By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

Explaining The NATO Strategic Concept

Meeting at the Madrid

summit in June, NATO leaders issued their first new “strategic

concept” in a decade. As

expected, Russia took center stage in the document, and the heads of state

declared Moscow a manifest threat to the transatlantic alliance. In a joint

statement, they pledged their commitment to Ukraine “for as long as it takes”

and committed to spending more on defense.

Russia, however, was

not the only major threat identified in the new strategy. For the first time,

the allies said China posed “systemic challenges’’ to “Euro-Atlantic security”

and that its ambitions and policies challenge the alliance’s “interests,

security, and values.” To drive the point home, leaders from Australia, Japan,

New Zealand, and South Korea were on hand to demonstrate unity and

resolve.

NATO’s new focus

is just one of many indications that a new strategic era has begun. For

instance, the Biden administration’s national security strategy states

that “the most pressing strategic challenge” is from “powers that layer

authoritarian governance with a revisionist foreign policy.” The new U.S.

strategy, released in October, labels Russia “an immediate threat to the free

and open international system” and China as the only competitor

with the intent and power to reshape that system. Today Washington has chosen,

perhaps by default, to compete with—and, if necessary, confront—both Russia and

China simultaneously and indefinitely.

This new geopolitical

reality is only beginning to register among policymakers and experts. As the

strategist Andrew Krepinevich has observed, at no time in the past 100 years

has the United States faced a single great-power competitor with a Gross

domestic product (GDP) equal to or greater than 40 percent of the

U.S. GDP? Yet today, the Chinese economy amounts to at least 70 percent of

the U.S. GDP, a figure likely to grow. Each is a nuclear-armed state able to

project political, economic, and military power on a global scale. China and

Russia are also working together. Although there are limits to Russia and

China’s “no limits” quasi-alliance, each appears bent on revising what they

consider a Western-dominated global order.

In 1880, the Prussian

leader Otto von Bismarck contended that “as long as the world is governed by

the unstable equilibrium of five great powers,” Germany should try to be one of three. Among today’s three great powers,

two are far closer to each other than to the United States. There is little

prospect of any near-term change in this basic strategic equation. As a result,

how Washington could operate in a world with two great-power antagonists is the

central question in U.S. foreign policy. Competing with China and Russia on

every issue, and in every place they are active, is a recipe for failure. It is

also unnecessary. A foreign policy that manages these twin challenges requires

setting priorities and making difficult tradeoffs across regions and issues.

That will be far easier said than done.

The Friend Of My Enemy

This was not the

situation that U.S. President Joe Biden thought he would encounter

when he took office. During his initial months as president, administration

officials repeatedly called for a “stable and predictable” relationship with

Russia. Moscow would abjure bad international behavior and allow Washington to

focus more on the China challenge. Others had more ambitious visions. As

recently as February, before Russia’s invasion, several foreign policy

experts counseled a dramatic move on the strategic chessboard.

Just as in the early 1970s when the Nixon administration opened to China to

realign the balance of power with the Soviet Union, the thinking went, now the

United States could align with Russia to offset China. Such a “reverse

Kissinger” would capitalize on traditional rivalries between China and Russia

and Moscow’s apparent desire to engage with Washington as an equal. The United

States would set aside its longstanding concerns about Russia’s domestic and

international behavior to jointly confront the more significant challenge in

Asia.

Such a grand

strategic move, unrealistic before Russia’s invasion, is now unthinkable. Given

Russia’s war of conquest, its disregard for the most basic rules of

international conduct, and its stated desire to upend the European security

order, there will be no rearranging of the chessboard. For the foreseeable

future, Russia will represent a significant threat to U.S. interests and

ideals. Although the war in Ukraine is already depleting Russia’s conventional

military might, Moscow retains the world’s largest nuclear arsenal and a range

of unconventional capabilities that, together with the remaining military and

intelligence tools at its disposal, will allow it to menace neighbors,

interfere in democracies, and violate international rules. Absent a significant

change in its political system, dealing with Russia—even if it is in

decline—will require substantial U.S. attention and resources for years to

come.

In the face of these

Russian depredations, a few experts have offered the opposite suggestion: a

kind of “repeat Kissinger.” With Moscow upending the rules-based order vital to

the peaceful functioning of international politics, perhaps Washington could

find accommodation with China instead. Like Nixon, the United States would

align with China against a violent and risk-tolerant Russia. Fareed Zakaria, Zachary Karabell, and others have posited this approach, which appears

unworkable as some new U.S.-Russia alliance. Acquiescing to Chinese demands—for

the practical domination of Asia, an end to the promotion of democracy and

human rights, a reduced U.S. presence across the Indo-Pacific, and control of

Taiwan and the South China Sea—is a price no American leader will be willing to

pay to balance Russia.

The third group of

U.S. foreign policy experts focuses exclusively on China rather than

Russia. They argue that the United States cannot spread its resources and

attention across Europe and the Indo-Pacific due to Chinese power and

ambitions. Ukraine has emerged as a costly distraction from graver threats

farther east, those experts suggest, and Washington could leave primary

responsibility for managing Russian threats to the Europeans themselves. Yet

the outcome of Russian aggression in Europe will be felt in Asia, and Moscow’s

success or failure in Ukraine stands to encourage or inhibit Chinese designs

elsewhere. That is a primary reason why countries such as Australia, Japan, New

Zealand, Singapore, and South Korea have joined sanctions against Russia and

are assisting Ukraine. And despite longstanding hopes that Europeans will

handle security on their continent absent a significant U.S. role, history

suggests that they will not.

In this new

era, Russia and China represent neither chess pieces to be

moved through assiduous acts of wise statesmanship nor great-power challengers

that can be handled effectively without American activism. They are enduring

and differentiated challenges that must be managed simultaneously. This is the

crux of the United States’ strategic conundrum.

Friends, Money, And Time

The solution proposed

most often is to work with allies and partners. China and Russia’s economic

weight and military strength are formidable, but the combined might of the

United States and its allies is greater still. The U.S. alliance structure,

augmented by new and non-allied partners, represents a major advantage for

Washington. Russia has Belarus, and China has North Korea, the United States

has NATO, five Pacific allies, the G7, and more. If there are sides in these

contests, the world’s most powerful democracies are on the American one. A key

to the success of this strategy is not only to work with partners but also to

acquire new ones and make the ties among them stronger; hence Sweden and

Finland’s joining NATO, the defense technology-sharing arrangement comprising

Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, known

as AUKUS; and the ascent of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, a grouping

that includes Australia, India, Japan, and the United States.

The other truism is

that the United States must augment its sources of strength in this new era of

competition. This is happening now, although the scale and pace are subjects of

much debate. The Biden administration proposed a record (in unadjusted terms)

of $773 billion in defense spending for 2023, which Congress quickly increased.

The CHIPS and Science Act, signed into law in August, allocates more

than $50 billion for domestic semiconductor manufacturing and

promotes the development of advanced technologies. The need to compete with China

has stimulated other moves, such as the creation in 2019 of the

Development Finance Corporation, which invests in development projects in low-

and middle-income countries. Meanwhile, Russian threats have prompted steps to

better secure U.S. election infrastructure and strengthen the defense

industrial base. A more potent, better-defended United States will be better

positioned to deal with the twin challenges of China and Russia.

A third solution

would be to take advantage of temporal asymmetries in the China and Russia

competitions. Beijing employs economic coercion and diplomatic pressure but has

yet to exercise its military option fully; Russia is using nearly all

instruments of national power to conquer Ukraine. This suggests that a

significant effort to punish Russian transgressions now could render that

country weaker, poorer, and far less militarily capable in the future—precisely

when Beijing may wish to match its growing strength with overt aggression. Here

the imperative would be to focus a great deal of energy and resources on the

Russian threat in its current acute phase while resolving to devote the lion’s

share of both to China over the long run.

The exhortations to

strengthen alliances, build domestic strength, and take advantage of time are

all correct. Yet by doing all this, the United States will still be unable to

counter Chinese and Russian influence everywhere, and on every issue,

indefinitely. Nor should it try. Crucial to managing these problems over time

is setting priorities and making difficult tradeoffs across regions and issues.

Berlin Or Laos?

Priority-setting is

one of the most straightforward actions to invoke and one of the hardest things

to do. Even if a rough consensus is possible about which areas and issues

matter most and could become the focus of U.S. activity, the necessary

corollary is that other domains matter far less. It could receive little to no

attention and resources. Assessed individually, every region—the Western

Hemisphere, Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and the global South—has a priority

claim. Many issues have constituencies inside or outside government that argue

for their importance.

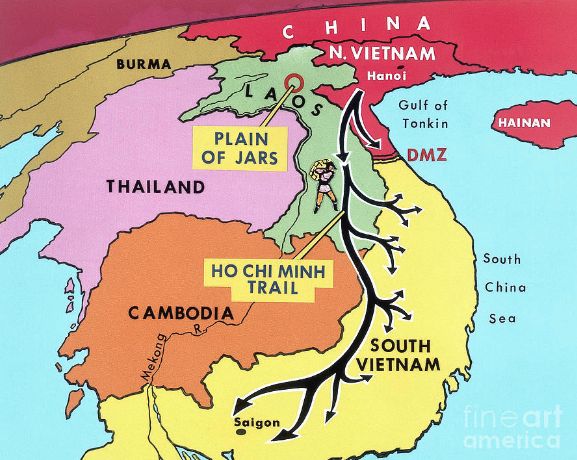

Here, a Cold War lesson

may be instructive. From that era’s early years, the United States resolved to

defend Berlin against Soviet threats, even at the cost of outright war. The

attention, military resources, and energy spent there far exceeded that in

other cities worldwide. Pledging to defend Berlin today looks wise. Twice

during the first half of the twentieth century, the United States crossed the

Atlantic to end wars that began in Europe. By deterring the outbreak of another

during the Cold War period, the United States helped ensure decades of European

peace and prosperity. During that era, however, Washington became so intensely

invested in shaping the domestic politics of Laos that it became the most

heavily bombed nation per capita in history. The U.S. military campaign there

lasted 14 years and failed. Even factoring in the Vietnam War and the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a military supply route for

the North Vietnamese that crossed into Laos, the more than 500,000 bombing

missions the United States conducted over that tiny country appears today, at a

minimum, to have been a significant misallocation of national security

resources.

Historical analogies

are always fraught, and these two are rougher than most. Yet the

difference between Berlin and Laos during the Cold

War suggests a present-day heuristic: Amid indefinite competition with

Russia and China, what issues and regions are more like Berlin, and which are

more like Laos? Which merit the significant investment of U.S. resources and

attention—to resist the expansion of Russian and Chinese influence, for

example, or to establish a new relationship that would strengthen the American

position—and which do not?

Latter-day Berlins

are easier to identify. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine violates the cardinal rule

against the forcible theft of foreign territory and shakes a vital foundation

of the rules-based order. The United States has a strong interest in ensuring

that such a transgression is not only punished but rendered unsuccessful, not

least so that the next would-be aggressor is discouraged from pursuing a

similar course. Chinese activity in the South China Sea threatens the maritime

rules that allow for vital commercial operations and could represent a key area

of focus for U.S. policy. Protecting American democratic practice against

malign interference by Moscow or Beijing is critical to the functioning of the

U.S. political system.

Deprioritizing issues

and areas are more complex. For example, Russia’s military presence in

Venezuela and the Sahel is certainly undesirable. Still, it does not pose the

same threat to existing international rules as the Kremlin’s aggression in

Ukraine. Washington wishes no country to employ Huawei infrastructure for its

5G network. Still, U.S. efforts could be focused squarely on dissuading allies

and close partners from doing so rather than trying to stop everyone from using

it. China’s Belt and Road Initiative poses potential debt-trap dilemmas

for all recipients. Still, the United States could contest its expansion in

Southeast Asia (where increased Chinese influence could lead to naval bases

that could impede U.S. interests) to a much greater degree than in Central Asia

(where the United States’ ability to operate will not be affected).

Similarly, Washington

could focus more on blocking the creation of a Chinese naval facility in the

South Pacific than in West Africa, as Beijing seeks bases in both regions since

the downside costs of Chinese military influence are substantially higher in

the Indo-Pacific than elsewhere. It could not emphasize enlisting China to

solve the North Korean nuclear issue, which can be managed but not solved on

any reasonable timeline. And the United States could take care to absorb the

costs of diversifying away from Chinese-supplied goods only when it makes

national security sense to do so, as with critical technologies, medical

equipment, and rare earth; the majority of American imports from China need not

be re-shored or even friend-shored.

A More Useful Debate

Actions by Moscow or Beijing that would contest key

principles of international order, constrict the United States’ freedom to act,

or undermine the domestic functioning of foreign countries could broadly define

what’s most important. More specifically, policymakers could focus most on

actions in the places and on the issues where the potential damage to vital

U.S. interests is extensive and the potential utility to the challenger is

significant. The large remainder of Russian and Chinese activities worldwide

that are undesirable, offensive, and even contrary to U.S. interests could be

relegated to a lower priority tier. These would receive a significantly smaller

share of American national security resources and attention.

This necessary

prioritization task would move beyond the broad strokes that have characterized

recent U.S. foreign policy. Frequently heard observations—that great-power

competition has returned, that the Indo-Pacific has emerged as a region of

vital importance, or that a revanchist Russia and a determined China have

global ambitions—are of limited utility. What’s needed today is a far more

subtle prioritization of regions and issues and a policy process that considers

the relative importance of multiple crises and opportunities rather than

evaluating each on its own. This is true not only for the executive branch but

also Congress, which tends to focus on headline issues and direct funding and

policy changes accordingly.

In this new era, the

alternative would require the United States to resist undesirable Chinese and

Russian influence wherever it exists—in every region of the world and across a

broad spectrum of issues. To attempt this, the courts fail even while working

with allies and taking every other prudent step to augment American power.

Trying to do it all, everywhere, will produce exhaustion and undermine the U.S.

capacity to address what matters most.

This new strategic

era spurs a dire need among policymakers to ruthlessly prioritize and identify

which issues and regions the United States will ignore, try to mitigate or

assign a small fraction of its considerable attention and resources. Against

its instincts and intentions, the United States has backed its way into

simultaneous contests against two significant powers that define their

interests globally. The United States must pick its battles carefully if it

wants to succeed.

For updates click hompage here