By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The Forever War in Gaza

Less than two months

after he committed to a phased cease-fire with Hamas, Israeli Prime Minister

Benjamin Netanyahu resumed his country’s war in the Gaza Strip. On March 18,

Israeli air force jets attacked military sites, killing more than 400

Palestinians, including over 300 women and children, according to Gaza’s

Hamas-controlled Ministry of Health—a devastating toll even by the war’s

earlier standards. The short-lived truce allowed for the release of 30 hostages

Hamas took during its shock attack on Israel on October

7, 2023, as well as the repatriation of eight deceased captives. Last week,

the Israeli government proposed resuming a cease-fire in exchange for the

return of 11 more hostages and 16 more bodies.

However even if Hamas and Israel hammer out a new, short-term

agreement to halt hostilities, Gaza is unlikely to see real peace any time

soon. Since the horrific October 7 massacre, which claimed the lives of around

1,250 Israelis, Netanyahu has pursued two goals with his military operations in

the strip—free all the hostages and destroy Hamas. But these goals cannot be

achieved at the same time: Hamas refuses to subscribe to a peace process that

involves its own annihilation, and as long as Israel

is committed to that outcome, Hamas’s surviving leaders have a powerful

incentive to hold on to hostages to deter Israeli attacks that might kill them.

This means that even

if a cease-fire resumes, Hamas is likely to delay releasing every

last hostage, Israel is likely to find ways to avoid proceeding through

phases that allow Hamas to retain power, and any deal may again fall apart at

its final stages. Netanyahu increasingly believes that ordering military action

pays off. Projecting strength, after all, weakened Iran and hobbled its

Lebanese proxy militia, Hezbollah. And whereas former U.S. President Joe

Biden’s team tried to contain Israeli escalations, Netanyahu has a more

permissive ally in President Donald Trump. In a sign of the two leaders’

intimacy—and the importance, for Netanyahu, of keeping Trump on side—the

Israeli prime minister rushed to Washington on Sunday to see Trump for the

second time in three months. Feeling emboldened, the Israeli military has also

proposed a far-reaching plan to reoccupy Gaza, and Netanyahu’s ultra-right-wing

partners are more brazenly advancing a proposal to expel most of Gaza’s

inhabitants.

It remains somewhat

unclear, however, whether Netanyahu is prepared to implement his political

partners’ biggest dreams. He has to consider Trump’s

position, changeable as it is, and whether Israel’s military is capable of

embarking on a costly, long-term operation in Gaza. For the time being, his

best option is probably to pursue a middle path that keeps his options open and

maintains his allies’ belief that he is on their side—and that middle path involves continued operations in Gaza.

Confidence Game

When Israel went to

war in Gaza 18 months ago, there was almost unanimous agreement among Israelis

that Hamas must be eliminated. But it soon became clear that Israel’s two

military objectives—secure the release of the hostages and destroy Hamas—could

not be accomplished in the same time frame. Even assuming that it is possible

to eradicate Hamas, a terrorist guerrilla organization that still commands

substantial grassroots support in Gaza, doing so would take years. The Israeli

hostages, however, do not have that kind of time. According to an analysis

by The New York Times, between October 2023 and early March 2025, 41

hostages died in captivity. Some died from starvation, disease, and murder, and

others perished accidentally as a result of Israeli

military operations. Those hostages who have returned to Israel from Gaza in

recent months described being held in extremely harsh conditions: many were

kept chained in tunnels with little food and no medical care and some reported

experiencing torture.

Because Israel did

not clearly prioritize one goal over the other, it has yet to achieve either

one. Since the war began, Israel has killed most of Hamas’s top leaders,

including the group’s Gaza chief, Yahya Sinwar. But the organization still has

a governance structure, and to discourage Israeli attempts to assassinate them,

its remaining leaders seek to maintain a human shield—a kind of insurance

policy—in the form of a small number of hostages, mostly soldiers. Such an

arrangement is unacceptable to Netanyahu. For him, only two options are on the

table: Hamas’s total surrender and the expulsion of its leadership from Gaza,

or the continuation of the war until the Israeli military achieves that same

outcome. In the second scenario, he would likely blame Hamas for the deaths of

additional hostages.

Any hope that the

United States would push Israel to stick to a lasting cease-fire faded with

Trump’s inauguration. Although Trump did pressure Netanyahu to agree to the

January cease-fire, since then, his administration’s approach has become more

muddled. Every few days, the American team presents new proposals, but the

discussions remain deadlocked; Trump now toggles between disinterest in the

conflict and fantastical ideas, such as his proposition in February that the

United States could take ownership of Gaza

and turn it into a tourist “Riviera.”

The Trump

administration has not really faced or sought to resolve the fundamental

contradiction delaying serious peace talks: Netanyahu insists that any

cease-fire process must end in the dismantling of Hamas. But this a redline

that Hamas is unwilling to cross, although it reportedly may consider

abdicating its political power while maintaining its military strength, a kind

of compromise being tested in Lebanon with Hezbollah’s consent. Neither the

Americans nor the Arab mediators from Egypt and Qatar, however, have so far

managed to persuade Hamas’s leaders to sign an agreement that would end their

ultimate political mission: to take control of the Palestinian struggle against

Israel.

Other developments

have made it less urgent for Netanyahu to seek a settlement. By now, Israel’s

military has partially recovered from the shock of October 7. Hamas’s abilities

to organize another large-scale attack or launch significant rocket barrages into

Israeli territory have been degraded. On other fronts, Israel now holds the

upper hand. Last November, Hezbollah was forced to agree to a humiliating

cease-fire, and although the Israeli air force continues to strike the group’s

targets in southern Lebanon (and, last week, in Beirut), the battered

organization has yet to respond. Israel’s exchanges of fire with Iran last

October were an embarrassment for Tehran. And following the collapse of Bashar

al-Assad’s regime in December, Israel took control of parts of southern Syria.

On the back of these wins, Netanyahu seems emboldened, responding with military

force to enemy provocations he would previously have preferred to contain or

ignore. In mid-March, for instance, after six rockets landed in its territory,

Israel bombed a Hezbollah drone warehouse in southern Beirut, even though it

remains unclear who launched the rockets.

Although the Biden

administration stood by Israel after October 7 and helped prevent further

regional escalation, it also sought to contain Israeli military actions. For

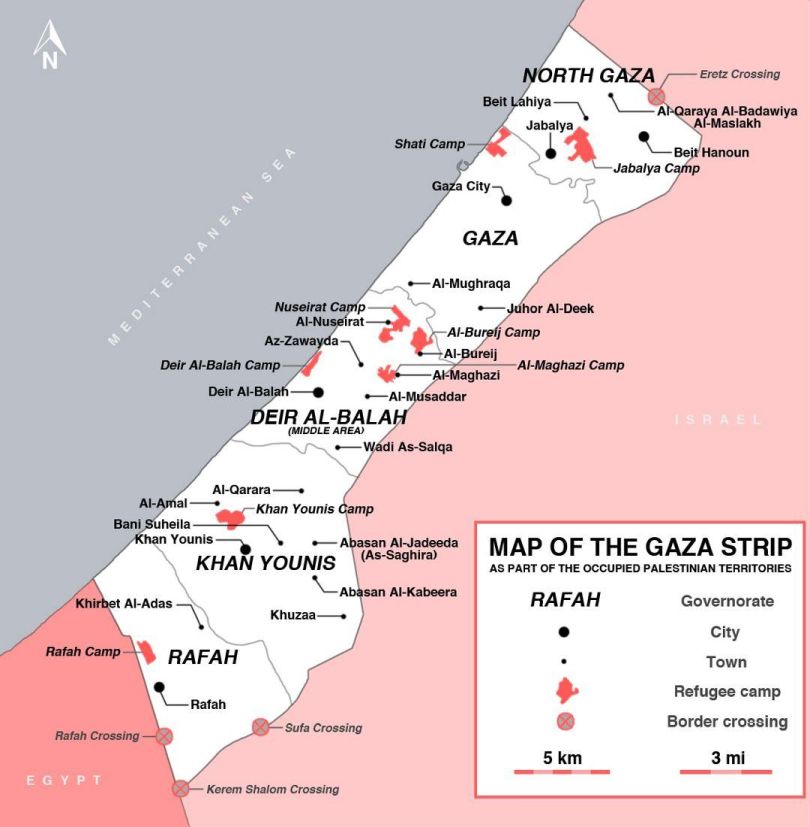

instance, after the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) invaded the southern Gazan city

of Rafah last May—an act Biden’s team had cautioned against—Biden delayed

sending heavy precision munitions and bulldozers to Israel. Trump’s accession

to the White House has removed this counterbalance. Publicly, at least, Trump

supports all of Israel’s actions. And more broadly, the way that he flirts with

ideas such as absorbing Canada and annexing Greenland legitimizes the notion

that strong countries can simply seize territory from their neighbors. When

Netanyahu visited Trump in Washington in February, the U.S. president wondered

aloud why Israel did not take advantage of Assad’s ouster to claim even more

Syrian land. Netanyahu subsequently discussed such an idea with his cabinet,

although it has not gained traction.

Hidden Fissures

Israel appears to be

in a commanding position. Indeed, in mid-March, the military presented an

ambitious plan to the government to redeploy several divisions into Gaza,

conduct a new reserve mobilization, evict northern Gazans back to a shelter

zone in the south, and complete a military occupation of the entire strip—all

in the space of a few months. The IDF’s former chief of staff, Herzi Halevi,

had fiercely opposed the creation of any Israeli military government in Gaza.

But he resigned in early March. His successor, Eyal Zamir—who enjoys warmer

relations with Israel’s political leaders and thus more freedom to pursue his

plans—has indicated he is open to governing the strip.

The Trump

administration may have ceased talking about a plan to clear Gaza of its

inhabitants, but right-wing Israeli politicians have taken up the cause,

interpreting Trump’s proposal as a permission slip to more openly discuss

encouraging Gazans to emigrate voluntarily. In practice, any such “voluntary

emigration” project would involve the use of significant military force to

persuade residents to leave. Israeli Defense Minister Israel Katz, who is

essentially Netanyahu’s puppet, has established a new administrative body in

his ministry to promote emigration.

But deeper weaknesses

and domestic tensions constrain the Israeli government. Despite the blows it

has suffered, Hamas remains far from defeated. Two surviving

military commanders, Izz al-Din al-Haddad and Mohammed Sinwar (Yahya Sinwar’s

brother), are leading its efforts to recover. The multiweek cease-fire

that began in January, which facilitated the delivery of more humanitarian aid

into Gaza, also allowed Hamas to replenish funds by seizing some of that aid

and selling it to Gazan civilians for profit. Israel has estimated that, in

recent months, Hamas has recruited about 20,000 new fighters, and the group’s

leaders are moving to suppress protests against its

rule in northern Gaza. Hamas is repurposing Israeli bombs that failed to

detonate to booby-trap buildings and roads in preparation for another Israeli

invasion.

Reoccupying Gaza

would result in additional military casualties and, quite possibly, the deaths

of more hostages. According to myriad public opinion polls, about 70 percent of

Israelis support a deal with Hamas to release all the remaining hostages, even

if it comes with very high costs, such as ending Israel’s military operations

in Gaza and releasing thousands of Palestinian prisoners from Israeli jails.

But it is not certain whether this public sentiment will translate to the kind

of protest that could constrain Netanyahu’s options. Many Israelis still find

it extremely hard to demonstrate against their government while Israeli

soldiers are fighting and dying in Gaza.

But implementing

either the military plan to occupy Gaza or the “voluntary emigration”

project will carry serious political risk. Tens of thousands of military

reservists have already served hundreds of days each during the war, which has

taken a heavy toll on their careers and families. Israel has, in fact, never

faced so much ambivalence about military service on the part of its

reservists—not even during its politically controversial 1982 war in Lebanon or

during the second intifada, which lasted from 2000 to 2006. Some are

threatening to refuse a call-up because they fear that a sweeping new military

campaign could result in the deaths of more hostages. According to several IDF

commanders I spoke with, many more are considering evading service to remain

with their families. Some reservists’ anger relates to the government’s conduct

outside Gaza, such as its efforts to preserve the ultra-Orthodox exemption from

mandatory military service. But mainly, Israel’s reservists are exhausted and burned out.

So, Netanyahu must

keep performing a delicate balancing act. From his perspective, he must delay

the implementation of any cease-fire that would end the war and foreclose the

fantasy of restoring Israeli settlements in Gaza to satisfy his right-wing

allies. But he cannot sound as decisive as these allies do on fully reoccupying

Gaza and resettling Israelis there. So far, he has been fairly

successful: the Israeli parliament’s passage, in late March, of a budget

bill staved off the threat that his coalition could collapse, forcing an early

election. But one recent cabinet meeting revealed how challenging it is to

maintain this balance. After Netanyahu had commented that the government was

considering various ideas for Gaza’s future, including transferring control to

a consortium of Arab states, the far-right minister for settlements, Orit

Strook, was outraged. “But Gaza is ours, part of the land of Israel,” she

exclaimed. “Are you going to give it to the Arabs?” The prime minister evaded

the question. “Maybe military governance—there are all kinds of options,” he

replied.

The Israeli prime

minister must not only maneuver between a public that demands the release of

the remaining hostages and his political partners’ visions of grandeur. He must

also deal with Trump’s instinct to pursue glory. The U.S. president may still be

seeking his own grand plan: a U.S.-Saudi megadeal that includes the

normalization of diplomatic ties between Israel and Saudi Arabia as well as an

end to the war in Gaza. Netanyahu is now facing a new scandal after two of his

media advisers were arrested and questioned about money they may have illicitly

accepted from the Qatari government. The Israeli prime minister, however,

is nothing if not resilient. He intends to retain his job by any means

necessary. Keeping the Gaza war simmering is the simplest way to do that, no

matter the long-term cost to the hostages, the Palestinians, the Middle East,

and Israel itself.

For updates click hompage here