By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

In The Decline of

Magic: Britain in the Enlightenment (2020) Michael Hunter wrote that change

came about gradually, ‘through a kind of cultural osmosis’, dependent as much

on long-available ideas of classical antiquity as on any apparent breakthroughs

in knowledge. And ads that ‘the Enlightenment did not reject magic for good

reasons but for bad ones’.

In fact, a growing

amount of historical scholarship today argues that magical beliefs and

practices had an important influence on the development of natural philosophy

and that around the beginning of the eighteenth century the educated classes

chose to retain some elements of magical systems while rejecting others.

As Michael

Hunter details magical and occult philosophies had long been central to

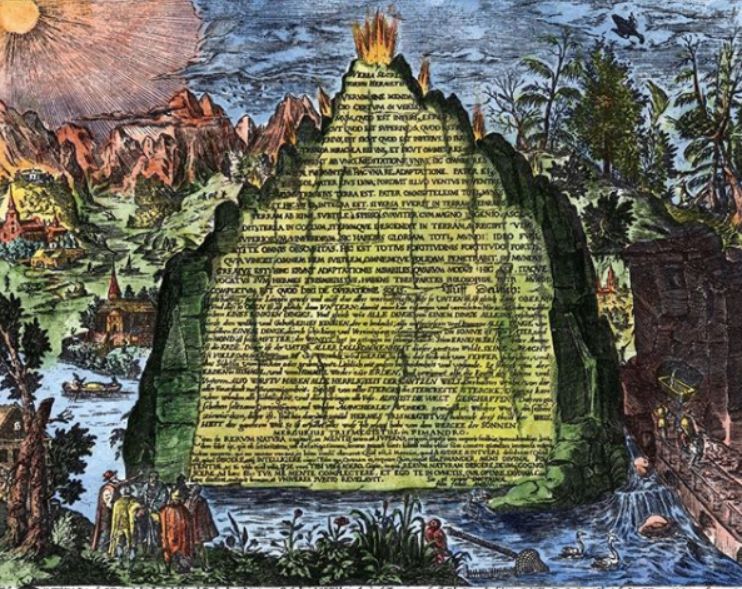

how people studied the natural world. Consider the hermetic and cabalistic

influences on John Dee (whereby the Rosicrucian Chymical Wedding featured a prominent image of Dee’s

Hieroglyphic Monad), Paracelsus’s quest for

nature’s hidden secrets, or Isaac Newton’s

alchemical experiments. At the same time, the mechanical systems of

Gassendi and Descartes, which were dependent on the unseen motion of invisible

pieces of matter, presented people in the seventeenth century with occult or

hidden explanations for natural phenomena that functioned much like earlier

systems that had depended on invisible sympathies or magical forces.

Most Europeans

believed that the natural world represented an important means of understanding

God as Creator; some even referred to the physical universe as the Book of

Nature, a metaphorical text that contained crucial knowledge about the divine.

Before the eighteenth century, most people would have found it unthinkable to

separate God Some of these traditions, like hermeticism, were first encountered

by Renaissance scholars trying to recover traces of the “golden age” of ancient

Greece and Rome. Others, like the Judaic tradition of the Kabbalah, had already

existed in Europe for hundreds of years but received closer attention from

Christian writers and philosophers in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries as

they searched for new and more powerful ways of

understanding their universe. This means that “scientific” inquiry often

had religious implications.

Physicians and other

medical practitioners commonly resorted to astrology in order to diagnose and

treat their patients, and the fundamental idea of magic, the belief that the

world contains hidden forces and powers that can be harnessed to accomplish specific

tasks, was seen as a powerful tool in the arsenal of some medical

practitioners. One such practitioner was the infamous medical reformer

Paracelsus born Theophrastus von Hohenheim (1493–1541) who, in the

early decades of the sixteenth century, combined a respect for nature’s secrets with a deep reverence

for God in his efforts to create an entirely new way of healing.

And while it seems

clear that attitudes toward magic did change in the seventeenth century and

that, for much of the eighteenth century, we find numerous people claiming that

a belief in magic was irrational, superstitious, and ignorant, there is evidence

that magical beliefs were not swept aside by scientific rigor and a commitment

to rationality, as the disenchantment theory would suggest.

The Enlightenment was

not a blank slate on which Europeans sketched a new world. It was more like a

piece of old parchment imperfectly scraped clean, still bearing traces of past

ideas around which modernity took shape.

The alleged secrets of the universe

To understand the

above we best go back around 1460, when the philosopher Marsilio Ficino

(1433–99) received a message from his patron, Cosimo de’ Medici (1389–1464),

the most powerful man in the Italian city-state of Florence. Up to this point,

Ficino had been hard at work translating the works of the ancient philosopher

Plato (c. 424–c. 348 BCE) from their original Greek into Latin, but his patron

had other ideas. He wanted Ficino to begin translating a different Greek

manuscript, one that Cosimo had only recently acquired. Obligingly, Ficino set

Plato aside and turned his attention to this new work. He soon realized that he

had stumbled across something very important.

The works that Ficino

translated became known as the Corpus Hermeticum, and

they contained the recorded wisdom of a mysterious figure known as Hermes

Trismegistus or Hermes “the Thrice-Powerful,” a contemporary of Moses and a

sage of unparalleled learning who had lived thousands of years earlier in

ancient Egypt. His writings promised to reveal the secrets of the universe to

those willing to learn, and this soon included Ficino, who became a passionate

advocate for the ideas of Hermes and was. instrumental in disseminating

them throughout Renaissance society. Ficino, along with many others, believed

that the Hermetic writings contained traces of ancient, uncorrupted wisdom that

might restore human understanding to the heights achieved by those, long ago, who

had known God and His creation in ways since lost to modern people.

The tradition

disseminated by Ficino is known as hermeticism, and it incorporated both

philosophical lessons on the nature of the divine as well as hands-on

instructions for magical work. Both hermeticism and the other tradition we

explore in this chapter, cabalism, are examples of learned magic – that is,

magic studied and practiced by the educated elite. This is very different from

the magic worked by healers, midwives, and others in small communities and

rural areas across Europe, practices usually labeled by historians as “folk

magic.” Learned magic had its roots in the distant past, and those who embraced

it did so with the hope that they would uncover secrets and mysteries that

would transform European society forever. This idea was so powerful and compelling

that it fundamentally altered intellectual life in Europe and continues to inspire people today.

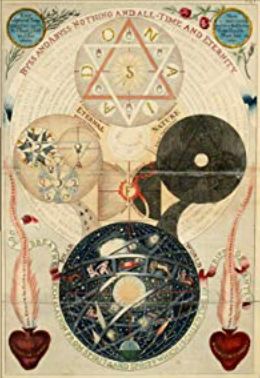

This also concerned

the Rosicrucian manifestos (referred to widely by among others popular

philosopher/occultists like Rudolf Steiner founder

of today's Waldorf schools) presented the recovery of ancient esoteric

wisdom as the key to humanity’s spiritual “reformation,” and together they

demonstrate how traditions such as hermeticism and cabalism evolved during the

sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, long after Ficino’s original translation

of the Corpus Hermeticum. There is little evidence

that the Rosicrucians

actually existed, however; their manifestos may have been part of a grand hoax,

or perhaps the idealistic imaginings of a single person. Even if this shadowy

society did not exist, however, the philosophy laid out in the Chymical Wedding and other works described a quest for

esoteric and occult knowledge inspired directly by the hermetic and cabalistic

traditions.

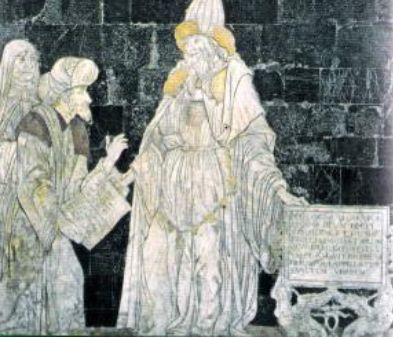

Hermes Trismegistus

as the founder of “Natural Magic” depicted in a

floor mosaic in the Siena cathedral:

From a magical worldview to Science

The shift in how

early modern people conceptualized and used occult causes leads us to the work

of the historian John Henry, who in contrast to Keith Thomas

Religion and the Decline of Magic (1971) has suggested that, rather than

'disenchantment', we should understand the fate of magic as one of

fragmentation in which philosophers retained some elements of magic and

rejected others.1

Thus early modern

chemistry included a wide range of different practices and methodologies,

including chrysopoeia,

the pursuit of metallic transmutation. When Herman

Boerhaave (1668 –1738) called for a reformation of chemistry in 1718

he was concerned about the respectability of the discipline, which he saw as

endangered by the fraud and trickery of quack alchemists. He knew very well, however,

that chrysopoeia was only a small part of the larger

practice of chemistry, even in the heyday of alchemy in the sixteenth and

seventeenth centuries, and he also understood that the discipline of chemistry

had already integrated fundamental alchemical ideas and practices into its

foundations. The study and transformation of matter, which had been central to

alchemical work for hundreds of years, also

defined the discipline of chemistry as it emerged in the eighteenth century.

Boerhaave’s deliberate attempts to draw a line between

“respectable” chemical work and the fraudulent practices of

transmutational alchemists were therefore not a wholescale rejection of

alchemy. Instead, it was a careful repudiation of particular alchemical

practices. He, and others like him, tried to establish chemistry as a

respectable discipline of academic study by breaking it apart into pieces. They

separated and then pruned away its most troublesome elements, leaving behind a

set of theories and practices with a deep (but unspoken) debt to alchemy.

Magical beliefs and

occult systems were already part of the natural philosophies that proliferated

in the Enlightenment. And when the educated classes of the eighteenth century

for example adopted Newtonian science with enthusiasm, they were unaware or uncaring

that its foundations were rooted firmly in religious and alchemical

traditions.2

Whose Enlightenment?

Science, as we understand

the word now, is a modern invention. Its careful methodology, its well-defined

disciplines, its culture of white coats and laboratories full of sophisticated

technology go back perhaps 150 years; in fact, the word “scientist” was coined

only in the late

nineteenth century by William Whewell. Before that, investigators of

nature called themselves "natural philosophers".

It is challenging to

talk about the Enlightenment as if it was a singular phenomenon because it

looked very different in different places. Some of the most important

articulations of Enlightenment ideals originated in France, but other countries

experienced the Enlightenment in different ways. Whereas many French thinkers

attacked the dogmatic traditions of the Catholic Church and its influence on

French society, people living in the German states were generally more

interested in reforming the practice and structure of government, and some

historians remain uncertain whether the Enlightenment actually took hold in

Britain at all. There are enough common elements across different nations,

however, to suggest that we can identify some universal beliefs and ideals that

defined “the Enlightenment” for most people.

It is widely accepted

that this period in European history defined much of what we in the West now

understand as “modernity.” In other words, the Enlightenment effectively

created the idea of the modern West as most of us experience it today. For

example, the separation of church and state enshrined in most modern

democracies was articulated most forcefully by Enlightenment thinkers, along

with ideas about religious tolerance and the importance of individual liberty.

Most of these changes were rooted in conscious and deliberate reactions against

the status quo that had prevailed in Europe for centuries.

As we generally

understand it today, to be enlightened is to be modern and open-minded. This is

no accident; the individuals at the forefront of the Enlightenment modeled in

their own lives a progressive ideal that equated rationality and tolerance with

modernity. Of course, this ideal had limits. Notions of tolerance and liberty

generally were applied only to white men and existed in clear opposition to the

practice of slavery which still existed in some

European colonies during the eighteenth century. Similarly, the famous cry

of “Fraternity!” or brotherhood that defined the spirit of the French

Revolution at the end of the eighteenth century excluded women and the poor. If

the Enlightenment gave us modernity, it also left us with some of the most

enduring social problems of the modern era, including racism, sexism, and a

persistent lack of respect for the working classes.

Though many people

living in the Enlightenment applied its ideals imperfectly, however, those same

ideals still represent a profound change in how Europeans understood their own

society as well as the wider universe. This was in part a culmination of some

of the trends described in previous chapters: for example, the slow but steady

rejection of ancient authority and its replacement by innovative methods of

inquiry and experimentation. At the same time, the strong connections between

natural philosophy, religion, and magic that had persisted for hundreds of

years became deeply and irrevocably strained in the eighteenth century. Some of

the most outspoken Enlightenment thinkers dismissed both organized religion and

magical beliefs as ignorant superstition, even as they quietly integrated

elements of earlier magical philosophies and practices into the new and

powerful natural philosophy that came to dominate the eighteenth century.

The emphasis on

reason in the Enlightenment tended to privilege particular ways of thinking

about the world and, in turn, created new institutions and priorities for

European society. If someone wanted to argue that the application of reason was

crucial to the development of a new and enlightened nation-state, then public

education would need to change in order to cultivate a properly rational

mindset in that nation’s citizens. Disciplines that had already embraced the

exercise of reason, such as the physical and mathematical sciences, could now

act as important exemplars for other disciplines, meaning that educated people

began to emphasize quantitative methods and approaches in fields like biology,

chemistry, and anthropology. At the same time, anything that might endanger the

exercise of reason, particularly the irrational belief in religious dogma or

the divine basis for the monarchy, needed to be minimized or suppressed. To

varying degrees, all of these changes happened in different places during the

Enlightenment.

While

self-consciously removed obvious traces of religion and magic from the wider

study of nature, they denigrated ideas that they found objectionable or

incompatible with their “age of reason,” calling them ignorant or

superstitious. Nevertheless, the world inhabited by these enlightened thinkers

was as filled with enchantment as it had been for people living in the

fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. What people had once called “magic,” the

Enlightenment called “science.” The triumphal narrative of the Enlightenment,

written first by “the enlightened” themselves and then taken up by those who came after them, depicted a glorious new

world ruled by reason and liberty, free from the tyranny of ignorance,

superstition, and mindless tradition. This rhetoric, all but overflowing with a

shining kind of idealism, is compelling even now, it seems familiar to many of

us today, perhaps because we still find traces of these ideals in many of the

institutions of the modern West. Ultimately, though, the Enlightenment was more

complicated and contradictory than this narrative suggests. Its proponents and

supporters tried to make a new world, and in some ways, they succeeded. In

other ways, however, they did not. Not unlike the natural philosophers who

tried to overthrow Aristotle in the seventeenth century but whose worldviews

were shaped irrevocably by the very thing they wanted to dismantle, the great

thinkers and reformers of the Enlightenment never quite escaped the society

they wanted to transform. True liberty and freedom were still reserved for the

elite few, while the pursuit of “reason” justified ideas that were decidedly

irrational.

And whatever the

successes and failures of the great project that was the Enlightenment, it is

worth looking back over the preceding centuries to remind ourselves how

radically the world changed for European people. Whereby the influence of

classical antiquity was where the European gaze was fixed on the distant past,

by the middle of the eighteenth century, Europe was in the midst of another

cultural movement defined instead by a gaze directed to the horizon ahead.

Nevertheless, the ancient world has never lost its hold on the Western

imagination, at least not entirely. From the eighteenth century, there have

been periodic revivals of classical themes in architecture, art, philosophy,

and literature, and to this day millions of people admire pieces of classical

statuary in museums and galleries or visit sites like the Acropolis of Athens

and the Roman Colosseum.

Where the influence

of antiquity has waned is in our collective understanding of the natural world.

The preeminence of Aristotle, Ptolemy, and Galen lasted for almost 2,000 years,

there increasingly where individuals who sought to understand the cosmos in

ways that were different from the philosophies of antiquity. In histories of

the “Scientific Revolution,” men like Copernicus, Paracelsus, Descartes, and

Francis Bacon are hailed as reformers and innovators who carved modernity from

the solid, weighty philosophies of the past in the same way that the artist

Michelangelo (1475–1564) described freeing a sculpture hidden within a block of

marble with chisel and mallet. These attempts to abandon the teachings of the

ancients were often imperfect or limited, but taken together they represent a

crucial shift in the European mindset that paved the way for new ways of

studying and understanding the world.

An informed and educated citizenry

The Enlightenment

vision of an informed and educated citizenry drove a series of developments in

the eighteenth century that opened up the methods and discoveries of science to

larger and larger audiences. A member of the middle classes living in 1750 would

have been exposed to mainstream scientific ideas in a way that hardly existed a

century earlier. Information was now conveyed in the vernacular rather than in

Latin, and natural philosophers recognized an opportunity both to educate the

public and to secure sources of financial support and social prestige by

staging demonstrations and exhibitions open to everyone, including women and

children. More than at any previous point in European history, the average

person living in the eighteenth century had opportunities to see and understand

the new world described by mathematicians, taxonomists, and geologists.

Some classical

philosophies, like Aristotelianism, had virtually no room whatsoever for a

deity, while others, like Epicureanism, had as their goal the diminution or

rejection of divine causation in the universe. With the widespread acceptance

of Christianity in the early centuries of the Common Era, however, large

numbers of people started to consider the role of an omnipotent, omniscient God

in the natural world. Some ancient philosophies of nature, like that of Plato

and his Neoplatonist followers, lent themselves relatively easily to the

Christian conception of a singular and all-powerful deity, but European

philosophers and theologians in the Middle Ages struggled to reconcile the

teachings of pagans such as Aristotle with the foundations of Christian belief

and doctrine. The intellectual flourishing of the Renaissance, sparked by the

recovery of ideas and texts new to Western Europe, included a deep fascination

with the prisca sapientia,

the ancient wisdom of Creation. Philosophers as disparate as Marsilio Ficino,

John Dee, Francesco Patrizi, and Robert Fludd sought to bypass centuries of

degeneration and touch the mind of God by reading the Book of Nature in new and

powerful ways, guided by those with an older and more perfect understanding.

The chaos of the

Reformation and the splintering of Christendom made that task more difficult as

there was now widespread and acrimonious disagreement about the very nature of

faith. Thus, from the sixteenth century onward we see a shift in how people understood

the relationship between God and His creation. Philosophers and naturalists

remained as pious as before; consider Johannes Kepler “thinking God’s thoughts

after Him,” or Paracelsus wandering the world in search of the divine secrets

hidden in nature. Yet, the religious anxieties that led Dee to converse with

angels, that landed Galileo in front of the Inquisition, and that drove both

Descartes and Gassendi to demonstrate the presence of God in their mechanical

philosophies all suggest that the relationship between God and nature, once

assured, was now the subject of question and doubt. When Newton suggested that

comets were sent periodically by God to correct imbalances in the vast cosmic

machine, yet another attempt to demonstrate God’s presence, the German

mathematician Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716) accused Newton of making God seem

like an inferior mechanic forced to tinker with an imperfect universe. In

Leibniz’s outrage, we catch a glimpse of profound anxiety that existed around

the turn of the eighteenth century, one motivated by depictions of God as mere

caretaker, winding up the cosmic watch and then walking away.

Newton, however, was

committed absolutely to the idea that the Creator remained present in His

creation, proposing at one point that universal gravitation was the invisible

hand of God at work in the cosmos. There is a deep irony, then, in the fact

that many philosophers in the eighteenth century interpreted the Newtonian

universe as one ruled not by God, but by mathematics and reason. The rise of

deism and its distant, unknowable God went hand-in-hand with the proliferation

of Newtonian science, thanks in part to efforts by leading Enlightenment

thinkers like Voltaire and Diderot to separate organized religion from secular

institutions. In response, some theologians and philosophers proposed new

evidence for the presence of God. For example, the English clergyman William

Paley (1743–1805) published his Natural Theology: or, Evidence of the Existence

and Attributes of the Deity in 1802 and argued that the presence of design in

nature was clear evidence for the existence of God. Paley is known today for his

“watchmaker analogy,” which claims that the intricate complexity found in many

living things must be the result of deliberate design rather than chance or

accident, and which remains a central idea held by present-day proponents of

creationism and “intelligent design.”

For all of these

developments, however, the typical European person in the eighteenth century

had a religious outlook that was largely unchanged from that held by previous

generations. Most Christians went to church each week, followed the teachings

of the Bible, and shared an understanding of God that would not have been out

of place in the seventeenth century. Popular religious movements such as

Pietism or the revivalist fervor of the Great Awakenings were grassroots

affairs, inspired not by sophisticated theologies but by broad social trends

and attitudes. In some cases, however, changes to religious attitudes and

practices had their roots in the ideas of the educated elite, as in the

increasing emphasis on religious tolerance that was encouraged and mandated by

Enlightened monarchs and governments.

For most people,

then, the unseen hand of God remained present in the universe. They were

untroubled by the problem of occult or hidden causes that had preoccupied

generations of philosophers and theologians. Even in antiquity, Aristotle and

Plato had struggled to define not just the role of hidden causes in the

universe but also the question of how to study phenomena that could be known

only by their effects. The universe bequeathed to the eighteenth century by

Isaac Newton solved this problem not by banishing or revealing occult causes,

however; on the contrary, he made occult causation central to his philosophy.

When Leibniz criticized Newton’s explanation for universal gravitation as

lacking a clear description of its causes, the latter agreed that his work

described “general Laws of Nature” whose “Causes be not yet discovered.” In

fact, Newton seemed unconcerned that the causes for gravitation were hidden.

His natural philosophy described the effects of gravity on the matter, what he

called “manifest Qualities”, while conceding that “their Causes…are occult.”3

Thus, Newton resolved the problem of occult or hidden causes by suggesting that

it was not a problem at all. Someone could use Newtonian methods to measure and

understand gravity’s behavior without needing to know anything at all about

what caused it.

That Newton was able

to sideline or ignore the problem of occult causation owes a significant debt

to the mechanical philosophies that had appeared some decades earlier. The tiny

atoms of Gassendi or the invisible corpuscles of Descartes were no less occult

than the sympathies and correspondences of the hermeticists

or the hidden properties of the Aristotelians; none of these things were

visible to ordinary perception. Yet, there had been relatively little concern

from contemporaries that these mechanical causes for natural phenomena were

hidden from sight – even if Cartesian corpuscles remained invisible, someone

still could infer their motions and behaviors by reference to natural laws and

geometrical principles. The widespread acceptance of mechanical explanations

for natural phenomena meant that, by the latter decades of the seventeenth

century, mainstream philosophies of nature had already embraced occult causes.

It was hardly more problematic for Newton to describe the action of an

invisible force such as gravity on similarly invisible pieces of matter.

Thus, the Newtonian

universe was one in which occult causation was the rule and not the exception.2

By 1750, most of the European middle classes understood the universe to be a

vast expanse in which the Earth was merely one planet among many. What a difference

from the small contained cosmos known to the educated elite of the Middle Ages,

which ended just beyond Saturn’s orbit at the sphere of the fixed stars. In

such a realm, where humanity was both the literal and figurative center of

everything, the interconnectedness of the premodern world made a deep and

intuitive sense to many people. The relationship between microcosm and

macrocosm, the practice of sympathetic magic, the influence of the heavens on

human health, personalities, and events, all sprang from an understanding of

the universe in which everything had its proper and natural place within a

complex web of correspondences and associations. By and large, however,

Enlightenment philosophers rejected the mystical and spiritual elements of the

Renaissance worldview in which humanity, Nature, and God all existed as part of

an interconnected whole. What persisted into the eighteenth and nineteenth

centuries was a desire to understand humanity’s place in the wider universe.

Attempts by the French biologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829) to

understand all life in the context of evolutionary change, by Carl Linnaeus to

integrate humans into biological taxonomies, and by Georges Cuvier to reconcile

human history with geological and paleontological discoveries all suggest that

this theme of interconnectedness was transmuted rather than dismantled.

Humanity had been displaced from the center of the physical universe by the

ideas of Copernicus and Galileo, but metaphorically we humans remained the

polestar around which all of Nature revolved.

1.“The Fragmentation

of Renaissance Occultism and the Decline of Magic,” in History of Science 46

(2008): 1–48.

2. Sir David

Brewster, Memoirs of the Life, Writings and Discoveries of Sir Isaac Newton

(Edinburgh, 1855), vol. 2, pp. 374–5.

3. Isaac Newton, Opticks, Based on the Fourth Edition London, 1730 (New

York: Dover Publications, 1952), Book III, Part I, Query 31, p. 401.

For updates click homepage here