By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

On 6 May 2017, the US

Senate unanimously passed a resolution that commemorates the 50th

anniversary of the reunification of Jerusalem. “Jerusalem should remain the

undivided capital of Israel in which the rights of every ethnic and religious

group are protected,” the resolution states, adding that “there has been a

continuous Jewish presence in Jerusalem for 3 millennia.” It also says that

“Jerusalem is a holy city and the home for people of the Jewish, Muslim and

Christian faiths.” Furthermore, the text advocates a two-state outcome based on

direct negotiations between Israelis and Palestinians.

Followed today by a hefty debate during an emergency meeting at the UN Security Council.

What it came down to is that the U.N. basically rejects Trump's recognition of Jerusalem as Israeli

capital.

Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, and Iran denounced the U.S. move, as some

protesters took to the streets of Amman and other provinces as well as

Palestinian camps, according to news websites. United Nations Secretary-General

Antonio Guterres said he rejected unilateral steps that jeopardize peace.

Qatar’s Emir Sheikh Tamim Al Thani told Trump that declaring Jerusalem Israel’s

capital will erode stability in the Middle East, Al-Jazeera television

reported.

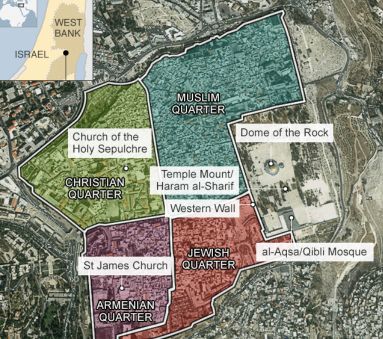

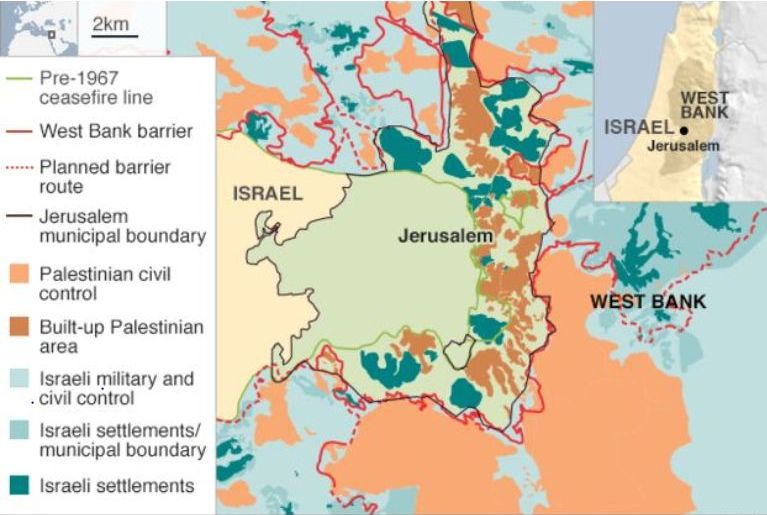

Thus Jerusalem, united under Israeli rule since 1967 with free access

for Muslims, Christians, and Jews to all their holy sites (except the

Wakf-dominated Temple Mount itself, where access for Christians and Jews is

limited), is now again on the chopping block as it is also claimed by

Palestinians as the capital of a future state.

But while a first reaction was that this means a two-state solution is

off the table, there would still be the possibility of negotiations that would allow East Jerusalem to be a

Palestinian capital.

Also the present US Governement declared

Jerusalem to be Israel’s capital, it didn’t call it the undivided capital of

Israel, leaving the door open for Israelis and Palestinians to

divide the city during any final status negotiations between the two.

Dennis Ross the former American envoy to the Middle East writes in an

article published by Foreign Policy:

"The announcement, they should underline, is about recognizing what

no one questions: that any peace deal would end with Israel maintaining its

capital in at least part of Jerusalem. That would help make clear the

administration’s contention that it is not putting its thumb on the scale

against Palestinian interests in Jerusalem, the United States continues to

insist that the basic issues related to the future of Jerusalem, the questions

of sovereignty, and competing for Israeli and Palestinian claims must be

subject to negotiations before there can be a peace agreement. Both elements of

this message need to be a mantra, repeated to Arabic audiences by top U.S.

officials in the weeks ahead, including by Vice President Mike Pence when he

visits the region.

This is the best hope for strengthening the hands of the Arab and

Palestinian leaders who must resist the efforts of those like Hamas who will

seek to distort the reality and claim that Jerusalem has been given away, and

who clearly want to provoke violence and greater polarization. It can also

begin to change the environment in a way that allows Abbas and his negotiators,

such as Saeb Erekat, to walk back from some of their statements about ending

the peace process and the American role in it.

Conveying this message is not just important to avert violence, but also

to ensure that the plan that the Trump administration intends to present to the

Israelis, Palestinians, and Arab countries is not dead on arrival. The reason

former Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama invoked the

waiver was not because they lacked courage but because they believed this would

deny the Palestinians and the Arabs the political space they needed to make

hard decisions for peace, thus rendering its achievement more difficult.

President Trump argued in his statement that they were wrong. If he wants to

prove he is right, he will first need to make clear that their interests and

rights have not already been conceded, and then present a credible peace plan,

including on Jerusalem."

Khaled Elgindy who was a Palestinian

advisor on the other hand thinks it is already too late, because the Saudis are

seen on board with U.S. peace efforts.

A short history of Jerusalem

and how the problem could be solved.

What initially opened a new era in the history of Jerusalem is when,

ending Ottoman rule, British troops led by General Allenby entered Jerusalem on

11 December 1917.

In the middle of October British officials already foresaw ‘proposals for an international Gendarmerie and

even perhaps an international provisional government for Palestine’.

Allenby dismounted and entered the city on foot through the Jaffa Gate,

together with his officers, in deliberate contrast to the perceived arrogance

of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s entry into Jerusalem on horseback in 1898 which was not

well received by the local citizens. He subsequently stated in his official

report:

…I entered the city officially at noon, 11 December, with a few of my

staff, the commanders of the French and Italian detachments, the heads of the

political missions, and the Military Attaches of France, Italy, and America…

The procession was all afoot, and at Jaffa gate I was received by the guards

representing England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, Australia, New Zealand, India,

France and Italy. The population received me well…”

Allenby received Christian, Jewish, and Muslim community leaders in

Jerusalem and worked with them to ensure that religious sites of all three

faiths were respected. Reflecting his desire to avoid having his campaign being

presented as a religious war, Allenby sent his Indian Muslim Soldiers to guard

Islamic religious sites, feeling that this was the best way of reaching out to

the Muslim population of Jerusalem.

On 17 December Chaim Weizmann submitted a short memorandum on why a

Zionist commission, headed by him, should go to Palestine ‘as soon as possible’.

For the Jews who under Ottoman rule moved to what then became Israel,

they and those who came later perceived their relationship with Jerusalem as

going back to pre-Roman times. And might point to the “Arch of Titus” in Rome

completed in 81 CE, where one can see the following image:

What is interesting is that Jerusalem is not mentioned in the Koran. It

was in the century after Muhammad’s death, that politics, prompted the

Damascus-based Umayyad dynasty, which controlled Jerusalem, several centuries

before the Ottomans to make this city sacred. Embroiled in fierce competition

with a dissident leader in Mecca, the Umayyad rulers were seeking to diminish

Arabia at Jerusalem’s expense. They sponsored a genre of literature praising

the “virtues of Jerusalem” and circulated re-invented accounts of the prophet’s

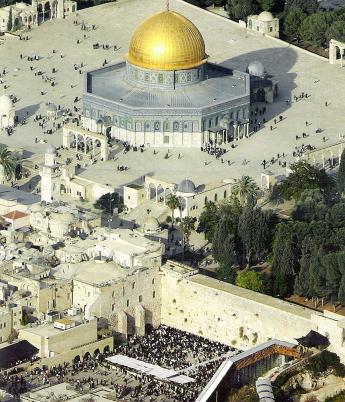

sayings or doings (called hadiths) favorable to Jerusalem. In 688-91, they

built the Dome of the Rock, on top of the remains of the Jewish Temple. They

also were the ones that reinterpreted the Koran to make room for Jerusalem.

However, when the Umayyad dynasty collapsed in 750, Jerusalem fell into

near-obscurity. For the next three and a half centuries, texts praising the

city lost favor, and the construction of glorious buildings not only stopped,

but existing ones unwittingly followed a similar fate as the Jewish Temple (the

Dome over the rock collapsed in 1016).

The inhabitants of what now is called Palestine and Israel, at the start

of the 20th Cent. Considered themselves part of the Ottoman-dominated

Syrian provinces. Arab nationals from Nablus, Jerusalem, and Jaffa considered

themselves Ottomans or Syrians. The idea to call themselves ‘Palestinians’ came

as a reaction to increasing migration by Zionist settlers from Europe, especially

after WWI.

The Hashemite imperial dream

Before the first world war, Hashemite leader Hussein had been detained

in Istanbul under the caliph, Sultan Abdul Hamid II, hastily conferred to him

the title of emir of Mecca and Medina in the Hejaz in order to prevent the

Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) from appointing its own crony.

Having been told Hussein and his sons might turn against the Ottomans,

the British became positively inclined towards the Hashemites and suggested making them rulers of some sort of Arabian

Empire after the war. But in addition to the Hashemites, London was also allied

with the French and with other tribes against the Ottomans, and thus could not

make the Hashemites the unquestioned rulers of all of Arabia (the Peninsula as

well as the Levant). Furthermore, the Saudis in 1900 had launched the

reconquest of Arabia from Kuwait and had gained control over the eastern and

central parts of the peninsula. By the mid-1920s, the Hashemites lost control

over the peninsula to the Saudis, paving the way for the eventual creation of

Saudi Arabia.

Thus the British moved the Hashemites to an area in the northern part of

the peninsula, on the eastern bank of the Jordan River. Centered around the

town of Amman, they named this protectorate carved from Syria “Trans-Jordan,”

as in “the other side of the Jordan River,” since it lacked any other obvious

identity. After the British withdrew in 1948, Trans-Jordan became contemporary

Jordan. The Hashemites also had been given another kingdom, Iraq, in 1921,

which they lost to a coup by Nasserist military officers

in 1958.

West of the Jordan River and south of Mount Hermon was a region that had

been an administrative district of Syria under the Ottomans. It had been called

“Philistia” for the most part, undoubtedly after the Philistines whose Goliath

had fought David thousands of years before. Names here have history. The term Filistine eventually came to be known as Palestine, a name

derived from ancient Greek, and that is what the British named the region,

whose capital was Jerusalem.

Significantly, while the people of this area were referred to as

Palestinians, a demand for a Palestinian state was virtually nonexistent in

1918. The European concept of national identity at this time was still very new

to the Arab region of the Ottoman Empire. There were clear distinctions in the

region, however. Arabs were not Turks. Muslims were not Christians, nor were

the Jews. Within the Arab world, there were religious, triba,l

and regional conflicts. For example, there were tensions between the Hashemites

from the Arabian Peninsula and the Arabs settled in Trans-Jordan, but these

were not defined as tensions between the country of Jordan and the country of

Palestine. They were very old and very real but were not thought of in national

terms.

But it was the Hashemite imperial dream that would be the first to place

the ‘Palestine Question’ on the pan-Arab political agenda as its most

celebrated cause. Already during the revolt against the Ottoman Empire, Faisal

had begun toying with the idea of establishing his Syrian empire, independent

of his father’s prospective regional empire. In late 1917 and early 1918, he

went so far as to negotiate this option with key members of the Ottoman

leadership behind the backs of his father and

his British allies. As his terms were rejected by the Ottomans, Faisal

tried to gain great-power endorsement for his imperial dream by telling the

post-war Paris Peace Conference that ‘Syria claimed her unity and her

independence’, and that it was ‘sufficiently advanced politically to manage her

own internal affairs ’if given adequate foreign and technical assistance.’

European Jews had been moving into this

region under the Ottoman rule since the 1880s, joining relatively small

Jewish communities that had existed there (and in most other Arab regions) for

centuries. The movement was part of the Zionist movement, which, motivated by

European definitions of nationalism, sought to create a Jewish state in the

region. The Jews came in small numbers, settling on land purchased for them by

funds raised by Jews in Europe. Usually, this land was bought from absentee

landlords in Cairo and elsewhere who had gained ownership of the land under the

Ottomans. The landlords sold the land out from under the feet of Arab tenants,

dispossessing them. From the Jewish point of view, this was a legitimate

acquisition of land. From the tenants’ point of view, this was a direct assault

on their livelihood and eviction from land their families had farmed for

generations. And so it began first as real estate transactions, winding up as

partition, dispossession, and conflict after World War II and the massive

influx of Jews after the Holocaust.

Enter Hajj Amin al-Husseini

In order to inflame Muslim opinion during the 1920’s, Arab nationalists

under the leadership of Hajj Amin al-Husseini circulated doctored photographs

of a Jewish flag with the Star of David flying over the Dome of the Rock. Hajj

Amin al-Husseini also instigated a move to change the paved area in front of

the generally recognized to be Jewish-Wailing (Western) Wall, which was

transformed from a cul-de-sac into an open thoroughfare. The British one could

argue helped politicize the issue by the decision to appoint Hajj Amin

al-Husseini as grand mufti of Jerusalem.

The heart of the Palestinian Arab argument at the time was that the

Western Wall was primarily a Muslim holy site. According to Muslim traditions

they claimed, it was where Muhammad tied his winged horse-, on whom he had

miraculously flown from Mecca to Jerusalem before ascending to the heavens from

the Temple Mount (see the wall below):

Husseini then sought to further internationalize his struggle. The

Supreme Muslim Council authorized him to invite Arab and Muslim leaders to a

World Islamic Conference in Jerusalem slated for December 1931. When the

conference opened the attendance initially looked impressive-about 130

delegates from twenty-two countries. Important states were absent, though.

Turkey did not attend and even sought to subvert the conference, concerned that

it would become a forum for restoring the caliphate and undermining the secular

regime of Ataturk. The Saudi leader, King Abdul Aziz ibn Saud, diplomatically

explained that the invitation to the Jerusalem conference had arrived too late.

In all likelihood, a Saudi decision had been taken to boycott the whole event.

(1)

Their approach was colored by their experience in organizing the

Congress of the Islamic World in Mecca back in 1926. That conference had ended

acrimoniously, with its resolution to meet annually in Mecca coming to naught.

Five years later, Ibn Saud was not going to lend his weight to a Jerusalem

conference that might succeed where the Mecca conference had failed. Clearly,

Husseini had not convinced international Muslim leaders that Jews were

threatening Islamic holy sites. In fact, the purpose of the whole event was not

entirely clear. Husseini had stressed to invitees that the conference would

deal with the Buraq al-Sharif. In his public call to the conference, however,

Shawkat Ali said nothing about the Buraq al-Sharif, but rather spoke more

generally about how Muslims might defend their civilization.

Husseini's conference was convened on December 6, 1931, which

corresponded on the Islamic calendar to the day that Muhammad ascended to the

heavens from the Temple Mount. At the opening of the conference, Husseini's

supporters resorted to their tried and true tactic of disseminating doctored

photos, this time showing Jews with machine guns attacking the Dome of the

Rock. The use of this transparent propaganda alienated many delegates, who held

a protest meeting at the King David Hotel presided over by Husseini's

Palestinian rival, Ragheb Bey al-Nashashibi, the Jerusalem mayor. Husseini's

Congress sought to establish a permanent body that would convene every two

years. The executive committee of the congress was headed by Husseini, thus

giving him a pan-Islamic title and platform for the first time.

The congress also announced the need to establish an Islamic university

in Jerusalem, which apparently was not looked on favorably by the religious

leadership at al-Azhar in Egypt. Adopting a resolution proclaiming the sanctity

of the Buraq al-Sharif, the Congress rejected the report of the "Wailing

Wall Commission." Finally, it formally decided to deny Jews access to the

al-Aqsa Mosque, despite the fact that Jews had their own religious reasons for

staying away from the Temple Mount. Notably, during these disputes over the

Western Wall Husseini did not adopt the tactic later embraced by Vasser Arafat

of denying in total the religious history of the Jews. For example, the Supreme

Muslim Council, which Husseini had headed since 1921, published an English-language

book in 1924 for visitors to the Temple Mount area titled A Brief Guide to

al-Haram ai-Sharif Jerusalem. The book's historical sketch of the site related

that "the site is one of the oldest in the world. Its sanctity dates from

the earliest (perhaps from pre-historic) times. Its identity with the site of

Solomon's Temple is beyond dispute." The 1930 edition remained unchanged

despite the 1929 Western Wall riots. The Supreme Muslim Council did not engage

in Temple Denial, as Arafat's generation would decades later. Beginning in

1936, Jerusalem 's position in Palestinian politics was greatly affected by

what became known as the Arab Revolt, although the revolt did not initially

break out in Jerusalem. Husseini and the Arab Higher Committee-another new body

under his leadership-declared a nationwide strike. In July 1937, the British

finally cracked down on the mufti, who hid out on the Temple Mount for three

months. (2)

The area had become a hiding place for weapons and explosives by

Palestinian Arabs. In October 1937, Husseini fled British Palestine, first

heading for Lebanon, then Iraq, and finally Europe, where he met in Berlin with Adolf Hitler during November

1941 and became a close ally of the Nazi cause.

On November 26, 1942, al-Husseini, cast from Berlin a public radio

speech in Arabic in what became a striking example of the translation of Nazi propaganda into the idioms in the Arab

world even today. “Jews and capitalists have

pushed the United States to expand this war, in order to expand their influence

in new and wealthy areas. America is the greatest agent of the Jews, and the

Jews are rulers in America.”

Martin Cüppers and Klaus-Michael Mallmann, in

a book published in 2006 "Halbmond und Hakenkreuz" detailed how when the

Mufti visited Axis capitals and met Adolf Hitler and Heinrich Himmler, a plan

was hatched to wipe out all the Jews that were living in Palestine at the time.

The process of extermination was about to be activated and the SS and SD

officers had been selected and assigned to the effort. They were to operate

behind the lines with the help of those in the region who were eager to join

the task force. Named "warrant for genocide" by Norman Cohn, not

unlike the earlier Nazi propaganda, Hamas

today still refers to the "protocols" as fact.

Jerusalem following November

1947

It was noteworthy that prior to the adoption of the UN General Assembly

resolution in November 1947 calling for the partition of Palestine, the

representatives of the Palestinian Arabs did not make the issue of Jerusalem

their primary focus. Jama al- Husseini, the mufti’s cousin, who presented the

Palestinian Arab position before the United Nations, still used pan-Arab motifs

in making the case of the Arab Higher Committee that he represented: “one

consideration of fundamental importance to the Arab world was that of racial

homogeneity.” He explained that “the Arabs lived in a vast territory stretching

from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean, spoke one language, had the same

history, tradition, and aspirations.” He referred to the threat of an “alien body”

entering the Middle East region. (3)

The rise of Gamal Abdul Nasser

Under the monarchy prior to the rise of Gamal Abdul Nasser in 1952, Egypt was hostile to

Israel’s creation. But when the Egyptian army drove into what is now called

Gaza in 1948, Cairo saw Gaza as an extension of the Sinai Peninsula, as it saw

the Negev Desert. It viewed the region as an extension of Egypt, not as a distinct

state.

Nasser’s position was even more radical. He had a vision of a single,

united Arab republic, both secular and socialist, and thought of Palestine not

as an independent state but as part of this United Arab Republic (which

actually was founded as a federation of Egypt and Syria from 1958 to 1961).

Yasser Arafat was in part a creation of Nasser’s secular socialist championing

of Arab nationalism. The liberation of Palestine from Israel was central to

Arab nationalism, though this did not necessarily imply an independent

Palestinian republic.

Arafat’s role in defining the Palestinians in the mind of Arab countries

also must be understood. Nasser was hostile to the conservative monarchies of

the Arabian Peninsula. He intended to overthrow them, knowing that

incorporating them was essential to a United Arab regime. These regimes in

return saw Arafat, the PLO and the Palestinian movement generally as a direct

threat.

The April 1949 Armistice

Agreement

The true motivation behind Jordanian policy in reference to April 1949

Armistice Agreement was revealed in a frank exchange on February 23, 1951,

between Jordanian prime minister Samir al-‘Rifa’I and

an Israeli envoy, Reuven Shiloah. Al-Rifa’I disclosed

why his country had no intention of implementing its armistice obligations

under Article VIII-Jordan simply had nothing to gain from the armistice any

longer. Jordan no longer needed access to the Bethlehem road from Israel-the

Jordanians had built another road instead-and the Old City would no longer need

Israeli electricity after Jordan worked out a different source of electrical

power. (4)

It would be erroneous to conclude however that during the period of its

rule, Jordan essentially cut itself off from Jerusalem; Jordan always sought to

invest in the area of the Temple Mount. Between 1952 and 1959, the Jordanians

undertook a new restoration project at the Dome of the Rock. The U.S. began to

receive reports in 1960 that Jordan planned to treat Jerusalem as a second

capital. (5)

During the period of Jordanian rule, another political body would come

to influence the struggle for Jerusalem: the Palestine Liberation Organization

(PLO). It was founded in May 1964 by a conference of four hundred delegates

meeting at the Intercontinental Hotel in Jordanian-controlled Jerusalem. Its

first head, Ahmad Shukeiry, was a Palestinian who

served as a Saudi Arabian diplomat until he fell out with the Saudi leadership.

The early PLO was completely controlled by Egypt, which sponsored the proposal for

its creation at an Arab Summit meeting in order to reduce the relative

responsibility of the Arab states to resolve the Palestinian issue. The PLO

covenant rejected Jewish claims to Palestine and the validity of the League of

Nations mandate. But it did not specifically single out Palestinian claims to

Jerusalem, which are not even mentioned in the covenant-either in its original

version promulgated in 1964 or in its 1968 rendition. (6)

The early PLO had good reasons to leave Jerusalem out of its founding

charter. It did not want to antagonize its Jordanian hosts.

The plight of a Palestinian

State and Jerusalem

One of the ironies is that while Palestinian nationalism’s first enemy

is Israel, but if Israel ceased to exist, the question of an independent

Palestinian state would not be settled. All of the countries bordering such a

state would have serious claims on its lands, not to mention a profound

distrust of Palestinian intentions. The end of Israel thus would not guarantee

a Palestinian state. One of the remarkable things about Israel’s Operation Cast

Lead in Gaza was that no Arab state moved quickly to take aggressive steps on

the Gazans’ behalf. Apart from ritual condemnation, weeks into the offensive no

Arab state had done anything significant. This was not accidental: The Arab

states do not view the creation of a Palestinian state as being in their interests.

They do view the destruction of Israel as being in their interests, but since

they do not expect that to come about anytime soon, it is in their interest to

reach some sort of understanding with the Israelis while keeping the

Palestinians contained.

The emergence of a Palestinian state in the context of an Israeli state

also is not something the Arab regimes see as in their interest, and this is

not a new phenomenon. They have never simply acknowledged Palestinian rights

beyond the destruction of Israel. In theory, they have backed the Palestinian

cause, but in practice, they have ranged from indifferent to hostile toward it.

Indeed, the major power that is now attempting to act on behalf of the

Palestinians is Iran, a non-Arab state whose involvement is regarded by the

Arab regimes as one more reason to distrust the Palestinians.

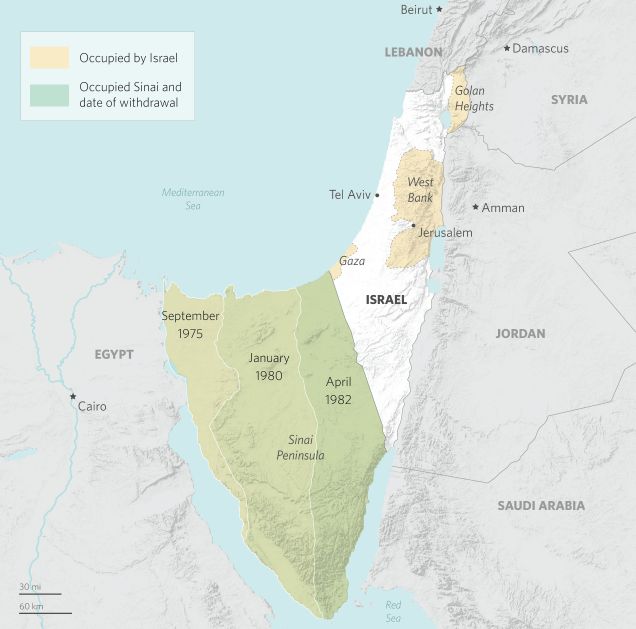

1975-1982: Israel Withdraws From Sinai

In a way, the Palestinians are trapped in four ways. First, they are

trapped by the Israelis. Second, they are trapped by the Arab regimes. Third,

they are trapped by geography, which makes any settlement a preface to

dependency. Finally, they are trapped in the reality in which they exist, which

rotates from the minimally bearable to the unbearable. Their choices are to

give up autonomy and nationalism in favor of economic dependency, or retain

autonomy and nationalism expressed through the only means they have, wars that

they can at best survive, but can never win.

The separation between the two Palestinian regions imposes an inevitable

regionalism on the Palestinian state. Gaza and the West Bank are very different

places. Gaza is about 25 miles long and no more than 7.5 miles at its greatest

width, with a total area of about 146 square miles. According to 2015 figures,

there is an estimated population of 750,000, which means there are 42,600

people per square mile, compared to 83,800 in Mumbai. In other words, Gaza is better thought of as a

city than a region. And like a city, its primary economic activity should be

commerce or manufacturing, but neither is possible given the active hostility

of Israel and Egypt. The West Bank, on the other hand, has a population density

of a little over 600 people per square mile, many living in discrete urban

areas distributed through rural areas.

In other words, the West Bank and Gaza are entirely different universes

with completely different dynamics. Gaza is a compact city incapable of

supporting itself in its current circumstances and overwhelmingly dependent on

outside aid; the West Bank has a much higher degree of self-sufficiency, even

in its current situation. Under the best of circumstances, Gaza will be

entirely dependent on external economic relations. In the worst of

circumstances, it will be entirely dependent on outside aid. The West Bank

would be neither. Were Gaza physically part of the West Bank, it would be the

latter’s largest city, making Palestine a more complex nation-state. As it is,

the dynamic of the two regions is entirely different.

Gaza’s situation is one of pure dependency amid hostility. It has much

less to lose than the West Bank and far less room for maneuver. It also must

tend toward a more uniform response to events. Where the West Bank did not

uniformly participate in the intifada, towns like Hebron were hotbeds of

conflict while Jericho remained relatively peaceful, the sheer compactness of

Gaza forces everyone into the same cauldron. And just as Gaza has no room for

maneuver, neither do individuals. That leaves little nuance in Gaza compared to

the West Bank, and compels a more radical approach than is generated in the

West Bank.

If a Palestinian state were created, it is not clear that the dynamics

of Gaza, the city-state, and the West Bank, more of a nation-state, would be

compatible. Under the best of circumstances, Gaza could not survive at its

current size without a rapid economic evolution that would generate revenue

from trade, banking and other activities common in successful Mediterranean

cities. But these cities have either much smaller populations or much larger

areas supported by surrounding territory. It is not clear how Gaza could get

from where it is to where it would need to be to attain viability.

Therefore, one of the immediate consequences of independence would be a

massive outflow of Gazans to the West Bank. The economic conditions of the West

Bank are better, but a massive inflow of hundreds of thousands of Gazans, for

whom anything is better than what they had in Gaza, would buckle the West Bank

economy. Tensions currently visible between the West Bank under Fatah and Gaza

under Hamas would intensify. The West Bank could not absorb the population flow

from Gaza, but the Gazans could not remain in Gaza except in virtually total

dependence on foreign aid.

The only conceivable solution to the economic issue would be for

Palestinians to seek work en masse in more dynamic

economies. This would mean either emigration or entering the workforce in

Egypt, Jordan, Syria, or Israel. Egypt has its own serious economic troubles,

and Syria and Jordan are both too small to solve this problem, and that is completely

apart from the political issues that would arise after such immigration.

Therefore, the only economy that could employ surplus Palestinian labor is

Israel’s.

Security concerns apart, while the Israeli economy might be able to

metabolize this labor, it would turn an independent Palestinian state into an

Israeli economic dependency. The ability of the Israelis to control labor flows

has always been one means for controlling Palestinian behavior. To move even

more deeply into this relationship would mean an effective annulment of

Palestinian independence. The degree to which Palestine would depend on Israeli

labor markets would turn Palestine into an extension of the Israeli economy.

And the driver of this will not be the West Bank, which might be able to create

a viable economy over time, but Gaza, which cannot.

From this economic analysis flows the logic of Gaza’s Hamas. Accepting a

Palestinian state along lines even approximating the 1948 partition, regardless

of the status of Jerusalem, would not result in an independent Palestinian

state in anything but name. Particularly for Gaza, it would solve nothing.

Thus, the Palestinian desire to destroy Israel flows not only from ideology

and/or religion, but from a rational analysis of what independence within the

current geographical architecture would mean: a divided nation with profoundly

different interests, one part utterly incapable of self-sufficiency, the other

part potentially capable of it, but only if it jettisons responsibility for

Gaza.

The two-state solution

While currently there is still the possibility to have the capital of an

independent Palestine in East Jerusalem, it is difficult to see how Palestine

could survive in a two-state solution. It therefore would have to seek a more

radical outcome, the elimination of Israel, that it cannot possibly achieve by

itself. The Palestinian state is thus an entity that has not fulfilled any of

its imperatives and which does not have a direct line to achieve them. What an

independent Palestinian state would need in order to survive is:

· The recreation of the state of hostilities that existed prior to Camp

David between Egypt and Israel. Until Egypt is strong and hostile to Israel,

there is no hope for the Palestinians.

· The overthrow of the Hashemite government of Jordan, and the movement

of troops hostile to Israel to the Jordan River line.

· A major global power prepared to underwrite the military capabilities

of Egypt and those of whatever eastern power moves into Jordan (Iraq, Iran,

Turkey or a coalition of the foregoing).

· A shift in the correlation of forces between Israel and its immediate

neighbors, which ultimately would result in the collapse of the Israeli state.

Note that what the Palestinians require is in direct opposition to the

interests of Egypt and Jordan and to those of much of the rest of the Arab

world, which would not welcome Iran or Turkey deploying forces in their

heartland. It would also require a global shift that would create a global

power able to challenge the United States and be motivated to arm the new

regimes. In any scenario, however, the success of Palestinian statehood remains

utterly dependent upon outside events somehow working to the Palestinians’

advantage.

Palestinians as a threat to

other Arab states

As we have seen above the Palestinians have been a threat to other Arab

states because the means for achieving their national aspiration require

significant risk-taking by other states. Without that appetite for risk, the

Palestinians are stranded. Therefore, Palestinian policy always has been to try

to manipulate the policies of other Arab states, or failing that, to undermine

and replace those states. This divergence of interest between the Palestinians

and existing Arab states always has been the Achilles’ heel of Palestinian

nationalism. The Palestinians must defeat Israel to have a state, and to

achieve that they must have other Arab states willing to undertake the primary

burden of defeating Israel. This has not been in the interests of other Arab states,

and therefore the Palestinians have persistently worked against them, as we see

again in the case of Egypt.

Paradoxically, while the ultimate enemy of Palestine is Israel, the

immediate enemy is always other Arab countries. For there to be a Palestine,

there must be a sea change not only in the region but in the global power

configuration and in Israel’s strategic strength. For now at least it seems the

Palestinians can neither live with a two-state solution nor achieve the

destruction of Israel.

Abbreviated Timeline of

Israel-Palestine Territory Change and Conflict

As for the reactions so far, Arab countries were quick to launch a war

of words on the American Jerusalem declaration, but there's little room for

them to maneuver diplomatically. The Arabs’ helplessness in view of Trump’s

announcement arises from the circumstances that developed in the Middle East

since the Arab Spring. New coalitions have been formed between Arab states and

the powerful nations; Arab states fight against other Arab states or boycott them. Iran poses a new threat to

them, greater even than the terror organizations. States that once led

diplomatic battles like Egypt, Iraq and Syria can no longer dictate moves,

while the new leader, Saudi Arabia, suffered one

failure after another every time it tried to dictate strategic moves to

sister states.

1) Y. Porath, The Palestinian Arab National Movement: 1929-1939 From

Riots to Rebellion, London, 1977, 10.

2) Meron Benvenisti, City of Stone: The Hidden

History of Jerusalem, Berkley, 1996, 79.

3) Document 4: "UN General Assembly Resolution 181 on the Future

Government of Palestine," Ruth Lapidoth and Moshe Hirsch, eds., The

Jerusalem Question and Its Resolution: Selected Documents, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1994, 13-14.

4) Raphael Israeli, Jerusalem Divided: The Armistice Regime 1947-1967,

London, 2002, 58.

5) Document 31, "Aide Memoire Delivered by the United States

Department of State to the Prime Minister of Jordan Concerning the Intention of

Jordan to Treat the City of Jerusalem as Its Second Capital, 5 April

1960," in Lapidoth and Hirsch, 160.

6) Wasserstein noted that there was no mention of Jerusalem either in

its ten-point political statement issued in Cairo on June 8,1974.

For updates

click homepage here