By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The Hashemite Sherif Hussein

As we have

seen, British policymakers have attracted the notion of an Arab Caliphate

but were also deeply suspicious of any pan-Islamic iteration thereof. They

preferred that an Arab Caliph is a spiritual, rather than a temporal head of

Islam. The idea of a Caliphate as related to the Sherifian revolt remained

part of British policy through 1917.

On 16 November 1916 conference was held

in Rabegh where it was decided to

defend Rabegh, since it was seen as the key to

the route to Mecca on one hand and the base for the three Arab armies’

operations on the other. However when in December the newly created War Cabinet

decided to delegate the responsibility for sending a brigade to Sir Reginald

Wingate, the latter, although he had been the most ardent advocate of the

scheme, promptly shifted it onto Hussein, who in the meantime had been

proclaimed ‘King of the Arab Nation’, his precarious position notwithstanding.

By the middle of January 1917, it was evident that Hussein would not permit

British troops to land in the Hijaz. This proved to Wingate’s satisfaction

that, if the Arab revolt collapsed, the blame lay firmly on Hussein’s

shoulders.

Less mentioned, Ibn Saud was another

player in the Arabian Peninsula that enjoyed the support of the British. He was

gradually assuming control of the central and eastern provinces of the

peninsula with encouragement and support from the Anglo-India Office. The

latter was mindful of the need to preserve and safeguard routes to India, and

had been looking to the possibility of air routes being opened up between

Britain and India. It also was crucial to British interests that the whole of

the peninsula, not just the Hejaz on the western boundary of the peninsula,

should be friendly to the British.

The ‘Arab’ and the ‘Jewish’ question

On 1 September 1916, a French mission

arrived at Alexandria on its way to the Hijaz. It was headed by Colonel

Edouard Brémond, according to T.E. Lawrence ‘a

practicing light in native warfare’ who had been ‘a success .in French

Africa’.¹ However, it was not as a soldier that Brémond would

establish a reputation in the Hijaz. He did not conceal from his British

interlocutors that Hussein’s revolt should not grow into something bigger than

the local affair that it was. Cyril Wilson reported to Wingate on 24 October

that Brémond believed that ‘the longer the Arabs take

to capture Medina the better for Great Britain and France owing to the Syrian

question probably then becoming acute’.² At that moment, there was naturally

not the slightest chance that Hussein’s forces would capture Medina. The

chances were far greater that Britain and France would have to intervene

militarily to prop up Hussein’s tottering regime. Regarding the Rabegh question, Brémond was

in favor of sending a Franco–British force. According to Lawrence, however,

this was not as a means to save the sheriff’s revolt, but because the

landing of Christian troops would make Husayn’s position untenable in

Muslim eyes. In the same memorandum that Murray and Robertson so eagerly seized

on to torpedo the plans to send troops to Rabegh,

Lawrence also observed that Brémond considered

it vital that ‘the Arabs must not take Medina. This can be assured if an Allied

force landed at Rabegh. The tribal contingents

will go home, and we will be the sole bulwark of the Sherif in Mecca. At the end of the war, we

give him Medina as his reward.’³

T.E. Lawrence found a sympathetic ear for

his observations with Sir Henry McMahon, Sir Archibald Murray, and Wingate.

Each of them approached the home authorities on the matter. McMahon wrote to

Lord Hardinge that Brémond had

confided to Lawrence that the French object with the brigade ‘was to thus

disintegrate Arab effort, as they by no means wished to see them turn the Turks

out of Medina any sooner than could be avoided […] It is of course always the

old question of Syria’.⁴ Murray for his part warned Sir William Robertson that

the French attitude towards Hussein’s revolt was based on the ‘fear that if the

Sherif is successful in turning the Turks out of the Hijaz they will find that

the Arabs pro- pose to operate in Syria. This would not suit them.’⁵ Wingate

wired to the Foreign Office that the French worried about Hussein’s possible

capture of Medina ‘given their future Syrian policy’. The occupation of Medina

would lead to the ‘active support of all Arab tribes in the Syrian hinterland

who have sworn to rise in Shereef’s favor immediately Medina is in his

hands’.⁶ These telegrams, reports, and letters, however, did not initiate a

policy revision concerning French ambitions in Syria. The machinations of the

head of the French mission in the Hijaz were completely irrelevant in view of

the supreme aim of preserving cordial relations with France. Lawrence’s

observation that Brémond favored a landing

at Rabegh to discredit Hussein was

completely ignored during the meeting of the War Committee on 20 November,

where his report and person were extensively discussed. Lawrence’s remarks

on Brémond were moreover deleted from the

report that George Clerk compiled at the request of the War Committee for the

benefit of the French government,⁷ not only out of consideration for French

feelings, but also, as Clerk minuted on

Wingate’s telegram the next day, because ‘we have little evidence to support

the theory that the French do not want the Sherif to take Medina, I

find it hard to credit’.⁸ The source of these messages was, moreover,

considered suspect. Sykes’s reaction to a report by Wilson was typical. Wilson

related that a member of the British mission at Jedda had been informed that

during a conversation between members of the French mission and Rashid Rida,

the latter had told the French that ‘everybody in Egypt loathes the British and

how overjoyed the Syrians were at the French joining the Arab movement as their

Friend, etc.’ This made Sykes burst out in anger. In a letter

to Hardinge he railed against the type of Englishmen who permitted the

French ally to be spied on. This he blamed on the fact that ‘our people in

Egypt, still think that there is a chance of getting Syria’. It was high time

they realized that to the Arab cause ‘cooperation between French and British is

more important than Rabegh’. Sykes suggested

that ‘a very definite instruction should go to the sirdar urging him to see to

frank and trustful cooperation among the officers of the two missions’. Wingate

was accordingly informed that ‘it would seem desirable to impress upon your

subordinates the need for the most loyal cooperation with the French whom His

Majesty’s Government do not suspect of ulterior designs in the Hijaz’.⁹

This was the end of the affair as far as the Foreign Office

was concerned. After this reprimand, Wingate and Wilson did not return to this

subject other than Wingate transmitting Wilson’s assurance that he was ‘well

aware of the necessity for loyal cooperation and that this policy will be

scrupulously adhered to by me’.¹⁰ A report by Lawrence on a conversation

between Faisal and Brémond, however, provided a

good opportunity to make a fresh at- tempt to open the home authorities’ eyes

to the problem. Brémond had observed to

Faisal that he should not forget that ‘the firmness and strength of the present

bonds between the allies did not blind them to the knowledge that these

alliances were only temporary and that between England and France, England and

Russia, lay such deep and rooted seeds of discord that no permanent friendship

could be looked for’. Who exactly, so Wingate wrote to Balfour, was

jeopardizing the all important British–French

cooperation? The people in Cairo, who ‘loyally observed the policy of “hands

off” in matters Syrian’, and scrupulously saw to it that ‘our policy and that

of the French are, and will remain closely coordinated’, or Colonel Brémond, who ‘in conversation with the Arab leaders, has

not scrupled to convey to them a contrary impression’? This time the Cairo

authorities did not confine themselves to dispatching letters. On the

suggestion of Wilson it was decided to send Captain George Lloyd, MP, to

London. Lloyd, who had served in the Hijaz in the previous months, was

entrusted with the task to explain that Brémond and

his staff were responsible for the recurring problems in the Hijaz, and that

more was at stake than a purely local affair.

The Foreign Office

again refused to take the matter very seriously.

Although Hardinge was now prepared to admit that Brémond had shown himself to be ‘unreliable and

untrustful’, the forthcoming mission by Sykes and Georges-Picot would soon set

matters right, the more so as Picot had told Sir Ronald Graham that he intended

to assume control of affairs in the Hijaz. The instructions of Sykes and Georges-Picot constituted

a faithful reflection of the Foreign Office’s policy towards the Middle East,

with which Sir Mark completely identified. Everything turned on cordial

relations between France and Britain. British diplomacy should spare no effort

to accommodate French susceptibilities, whether these were justified or not.

This was the reasoning be- hind McMahon’s convoluted formulations in his

letters to Hussein in the autumn of 1915. This also explained the procedure of

first coming to an agreement with France before the negotiations with Hussein

could be finalized. This did not mean that Grey, Sykes and Foreign Office

officials were blind to the problems that this policy entailed, but these

counted for little compared to the all important objective

of good relations with France. Bal- four’s minute on Wingate’s dispatch

on Brémond’s machinations, however,

indicated that he was less attached to this orthodoxy: ‘I think if the French

intrigues go on in the Hedjaz we shall have to take a strong line. They may

find us interfering in Syria if they insist on interfering in Arabia.’¹¹

‘A Whole Crowd Of Weeds Growing Around Us’

Balfour’s minute

constituted a first indication that British Middle East policy would change

after Grey had left the Foreign Office. This was for the greater part due to

the increasing meddling in foreign affairs by members of the War Cabinet, Prime

Minister Lloyd George in particular, as well as the establishment of the

interdepartmental Middle East Committee, subsequently the Eastern Committee,

chaired by Curzon.¹² Balfour dominated British foreign policy-making to a far

lesser extent than Grey had done in his days. In the early spring of 1917,

matters still hung in the balance. For the time being Brémond could

continue to make a nuisance of himself in the Hijaz. The Failure of

the ‘Projet d’Arrangement’

Sykes’s arrival in Egypt heralded the reversal of the Foreign Office’s attitude

towards the complaints from Cairo about the French mission. From that moment on

these were no longer treated as utterances by biased men on the spot who tried

to blow up incidents to further their own Syrian ambitions. On 8 May 1917,

Sykes – who at the beginning of March had already written to Wingate that he

had ‘seen the George Lloyd correspondence and George Lloyd, truly Bremond’s

performances have been disgusting’¹³ – telegraphed to Graham that after a

careful investigation he had reached the conclusion that ‘the sooner French

Military Mission is removed from Hedjaz the better’. The ‘deliberately perverse

attitude and policy’ on the part of Brémond and

his staff constituted the main obstacle in the way of Sir Mark’s attempts to

improve relations between the French and the Arabs. These men

were: Without exception anti-Arab and only serve to pro- mote

dissension […] Their line is to crab British operations to Arabs, throw cold

water on all Arab actions and make light of the King to both. They do not

attempt to disguise that they desire Arab failure. Without assistance I do not

believe Picot will be strong enough to carry the day […] I suggest there- fore

that His Majesty’s Government make representations that French military mission

in Hedjaz has now fulfilled its purpose […] and that it should be brought to an

end.

Sir Mark’s

recommendation was not ignored by the Foreign Office. Four days later, Lord

Bertie was instructed to impress on the French government that the mission to

the Hijaz be withdrawn in view of the open enmity Brémond and

his staff displayed towards the Arab cause, which ‘cannot but prejudice Allied

relations and policy in the Hedjaz and may even affect whole future of French

relations with the Arabs’.¹⁴ It took almost a fortnight before Bertie received

a reply. In the meantime, the Foreign Office was informed of the instructions

given to Si Mustapha Cherchali, an Algerian

notable who was to leave for the Hijaz on a mission principally concerned with

‘purely Muslim affairs’. These confirmed that more was at stake than some local

incidents. Besides instructions concerning the mission’s primary objective,

there were instructions of a more general political nature. These were ‘of much

greater importance and raise whole question of Franco–British relations in

Arabia’, as they made clear that ‘French now de- sire to limit their

recognition of our special position in Arabia to an admission of our

preponderant commercial interests’:

France, in agreement

with England, desires only to maintain on the one hand the independence of

the Sherif, and on the other hand the integrity of his possessions. We

feel as do our Allies, that no European Power should exercise a dominant or

even preponderating influence in the holy places of Islam and we are resolved

not to intervene in political questions affecting the Arabian Peninsula. We

feel, moreover, in full accord with our Allies, that no European government

should acquire a new foothold (établissement) in

Arabia. While feeling that no Power should obtain either new territory or

political prestige in Arabia, the French government recognize that the

proximity of Egypt and the Persian Gulf creates a situation in favor of the

commercial interests of the English Allies which you should bear in mind.

It was, in

particular, this last sentence that Graham found unacceptable. If the French

position was not challenged, then the door was wide open to,

as Hardinge had formulated it in November 1916, ‘the reversal of our

policy of the last 100 years which has aimed at the exclusion of foreign

influence on the shores of the Red Sea’. According to Sir Ronald: We

can admit that no European Power should exercise a predominant influence in the

holy places. But the French note goes much further than this in laying down

that no Power is to obtain new territory or political prestige in Arabia and in

limiting French recognition of our special position there to commercial

interests. Hitherto the French have always recognized our special political

position […] I fear we must conclude that the French desire to go back on this

attitude and to claim an equality of political position with us in Arabia –

when they had no position at all and owe any improvement that they have

latterly achieved in this respect entirely to our help and influence. Such a

submission, which is a poor return for our rapport, must be strongly

resisted. Graham proposed to consult Wingate on Cherchali’s instructions, as well as the most

appropriate reaction. Cecil agreed but cautioned that the reply had to be

formulated with the greatest care, as ‘it will be a definite statement of

Franco–British relations in Arabia’.¹⁵ Wingate’s reaction to Cherchali’s instructions was along the same lines as

Graham’s minute. He also believed that ‘we must insist on formal recognition by

French government of our preponderant position in Arabia’. The French

apparently threatened to forget that ‘only by our support military as well as

diplomatic, can they expect to realize their present aims in Near East and, in

particular, that our continued good offices with King Hussein and Syrian

Moslems will be essential to an amicable settlement of Syrian question’.

Sykes, for his part,

proposed his customary solution, to let Georges-Picot and him work out an

arrangement. Lancelot Oliphant and Graham were not sure. According to Oliphant,

Sykes, in any case, should ‘cease to be a free lancer’,

and as far as Picot was concerned, he was ‘far from easy in my own mind as to

the extent that M. Picot speaks for his own government (or even for himself) in

talking to Sir M. Sykes’. Sir Ronald doubted ‘whether M. Picot exerts such a

beneficent influence in the French government as Sir M. Sykes represents’.

However that may be, there was ‘little prospect of their doing anything more

where they are at present’. Sykes was accordingly instructed on 5 June ‘to

proceed to London without stop- ping in Paris’. Two days later, the French

government was requested also to recall Georges-Picot for further

consultations.¹⁶ In a dispatch to Balfour, dated 11 June 1917, Wingate returned

to the subject. The Sykes–Picot agreement was ‘unsatisfactory and inadequate in

one, to my mind, all- important point of strategy’. It had not settled the

British position in the Red Sea, while ‘our position here must be unassailable

or we run the risk of creating a “Baghdad Railway” question in the Red Sea the

development of which may gravely impair our relations with France and Italy and

even menace the security of our imperial system’. Wingate’s remedy had two

aspects, which he had most succinctly formulated in a telegram sent the day

before: Our policy should be to obtain French recognition of our

predominant position in Arabian Peninsula as a preliminary to concluding a

treaty with King Hussein which, whilst not impairing his independence vis-à-

vis of Moslem world, will prevent any foreign power under guise of pilgrim

interest from acquiring rights and privileges detrimental to our special

political and economic interests in the Hedjaz.¹⁷

According to Sir Reginald,

Hussein at the end of the day was no more than one of the many chiefs on the

Arabian Peninsula. It was ‘very necessary to make a clear distinction between

practical politics and propaganda’. He, therefore, did not see, ‘in view of the

fact that we have created, directed and financed the Arab revolt’, why it would

not be possible to conclude a treaty like the one he pro- posed. Naturally, ‘we

must be careful to create and pre- serve, for as long as may be necessary, the

facade of an independent Arab Empire’, as ‘an Arab caliph or imam buried away

in the sands of the Arabian desert (would) appeal to Moslems nowhere’, but this

did not imply that with the king no agreement could be signed ‘differing little

from those we have made with the Trucial Chiefs’.¹⁸

To Sykes, however, it

was unthinkable that Hussein would be treated on the same footing as the other

rulers on the Arabian Peninsula. He argued that ‘if there is to be a King of

Hejaz he must be independent of all foreign control otherwise he has no value

or influence and is only a danger’. When Britain would ‘reduce him to the

position of a feudatory chief in our pay, then we not only destroy the Arab

movement but we throw the whole control of the Moslem world into the hands of

the Turks, the pan-islamists, the seditionists and

the Egyptian revolutionary nationalists’.¹⁹ Graham voiced the same argument in

less alarmist terms in a minute on a further telegram by Wingate, in which the

latter again urged a revision of the Sykes–Picot agreement in order ‘to eliminate

present southern boundary of Area B’.

Sir Ronald believed

that it was not in the interest of Great Britain ‘to assume publicly anything

in the nature of a sort of British Protectorate over the holy places and the

Shereef, who may well be caliph some day. To do so

would destroy or at any rate weaken his position and land us in an embarrassing

situation in the future.’ The revision advocated by Wingate was moreover

completely unnecessary, since ‘our presence in Egypt close by, the great number

of British native pilgrims as compared with those of any other State and our

intimate existing relations with the Sherif and his family –

financial and political – render it inevitable that we should enjoy a special

position with him and in the Hedjaz’. Britain’s policy should be to get the

other powers to give an undertaking that they would refrain from intervening in

the internal affairs of the Hijaz. Hardinge concurred. Provided that

‘no foreign Power is allowed to obtain a preponderating influence in the Hedjaz

we may regard with serenity the fact that it is not our protectorate […] We

shall in the end by force of circumstances obtain a very strong position in the

Hedjaz as the main support of the Sheriff’.²⁰ After Harold Nicolson had

completed a first draft for a reply to the French memorandum with Cherchali’s instructions on 14 June, the question was

referred to the Mesopotamian Administration Committee (MAC).²¹ This committee

had been established by the War Cabinet on 16 March 1917. Besides Curzon as

chairman and Sykes as secretary, it consisted of Lord Alfred Milner, Hardinge,

Sir Arthur Hirtzel, Sir Thomas Holderness, Graham and Clerk. Sir Henry

McMahon also became a member. The MAC had initially only dealt with the

organization of the administration of the occupied territories in Mesopotamia,

but it had soon been felt that it should have greater authority. The occasion

had been Wingate’s dispatch of 11 June. On 7 July, Sir Eric Drummond wrote to

Sir Maurice Hankey that Balfour wanted an extension of the MAC’s powers, ‘so as

to enable it to deal with other questions such as Arabia, Hedjaz, etc. The idea

is I believe to form a Committee of which the S. of S. for F.A. and the S. of

S. for India will be permanent members in order to decide all Middle Eastern

matters. It is a good scheme.’²² The War Cabinet accepted Balfour’s proposal a

week later. At this meeting, Milner relinquished his seat, and the DMI was

appointed as the military representative on the committee.²³ It was also

decided to change the committee’s name into the Middle East Committee (MEC). On

23 August, Hardinge submitted to Cecil a new draft reply. It was in

line with a memorandum written by Curzon. As ‘the matter is urgent, and has

already been subject to much delay’, Hardinge proposed to settle the

question right away. Cecil, however, hesitated to ‘authorise this

draft in the absence of Mr Balfour’, but it

was finally approved, with some minor revisions, on 28 August.²⁴

Sykes did not like

the approved reply at all. He complained to Graham that: It is very

ridiculous to adopt a 1960 A.D. policy in India and a 1887 A.D. policy in the

Red Sea. We certainly do not require any rights in HEJAZ over and above those to

be enjoyed by our allies. The HEJAZ must be a completely independent state if

we are to defeat the Turks. It will never be independent if we have a special

position there, and the Sharif will always be our dependant and therefore out of the running for the

caliphate; which is contrary to our interests because it fastens the caliphate

for good and all onto the Turks. It was his opinion that the best

thing would be, as always, to let Picot and him settle the matter. But Clerk,

who substituted for Graham, was not entirely convinced of this. It was one

thing to show consideration for French ambitions, but it was quite another to

give up British interests without getting anything in

return: Throughout these Asia Minor and Arabian negotiations it has

seemed to me that Sir Mark Sykes, while quite rightly endeavoring to reach an

understanding with the French which shall be free from all suspicion and

misunderstanding, has gone to work on the wrong principle. He appears to think

that the way to get rid of suspicion is always to recognize what the other

party claims and to give up, when asked, our claims. For many years our

relations with Germany were run on those lines. My own belief is that the right

course is to be as accommodating as possible, and ready to recognize the legitimate

claims of other people, but to be both frank and tenacious about those things

which are held to be vitally necessary to the existence of the British Empire.

Hardinge fully

agreed. There was nothing in Sykes’s letter to modify the approved note, and

‘thanks to the Sykes– Picot agreement our position is already a bad one in

connection with Asiatic Turkey and Arabia, and for heaven’s sake let us not

make it even worse’.²⁵ The British memorandum on Cherchali’s instructions

was handed to Cambon on 29 August. Although Graham considered the French reply

of 18 September ‘not altogether clear’, British claims were recognized in

principle, and accordingly it ‘foreshadows an agreement which may prove

satisfactory’. Hardinge believed that ‘the note is on the whole

better than might have been expected’. His disparaging remark several weeks

before notwithstanding, Hardinge accepted Graham’s suggestion to send

Sykes to Paris in order ‘to draw up an agreement “ad referendum”’, be it with

‘definite instructions’. These were telegraphed to Bertie on 26 September. Sir

Mark was directed to draw up a draft agreement ‘respecting future status of the

Hejaz and Arabia’. The most important British desiderata in this agreement

were:

a. That

[it] is essential to obtain explicit recognition by France of British political

supremacy in Arabia as a whole with the exception of the Hedjaz.

b. That

the limits of the Hedjaz shall be defined.

c. That

within those limits Hedjaz shall be recognized as a sovereign, independent

State but that the existing arrangements for dealing with King Hussein and the

Arabs shall hold good for the duration of the war.

d. That

France on her part shall undertake to enter in no Agreement with the King or

Government of Hedjaz on any matter concerning the Arabian Peninsula or the Red

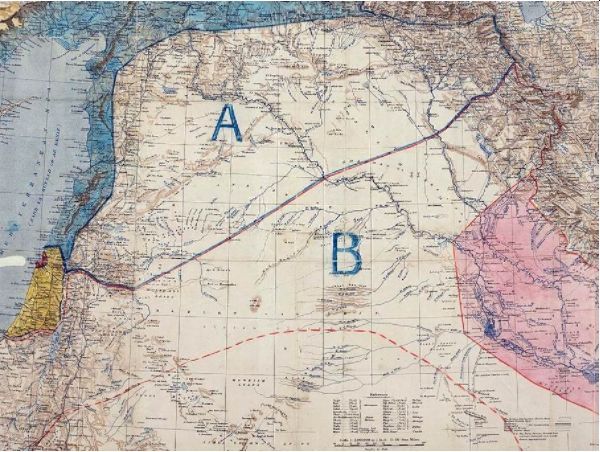

Area or Area B (Anglo– French Agreement of May 1916) without the knowledge and consent

of Great Britain.

e. That

Great Britain on her part shall undertake to enter into no Agreement with the

King or Government of Hedjaz on any matter concerning either the Blue Area or

Area A (Anglo–French Agreement of May 1916) without the knowledge and consent of

France.²⁶

Even though these instructions evidently reflected the

accursed spirit of ‘1887 A.D.’, within a week Sykes and Picot managed to

complete a draft agreement (Projet d’Arrangement) that, in the words of Clerk, ‘seems to cover

the instructions sent to M. Sykes pretty well’. The most important point was

that the French government were finally prepared explicitly to recognize

Britain’s special interests in the Arabian Peninsula, and confirmed its

intention ‘not to seek any political influence in these regions’. Hardinge

noted with satisfaction that the French were ‘ready to accept our political

supremacy in the Arabian Peninsula, with the exception of the Hedjaz’, which

was ‘a point gained’. Especially when one took into account that regarding the

Hijaz, ‘owing to the close connection of the holy places with Egypt, Aden and

Mesopotamia [there should] be no difficulty for us in acquiring and eventually

asserting a position of predominance there also’.²⁷ Apart from a few minor

points that needed modification, the desired supplement to the Sykes–Picot

agreement with respect to the Arabian Peninsula seemed finally to be within

reach. The French government, however, failed to ratify the draft agreement.

Although the Quai d’Orsay time and again confirmed that the Council of

Ministers could approve the arrangement any moment, they failed to do so. On 4

December, the Foreign Office replied to Wingate, after the latter had enquired

how matters stood, that ‘exchange of notes has not yet actually taken place,

but it is hoped to complete arrangement within the next fortnight’.²⁸ However,

this hope, too, was dashed.

1.T.E. Lawrence, Seven Pillars of

Wisdom: A Triumph (London, 1977: Penguin), p. 113; cf. also Général

E. Brémond, Le Hedjaz dans la guerre mondiale (Paris, 1931: Payot),

pp. 35–44, and Dan Eldar, ‘French policy towards Husayn, Sharif of

Mecca’, Middle Eastern Studies, 26 (1990), pp. 337–8.

2. Tel.

Wilson to Wingate, no. W. 394, 24 October 1916, Wingate Papers, box 141/3.

3. G.O.C.-in-C.,

Egypt to D.M.I, no. I.A. 2629, 17 November 1916, Cab 42/24/8; cf.

also Eldar, ‘French policy’, p. 339.

4. McMahon

to Hardinge, 21 November 1916, Hardinge Papers, vol. 27.

5. Murray to

Robertson, 28 November 1916, Add. Mss. 52462.

6. Tel. Wingate to

Grey, no. 29, 23 November 1916, FO 371/2776/236128.

7. See Grey to

Bertie, no. 779, 22 November 1916, FO 371/2776/232712.

8. Minute Clerk, 23

November 1916, FO 371/2776/ 236128.

9. Sykes

to Hardinge, 21 November 1916, minutes Clerk, 22 November 1916,

and Hardinge, not dated, and tel. Hardinge to Wingate, private,

24 November 1916, FO 371/2779/233854.

10. Tel. Wingate

to Hardinge, private, 27 November 1916, Wingate Papers, box 143/4.

11. Wingate to

Balfour, private, 11 February 1917, and minutes Hardinge, not dated,

Graham, 24 February 1917, and Balfour, not dated, FO 371/3044/40845.

12. See also Roberta

M. Warman, ‘The erosion of Foreign Office influence in the making of foreign

policy, 1916–1918’, The Historical Journal, 15/1 (1972), pp. 133–59.

13. Sykes to Wingate,

6 March 1917, Sykes Papers, box 2.

14. Sykes to Graham,

no. 23, in tel. Wingate to Balfour, no. 497, 8 May 1917, and tel. Balfour to

Bertie, no. 1243, 12 May 1917, FO 371/3051/93348.

15. French Embassy to

Foreign Office, 16 May 1917, reprinted in John Fisher, Curzon and British

Imperialism in the Middle East 1916–1919 (London, 1999: Frank Cass), pp.

313–16, tel. Balfour to Wingate, no. 540, 29 May 1917, and minutes Graham, 21

May 1917 and Cecil, not dated, FO 371/3056/100065.

16. Tel. Wingate to

Balfour, no. 583, 3 June 1917, minutes Oliphant, 4 June 1917, Graham, not

dated, tels Balfour to Wingate, no. 571, 5

June 1917, and Balfour to Bertie, no. 1521, 7 June 1917, FO 371/3056/110589.

17. Wingate to

Balfour, no. 127, 11 June 1917, FO 371/3054/125564, and tel. Wingate to

Balfour, no. 609, 10 June 1917, FO 371/3054/115603.

18. Wingate to

Balfour, no. 127, 11 June 1917, FO 371/3054/125564.

19. Minute Sykes, 22

June 1917, on tel. Wingate to Balfour, no. 609, 10 June 1917, Cab 21/60.

20. Tel. Wingate to

Balfour, no. 696, 3 July 1917, minutes Graham and Hardinge, not dated, FO

371/3056/131922.

21. See Nicolson,

‘Draft for a Note to the French ambassador’, 14 June 1917, FO 371/3056/132784.

22. Drummond to

Hankey, 7 July 1917, Cab 21/60.

23. Minutes War

Cabinet, 13 July 1917, Cab 23/3.

24.

Minutes Hardinge and Cecil, not dated, FO 371/3056/165801.

25. Sykes to Graham,

not dated, and Clerk to Hardinge, 28 August 1917, minute Hardinge,

not dated, FO 371/3044/168691.

26. Memorandum French

Embassy, 18 September 1917, minutes Graham and Hardinge, not dated, and

tel. Balfour to Bertie, no. 2387, 26 September 1917, FO 371/3056/181851.

27. Minutes Clerk, 8

October 1917, and Hardinge, not dated, on ‘Projet d’Arrangement’, 3 October 1917, FO 371/3056/191542.

28. Tel. Balfour to Wingate, no. 1152, 4 December

1917, FO 371/3056/227997

For updates click hompage here