By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Israelis and Arabs

have been fighting over Gaza on and off, for decades. It's part of the wider

Arab-Israeli conflict.

After World War II

and the Holocaust in which six million Jewish people were killed, more Jewish

people wanted their own country.

They were given a

large part of Palestine, which they considered their traditional home but the

Arabs who already lived there and in neighboring countries felt that was unfair

and didn't accept the new country.

In 1948, the two

sides went to war. When it ended, Gaza was controlled by Egypt and another

area, the West Bank, by Jordan. They contained thousands of Palestinians who

fled what was now the new Jewish home, Israel.

To know the context

of what follows start

with the overview here, and for reference list of personalities involved.

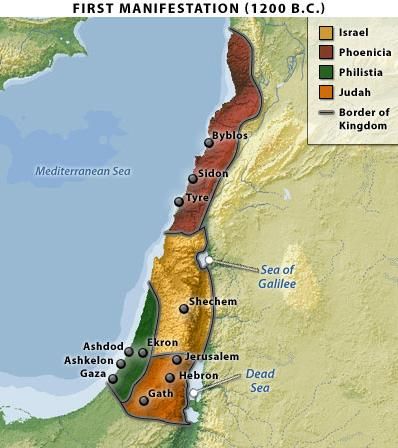

The Land that is Israel

Figuratively speaking one could say

that 'Israel' has manifested itself three times in history. The first

manifestation began with the invasion led by Joshua and lasted through its

division into two kingdoms, the Babylonian conquest of the Kingdom of Judah and

the deportation to Babylon early in the sixth century B.C. The second

manifestation began when Israel was recreated in 540 B.C. by the Persians, who

had defeated the Babylonians. The nature of this second manifestation changed

in the fourth century B.C., when Greece overran the Persian Empire and Israel,

and again in the first century B.C., when the Romans conquered the region.

To understand the complexity of Israel's founding, we

must first delve into the region's rich and layered history before the 20th

century. The ancient kingdom of Israel, founded around the 11th century BCE,

became the first organized Jewish state, while its southern neighbor, the

Kingdom of Judah, would later become the nucleus of Jewish religious and

cultural identity These kingdoms fell to successive empires—the Assyrians,

Babylonians, Persians, and finally the Romans. Jewish rebellion against Roman

rule culminated in the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE and the mass

dispersion of Jews throughout the Roman Empire, a key event known as the Jewish

Diaspora.

During the long

centuries of the Diaspora, Jews maintained a deep connection to the land of

Israel, even as the region passed under the control of various empires,

including the Byzantine, Islamic Caliphates, Crusaders, Mamluks, and the

Ottoman Empire. Despite periods of persecution and exile, small Jewish

communities continued to exist in cities such as Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed, and

Tiberias. Yet, the majority of Jews lived in Europe, North Africa, and the

Middle East, maintaining their religious and cultural traditions while yearning

for a return to their ancestral homeland—a central theme of Jewish prayer and

identity.

By the late 19th

century, the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, which had ruled the region for

centuries, signaled a new era of political upheaval and opportunity. The

region's strategic location, situated at the crossroads of Africa, Europe, and

Asia, meant that it attracted the interest of European powers, particularly

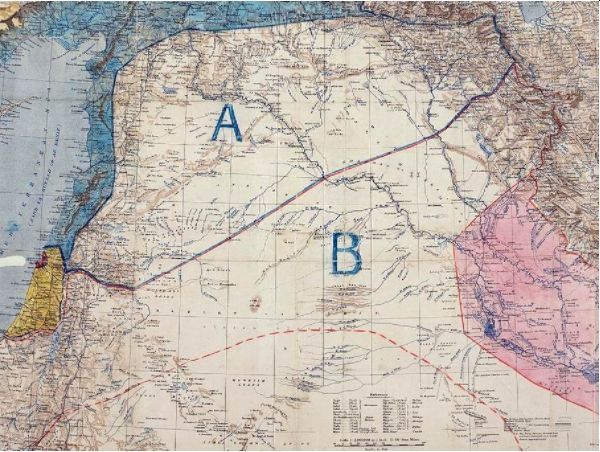

Britain and France, which sought to expand their colonial empires. The Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916, negotiated in secret

between Britain and France, would later divide the Ottoman territories into

spheres of influence, including Palestine, where Britain assumed control

after World War I.

This period also

witnessed the rise of Arab nationalism, as the Arab population of the region,

inspired by the weakening of the Ottoman Empire and European colonialism, began

to assert its political aspirations. The desire for self-determination, led by Sharif Hussein coupled with resentment

towards European colonial powers, would create the foundation for

Arab resistance to the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine.

The 19th century,

moreover, saw the beginning of a new chapter in Jewish history with the

emergence of modern nationalism, particularly Zionism, as Jews in Europe faced

increasing discrimination, persecution, and the challenges of assimilation.

This rising Jewish nationalist movement would ultimately shape the trajectory

of Jewish immigration to Palestine and lay the groundwork for the creation

of the State of Israel.

The Rise of Zionism

Zionism, the movement

for the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, arose in the late 19th

century in response to the twin pressures of European anti-Semitism and the

rise of nationalist movements across Europe. The term "Zionism" was coined by

Theodor Herzl, an Austrian-Jewish journalist and writer, in the late 19the

century, though the roots of Jewish yearning for a return to Zion (another

name for Jerusalem and the land of Israel) date back to ancient times.

Theodor Herzl, who

witnessed firsthand the virulent anti-Semitism of European society—most

notably during the Dreyfus Affair in France

—became convinced that the only solution to the "Jewish Question" was

for Jews to have their own nation-state. His landmark book, Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State), published in 1896, laid out

the ideological foundation of political Zionism. Herzl argued that Jews,

like other national groups in Europe, deserved the right to self-determination

and that this could only be achieved through the establishment of a sovereign

Jewish state in Palestine.

Zionism was not a

monolithic movement, however, and various factions emerged with differing

visions of what the future Jewish state should look like. Some early Zionists,

like Ahad Ha'am, promoted a cultural Zionism that

emphasized the revival of Hebrew and Jewish culture as Che basis for a

Jewish homeland, rather than the establishment of a political state.

Others, like Labor Zionists led by figures such as David Ben-Gurion, sought to

combine Zionist ideals with socialist principles, advocating for collective

agriculture (kibbutzim) and the building of a new Jewish society based on

equality and labor.

In the early years of

the Zionist movement, Jewish migration to Palestine was limited, but it gained

momentum with the waves of pogroms and anti-Semitic violence in

Eastern Europe, particularly in Russia, during the late 19th and early

20th centuries. This period saw the arrival of the First

Aliyah (Jewish immigration wave) in the 1880s, during which thousands of

Jews, many from Eastern Europe, settled in Palestine. These early settlers

faced significant hardships, including disease, economic instability, and

resistance from the local Arab population, but they laid the groundwork for

future Jewish immigration and state-building efforts.

For the early

Zionists, democratic values were embedded in a number of prior questions, many

of them complex and charged with emotion. Zionists

asked themselves if they should choose Palestine or some other country, if

they should start collective farms or promote private enterprise. Another

question was even more fundamental: Should immigration be organized en masse, by a sovereign Zionist

"corporation," though any such method of settling the Jewish national

home was bound to produce a mix of European languages there? Or should priority

be given to supporting small groups of cultural pioneers who were devoted to

evolving modern Hebrew, however gradually? Should Zionism wait for support from

the imperial powers or go it alone in small vanguard groups?

The early 20th

century witnessed further waves of Jewish immigration (the Second and Third

Aliyot), as Zionist pioneers established agricultural communities and cities

like Tel Aviv, seeking to fulfill the Zionist dream of building a Jewish

homeland. The Zionist movement also began to garner support from sympathetic

elements within European society, including some Christian Zionists who saw the

return of Jews to Palestine as part of a religious prophecy.

At the same time, Arab resistance to Jewish immigration and land

acquisition began to grow. The Arab population, which had lived in Palestine

for centuries under Ottoman rule, increasingly viewed Zionism as a threat to

their land, livelihoods, and national aspirations. Tensions between Jewish and

Arab communities escalated in the early decades of the 20th century, setting

the stage for future conflict as both groups sought to assert their claims to

the land.

European colonialism

played a pivotal role in shaping the modern

history of the Middle East, particularly in the decades leading up to the

founding of Israel. By the late 19th century, European powers had carved up

much of the world into colonial possessions, and the Middle East was no

exception. Britain and France, in particular, were major players in the region,

driven by their desire to control trade routes, access natural resources, and

extend their

The decline of the

Ottoman Empire, long referred to as the "sick man of Europe/ created an

opening for European intervention in the Middle East. During World War I, the

British and French made secret agreements (such as the Sykes-Picot Agreement)

to divide the Ottoman territories into spheres of influence. Following the

defeat of the Ottomans, the League of Nations granted Britain the

mandate to govern Palestine, a development that would have lasting

consequences for the region.

The resolution on Syria adopted

by the Eastern Committee one week later nevertheless completely disregarded

Cecil’s (and Hirtzel’s) warning. It contained a maximalist program, which

envisaged British predominance in Syria, and expected the French to give up

their rights under the Sykes–Picot agreement in area ‘A’, and even the Syrian

parts of the blue zone, in order that an ‘autonomous Arab State, with capital

at Damascus’ would have access to the sea. In exchange, Britain was

magnanimously prepared to ‘support the French claims to a special position in

the Lebanon and Beirut […] and at Alexandretta’, keeping in mind that it was

‘essential that no foreign influence other than that of Great Britain should be

predominant in areas A and B’.

The British Mandate in Palestine, which lasted from 1920

to 1948, was marked by a delicate balancing act as Britain tried to manage the

competing aspirations of Jews and Arabs in the territory. Britain had, through

the Balfour Declaration of 1917, expressed support for the establishment of a

"national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine. This declaration,

while vague in its terms, was seen by the Zionist movement as a

significant step toward realizing their goal of Jewish statehood.

However, Britain's

commitment to Zionism was tempered by its need to maintain stability in the

region, particularly as Arab resistance to Jewish immigration grew more

intense. Arab revolts in the 1920s and 1930s, fueled by opposition to Jewish

land purchases and fears of displacement, led Britain to issue a series of

White Papers that attempted to limit Jewish immigration and land acquisition.

These policies, in

turn, angered the Zionist movement, which viewed them as a betrayal of

Britain's earlier commitments.

The outbreak of World

War II and the Holocaust had a profound impact on the trajectory of Zionism and

the future of Palestine. The mass murder of six million Jews during the

Holocaust galvanized support for the establishment of a Jewish state, both

within the Jewish community and among sympathetic Western powers, particularly

the United States. The war also marked the decline of European

colonialism, as Britain and France, weakened by the conflict, began to retreat

from their colonial possessions.

In the post-war

period, international sympathy for the Jewish people, combined with the

strategic interests of the Western powers, paved the way for the United Nations

to propose a partition plan for Palestine in 1947. This plan, which called for

the creation of separate Jewish and Arab states, was accepted by the Zionist

leadership but rejected by the Arab states and Palestinian Arab leaders. The

subsequent war in 1948, which followed the declaration of the State of Israel,

resulted in the establishment of Israel and the displacement of hundreds of

thousands of Palestinian Arabs—a conflict that continues to resonate in the

region to this day,

European colonialism,

therefore, played a critical role in shaping the modern Middle East and the

conditions that led to the founding of Israel. The legacy of colonialism, with

its arbitrary borders, foreign intervention, and the imposition of external political

models, has left a lasting imprint on the region, contributing to the ongoing

conflicts and struggles for national identity and sovereignty.

For updates click hompage here