By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The Ongoing Dilemma of Jammu and

Kashmir

On Nov. 3, at least

11 shoppers were injured in a grenade attack on a flea market in Srinagar, the summer capital

of the Indian union territory of Jammu and Kashmir. One woman later died from

her injuries. It was just the latest terrorist incident since a new government took office in mid-October. In Jammu, the

predominantly Hindu part of the territory, terrorist attacks have killed at

least 44 people this year, including 18 security personnel.

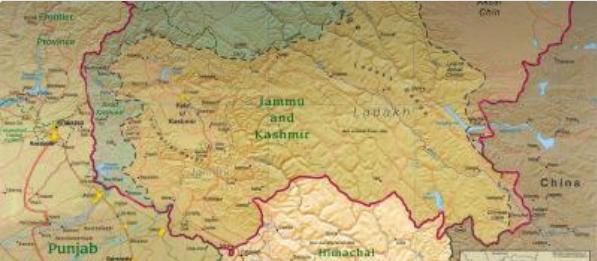

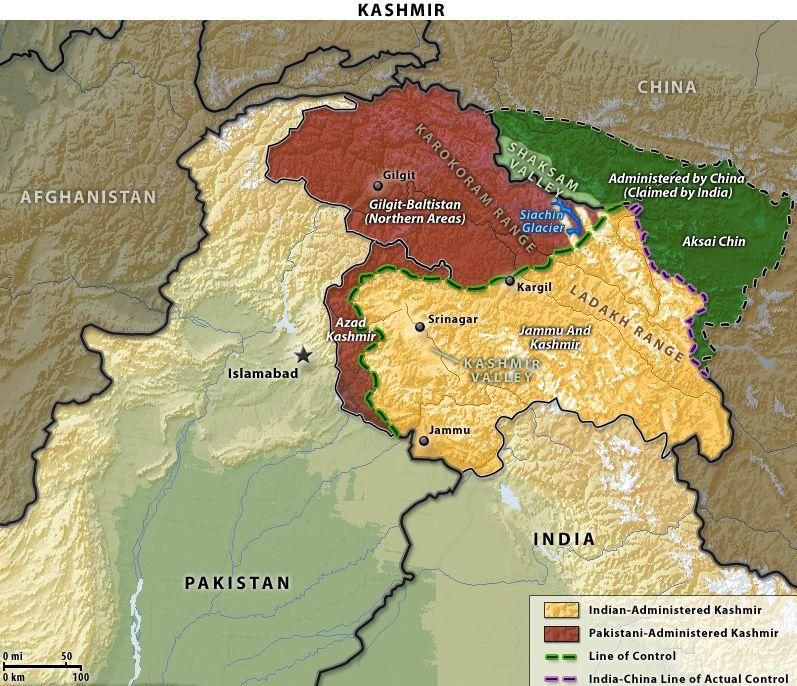

This territorial

conflict over the Kashmir region, primarily between India and Pakistan, and also between China and India in the northeastern portion

of the region. It is a dispute over the region that escalated into three wars

between India and Pakistan and several other armed skirmishes. India controls

approximately 55% of the land area of the region that includes Jammu, the

Kashmir Valley, most of Ladakh, the Siachen Glacier, and 70% of its population;

Pakistan controls approximately 30% of the land area that includes Azad Kashmir

and Gilgit-Baltistan; and China controls the remaining 15% of the land area

that includes the Aksai Chin region, the mostly uninhabited Trans-Karakoram

Tract, and part of the Demchok sector.

It is generally accepted that Kashmir is a victim of

the disputed division of British India during the transfer of colonial power in

1947. A border was created on religious lines, and states with a Muslim

majority formed the newly created Pakistan alongside a predominantly Hindu

India. When India and Pakistan became independent, it was generally assumed

that Jammu and Kashmir, with its 80 percent Muslim population, would accede to

Pakistan, but Kashmir was one of 565 princely states whose rulers had given their

loyalty to Britain but preserved their royal titles. The partition plan, negotiated by the last viceroy, Lord Mountbatten,

excluded these princely states, which were granted independence without the

power to express it.

Initially, the

British created the state of Jammu and Kashmir from a disparate group of

territories shorn from the Sikh kingdom placing it under the rule of a

Dogra raja, and during the late nineteenth century, they directly intervened in

the administration of the state. The consequent land settlement of the region

led to the breakdown of the state monopoly on grain distribution, the emergence

of a class of grain dealers, the creation of a recognizable peasant class, and

the decline of the indigenous landed elite. Additionally, the slump in the

shawl trade beginning in the 1870s meant that shawl traders were in a state of

financial and social decline by the late nineteenth century. At the same time,

the Dogra state became more interventionist, and centralized, and the

"Hindu" idiom of its rule became increasingly apparent.

But contrary to popular belief, it was

not the isolation of the Kashmir Valley that produced narratives of regional

and religious belonging; rather, it was the Valley's links with the world

outside that helped reinforce the poetic discourse on identities in the

mid-eighteenth to early-nineteenth centuries.

Rather, the axiom of Kashmir as the

paradise on earth, which even then belied the reality of the condition of the

Valley and its inhabitants, was coined by the Mughal emperor Jehangir.1

The 1947 Partition created two newly

independent states - India and Pakistan - and triggered perhaps the most

significant movement of people in history, outside war and famine. About 12

million people became refugees. Between half a million and a million people

were killed in religious violence and rhetoric that continues

today.

The partition of

India in August 1947 was, to a degree, related to British concerns about the

possibility the USSR could acquire influence.

The Situation as It Is Today

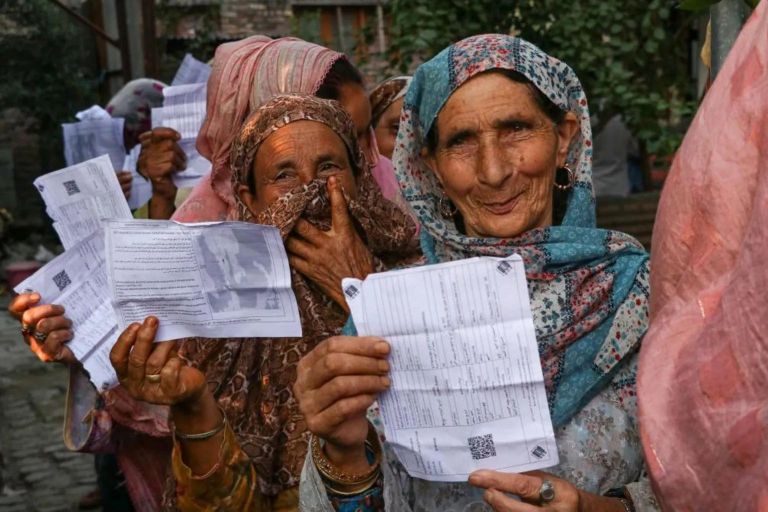

The former state of Jammu and Kashmir -

now divided into two federally administered territories - is holding its first assembly election in a decade. The third and last phase of voting is on Tuesday and

results will be declared on 8 October.

Since the 1990s, an

armed separatist insurgency against Indian rule in the region has claimed

thousands of lives, including those of civilians and security

forces. Earlier, elections were marred by violence and boycotts as

separatists saw polls as a means for Delhi to try and legitimize its control.

The high voter turnout now signals a change - people here say they have waited long to be heard.

“The level of poverty

in our area is severe,” says 52-year-old Mohammad Yusuf Ganai after casting his

vote. He laments that the lack of jobs has forced educated young Kashmiris to

"sit at home". The last elections a decade ago resulted in a

coalition government that collapsed in 2018. Before new polls could be held,

Prime Minister Narendra Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party

(BJP) government revoked the

region's autonomy and

statehood, sparking widespread discontent among Kashmiris.

For five years, Jammu

and Kashmir has been under federal control with no local

representation, and this election offers people a long-awaited chance to voice

their concerns.

“We will finally be

able to go to the elected official with our problems,” says 65-year-old

Mohammad Abdul Dar.

BJP candidate Engineer Aijaz Hussain (centre) says people in Kashmir have faith in the election

process now

One argument offered

by Indian security officials holds that the powerful Pakistani security

establishment, which has never reconciled itself to Indian rule in any part of

Kashmir, has ramped up its support for

terrorist actions.

Islamabad may seek to convey a message that it can undermine newly elected

Jammu and Kashmir Chief Minister Omar Abdullah. He is the vice president of the

regional National Conference, the party with the longest lineage in Kashmir,

and the scion of a noted Kashmiri political

family.

Pakistan—and

particularly its security apparatus, which has long controlled policies on the

Kashmir question—has been smarting since Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi

and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) revoked Article

370. Removing the region’s special autonomous status made good on a

long-standing electoral promise and turned Jammu and Kashmir into a union

territory, bringing it mostly

under the control of the national government.

The BJP hoped that

this would not only undermine Pakistan’s claim to Kashmir but also end

simmering secessionist sentiment in the region as citizens reconciled

themselves to the new status quo. Pakistan vigorously protested the 2019

decision, including at the United Nations, to little avail. Five years later, with an elected

government now in place in Jammu and Kashmir, Islamabad’s security

establishment may have decided that now was the moment to sow discord in the

region once again.

However, some

analysts attribute the resurgence of terrorist violence in Kashmir

to a different source, arguing that the recent uptick may be locally

organized rather than

inspired and abetted by foreign forces. In this view, policies in the territory

after the revocation of Article 370 contributed to popular discontent and

spawned indigenous militancy; the quashing of dissent has fueled resentment

against the high-handed tactics of the Indian state.

BJP candidate Engineer Aijaz Hussain (centre) says people in Kashmir have faith in the election

process now

The BJP government

insists that scrapping the region’s special status and placing it under direct

rule has brought peace and development, with Prime Minister Modi announcing

$700m (£523m) in projects during a visit in March. It’s now up to BJP candidate

Engineer Aijaz Hussain in Srinagar's Lal Chowk to convince voters of this

message.

“Previously, no one

would go door to door [to campaign]. Today, they are. This is our achievement,

isn’t it?” says Aijaz. He points to the increased voter turnout as proof

of faith in the election process, with the recent parliamentary elections seeing

record participation. Yet, despite these claims, the BJP did not contest those

elections and is now only fielding candidates in 19 of the 47 assembly seats in

the Kashmir valley.

The party’s

stronghold remains the Hindu-dominated Jammu region with 43 seats, where it is

hoping to score well. “Our organisation is weak

in other constituencies,” admits Aijaz.

The Hindu nationalist

BJP has been trying to make inroads in the Muslim-majority Kashmir valley,

where it has had little presence.

The Current Violence

A third explanation

attributes the recent spike in terrorist violence to Indian troop

redeployments. The Modi government has moved a substantial number of soldiers

from the Kashmir Valley—the principal locus of terrorist activity in the

region—to the Himalayan front, where India has been engaged in a standoff with China on the countries’ disputed border

since a deadly clash in 2020. The specific number of troops who have been moved

remains classified.

Of course, these

three factors could be at play in Indian-administered Kashmir. Pakistan’s

security and intelligence services may have returned to their support for

terrorism in the region as a new

state-level government was

about to assume office. The inability of this government, which has not been

granted police powers, to contain an upsurge in terrorist activity could

hobble its ability to rule effectively. This could lead to losing popular support

and contribute to political disenchantment and alienation.

Simultaneously, the

administration in Kashmir before this year’s election added to the frustrations

of Kashmiris, especially in the Kashmir Valley, cannot be dismissed. Despite

the Modi government’s trumpeting promises of economic development in the

region, little of it

has occurred.

(Furthermore, a rise in terrorist attacks will certainly challenge this

narrative.) Among other matters, unemployment

remains high,

contributing to Kashmiri youth discontent.

The unhappiness of

Kashmir Valley residents was palpable in the aftermath of the abrogation of Article 370. An Indian

Supreme Court judgment last December to uphold the 2019 decision did little to

assuage Kashmiri Muslims and heightened

fears about an

erosion of their rights. In August, reputed analyst Radha Kumar told the Diplomat that a sense of

“alienation” from the Indian state had deepened in the region since 2019. For

the most part, this year’s election at least gave Kashmiris an outlet to

express their political sentiments; they now have high expectations of

their new government.

Asserting an

unequivocal causal link between the disenchantment of Muslim Kashmiris and the

return of terrorist activity to the region may be difficult. However, this

sense of hopelessness among a significant segment of Kashmir’s population may

have contributed to the return of extremist violence.

While regional

political parties promise change and say they are fighting for the rights of

Kashmiris, how much influence will they have after these elections? Lawyer

Zafar Shah anticipates friction between the federal administration and the

elected government which will soon assume charge.

Before 2019, when

Jammu and Kashmir was a state, the chief minister

could enact laws with the consent of the governor, who was bound by the state

cabinet’s recommendations.

Now, as a federal

territory under a Lieutenant Governor (LG), the chief minister must get the

LG's approval, especially on sensitive issues like public order, appointments

and prosecutions. Power has shifted, says Mr Shah, as

the LG won’t act without clearance from the federal home ministry.

“Whether the LG can

create hurdles in the government’s working, that’s a matter to be seen when an

actual situation arises,” adds Mr Shah. Despite the

challenges, many in Kashmir hope these elections will give them a chance to

finally have their own representatives to voice their concerns.

1. See also G.M.D.

Sufi, Kashir: Being a History of Kashmir From

Earliest Times to Our Own. 2 vols. New Delhi, 1974, vol. i, p. 295.)

For updates click hompage here