By Eric Vandenbroeck and

co-workers

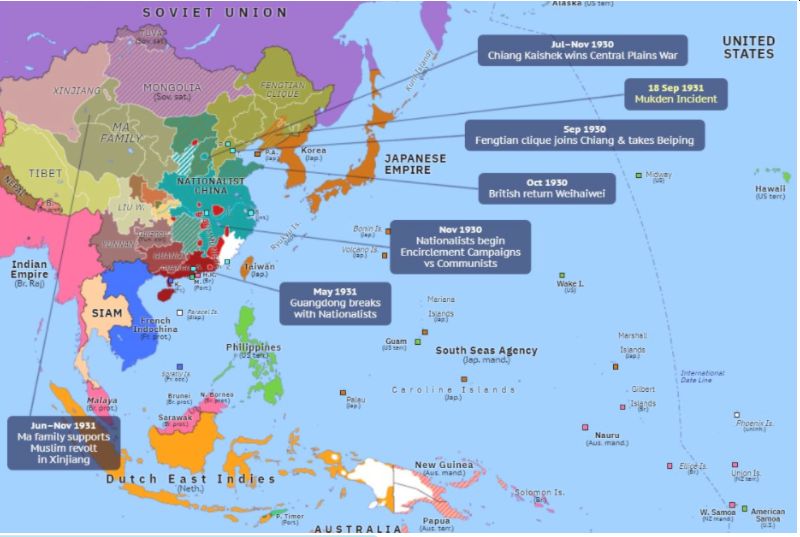

The geopolitical transformation of Asia

and the Pacific

Japan's leaders understood that war with the United States

was far from ideal. Still, it also ended another confusing stage of undeclared

war. The United States restricted Japanese access to critical industrial

resources, including oil, and supplied aid and finance to Japan's Chinese

enemy. The decision had much in common with Hitler's claim that the British

enemy could only be defeated by attacking a more prominent and potentially more

powerful opponent: fighting the United States (and the British Empire), it was

argued, would help somehow to resolve the conflict in China. In both cases, it

was evident that further warfare could not be conducted successfully without

access to additional material resources, whether in Ukraine or South East Asia.

After ten years of imperial expansion, Japan saw Eastern Asia in much the

United States viewed the Western Hemisphere – like its natural area of

domination that other powers ought to respect. Japanese leaders found it hard

to understand why the current situation should not be accepted as an

accomplished fact, and negotiations with the United States had begun from the

basis that Japan had a legitimate claim to be the leader of a new Asian order,

not from any sense that Japanese expansion was a violation of international

norms. In January 1941, Foreign Minister Matsuoka Yōsuke publicly rebuked the

United States for failing to make an effort to grasp the nature of Japan's role

in Asia, which was to 'forestall the destruction of civilization' and establish

a just peace.1 American intransigence was interpreted as an international

conspiracy to stifle and extinguish Japan's national existence. Unsurprisingly,

there was almost no common ground between the two sides when the Japanese made

efforts in 1941 to find a modus vivendi with the United States that would allow

them to resolve the China war on their terms and, at the same time, gain secure

access to the strategic resources needed to sustain the empire.

Ironically enough, the concern of Roosevelt and his

military leaders was focused much more on the European conflict than on the

Pacific. In his speeches during 1941, the president referred to Hitler and

Germany 152 times. Still, to Japan only 5.2 It was assumed that Japan could be

deterred by evidence of American naval power (in May 1940, Roosevelt ordered

the Pacific Fleet to stay permanently at Pearl Harbor following ocean

maneuvers) and by economic pressure on a state heavily reliant on American supplies

of metals and oil. As early as 1938, Roosevelt had called for a moral embargo

of oil, steel, aircraft, and finance for Japan, while money was made available

for pre-emptive purchasing of materials needed by Japanese industry.3 In

January 1940, the 1911 Commercial Treaty with Japan was abrogated. Following

Japanese entry into French northern Indochina in summer 1940, the Export

Control Act introduced formal restrictions on a range of strategic materials

for Japan, including aviation fuel, scrap iron and steel, iron ore, copper, and

oil-refining equipment. A year later, after southern Indochina was occupied,

Japanese assets were frozen. On 1 August, Roosevelt ordered that Japan apply

for federal licenses for all oil products, although he did not want all applications

rejected in case that pushed Japan too far. Japan was expected to be cowed by

the pending economic crisis provoked by American firmness. However, the

American ambassador to Japan, Joseph Grew, warned Washington that '-a threat

the Japanese are mere to increase their determination.'4 The complete

dislocation of Japan's economic situation indeed accelerated the shift to more

radical solutions.

During 1941 the Japanese political and military

leaders argued out the merits of trying to solve the China crisis by diplomacy

or by further warfare against Britain and the United States, a situation that

they had hoped to avoid. Like Hitler's decision to attack the Soviet Union,

Japanese leaders arrived incrementally when war seemed necessary and

unavoidable. American politicians failed to understand the impact the four

years of the China war had had on Japan. Japanese society was now geared for

total war, with shrinking supplies of goods and food for the civilian

population, heavy financial obligations, and popular culture of sacrifice and

austerity.5 For the United States, there was no sense of desperation in the

face of impending disaster. Still, for Japanese leaders, the failure in China

and the strangling effects of the embargo forced them to embrace solutions that

they would rationally have avoided. The uncertain nature of the Japanese

response to the crisis was personified in the summer and autumn of 1941 by

Matsuoka's ejection from the Foreign Ministry and the collapse of Prince

Konoe's government. The two principal architects of Japan's New Order were

superseded by General Tōjō Hideki, a military bureaucrat who personified the

ambivalence among Japan's elite over the country's options. As minister of war

in July 1941, Tōjō hosted the first meeting. It was agreed that the southward

advance to eliminate aid for Chiang Kai-shek and seize South East Asia's oil

and raw materials would now have priority. The army and navy, hitherto divided

over future strategy, temporarily pooled their planning. The German-Soviet war

removed the Soviet threat to Manchuria. Although the army doubled the size of

the Manchurian Kwantung garrison during the summer, if the opportunity arose to

profit quickly from imminent Soviet defeat, the southern advance to isolate

China made more immediate strategic sense.6 In late July, the army occupied

southern Indochina to cut off the principal supply route of aid to Chiang

(estimated at 70 percent of all supplies in 1940). The result accelerated the

drift to war. On 9 August, following the American oil restrictions, which

threatened to cut three-quarters of Japan's oil imports, army plans were

approved for war, starting in November. Navy preferences pushed the deadline

forward to October. The campaign was backed at an imperial conference on 6

September and justified in Konoe's words as a war of 'self-defence’.7

However, on 16 October, Tōjō succeeded Konoe as prime

minister and immediately promised that renewed efforts would be made to reach a

diplomatic solution that would pave the way for Asian peace under Japanese

guardianship, but not, as Konoe put it, 'plunge us immediately into war.' The

deadline for deciding on war or peace was shifted to late November. After days

of Cabinet discussion, during which the prospects for both options were

exhaustively examined, one more diplomatic effort was approved. At an imperial

conference on 5 November, the emperor was informed in the passive voice that

war could not be avoided if the final gambit failed. The Cabinet and military

staff saw war as something forced on them, not something they had chosen. Tōjō

authorized two plans to be presented to Washington: Plan A promised immediate

withdrawal from Indochina and China (except Hainan, the northern territories,

and Manchukuo) within two years, but expected a range of concessions on

restoring trade, closing off aid to China, and American agreement not to

intervene in Japanese–Chinese relations; Plan B was a more modest proposal to

promise no further aggression if the United States pledged to end the trade

embargo and repudiate any role in China.8 Both plans were presented to Washington

by the ambassador, Nomura Kichisaburō, and a veteran

diplomat, Kurusu Saburo. The plans were little more than wishful thinking by

November 1941, but the Japanese took them seriously as a compromise offer. On

22 November, American radio interception of Japanese diplomatic traffic

(codenamed 'Magic') read the message sent to the Japanese negotiators insisting

that 29 November was the final deadline for a political agreement: 'This time

we mean it, that the deadline absolutely cannot be changed. After that, things

are automatically going to happen.'9The American military was on full alert

from late November throughout the Pacific region, but the Japanese strike

remained unclear.

Roosevelt was not opposed to some form of compromise

if it kept the peace in the Pacific and met American interests. Still, his

secretary of state, Cordell Hull, who conducted the negotiations with Japan,

was resolutely against any agreement that left any part of China in Japan's

hands. Against the advice of the military leadership and the president's

wishes, he delivered a note to the Japanese negotiators on 26 November, making

clear that the extended run agreement could only be based on a restoration of the

situation before the occupation of Manchuria. This demand was not remotely

negotiable for Japanese leaders.10 Regarding this as an ultimatum, the

government discussed their choices on the 29th. Tōjō concluded that 'there was

no hope for diplomatic dealings' and the war option prevailed. Few Japanese

leaders seem to have actively favored war with the United States and the

British Empire. The decision was taken with a fatalistic acceptance that

fighting was preferable to humiliation and dishonor. Tōjō had told the imperial

conference on 5 November that Japan would become a third-class nation if it

accepted America's terms: 'America may be enraged for a while, but later she

will come to understand.'11 Once Japan had seized control of the oil and

resources it needed, it was hoped that the shock to American opinion would open

the way to an agreement that met Japan's national objectives. There was still

the option, revived in November that Japan might broker a peace settlement

between Germany and the Soviet Union, leaving the United States isolated, but

neither belligerent was interested.12

The day the Hull Note was delivered to Ambassador

Nomura, the Japanese navy's Mobile Striking Force under Admiral Nagumo Ch ⁇ ichi was sailing from its base in the Kurile Islands to

attack the American Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor. On 2 December, he received

the coded message 'Climb Mount Niitaka 0812',

authorizing the attack. Troop convoys were also on the move south from China

and Indochina towards the Philippines and Malaya. The latter was reported in

Washington, assuming that Japanese forces aimed to occupy Malaya and the Dutch

East Indies. Still, Nagumo's fleet remained sealed in secrecy until the hour of

the attack.

The plan to launch a surprise raid on Pearl Harbor

went back to the end of 1940 when navy leaders began serious preparation for a

southward advance, but it had been a topic in Japanese naval circles since the

1920s.13 The details were worked out by Kuroshima Kameto, the eccentric staff

officer to the fleet commander, Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku, who would lock

himself naked in a darkened room for days to think out planning solutions.14 A

seaborne air attack on this scale was a novelty. One model was the British

attack at Taranto in November 1940; Japanese embassy officials turned up in

Taranto the day after the raid to observe at close quarters its effect. They

were also much influenced by the German success in Norway in using air power to

neutralize Britain's much more significant naval presence. In spring 1941,

Japan's aircraft carriers were put under a single fleet commander to maximize

their striking power. Japanese aerial torpedoes were modified to operate in the

relatively shallow water of the docks at Pearl Harbor without sinking into the

seabed, and naval pilots were trained rigorously in low altitude torpedo and

dive-bombing. Although Yamamoto was one among several senior Japanese officers

anxious to avoid a clash with America, he understood that the Pearl Harbor

attack was an essential first step to prevent the Pacific Fleet from posing any

threat to the operations in South East Asia and the seizure of oil and

resources, which was the priority in the southern advance. However, when the

plan was presented to the naval staff, it was turned down because it

concentrated too much of Japan's maritime strength away from the Asian campaign

and put the carrier force at risk. Only Yamamoto's threat to resign forced the

navy's hand, and on 20 October, the plan was reluctantly approved. Nagumo's

First Air Fleet was tasked to destroy at least four American battleships at

anchor, together with the port facilities and oil storage. The force consisted

of 6 aircraft carriers with 432 aircraft, two battleships, two cruisers, and

nine destroyers; the naval element was modest for such a risky operation, but

for years Japanese naval strategists had seen air power as the critical element

in maritime warfare.

A surprise was complete on 7 December, although Nagumo

had been instructed to attack even if his force was detected as it approached

Oahu. The American failures are by now well known: aircraft were packed

together on the ground because the local commander, Admiral Husband Kimmel, had

been warned of possible sabotage; the limited radar system was closed down at

seven o'clock in the morning (the one sighting that occurred was thought to be

B-17s on exercise) and the Aircraft Information Center (modeled on the RAF

system) was not yet operational; there were no anti-torpedo nets; a handful of

Japanese midget submarines detailed to penetrate the harbor defenses in the

early hours of the morning before the air attack were spotted and one

destroyed, but no general warning followed; above all, the American

intelligence available prompted alert notifications that Japan was about to

act, but all reason dictated that this would be in South East Asia.15 In truth,

Yamamoto ran his luck to an exceptional degree in an operation that he judged

had only a fifty-fifty chance of success.

In the early dawn, two waves of Mitsubishi' Zero'

fighters, B5B 'Kate' bombers, and D3 'Val' dive-bombers were flown off the

carriers, totaling 183 in the first wave, 167 in the second.16 Despite the

intensive training, the operation was fraught with difficulty. The most

successful phase was destroying almost all the American aircraft on Hawaii –

180 destroyed, 129 damaged. The attack on the American capital ships met less

success. Out of forty torpedo bombers, only thirteen hits were scored; the

dive-bombers found it hard to distinguish targets and failed to do more than

damage to two of the eight cruisers moored; the second wave found the targets

now obscured by smoke. Not only was the hit ratio poor, but many Japanese bombs

failed to explode. One lucky bomb that penetrated the forward magazine achieved

the spectacular explosion and sinking of the USS Arizona, an iconic image from

the battle. The airmen returned to report devastating damage, but, like the

British raid on Taranto, the result was less spectacular once the smoke had

cleared. The American carriers were all at sea during the attack. Four

battleships were sunk, one beached; minor damage was inflicted on three others;

two cruisers and three destroyers were seriously damaged, and two auxiliaries sunk.

The twenty-seven fleet submarines sent by the Japanese navy to intercept any

breakout and then blockade Hawaii managed to drop only one oiler and damage one

warship in two months.17 The attack achieved more than Yamamoto had hoped, but

with more experience and better tactics, the raid could have earned much

more.

The attack did kill or maim Americans: a total of

2,403 dead and 1,178 injured. Roosevelt was relieved of the problem of

persuading a divided American public to join the war. Only a few days before

Pearl Harbor, he told his confidant, Harry Hopkins, that he could not bring

himself to declare war: 'We are a democracy and a peaceful people. But we have

a good record.'18 The Japanese attack galvanized American opinion and ended the

years of debate between isolationists and interventionists. He was defeating Japan

at all costs, united Americans of every opinion. For the British Empire, also

now threatened by Japanese aggression, the American fury at Japan threatened to

undermine any chance of a commitment to join the war in Europe until German and

Italian action relieved Roosevelt once again of the prospect of convincing the

American public to fight the European Axis as well. To secure a common

strategy, Churchill led a delegation to Washington on 22 December. In three

weeks of discussions codenamed 'Arcadia,' the British delegates tried to secure

American commitment to their view of the war. A tentative agreement had already

been reached earlier in March 1941 in informal military staff talks that Europe

was their joint priority. In the first meeting between Churchill and Roosevelt

at Placentia Bay in Newfoundland in August 1941, the 'Atlantic Charter' was

drafted. The defeat of 'Nazi Germany' was defined as the key to new world

order.

At the December summit, Churchill secured an assurance

from Roosevelt, despite the strong reservations of the American navy, that

Europe remained the priority. The two sides also took the unusual, indeed

unique, step in the war of pooling their strategic discussions in a common

forum, the Combined Chiefs of Staff, together with combined boards for

shipping, munitions output, and intelligence.19 There nevertheless remained

significant divergences. Roosevelt and his military staff were not attracted to

the idea of simply following British plans for what the many Anglophobes around

the president viewed as an 'empire war.' The initial priority was to prevent a

Soviet defeat. 'Nothing could be worse than to have Russia collapse,' he told

his treasury secretary. 'I would rather lose New Zealand, Australia, anything

else than have Russia collapse,' a view that sat uneasily with Britain's empire

interests.20 Roosevelt and his army commander-in-chief, General George

Marshall, assumed that a frontal assault on Hitler's Europe would be necessary

for 1942 to help the Soviet war effort. Still, the British were firmly opposed

to the risk – an argument only resolved later in 1942 when the operation became

manifestly unfeasible. To show that Roosevelt thought in terms of American

global strategy, he used the 'Arcadia' conference to launch on 1 January 1942,

only three weeks after the Pearl Harbor attack, a declaration on behalf of what

he called the United Nations, composed of all those many states at war with the

Axis. Like the Atlantic Charter, the statement of fundamental principles of

self-determination and economic freedom marked the point at which the values of

American internationalism superseded the importance of the older imperial

order. This shift became explicit as the war continued.

There was a curious sense of unreality in the weeks of

Anglo-American discussions. Across South East Asia and the Western Pacific, the

Japanese army and navy moved rapidly and decisively to achieve the southward

advance. The scale was quite different from 'Barbarossa.' Given commitments in

China and the operation against Pearl Harbor, the Japanese military could only

muster limited forces: 11 army divisions out of 51 available and 700 aircraft;

the navy could supply around half of its 1,000 aircraft, and had two carriers,

ten battleships, and 18 heavy cruisers to support the army's amphibious

operations.21 It was a campaign even riskier than Pearl Harbor because it

involved spreading forces very thinly between four primary operations:

The capture of the Philippines

The occupation of Thailand

The capture of Malaya and the Singapore naval base

Test of the Dutch East Indies

It was

Nevertheless, an exceptional moment of triumph in the

long war that Japan had waged since 1937. Western defenses were weak because

the British could spare little from the war in Europe and the Middle East, and

American reinforcement had only just begun. Dutch forces consisted of local

colonial troops after the German conquest of the Netherlands. Most British

Empire forces in the region were inexperienced Indian divisions. Daily digests

of the disaster arrived in London and Washington, starting with the sinking of

two British capital ships, sent originally at Churchill's insistence to deter

the Japanese. The battleship Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser Repulse,

confident as they sailed into the South China Sea that they were beyond the

range of any known Japanese aircraft and poorly informed about Japanese

capability, were sunk on 10 December torpedo bombers sent from bases in

Indochina. In a matter of a few hours, British naval power in the East was

extinguished. Only the Japanese gave the contest a name, the 'Battle of the

Malay Coast’.22

The two major campaigns against British Malaya and the

American Philippines protectorate began on 8 December. Pilots with specialized

training for extended overseas flights attacked the Philippines, flying from

Japanese Empire bases on Taiwan; as in Oahu, they found American aircraft lined

up on the tarmac at Clark Field and destroyed half the B-17s and one-third of

the fighters. Amphibious landings began on the 10th on the main island of Luzon

and made rapid progress towards the capital, Manila, which surrendered on 3

January. The United States commander, General Douglas MacArthur, appointed

earlier in the year, withdrew his mixed American–Filipino force south to the

Bataan peninsula. The force was doomed with no air cover and only 1,000 tons of

supplies shipped by an American submarine. MacArthur was evacuated to Australia

on 12 March to fight another day. Bataan was surrendered on 9 April. On 6 May,

after a grueling and tenacious defense of the island fortress of Corregidor,

the surviving American commander, General Jonathan Wainwright, gave up the

fight. The Japanese Fourteenth Army captured almost 70,000 soldiers, 10,000 of

them American. They were marched along the Bataan Peninsula to an improvised

camp; ill, exhausted, and hungry, they suffered beatings, killings, and

humiliation from Japanese Empire forces who suffered themselves from the

poverty of medical supplies and food and who had been taught to despise

surrender.23

In northern Malaya, General Yamashita Tomoyuki's

Twenty-Fifth Army began an amphibious assault on 8 December, fielding only a

few thousand men because of difficulty finding sufficient shipping. His army

was met by a poorly organized defense which crumbled in days, withdrawing in

confusion step by step down the peninsula, until Johore in the south was

abandoned on 28 January on the orders of the British commander-in-chief in

Malaya, Lieutenant General Arthur Percival, and the enormous empire force

evacuated to Singapore Island. Yamashita eventually commanded around 30,000 men

for the assault on the island, which was regarded by Japanese imperial

headquarters as a critical objective for any further advance into the Dutch

East Indies. Yamashita fielded far fewer than the estimated 85,000 British,

Indian, and Australian troops (as reinforcements arrived, the total reached

around 120,000) now crammed into an island base that had not been prepared for

defense against a landward invasion.24 On 8 February, Yamashita ordered two

divisions and the Imperial Guards to begin a night-time assault. Churchill

cabled that the defenders should fight and die to the last man, but this was

the stuff of empire adventure stories. After weeks of demoralizing retreats

against an enemy often invisible and brutal, the defending forces panicked. As

they fought to board the few remaining ships in Singapore Harbour,

Percival agreed with Yamashita to surrender. The capture of 120,000 men was the

most significant and most humiliating defeat in British imperial history.25

Other British outposts collapsed rapidly. On 25 December, Hong Kong surrendered

to the Sixteenth Japanese Army after holding out for eighteen days against

inevitable occupation; British Borneo, sabotaged by the retreating forces,

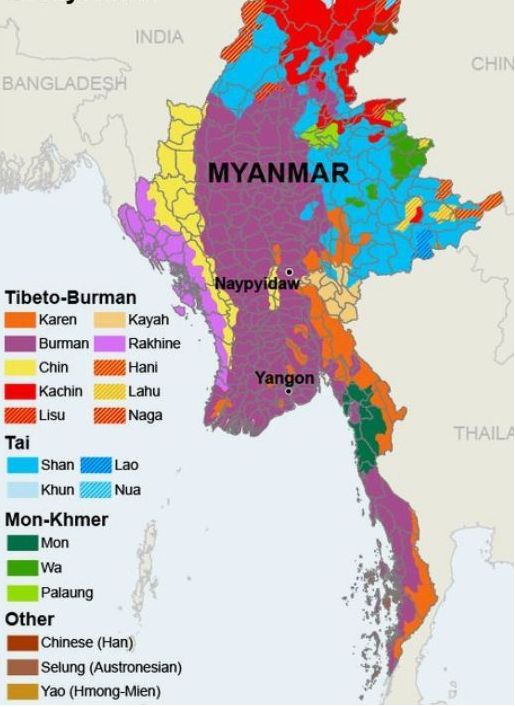

submitted on 19 January with its oilfield. Very soon, British Burma too came

under threat.

The campaign to capture Burma had not been the

Japanese military's initial intention. The original invasion force was designed

to eliminate the nearby British airfields that might have threatened the

security of the Malayan campaign. But Japanese commanders were tempted by the

evidence of just how weak British Empire forces proved to be to move further

and occupy Burma and threaten India as well. The Japanese army hoped that

further expansion might even force Britain to submit and the United States to lose

its will to fight.26 More prosaically, conquest would cut the supply lines from

India to Chiang's armies in southwest China and allow the Japanese to occupy

the rich rice-producing regions and the oilfield of Yenangyaung,

which produced 4 million barrels a year. The British had a poorly armed, mixed

force of around 10,000 British, Indian and Burmese troops and 16 obsolete

Brewster Buffalo fighter aircraft.27 They retreated in disorder to Rangoon as

the Fifteenth Japanese Army, under General Shōjirō

Iida, inaugurated the main Burma operation on 22 January with four divisions of

35,000 men. Because the Burma supply route was essential for China, Chiang had

offered the British the chance to deploy Chinese troops against a possible

Japanese assault in December. Still, General Wavell, now commander-in-chief in

India, not only brusquely refused the offer but also sabotaged Chiang's effort

to establish a Joint Military Council in Chongqing to oversee grand strategy

for the war in Asia.28 British unilateral seizure of supplies of Lend-Lease aid

for China, stored in Rangoon, exacerbated the tension between the two allies,

not least since the supplies made little difference. British Empire forces

abandoned Rangoon on 7 March and retreated hastily northwards. Chiang deeply

resented the patronizing attitude of the British, the 'superior race complex'

as one American eyewitness described it.29 'You and your people have no idea

how to fight the Japanese,' Chiang told Wavell in December, even before the

fact was evident. 'Resisting the Japanese is … not like colonial wars … For

this kind of job, you British are incompetent.'30

Chiang did not expect much more from the United

States, a wartime ally, but he wanted American assistance. Roosevelt agreed to

send a chief-of-staff to Chiang. The choice fell on the former military attaché

to China General Joseph' Vinegar Joe' Stilwell, famous for his sour view of

almost everyone except himself. Stilwell privately considered Chiang a

'stubborn, ignorant, prejudiced and conceited despot,' but he arrived at

Chongqing in early March 1942 to take up a post he accepted with reluctance.31

His first initiative was to persuade Chiang to let him take command of two of

the best remaining Chinese armies, the Fifth and Sixth, and use them to retake

Rangoon and keep the Lend-Lease supply route open. Chiang warned him that most

Chinese divisions were composed of little more than 3,000 riflemen with a few

machine guns, a handful of trucks, and no artillery.32 Undeterred, with no

combat experience and little or no intelligence on the enemy, Stilwell moved to

obstruct the Japanese in central Burma. The result was a predictable disaster.

With almost no air cover and scant regard for the Chinese officers, he was

supposed to command, Stilwell was forced to retreat in the face of a competent

Japanese campaign. Lashio in northern Burma was seized on 29 April, and by May,

the Japanese army controlled almost all of Burma. On 5 May, Stilwell fled

westward with a small party, leaving thousands of Chinese soldiers to their

fate. The Sixth Army was all but annihilated. Remnants of the Fifth struggled

in appalling conditions to reach the Indian frontier town of Imphal later in

the year, where Stilwell had already arrived on 20 May, blaming Chiang, the

Chinese generals, and the British for what went wrong.

A massive exodus of refugees hampered the long British

retreat to India, eventually estimated at around 600,000, most of the Indians

and Anglo-Burmans. It was challenging to keep the scattered forces of Major

General William Slim supplied or reinforced, and the ragged, exhausted remnant

that arrived in India had lost almost all military equipment. 'They DO NOT know

their job,' complained the overall British commander, General Harold Alexander,

'as well as the Jap, and there's an end of it.'33 British Empire casualties

numbered 10,036 out of the 25,000 who eventually fought in Burma, but at least

25,000 Chinese soldiers were lost, while Japanese losses amounted to only 4,500

for the whole campaign.34 An unknown number of refugees died in appalling

conditions as they struggled to cross the only two available passes into Indian

Assam.

Perhaps as many as 90,000 died of starvation, disease,

and the almost unpassable monsoon mud that, ironically, saved India from

Japanese invasion.35 Stilwell returned to Chongqing as overall commander of

American military personnel in China, which were few. Still, Burma and the

vital road to supply the Chinese was lost, along with any confidence Chiang

might have had that China would be taken seriously as an allied power. Chiang

accepted Stilwell back due to his continued desire to win American support, though

he now regarded the alliance as empty words.36 Further south, the conquest of

the Dutch East Indies was a foregone conclusion following the loss of

Singapore. By 18 March, the Allies surrendered the archipelago, leaving the

region's rich resources in Japanese hands. A string of Pacific islands was

captured to complete the whole campaign, from the American-held Wake and Guam

in the north to the British Gilbert and Ellice Islands in the far south. In

just four months, Japanese forces conquered almost the entire empire area of

South East Asia and the Pacific.

The army captured 250,000 prisoners, sank or damaged

196 ships, destroyed almost every Allied aircraft in the region, and cost 7,000

dead, 14,000 wounded, 562 aircraft, and 27 small vessels.37 This was a

lightning war (dengekisen) of the kind Japanese

military leaders had admired in the German campaigns of 1940 and hoped they

might achieve against the Anglo-Saxon powers.38 Japan's Blitzkrieg was easily

won, but at just the point that the German version had failed. The reasons for

Japanese success are not hard to find. Unlike the logistical problems that

plagued the German campaign, Japan's dominant navy and large merchant marine

were equal to the task of supplying men and equipment. The doctrine and

practice of amphibious warfare had been worked on for years with apparent

success.

On the other hand, the Western states had woeful

intelligence on the state of the Japanese armed forces, resulting in little

effort to gather up-to-date information and a product of complacent racism that

dismissed Japanese military capability. The governor of Malaya memorably told

Percival, ' Well, I suppose you'll see the little men off!'39 Japanese

intelligence, on the other hand, was thorough, gleaned by agents who mingled

with the large pool of Japanese living or working in South East Asia and drew

on Asian hostility to colonial rule. Japanese forces were well aware of just

how feeble the defense of the empire was likely to be; the army could field

thoroughly trained troops and pilots, many of whom had seen prolonged combat in

the harsh conditions in China.40 The troops available throughout South East

Asia to repel the Japanese invasion had few if any, among them who had seen

action. Poorly armed, with often limited training, increasingly prey to the

demoralizing fear that Japanese soldiers were unstoppable, they were generally

little match for the enemy. The conquest of Hong Kong exemplified the problem.

The financial and trading center for the British Empire in China, the colony,

was defended by two old destroyers, a few torpedo boats, five obsolete aircraft,

and army units riddled with venereal and other diseases. A Volunteer Defence Unit of local expatriates was formed with men from

fifty-five to seventy years of age. The Canadian brigades shipped in just

before Hong Kong fell had had almost no battle training.41 For years, European

imperial forces had been used to easy domination. Now they faced a rival empire

keen to sweep away white rule and equipped for the moment to do so.

The collapse of the British Empire in Asia and the

Pacific

The collapse of the British Empire in Asia and the

Pacific was complete. Conquest stretched from the frontier of northeast India

to the distant Gilbert and Ellice Islands in the South Pacific. The Japanese

high command had no plan to invade India and shelved the navy's proposal to

invade Australia's north and east coast because the army could not spare

further workforce.42 Nevertheless, on 19 February, the Australian port of

Darwin was bombed, while an effort to occupy Port Moresby in New Guinea, close to

Australian targets, was only turned back when a Japanese carrier was sunk and

another damaged by two American carriers in the Battle of the Coral Sea on 7–8

May. To rub salt in British wounds, Nagumo took his carrier force into the

Indian Ocean in April to bombard the British naval bases at Colombo and

Trincomalee in Ceylon (Sri Lanka), sinking three British warships and forcing

what was left of the Royal Navy's Eastern Fleet to retreat to Bombay (Mumbai)

to avoid further damage.43 So anxious were the British Chiefs of Staff at

Japanese threats to the Indian Ocean that they organized an invasion of the

French colony of Madagascar on 5 May (Operation 'Ironclad') to pre-empt any

Japanese landing, but it took six months of combat to force the surrender of

the Vichy garrison.44

The geopolitical transformation of the region in only

a matter of weeks produced a fundamental shift in the relationship between the

United States and its imperial ally. The surrender of Singapore with a few

days' fighting was contrasted unflatteringly with the courageous defense of the

Bataan Peninsula. The rapid collapse of British Empire defense in Asia was

added to the many failures of Britain's war effort and confirmed the American

military, and much of the American public, in their desire not to be drawn into

a strategy of rescuing an empire that had spent two years failing to save

itself.45 Roosevelt and his advisers moved swiftly to articulate a global

approach to compensate for Britain's debilitated world role, along lines

already widely discussed in Washington. The Johns Hopkins geographer Isaiah

Bowman, a key influence on Roosevelt's negative attitude to empire, assumed

that the time had come when the United States had 'to make a sudden shift into

a new world order' after years of being. ' Tentative, timid, doubtful.' In May

1942, Norman Davis, chair of the United States Council on Foreign Relations,

concluded that 'The British Empire as it existed in the past will never

reappear,' and added, 'the United States may have to take its place.'46 The president's

Advisory Committee on Problems of Foreign Relations, appointed in 1939, had

already outlined a commitment to colonial self-determination, freedom of trade,

and equal access to raw materials as hallmarks of the new order.47

Nothing divided American and British opinion so much

as the growing political crisis in India. Roosevelt had raised the issue of

Indian independence at the 'Arcadia' conference, to which Churchill, in his own

words, responded 'so strongly and at such length' that Roosevelt preferred not

to raise it in future discussions face to face (advice that he passed on to

Stalin).48 The president nevertheless saw the Indian issue as important, with

Japan poised for a possible invasion. In April 1942, they sent a message to

Churchill encouraging him to grant Indian self-government in return for Indian

participation in the war. Harry Hopkins, who was present when the telegram

arrived, was subjected to a night-long tirade from Churchill about the

president's interference. A month earlier, Churchill had sent Stafford Cripps,

the former ambassador to Moscow, to offer the Indians a complex federal

constitution in which Britain would keep responsibility for Indian defense.

Still, the Congress Party rejected it as a half-measure, designed to

'Balkanize' India, and the Indian situation remained deadlocked.

Nevertheless, for most British leaders, the issue of

the future of the British Empire was a matter for Britain to decide, not the

United States.49 Following Cripps's failure, American opinion hardened during

1942 against British imperialism. Gandhi wrote to Roosevelt in July urging the

Allies to recognize that making the world 'safe for freedom' rang hollow in

India and the empire. The Indian nationalist movement wanted the Atlantic

Charter and the United Nations Declaration to fulfill the pledge that Woodrow

Wilson's Fourteen Points had failed to honor at the end of the First World War.

Roosevelt's representative in India, William Phillips, sent the president

regular reports of the apathy and hostility of much of the Indian population

('frustration, discouragement and helplessness').50

It was an American journalist who coined the term

'Quit India' in the summer of 1942. Still, the time was soon taken up by the

Congress Party when the leaders met in early August to frame a resolution

asking for an immediate declaration that India would become independent. As the

viceroy Lord Linlithgow described it, what followed was 'by far the most

serious rebellion since that of 1857'.51 On 9 August, all the Congress leaders

were arrested, including Gandhi, and incarcerated for the rest of the war; by the

end of 1942, there were 66,000 Indians held in detention; by the end of 1943,

almost 92,000, many in unsanitary and overcrowded prisons, shackled and

fettered. The early arrests provoked widespread rioting and violence across

central and northwest India. The authorities kept a scrupulous account of the

destruction or damage to 208 police stations, 332 railway stations, 749

government buildings, and 945 post offices. There were 664 bomb attacks by the

angry, and mainly young, protesters.52 The British, relying on Indian police

officers and army units, lifted all restrictions on the use of force with the

Armed Forces (Special Powers) Ordinance, allowing the police and army to use

guns as well as sticks, and eventually the use of mortars, gas and strafing attacks

by aircraft to disperse crowds. Police opened fire on at least 538 occasions,

killing, according to official statistics, 1,060 Indians, but almost certainly

the figure was higher. Permission was given for general flogging as a

deterrent. After ordering twenty-eight men to be flogged in public with a dog

whip, one district officer wrote: 'Illegal without a doubt. Cruel? Perhaps. But

there was no further trouble throughout the district.'53 The India Office in

London made great efforts to restrict news of flogging and police violence from

reaching a wider public, but in Britain and the United States, anti-imperialist

lobbies highlighted the information. At its most ruthless, Churchill endorsed

the deliberate exercise of imperial violence, who loathed Gandhi, and feared

that the crisis might undermine the Raj entirely. Order was restored, but the

resentments that fuelled the rebellion would

resurface after 1945, when the wartime emergency was over.

During the summer of 1942, Roosevelt developed his

ideas about the future of the colonial empires without risking consultation

with his British ally. In June, the Soviet foreign minister, Molotov, visited

Washington, and Roosevelt chose the moment to test Soviet attitudes to the idea

of trusteeship as the gateway to eventual independence. Molotov approved since

anti-colonialism was orthodox thinking in Moscow. Roosevelt concluded by

explaining his view that 'the white nations … could not hope to hold on to these

areas as colonies'. These sentiments marked a fundamental difference between

American and British approaches to the probable post-war order. In discussion

with one of Roosevelt's close advisers on trusteeship in the Caribbean later in

the year, Churchill explained that, as long as he was prime minister, Britain

would cling to its empire: 'We will not let the Hottentots by popular vote

throw the white people into the sea.'54 Through most of the year following the

southern Japanese advance, American strategic planning was soured by

differences of opinion with the British. In May 1942, Brigadier Vivian Dykes,

the British secretary to the Combined Chiefs, complained that the United States

was set to put Britain in a satellite to America's position.55 The tension was

persistent over distinct views about the future of the British Empire and the

post-war international order. Although this did not inhibit collaboration, the

United States now joined with the Soviet Union and China to eliminate

imperialism old and new.

The new Empires

The territorial empires created by the Axis states

were unusual in several respects. Unlike the older empires, which grew

haphazardly over many decades, they were made in less than ten years, in the

German case in just three years, but were swiftly and destroyed by failure in

war. Yet despite the commitment to waging war, which placed severe demands on

the imperial center, all three Axis states set about building the

institutional, political, and economic bases for the new empires even while the

fighting was going on. The delusion that the empires were now permanent

features, whatever the outcome of the wider conflict, now seems difficult to

explain, even more so once the Soviet Union and the United States became the

principal Allied belligerents. But since the Axis wars were about building

empires, their fragile and improvised character was deliberately ignored in

favor of fantasies of a long imperial future.

The operation of the new empire areas had features in

common. Leaders in all three shared a language of 'living space' and approved

harsh measures to defend it once conquered. The empires constituted a mix of

different administrative and political forms rather than a coherent whole and

lacked common control structures (like the older colonial empires). The final

political shape of the new empire areas was held in abeyance until the end of

hostilities. Still, in each case, the dominant imperial power was not to be

restrained by conventional notions of sovereignty and international law. While

the war continued, large parts of the conquered territories were run by

military government or administration; the material resources of the captured

regions were intended to serve military needs as a priority. Under both

military and civilian administration, collaborators were sought to assist in

running local services, and the police and militia forces needed to help the

army maintain local security. The Japanese inherited the existing colonial

system of governance left by the defeated empires; the Germans and Italians

inherited state structures that could be exploited where necessary, even in the

hated Soviet system, to ensure local stability. In none of the new empires were

local, national sentiments fostered if they threatened the unity of the new

order or undermined the interests of the occupier. Any acts deemed to be

hostile to those interests were effectively criminalized. To establish

authority, extreme levels of terror were introduced that mimicked other

colonial contexts. Still, they exceeded them in sheer scale and horror:

deportation, detention without trial, routine torture, the razing of villages,

mass executions, and, in the case of Europe's Jews, extermination. Between

them, the new empires cost the lives, both directly and indirectly, of more

than 35 million people. If a fundamental difference existed between the Asian

and European experience, it lay in the extent to which racial policy shaped the

structure of the empire. Although Japanese soldiers and officials certainly

regarded the Japanese race as superior and had a particular loathing for the

Chinese, the ideology of empire was aimed at the idea of Asian' brotherhood',

with Japan very much the older brother. In Europe, and Germany in particular,

the structure of the new order was racially biased, with 'Germans' or

'Italians' at the apex of a hierarchical empire that condemned millions of the

new subject peoples to displacement, starvation, and mass murder. Japan's new

territories of the 'Southern Region' (Nampō) were

seen initially as an area where the mistakes made in trying to subdue and

pacify a large part of China might be avoided. These were colonial areas where

it was possible to pose as liberators of Asia from the Western yoke. The empire

in China was imposed on a people who did not see the enemy as a liberator but

as an occupying power whose remit rested in the end on the willingness to use

the army and military police (Kempeitai) to enforce

compliance. The Chinese territories occupied in the 1930s were nominally ruled

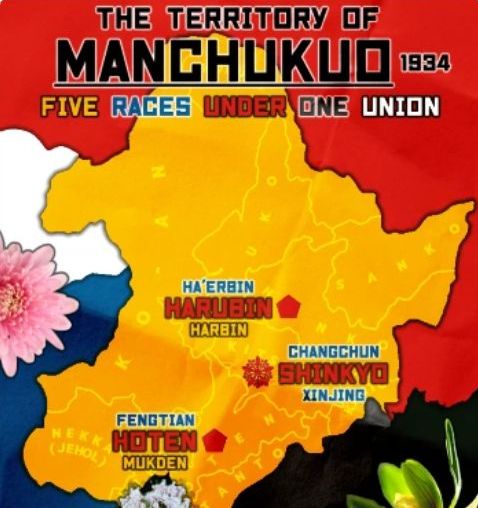

by Chinese puppet regimes, one based in Manchukuo, one in inner Mongolia, a 'Reformed Government' in

Beijing under Wang Kemin, the Shanghai Special Municipality in China's most

important city, and a Provisional Government in the Nationalist capital,

Nanjing, first under Liang Hongzhi, then from March 1940 under the former Chinese

Nationalist Wang Jingwei. In December 1939, Wang signed a formal agreement that

allowed Japan to station troops and embedded 'advisers' (whose advice was not

to be ignored) throughout the area of central and southern China occupied since

the start of the war in 1937.56 In none of these areas was Chinese sovereignty

a reality: North China was in effect run by the North China Political Affairs

Commission; Manchukuo was a colony in all but name; Wang's regime, while it

claimed to be the legitimate Nationalist government, was used instrumentally by

the Japanese supreme command to pressure Chiang Kai-shek into agreeing on a

feeling of peace and, when that failed, Wang was used to helping combat

Communist resistance through the Rural Pacification Movement, mobilizing the

limited military forces the Japanese allowed. Wang and his successor in 1944,

Chen Gongbo, were watched throughout by the Advisory

Group of Japan's China Expeditionary Force based in Nanjing.57

Throughout the area that became 'national' China under

Wang, the Japanese undertook widescale 'pacification' programs to create order at

a local level congenial to Japanese interests. Special Service agents,

civilians in distinctive white shirts emblazoned with the motto senbu-xuanfu ('announcing comfort'), were instructed in the

March 1938' Outline for Pacification Work' to 'get rid of the anti-Japanese

thinking … and to make [the Chinese] aware that they should rely on Japan'.

They were to be encouraged to observe 'the gracious benevolence of the Imperial

army' – a difficulty following the massacres in and around Nanjing a few months

before, and one of the many paradoxes confronted by the young idealists in the

Special Service as they tried to reconcile Japanese violence with the rhetoric

of peace and mutual co-operation they were told to broadcast.58 At the village

level, so-called 'peace maintenance committees' composed of local Chinese were

responsible for re-establishing order and educating the inhabitants into the

habit of bowing to any Japanese soldier they passed (or run the risk of random

violence). Following the mass 'Concordia League' pattern established in

Manchukuo to bind the population to loyalty to the emperor and his

representatives, Chinese neighborhood associations were used to express

pro-Japanese sentiment and to isolate those who refused to participate.

Individuals who obeyed were rewarded with a 'Loyal Subject Certificate.'59 For

ordinary Chinese, accommodation was the route to survival, dissent a sure path

to arrest, torture and death.

Many of the devices used to establish 'order' were

transferred to the Southern Region due to the immediate military occupation.

Planning for a possible southern advance had begun in 1940. In March 1941, the

Japanese army produced a document outlining 'Principles for the Administration

and Security of Occupied Southern Regions,' reaffirmed at the Imperial

Headquarters Liaison Conference in Tokyo in November, two weeks before Pearl

Harbor.60 There were three central policies, maintained in all the different areas

taken under occupation:

The establishment of peace and order

The acquisition of the resources needed by the

Japanese military and naval forces

Organizing as far as possible the self-sufficiency of

the occupied territories

Beyond that, the occupied area was divided up like

China into a patchwork of different dependent and satellite units, where no

decision was to be made about their eventual fate. The November meeting laid

down that 'premature encouragement of native independence movements shall be

avoided.' After the invasion, the captured areas were divided up for military

government (gunsei) between the army and navy

according to strategic priorities. The army administered Burma, Hong Kong, the

Philippines, Malaya, British North Borneo, Sumatra, and Java; the navy was

responsible for Dutch Borneo, the Celebes (Sulawesi), the Moluccas islands, New

Guinea, the Bismarck archipelago, and Guam. Malaya and Sumatra were united in a

single Special Defence Area as the core of the new

southern zone; Singapore, renamed Syanan-to ('Light

of the South'), was given a special status with its military administration,

and in April 1943 became the headquarters of the Southern Army when it moved

from the Indochinese capital of Saigon.61

The anomalies were Thailand and French Indochina, both

encroached on by the Japanese army, although not enemy states. The Thais were

induced to allow Japanese troops and aircraft access to the fronts in Malaya

and Burma, but the result was a form of occupation. The Thai government of

Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram

signed an alliance with Japan on 11 December 1941. On 25 January, following

bombing attacks by Allied aircraft, declared war on the Allies, assuming they

were joining the winning side. The Japanese promise that territory in Malaya,

regarded as part of historic Thailand, would be restored. On 18 October 1943,

the northern Malayan provinces of Perlis, Kedah, Kelantan, and Terengganu were

indeed transferred to Thai rule.62 French Indochina, under a Vichy colonial

regime, had been forced to accept Japanese troops in the north in summer 1940,

and a complete occupation in July 1941, when Saigon became the headquarters of

the Southern Army. On 9 December 1941, a Franco-Japanese Defence

Pact confirmed Japan's right to operate from French territory with French

assistance. Field Marshal Yoshizawa Kenkichi was appointed Ambassador

Plenipotentiary to oversee Japanese interests. The commander of the Southern

Army, Field Marshal Terauchi Hisaichi, treated

Indochina as if it were occupied territory.63

The acquisition of the Southern Region prompted the

establishment in Japan of a structure to oversee the new imperial project in

what was now called the Great East Asia War. In February 1942, a Council for

Construction of Greater East Asia was set up. On 1 November, a formal Ministry

for Greater East Asia was appointed. However, its remit did not extend to the

Malayan–Sumatran Special Defence Area, which,

together with the rest of the Dutch East Indies, was declared in May 1943 'to

belong to Japan for all eternity' as integral elements of the Japanese colonial

empire.64 The south also now joined the Great East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere,

an amorphous concept of Asian collaboration under the leadership of the

Japanese Imperial Way, first given the name by Matsuoka in a newspaper

interview on 1 August 1940. The sphere was supposed to bind together the

peoples of East Asia and the Pacific, once free from Western domination, so

that they could march forward together to a peaceful and prosperous future. It

quickly became the touchstone of planning in Tokyo for the occupied areas,

embedded in political and media discourse as a means to legitimize Japanese

occupation as something other than mere colonialism. The ideology of harmony

and unity generated for the more expansive empire was matched by a political

transformation in Japan itself, when in August 1940, the political parties

dissolved themselves and formed an Association for the Promotion of a New

Order, rejecting liberal parliamentarians in favor of a joint commitment under

the emperor to promote the Imperial Way in Japan and its territorial conquests.

The population was united in a single Imperial Way Assistance Association.

According to the then prime minister, Prince Konoe, political harmony in Japan

was the precondition for Japan to take the 'leading part in the establishment

of a new world order’.65 Nation and empire became culturally and politically

inseparable. The increasing militarization of Japanese politics prepared

the background conditions in which their ideas could be implemented. Their

ideas were articulated in the context of growing

hostility with the Western colonial powers over Asia and, eventually, the

Second World War that served as the appropriate context for the rise of

Japanese nationalism.

The ideological underpinning of the Japanese New Order

was essential to the self-understanding of the thousands of officials,

propagandists, and planners who radiated out from Japan to help run the new

territories. They were animated by an idealistic view of what Japan could now

achieve for the whole Asia-Pacific area. They were welcomed initially by that

fraction of the occupied population who hoped that the rhetoric of the

Co-Prosperity Sphere meant what it said. The problem for the Japanese intellectuals

and writers mobilized to promote the ideology was the tension between the claim

that Japan was ending European and American colonialism and the need to

position Japan clearly as the 'nucleus' or 'pivot' of the new order. In Java,

the propaganda team that accompanied the military administration developed the

idea that Japan was only regaining the central position that it had played

thousands of years before as the cultural leader of an area from the Middle

East to the American Pacific coast. 'In sum,' claimed the Japanese journal Unabara (Great Ocean), 'Japan is Asia's sun, its origin,

its ultimate power.' The occupiers promoted a 'Three-A Movement' to get

Indonesians to understand that their future lay with 'Asia's light, Japan;

Asia's mother, Japan; Asia's leader, Japan.'66 In the end, the new sphere was

designed to create a form of empire consistent with Japan's cultural heritage

and distinct from the West. According to the Total War Institute in a

publication in early 1942, all the peoples in the sphere would obtain their

'proper positions,' the inhabitants would all share a 'unity of people's minds,

but the sphere would have the empire of Japan at its center.67

Among those who were initially enthusiastic about the

idea of a different Asia, the reality of military government and Japanese

intervention soon created disillusionment. The Indonesian journalist H. B.

Jassin, writing in an arts magazine in April 1942, complained that the people

had 'absorbed everything Western and denigrated everything Eastern.' Still, by

contrast, he thought the 'Japanese are great because they could absorb the new

while retaining what was theirs.' But in his post-war memoirs, he recalled the

bitter irony of enthusiasm for the rhetoric of co-operation and harmony 'which

later turned out to be nothing more than beautiful balloons, each bigger and

more brilliantly colored than the last, but their contents only air.'68 Even

the head of the Japanese propaganda mission in Java, Machida Keiji, later

acknowledged how futile the ideological effort was, given the reality of

military rule and the hostility of much of the army leadership to ideas that

would excite Indonesian ambitions: 'The great banner of the "Greater East

Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere" in fact meant only a new Japanese colonial

exploitation, a sign advertising beef that is dog meat.'69 The military

occupiers were, in general, more pragmatic and more self-centered than the civilian

ideologues. The menace at the core of Japanese rule was made evident at once on

the arrival of Japanese forces. In the East Indies, the military administration

immediately banned Indonesian nationalist symbols, imposed censorship,

prohibited all meetings, outlawed the possession of firearms, and set a curfew.

Suspected looters were publicly beheaded or left bound hand and foot in the sun

to die. Javanese had to bow low to all Japanese soldiers and, if they failed,

would receive a slap across the head, or worse. So widespread was the local

Chinese's abuse called the early occupation 'the period of people struck by

moving hands.'70 In Malaya, a wave of executions and beatings followed victory,

aimed at any who were thought to be anti-Japanese or to retain pro-British

sentiments. According to the euphemistic language of the military

administration, the motive was 'to indicate the right way to eliminate their

possible mistakes.' Severed heads were left on poles in the street as a warning

to others.

In Singapore, the Kempeitai,

housed in the Young Men's Christian Association building, undertook

'purification by elimination' (sook ching), a term the German SS would have

understood. The main target was the Chito eliminate the Chinese) and included

teachers, lawyers, bureaucrats, and young Chinese men linked to political

forces in Nationalist China. Estimates of the number executed vary widely, from

5,000 to 10,000. Purification in mainland Malaya may have accounted for 20,000

more.71

In all the occupied areas, the three policies agreed

on in November 1941 were applied with mixed results. The pursuit of order

combined the threat or reality of draconian punishment with strategies for the

same pacification and self-government committees at the village level practiced

in China. In Malaya, Peace Committees were set up to restore order, using a

large number of the incumbent Malayan officials inherited from the British

colonial administration. Complaints or bad work were judged to be anti-Japanese

and risked severe punishment. In time, neighborhood associations were

introduced, like those in Japan and northern China, while local police and

volunteers were enlisted in the paramilitary militia and auxiliary police

forces. Eventually, local 'advisory councils' were inaugurated in most

territories, but they had no authority and allowed the Japanese officials and

military to gauge local opinion without conceding responsibility. Mass

movements of solidarity, now modeled on the Imperial Way Assistance Association

in Japan, were created to act as social discipline. In the Philippines,

political parties were dissolved, and a single 'Association for Service to the

New Philippines' was established, superseded in January 1944 by a 'People's

Loyalty Association.' Overseeing their conduct was the Kempeitai,

attached to each army unit.72 They dominated the policing of the territories,

but they could do so only by recruiting large numbers of agents and spies

willing to denounce their compatriots. The numbers of military police were

small, spread across a vast territory. In Malaya, at the peak of activity,

there were only 194 Kempeitai in service.73 Their

behavior was entirely arbitrary, and they could also discipline Japanese

forces, even senior officers, if they chose. Accounts show many cases where

completely groundless accusations were made: if the victims were fortunate,

they would survive hideous tortures until their innocence was demonstrated; if

not, they confessed to improbable crimes and were executed.

The colonial character of Japanese rule on the ground

indeed imposed a prudent accommodation on the occupied populations. Still, it

also provoked armed and unarmed resistance, which was treated with exceptional

severity. Opposition was made possible by the sheer geographical extent of the

Japanese-controlled territory, where thinly spread garrison and police forces

were confined to the towns and the rail lines that linked them. Mountain

terrain, forest, and jungle allowed guerrilla forces to operate hidden and

mobile campaigns. By the time the southern area was occupied, Japanese troops

had had much experience with resistance in Manchukuo and China, led primarily

by Chinese Communists. In Manchukuo, the Japanese army instituted a simple

system of rural resettlement into 'collective hamlets' to cut guerrillas off

the isolated villages and farms that helped supply them. By 1937 at least 5.5

million people had been displaced into some 10,000 hamlets. In 1939 and 1940,

following a program of roadbuilding to ease communications, a major operation

was launched to rid Manchukuo of all armed resistance. Some 6–7,000 Japanese

soldiers, 15–20,000 Manchurian auxiliaries, and 1,000 police combat units were

mobilized. Villages suspected of giving succor to the resistance were burnt

down, and their inhabitants, men, women, and children, massacred. The security

units adopted what the Japanese called the 'tick' strategy of sticking to an

identified guerrilla group and following it relentlessly until it was cornered

and destroyed. Thousands of guerrilla hideouts were discovered and eliminated,

and by March 1941, resistance had all but come to an end.74

Much of the resistance in the Southern Region was also

conducted by communists, who were regarded as a particular menace by the

Japanese authorities. Overseas Chinese played a significant part since they

were linked with the broader war in China. By 1941 there were 702 'Salvation

Movement' groups across South East Asia supplying aid and moral support to the

Chinese war effort, both nationalist and communist.75 In Malaya, communist

resistance began almost at once with the founding of the Malayan People's Anti-Japanese

Army, supported by a broader Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Union. By 1945, the

army was estimated to have between 6,500 and 10,000 fighters, organized in 8

provincial regiments, with assistance from perhaps as many as 100,000 organized

in the Union.76 By this stage, the resistance had the support of Allied

infiltrators organized through the British Special Operations Executive.

Between 1942 and the end of the war, the resistance had mixed fortunes.

Japanese counter-insurgency counted on the support of spies and agents,

including none other than the general secretary of the Malayan Communist Party,

Lai Tek, who in September 1942 betrayed a top-level guerrilla meeting in Batu

Caves Selangor, allowing the Japanese to ambush and kill prominent Communist

leaders. During 1943 major security operations devastated the guerrilla ranks,

and for much of the time, mere survival among the dense jungle and mountains

was the priority. The movement engaged in isolated acts of sabotage and

assassination of those who worked for the Japanese authorities, but regular

Japanese inducements to offer bribes or amnesty to the resisters depleted their

number. Those in the Union suffered more since they were not mobile like the

guerrillas. Some resettlement schemes were operated to prevent remote villages

from assisting the rebels, but on nothing like the scale in Manchukuo or the

later dislocation of millions during the British 1950s counter-insurgency.

Whether the Anti-Japanese Army claims that 5,500 Japanese forces and 2,500

'traitors' were killed matched reality or not, resistance remained a constant

irritant to the occupying power and a reminder that 'peace' and 'harmony' in

the new empire were merely relative.77

In the Philippines – outside Malaya, the only other

leading site of sustained resistance – the overseas Chinese, both communist and

nationalist, also played a part. In this case, the Chinese constituted only 1

percent of the Philippines population, where they amounted to more than a third

of the Malayan population. Since many were young male immigrants, they avoided

Japanese 'cleansing' operations by joining small Chinese left-wing resistance

movements set up in early 1942, the Philippine Chinese Anti-Japanese Guerrilla

Force, and the Philippine Chinese Anti-Japanese Volunteer Corps. In cities,

resistance was led by the Philippine Chinese Anti-Japanese and Anti-Puppet

League. Right-wing Chinese, linked to the mainland Nationalists, organized four

small groups, fragmenting even further the Chinese effort.78 The chief

communist resistance group was Filipino, the People's Anti-Japanese Army (Hukbalahap), formed under the leadership of Luis Taruc in

March 1942. The first battle they fought against 500 Japanese troops was

commanded by the redoubtable Felipa Culala (known as

Dayang-Dayang), one of many women who joined the armed resistance. By early

1943 there were an estimated 10,000 Huk fighters. Still, a force of 5,000

Japanese troops deployed in March that year on the main island of Luzon

inflicted a severe defeat, compelling the Huk to focus on survival and

recruitment, as in Malaya.79 By 1944, the Huk again numbered perhaps 12,000 men

and women. Still, they were now armed by the United States with weapons and an

effective radio network, which proved invaluable, particularly on the smaller

island of Mindanao.80 They eventually linked up with American-led guerrillas to

support the later United States invasion in autumn 1944.

The second strand of Japan's occupation policy, the

supply of resources for the occupiers and the Japanese war effort, proved more

complex than the planners could have envisaged. Directives in each of the

occupied territories made it clear that Japanese needs took priority. This

meant forcing the people's livelihood upon them, as in Indochina, which was

still under limited French rule.59 The primary rationale behind the southern

advance had been to take control over critical resources lacking elsewhere in the

Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, and that meant bauxite and iron ore

from Malaya principally, and oil and bauxite from the Dutch East Indies.

Although the Western Allies suffered from the collapse of rubber and tin

supplies from Malaya and Thailand, neither was necessary for Japan. The

collection of rice and other foodstuffs was needed for the local troops and the

Japanese home islands.

A wide range of other goods was requisitioned or

purchased for the occupier's use and could not be withheld. In August 1943, the

military administration in Malaya published an ordinance 'for the Control of

Important Things and Materials', giving the Japanese the right to commandeer

whatever was needed. To cope with the difficulty of organizing a decentralized

economy in Malaya, a Five-Year Production Plan was published in May 1943,

followed a month later by a Five-Year Industrial Plan. To ensure supplies, monopoly

associations were set up, together with central agencies for price control and

licensed trade. Still, declining means of transport and widespread corruption

made it difficult to turn plans into reality.81

Some cases, supply for the home island economy was

successfully sustained, but the overall results scarcely matched the optimistic

expectations of the supreme command. Bauxite exports from Malaya and the

Indonesian island of Bintan to feed the aluminum

industry reached 733,000 tons by 1943. Still, the output of Malayan manganese

ore, affected by British demolitions, sank from 90,780 tons in 1942 to just

10,450 tons in 1944. Iron-ore imports from the south reached 3.2 million tons in

1940 but fell to 271,000 tons in 1943 and 27,000 tons in 1945. Ironically, the

high-quality iron ore of Malaya had been developed by Japanese firms in the

1930s, supplying 1.9 million tons in 1939 for Japan's economy.

Supply was maintained only by expanding output in

occupied North China.82 The two primary export industries of South East Asia,

rubber and tin, were allowed to languish, creating widespread unemployment and

poverty among the Malay workforce. Japan needed only around 80,000 tons of

rubber a year (and seized stocks of 150,000 tons), so production fell to less

than a quarter of pre-war output by 1943; 10–12,000 tons of tin was all that

was needed, and as a result, output fell from 83,000 tons in 1940 to just 9,400

tons in 1944.83 The essential resource was oil, which had triggered the

decision to invade. The valuable oilfields of Borneo, Sumatra, Java, and Burma

produced annually more than enough oil to cover the needs of the Japanese armed

forces. The attempt by the British and Dutch to render the oil wells mainly

inoperable failed. The Japanese troops had expected it to take up to two years

to get the flow of oil back to the pre-war level. Still, some installations

were working again within days, most significantly the major field at Palembang

on Sumatra, which produced almost two-thirds of the region's oil. Some 70

percent of the oil industry personnel were sent from Japan to manage the

exploitation, leaving the home industry short of skilled men. By 1943, southern

oil was flowing at 136,000 barrels a day, but almost three-quarters of this

were consumed in the south of the war zone, leaving the home islands with

little bonanza.84 In 1944, Japan imported only one-seventh of the oil that had

been available before the American embargo, 4.9 million barrels instead of 37

million, a situation that had worsened with an American air and sea blockade

which Japanese military leaders had failed to anticipate.85 Oil had made the

war seem necessary, but war consumed the oil.

The final policy objective – to make the Southern

Region self-sufficient and reduce the need for trade or transfers from the

Japanese home islands – succeeded only at the cost of widespread impoverishment

and hunger for the indigenous populations. Self-sufficiency was challenging to

impose at short notice on areas that were primarily export-based colonies

serving the world market. Sales to the West had made it possible to import the

food and consumer goods needed for the home population. With the collapse of

multilateral trade, the occupied areas were forced to rely on what could be

produced locally or bartered. The south was not integrated within the yen

currency bloc operated in China, Manchukuo, and Japan. The financial system

broke down in most of the areas following the collapse of the colonial banks,

except in Indochina and Thailand; since there were no local bond markets, and

the failure of exports undermined taxation, the Japanese military

administrations simply printed money as military scrip and declared it to be

the legal tender.86 Financial self-sufficiency was enforced by harsh punishment

for anyone who refused to accept the crudely printed Japanese notes or retained

old money stocks. 'Tremble and obey this notice,' ran the posters put up in Malaya

to announce that only military scrip – nicknamed 'banana money' from the banana

tree illustrated on the notes – was valid currency. Violations were met with

torture and execution. Efforts to reduce the money supply to prevent

hyperinflation included large-scale lottery sales and taxes on cafés, amusement

parks, gambling, and prostitution (so-called 'taxi hostesses').87

Inflation was, nevertheless, unavoidable as a result

of competition for food and goods from the Japanese garrison forces, despite

efforts to impose coercive price controls. The difficulty of controlling the

economies of so large an area led to widespread corruption, hoarding, and

speculation, usually at the expense of the poorer urban population. Collapsing

transport networks made it difficult to move rice from surplus to deficit

areas, while damaged irrigation systems and the loss of draught animals to disease

and requisitioning led to falling yields.88 As Japanese demands rose, so the

living standards of the bulk of the population deteriorated. In Malaya,

unsuitable for large-scale rice production, the population consumed more root

vegetables and bananas, but these provided an average of only 520 calories a

day. Supplementing food by resort to the black market was unavailable for

ordinary workers. In Singapore, the cost-of-living index rocketed from an index

figure of 100 in December 1941 to 762 by December 1943 and 10,980 by May 1945.

A sarong in the Malayan state of Kedah had cost $1.80 in 1940, but $1,000 in

early 1945.89 Malayans were observed to work barefoot and almost naked, with

rags instead of clothes. In Java, rationing by 1944 only provided 100–250 grams

of rice a day, too little to sustain everyday life. Estimates suggest that 3

million Javanese died of starvation under the occupation, even in an island

initially self-sufficient in foodstuffs. Signs appeared in the streets of

Batavia, 'The Japanese must die, we are hungry!'90 In Indochina, the French

agreement in 1944 to allow the Japanese to extract higher levies from the rice

crop left the peasant farmers in Tonkin desperately short of food. Here, too,

an estimated 2.5–3 million died of starvation over the winter of 1944–5

In addition to the crisis in living standards,

occupied populations had to cope with growing demands from the occupiers for

compulsory labor service, which imposed a harsh regime on an already

debilitated workforce. The model had been worked out in Manchukuo, where the

Japanese authorities ordered that all men aged between sixteen and sixty had to

do four months of forced labor (rōmusha) for the

Japanese army every year; for families with three males or more, one was

obliged to undertake one year of labor service. An estimated 5 million Manchurians worked for the Japanese, aided by

2.3 million laborers deported from the North China area between 1942 and

1945.91 In the Southern Region, shortages of labor to construct roads,

railways, airbases, and fortifications led to the imposition of rōmusha labor battalions, most notoriously with the

construction of the Burma railway linking Bangkok to Rangoon, on which an

estimated 100,000 Malays, Indonesians, Tamil Indians, and Burmese died of