By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Italy’s Meloni and the False Promise of

Moderation

As a far-right tide sweeps

across the Atlantic, European liberal democrats are searching for a strategy.

Some believe they should erect stronger firewalls by refusing to join

coalitions that include the far right to prevent its leaders from gaining

political power. Others—for instance, Manfred Weber, the president of the

center-right European People’s Party in the European Parliament—have advocated

cooperating with certain far-right parties in the hope of cajoling specific

leaders away from extremes by offering them a seat at the table.

Other centrists still

assume that when right-wing populist provocateurs take office and face the real

messiness of governing, they will move toward the center. Those who cling to

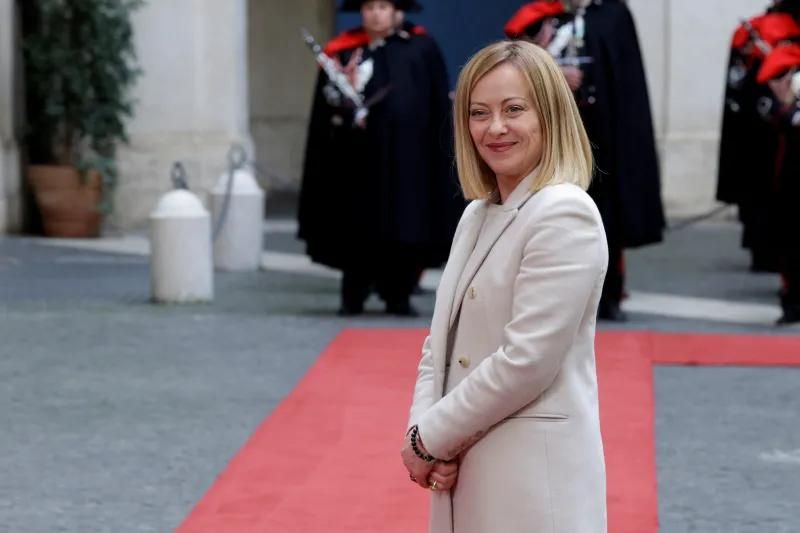

this prospect hold up Giorgia Meloni, Italy’s far-right, pro-American prime

minister, as an example. When Meloni rose to power in 2022, liberal democrats

were deeply concerned: a self-declared admirer of Benito Mussolini, she

presided over a party that prided itself on its fascist roots. But Meloni

quickly maneuvered to dispel those worries, extending her predecessor’s support

for a recently invaded Ukraine and affirming Italy’s staunch commitment to

NATO. Given U.S. President Donald Trump’s predatory approach to Europe, some

Europeans—particularly EU officials and Ukrainian leaders—imagined that figures

such as Meloni could serve as “Trump whisperers,” persuading the American

president to stick with European allies. Trump himself has often spoken warmly

of Meloni, suggesting in December that if they worked together, they could “straighten

out the world a little bit.”

But the hopes that

moderates have harbored about Meloni are misplaced. As the transatlantic

political environment has become more accepting of

far-right views, she has tacked back to the right. There is no real proof that

the act of governing is moderating Meloni; since mid-2024, evidence has piled

up that her centrist shift was merely tactical. European liberal democrats

should give up longing that, through flattery and inclusion, they can use

far-right figures to mitigate Trump’s attacks on Europe. Instead, they must

stress to far-right leaders the high cost of turning their backs on Europe—and

the unlikelihood that Trump can prove a reliable ally.

Center of Attention

Over ten years in Italy’s political opposition, Meloni

rose to prominence as a staunch skeptic of further European integration,

pushing for Italy’s exit from the eurozone and lambasting the EU bureaucracy in

Brussels. Soon after she became prime minister, she appeared to do

an about-face, backing Ukraine’s bid to join the EU and sustaining Italy’s

military aid to Ukraine. She even seemed to shed her Euroskepticism,

establishing strong personal ties with the president of the European

Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, and refraining from blocking EU decisions on

issues such as sanctions against Russia, aid to Ukraine, or added funding for

the bloc’s budget.

Many who had fretted

over her campaign warmed to her. U.S. President Joe Biden publicly praised

Meloni for her commitment to the transatlantic relationship after their first

bilateral meeting in July 2023, and von der Leyen repeatedly traveled with her

on high-profile trips to Tunisia aimed at curbing irregular migration from

Africa.

In policy circles,

many Europeans began to see Meloni as a model for how the far right might be

tamed. As far-right parties gained traction in Austria, France, Germany,

Romania, Spain, and beyond in recent years, more traditional leaders have

questioned whether it is wise even to try to keep them out of government. A

lesson seemed to emerge in Italy, where the center-right formed a governing

coalition with the far right in 2022: rather than mount an all-out battle to

keep far-right parties from power, the thinking went, European center-right

parties should work with those groups and in the process encourage them to

moderate. Center-right parties in Belgium, Croatia, Finland, the Netherlands,

and Sweden followed the Italian example.

But European

moderates were far too quick to make Meloni a happy example. Meloni always

pursued a nativist and socially conservative domestic agenda: in 2023, for

instance, her government issued directives to local authorities not to register

the birth of children to same-sex couples. Her adoption of a more centrist

foreign policy did not show that tackling the complexities of government leads

to moderation. It was the shield behind which she pursued more radical

positions at home.

Turn Coat

It now seems clear

that rather than arising from a change of heart, Meloni’s early pro-European

maneuvers were intended to neutralize criticism. Less than two years after she

took office, her policies began creeping rightward again—at first, in the domestic

sphere. Meloni attempted to increase her control over Italy’s judiciary,

lambasting the courts as political for hobbling her ability to offshore

refugees to Albania. Her government sought to intimidate critical journalists

and moved to replace top officials at Italy’s public broadcaster RAI, earning a

public reprimand from the European Commission for restricting the media’s

independence. And in late 2023, Meloni’s team proposed a reform of the Italian

constitution to concentrate more power in the prime minister’s hands.

Gradually, the prime

minister also began to pivot back toward the right on European issues and on

foreign policy. When Italy took over the G-7 presidency in January 2024, for

instance, it insisted on diluting or removing language supporting LGBTQ and abortion

rights from the G-7 leaders’ final communiqué. Trump’s November 2024 election

made the rightward shift easier. Last month, Meloni praised U.S. Vice President

JD Vance when he denounced the “weakness” of Europe at the Munich Security

Conference. Then, in an online address to the U.S. Conservative Political

Action Conference (CPAC), she lashed out at the mainstream U.S. media, “woke”

ideology, and a globalist elite.

Nowhere is Meloni’s

gradual reversal more obvious than on Ukraine policy. Her 2022 support for

Ukraine gained her the respect of her more moderate European peers as well as

policymakers in the Biden administration. But once she secured that

credibility, she began a distinctively incremental, nonconfrontational pivot to

the right. Since Trump’s return to office, when possible, she has avoided

talking about Ukraine altogether. When she has to, her

tone is studied: in her CPAC speech, while addressing Ukraine’s need for

security guarantees, Meloni omitted any mention of Ukrainian President

Volodymyr Zelensky, Ukraine’s territorial integrity, or Russia’s role as the

war’s instigator. In March, for the first time, her party abstained on a

European Parliament resolution in support of Kyiv. She has criticized the idea

of a “coalition of the willing” to defend Ukraine and rejected the notion of

deploying Italian troops in the event of a durable cease-fire unless such a

mission is mandated by the UN Security Council, where Russia and the United

States have veto power.

This slow walk

rightward may escape the notice of those accustomed to bombast from the far

right. But it is a considered strategy: after taking each step, Meloni observes

whether it has prompted pushback from her European peers, and

takes the next one only if circumstances allow. She has not made any moves so abrupt as to trigger alarm bells, but the direction of

travel is now clear.

Better Together

Meloni’s political shift

has also revealed that the more right-wing politicians take office, the more

strength and freedom they afford to one another. In 2023, Meloni had only one

far-right peer in Europe: Hungary’s right-wing prime minister, Viktor Orban.

Today, eight European governments include far-right parties, and two more—the

Czech Republic and Romania—could gain far-right participants this year. In the

2024 European Parliament election, the far-right group of parties to which

Meloni belongs won more seats than either the liberal or Green

faction did.

Meloni no longer has to pretend to be pro-European. Much like Orban, however,

she no longer advocates that Italy leave the EU or ditch the euro. Meloni knows

that Italy benefits enormously from EU membership and that its fiscal

predicament is fragile, given its monstrous public debt. Of the more than $800

billion in post-pandemic recovery funding allocated by the EU, Italy got a

whopping $220 billion. So the prime minister chooses

stances that are less disruptive: after last summer’s European elections, she

voted against Antonio Costa, a social democrat, for president of the European

Council and Kaja Kallas, a liberal, as the European Commission’s top diplomat.

She abstained from approving von der Leyen’s nomination as the European

Commission’s president, and her party went on to vote against von der Leyen’s

successful confirmation.

Meloni knew that her

opposition would not block or even delay the EU from reelecting its leadership.

Without causing any real damage, the far-right Italian leader felt confident

enough to begin revealing her Euroskeptic instincts again. In an appearance before

the Italian Parliament in March, Meloni lashed out specifically against the

vision of European integration advanced by Altiero Spinelli, an EU founding

father.

Like Orban, on issues

where her country can reap direct benefits from the EU, such as establishing

collective European funds to induce North African leaders to curb migration,

Meloni is all in. When it comes to furthering European integration, however, she

now embraces changing the bloc from within through

so-called bureaucratic simplification, a process she believes ought to include

fewer regulations, the return of power to member states, and the adoption of

fewer progressive laws, notably on climate change. She has expressed doubts

about the EU’s plans to coordinate Europe’s defense and, in scathing terms,

pooh-poohed French President Emmanuel Macron’s efforts to discuss a potential

collective European nuclear deterrent.

Right of Refusal

The centrists who

rushed to celebrate Meloni’s initial move toward the center should have been

more skeptical from the start. Populist leaders tend to reveal their true

colors gradually. In 2000, when Vladimir Putin was elected Russia’s president,

Western leaders applauded his purported embrace of modernization, although his

ruthlessness, revisionism, and authoritarianism were already on full display in

Chechnya. In the mid-2010s, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan masterfully

dispelled early concerns about his Islamist roots by inaugurating his rule with

a wave of democratic reforms. Shifting gradually towards the extreme—and

pushing more radical policies on the domestic front first—is smart because it

doesn’t set off alarm bells globally. So long as there are no abrupt changes in

a country’s strategic posture, most of what happens at home flies below the

international radar.

If right-wing parties

embrace gradualism, they can also trick their country’s center-right

politicians into believing that they have more power over their hard-line compatriots than they really do. Centrists tend

to believe that they can educate the far right into moderation. But with the

possible exceptions of Finland and Sweden, recent European history shows that

when the center-right starts cooperating with the far right, the far right ends

up dominating. This is what has happened in Italy. After the center-right, long

the dominant force on Italy’s right wing, normalized the far-right fringe’s

participation in the political system, that fringe’s successor—Meloni’s

party—came to rule the Italian right. The same process has been accomplished or

is now happening in Austria, France, and the Netherlands.

Like other far-right

leaders in Europe, Meloni would genuinely like to see the United States and

Europe stick together. She believes the two entities comprise the core of a

white, Christian West that can grow stronger if the far right consolidates

power. There are huge contradictions within this worldview, the so-called

“sovereigntist international” ideology, as nationalists often struggle to

cooperate and end up damaging one another’s interests—an effect already on

display as Trump begins his presidency.

In his second term,

Trump intends not to ignore Europe but to actively undermine it. He has made it

obvious that Europe can no longer depend on a U.S. security umbrella and argued

that European countries should spend as much as 5 percent of their GDP on defense—substantially

more than the 3.4 percent the United States itself spends. Although the average

European country’s defense spending has increased to just over 2 percent of

GDP, Italy remains a laggard, spending only 1.5 percent. Trump characterizes

the EU as a mechanism for ripping off the United States and has already begun

imposing some heavy tariffs on EU products.

Around a third of the

EU’s trade surplus with the United States is generated by Italy, so Trump’s

tariffs will harm Italy disproportionately. When that issue arises, Meloni has

shown visible discomfort.In

short, no matter how much ideological affinity Meloni and Trump might have, the

MAGA movement will damage all European countries, Italy included. In a

transactional world order in which nationalism prevails, small- to medium-size

states—in other words, European states, if they are divided—will

be among the first to suffer. Politics draws far-right parties across the

Atlantic together, but policy will force them apart.

On issues such as

trade and regulating technology, far-right governments even risk becoming

Trojan horses in the EU. By slowing or blocking policies aimed at making Europe

a stronger collective actor, they serve Trump’s desire to see Europe weak and

divided. In recent years, far-right governments have enjoyed substantial

freedom to pick and choose which pro- and anti-European initiatives they back.

But as Trump seeks to undermine Europe’s security and economy, far-right

European parties will have less space to dwell in ambiguity. Their leaders may

have to choose between Europe and Trump.

Yet pro-European

forces cannot afford to sit and watch or, worse, try to court far-right figures

such as Meloni as potential “Trump whisperers.” Rather than attempt to seduce

far-right leaders, liberal democrats in Europe should work to reveal the contradictions

in these leaders’ politics. As far-right populist leaders proudly purport to

represent the people, European moderates must point out that there is nothing

patriotic about their support for Trump and his drive to undermine Europe’s

security and prosperity. Only by exposing these inconsistencies—and

highlighting the steep costs, in the Trump era, of disrupting Europe’s

cohesion—can liberal democrats protect Europeans from the forces that seek to

subjugate them.

For updates click hompage here