation of one

group by another—a situation that violates international law and offends

liberal values. This is the situation that must be confronted before the

question of two states can be broached. And it is here that the United States

could make a significant difference.

Critical Conditions

Instead of pushing

for a two-state outcome that has almost no prospect of materializing,

Washington should recognize the current reality and use its influence to

enforce adherence to international laws and norms by all parties. The United

States has long avoided holding Israel to those standards; the Biden

administration has gone further, shielding Israel from the United States’ own

laws. (In January, an investigation by The Guardian found that

since 2020, the U.S. State Department had used “special mechanisms” to continue

providing weapons to Israel despite a U.S. law prohibiting assistance to

foreign military units involved in gross human rights violations.) That needs

to change. Simply by upholding the rules-based liberal international order,

Washington could do much to mitigate the darkest injustices of the present

situation. Such an approach would not be about Washington dictating what the

Israelis and the Palestinians should do. Rather, it is about ending

the anomalous practice of using significant U.S. resources to empower behavior

that the U.S. finds objectionable and that even conflicts with U.S. interests.

A rules-based

approach to managing the postwar situation in Gaza, the West Bank, and East

Jerusalem would need to involve several components. First, the United States

should abandon its refusal (at least as of this writing) to call for a

cease-fire and seek an end to the war in Gaza and the return of Israeli

hostages as quickly as possible. A cease-fire would stop the daily killing of

hundreds of Palestinians and allow for humanitarian assistance to enter the

territory, forestalling the rapid spread of famine and infectious disease. It

would also end Hamas’s rocket fire at Israel, de-escalate tensions with

Hezbollah on the Israeli-Lebanese border, and allow displaced Israelis to

return to their border towns. And it might even lead Yemen’s Houthis to

end their campaign against Red Sea shipping, which has perilously widened the

war. (Both Hezbollah’s leader, Hassan Nasrallah, and members of the Houthis

have said in public statements that they would stop attacks in the event of a

cease-fire, and Nasrallah has asserted that attacks against U.S. forces in Iraq

and Syria by Iranian-backed militias would also end.)

By failing to call

for a cease-fire throughout the fall of 2023 and into 2024, the Biden

administration not only allowed the war to spread dangerously but also

emboldened Israel’s far-right government to significantly augment its

repression and destruction of Palestinian communities, including in the West

Bank and East Jerusalem. If Biden is unable to demand an end to the war at a

time when there is near-global unanimity on the need for a cease-fire, and a

clear majority of Americans—some three in five according to a late December

poll—support such a step, he will hardly be able to position the United States

to provide bold leadership for the so-called day after.

But a cease-fire

alone is not enough to end deeply unlawful conduct. The excesses of the war on

Gaza have been so extreme that to many international observers, they have left

international law in tatters. One outcome has been to isolate Washington and undermine

its claim of defending international norms and the liberal international order.

The fact that South Africa, one of the leaders of the global South, has accused

Israel of the extraordinary charge of genocide before the International Court

of Justice suggests the extent to which many parts of the world are no longer

in line with Washington and its Western allies, undermining U.S. leadership in

international institutions. In a preliminary ruling on January 26, the court

determined that some alleged Israeli actions in Gaza plausibly constitute

violations of the UN Genocide Convention. Although the court did not demand a

cease-fire, it ordered a sweeping set of measures Israel must undertake to

limit harm to Palestinian civilians. If Washington continues unconditional

support for Israel in Gaza without demanding adherence to those measures, it

may appear even more complicit in the war. The United States must support

international accountability for alleged war crimes on all sides.

Following a

cease-fire, the United States must get serious about pushing Israel to shift

course. So far, U.S. policymakers’ efforts to outline a postwar plan for Gaza

have been repeatedly rebuffed by Israeli officials. Israel has dismissed the

idea of returning the PA to Gaza, which is a cornerstone of current U.S.

strategy. Instead, Israeli politicians talk openly about restoring illegal

settlements and creating a buffer zone in northern Gaza and seem intent on

forcing large numbers of Palestinians out of the territory—notions that flout

explicit American redlines. Meanwhile, Netanyahu’s government has

systematically ignored even the most anonymous requests to minimize the killing

of civilians, allow for the delivery of humanitarian aid, plan for a postwar

Gaza, and help rebuild the PA. Israel’s current strategy seems likely to end in

either the mass expulsion of Gazans or a perpetual, costly, and violent

counterinsurgency. The United States has actively opposed the former, in line

with the forcefully expressed positions of its allies in Jordan and Egypt, and

the latter would only be made worse the longer Israeli troops remain in Gaza.

But the Biden administration has refused to impose any consequences to attempt

to compel Israel to accept those demands.

To overcome Israeli

intransigence, the United States must stop shielding Israel from the

consequences of severe violations of international law and norms at

the United Nations and other international organizations. Such a step

in itself could start an essential policy debate within Israel and among the

Palestinians, which could open up new possibilities. At the same time, the

White House should condition further aid to Israel on adherence to U.S. law and

international norms and should encourage similar efforts in Congress instead of

opposing them. It should also instruct U.S. government agencies to follow the

law and international rules in providing assistance to Israel rather than

seeking creative ways to subvert them.

Indeed, Biden’s

reluctance to tie military aid to Israel to human rights or even to U.S. law

has already led to extraordinary moves by members of his party. Consider the

resolution proposed in December by Maryland Senator Chris Van Hollen, a

Democrat, and 12 of his colleagues to condition supplemental military aid to

Israel and Ukraine on the requirement that weapons are used by U.S. law,

international humanitarian law, and the law of armed conflict. Similarly,

Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, an independent, proposed a resolution that

would make military aid to Israel contingent on a U.S. State Department review

of possible human rights violations in the war. But as has already been shown

with the defeat of Sanders’s proposal in January, such efforts are unlikely to

succeed without presidential leadership, especially in an election year in

which congressional Democrats are reluctant to undermine the electoral

prospects of their already unpopular president. Only the White House can

successfully lead on this issue.

Rules For Reality

Paradoxically, the

traumas experienced by the Palestinians and the Israelis since October 7 have

demonstrated both the urgent need for a two-state solution and the

improbability of establishing one. The White House could still try if it were

willing to use American muscle to reopen a path to a Palestinian state. But

nothing in its current approach suggests it will do more than continue to offer

lip service to the goal while enabling the horrific reality.

The pain and shock of

war for both the Israelis and the Palestinians could propel internal

reassessments—and new leadership—on both sides at a time when no other good

outcome is in view. Perhaps Biden may be able to rally Arab states to normalize

relations with Israel, as the White House so desperately wants, on the

condition that Israel agree to a two-state process. But few Palestinians, or

other parties that might be involved in such a plan, seem likely to trust U.S.

leadership, given the administration’s record during and preceding the war.

American credibility in the Middle East is at an all-time low.

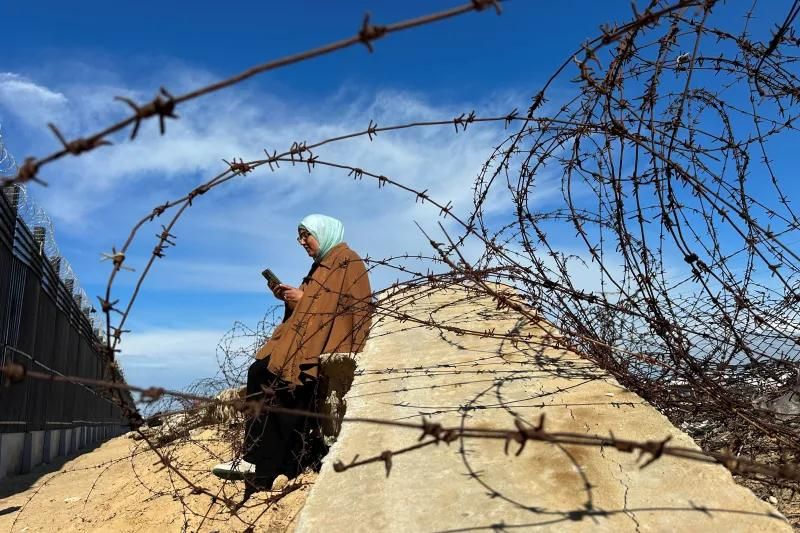

A displaced Palestinian in Rafah, Gaza Strip, February

2024

At this juncture, any

two-state initiative would need to deliver concrete, upfront results to have

even a chance of success. Those tangible benefits would need to be weighted

more heavily toward the Palestinians, given the extremity of their circumstances.

For example, Biden could immediately recognize a Palestinian state in the West

Bank and Gaza, commit to no longer defending Israeli settlements at the United

Nations, and make military aid to Israel conditional on Israel adhering to

international law and refraining from any actions that undermine a Palestinian

state. The United States could also pledge to guarantee Israeli security within

Israel’s internationally agreed-on borders. But it is highly unlikely that

Israel would accept any of these terms, and there is nothing in Biden’s history

to suggest he is capable of applying the necessary pressure to carry them out.

Advocates of a renewed

push for a two-state solution will claim that it is the most realistic option.

It manifestly is not. No matter how the war in Gaza ends, it is improbable that

a two-state solution—or an equitable one-state solution, for that matter—will

be on offer. Indeed, there is no immediate path forward without first coming to

terms with the darker one-state reality that Israel has consolidated. U.S.

policy, therefore, should be centered not on implausible efforts to revive

talks of unachievable outcomes but on forcefully spelling out the legal and

human rights standards it expects to be met. Washington can use its power to

oppose conditions and policies it will not support, whether that is the

expulsion of Palestinians from Gaza, the continued seizure of Palestinian land

in the West Bank, or the continuation and deepening of an apartheid-like system

of military administration in Palestinian areas. Those limits must be made

clear, and they must be enforced. The United States should back international

justice mechanisms and accountability for war crimes by all parties. It should

demand adherence to international human rights law and norms in the treatment

of all people under Israel’s effective control, whether or not they are Israeli

citizens. And it must refuse to continue business as usual with any government

that violates these standards.

In setting concrete

legal boundaries for the present situation, the United States would regain some

of the credibility it has lost in the Middle East and the global South. By

bringing the current reality more in line with international law, Washington could

begin to create the conditions in which a better political landscape could one

day emerge. It’s time for the U.S. government to take responsibility for the

failed approach that has led to this devastating war. Decades of exempting

Israel from international standards while pursuing empty and toothless talk of

an unattainable two-state future has severely undermined the United States’

standing in the world. Washington should stop using its power to enable blatant

violations of international rights and norms. Until it does so, a profoundly

unjust and illiberal status quo will continue, and the United States will be

perpetuating the problem rather than solving it.

For updates click hompage here