By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The Making Of The Modern Middle East

Part Four

To know the context of what

follows start with the

overview here, and for reference list of personalities involved here.

While this subject has been researched

many times today it is generally accepted that British politicians sought the

means during wartime to limit long-term German threats to the Empire. This was

because the acquisition by Germany, through her control of Turkey, of political

and military control in Palestine and "Mesopotamia" would imperil the

communication through the Suez Canal, and would directly threaten the security

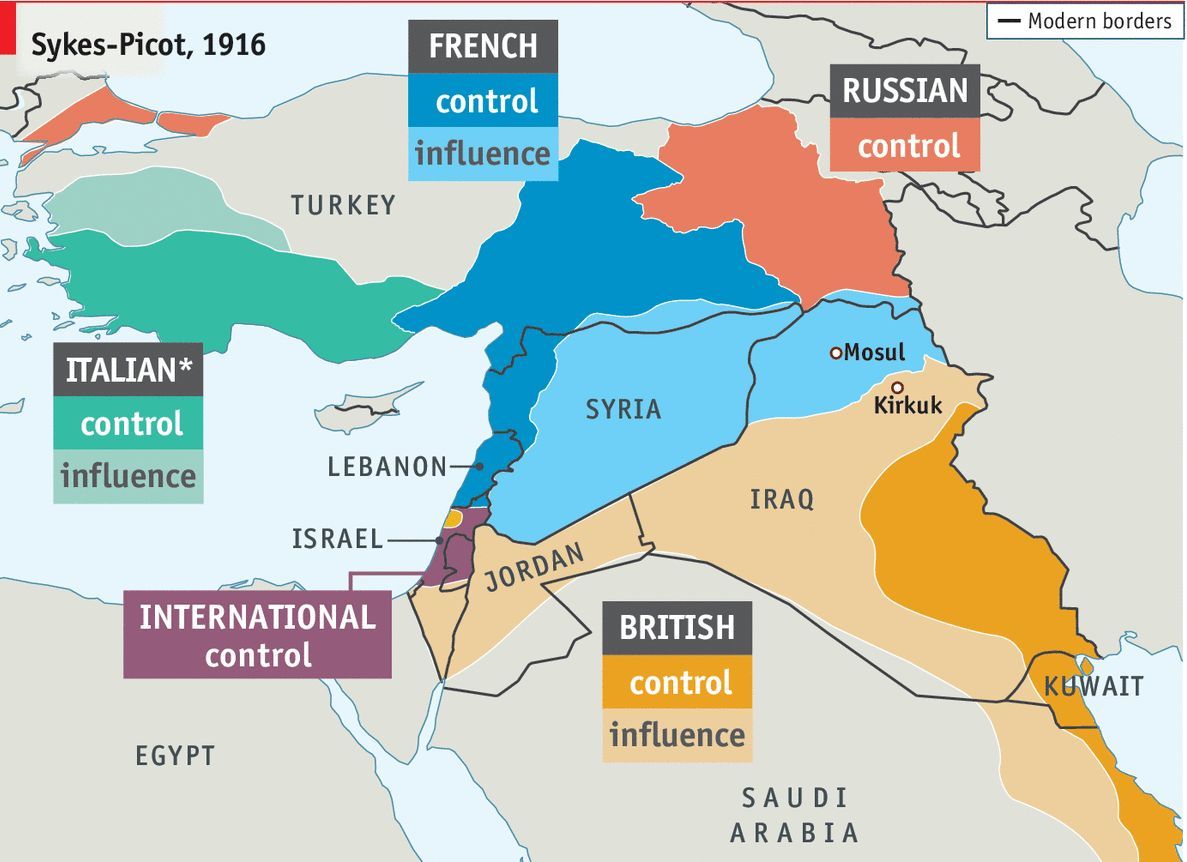

of Egypt and India.1 Although the Sykes-Picot Agreement had concluded with an

international Holy Land, neither

party was satisfied. If the War Office wanted to secure communication

between Great Britain and the East, they would first need to block residual

French claims to Palestine.2 And possible of greatest importance was the fact

that the British Petroleum pipeline moved through Palestine evident in their

anxiety to ensure that the oil from Iraq was able to flow freely to Haifa.3

Thus, Prime Minister David Lloyd, George intended to use British forces advancing on Gaza to

present the French with a fait accompli, the British occupation of Palestine

would constitute a strong claim to ownership.4

As we have seen, British policymakers have attracted the

notion of an Arab Caliphate but were also deeply suspicious of any pan-Islamic

iteration thereof. They preferred that an Arab Caliph is a spiritual, rather

than a temporal head of Islam. The idea of a Caliphate as related

to the Sharifian revolt remained

part of British policy through 1917.

On 16 November 1916 conference was held

in Rabegh where it was decided to

defend Rabegh, since it was seen as the key to

the route to Mecca on one hand and the base for the three Arab armies’

operations on the other. However when in December the newly created War Cabinet

decided to delegate the responsibility for sending a brigade to Sir Reginald

Wingate, the latter, although he had been the most ardent advocate of the

scheme, promptly shifted it onto Hussein, who in the meantime had been

proclaimed ‘King of the Arab Nation’, his precarious position notwithstanding.

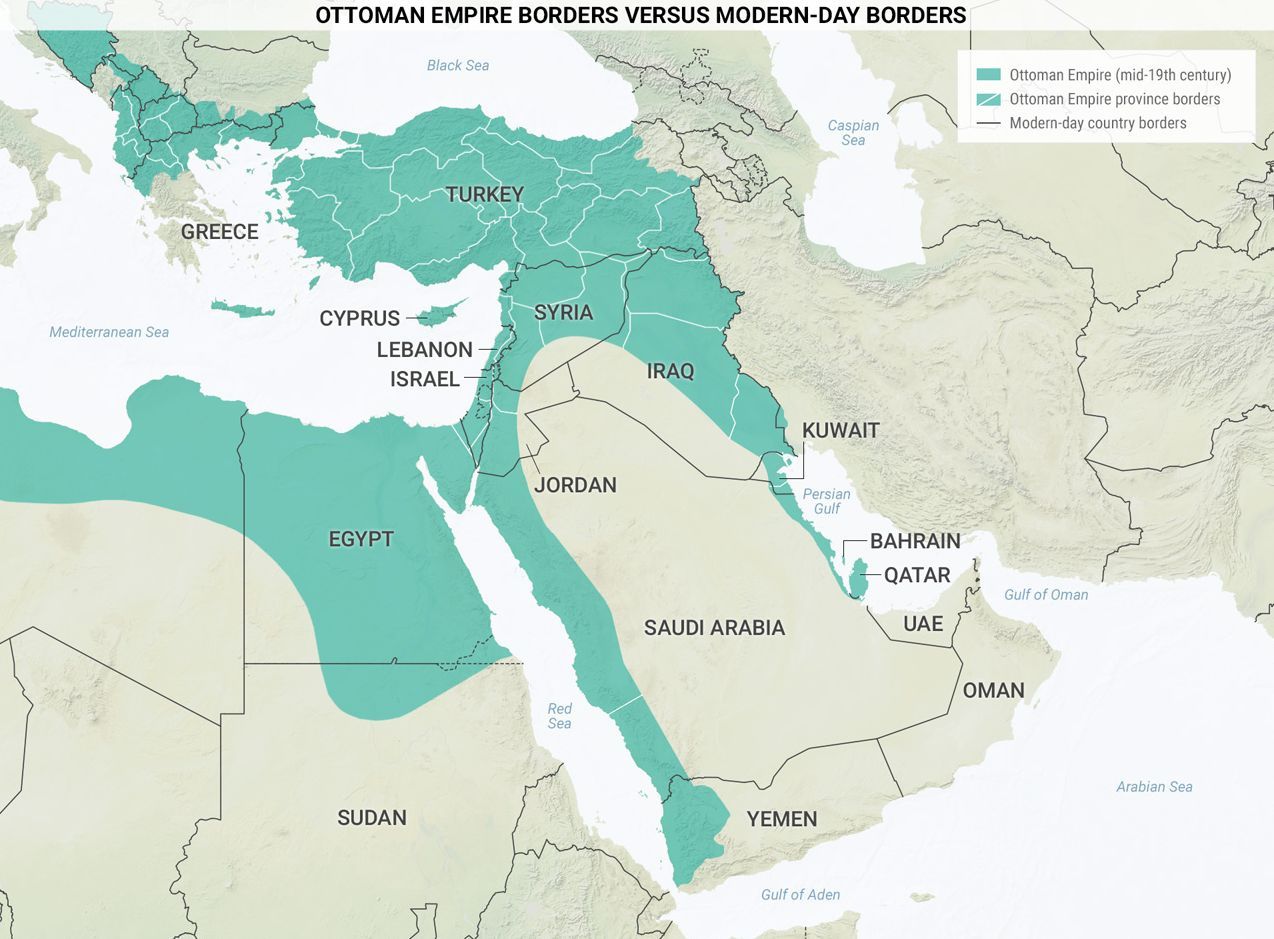

The Ottoman Empire ruled much of the

Arab World for four centuries. This included the region of the Hijaz, the jewel

of the empire, which encompasses Islam’s two holiest cities: Makkah and

Madinah. The Hijaz was traditionally ruled autonomously, with Ottoman imperial

assent, as mentioned above, by a succession of Arab Sharifs, members of

the Hashimite dynasty who claimed direct

descent from the prophet of Islam.

The discussions between the British and

the French who would control what followed the breakdown of the

Ottoman Empire in the Middle East would reach fever pitch during the Versailles deliberations.

Although its centennial is to come up

next, while even very few people are aware of the various aspects of the Treaty

of Versailles, one should add that there was also the Treaty of Saint-Germain

with Austria on September 10, 1919, the Treaty of Neuilly with Bulgaria on 27

November 1919, the Treaty of Trianon on June 4, 1920 with Hungary, and the

Treaty of Sevres with the Ottoman Empire on August 10, 1920, which subsequently

was superseded by the Treaty of Lausanne made on June 24, 1923 with the new Republic

of Turkey.

The Treaty of Sevres covered the

partitioning of the Ottoman Empire and determined the nature of the

post-war political entities that took its place. Following the initial meetings

in Paris in the spring and summer of 1919, the negotiations continued into 1920

with substantive meetings at the Conference of London (February 12-24) and

the San Remo Conference (April 19-26). It was the San Remo agreement and the

mandate policies that were applied to the newly created Arab countries in

Al Mashriq that replaced the Sykes-Picot

agreement. Nothing was left of the Sykes-Picot agreement except the initial

demarcation of Lebanon, Iraq, Transjordan, and Palestine borders.

For many Arabs who until then simple

felt themselves to be inhabitants of the Ottoman Empire, now broken in pieces,

a search for identity would ensue, once a search for survival had been

satiated.

Against the backdrop of soon-to-be

rising nationalist movements across the Middle East and an assertive Turkish

military and nationalist alliance sweeping away the final vestiges of Ottoman

rule, the wartime allies attempted to maintain political control by devising

and distributing a system of mandates for

administering the region.

At the end of WWI the history of the

making of the modern Middle East thus could be seen as the exercise of imperial

power, skilled at advancing its

interests over those of others.

The early twentieth century witnessed a

decline in Arab-Turkish relations due to the rising tide of nationalist

movements and radical regime change brought about by a revolution in the

empire. The Ottoman entry into the First World War on the side of the Central

Powers signaled the final turning point in Arab and Turkish relations. In 1916,

Sharif Hussein bin Ali, the then-Emir of Makkah, launched an armed rebellion,

commonly referred to as the

Arab Revolt, against the Ottoman Turks in alliance with Great Britain and

her allies under false promises of the establishment of an independent and

unified Arab kingdom after the war. With the post-war dissolution of the

Ottoman Empire, however, many Arabs found themselves divided into new states

under British and French domination, laying the foundations of many of today’s

crises in the Middle East. Indeed, the sense of betrayal felt by the Arabs has

influenced their views of the West ever since.

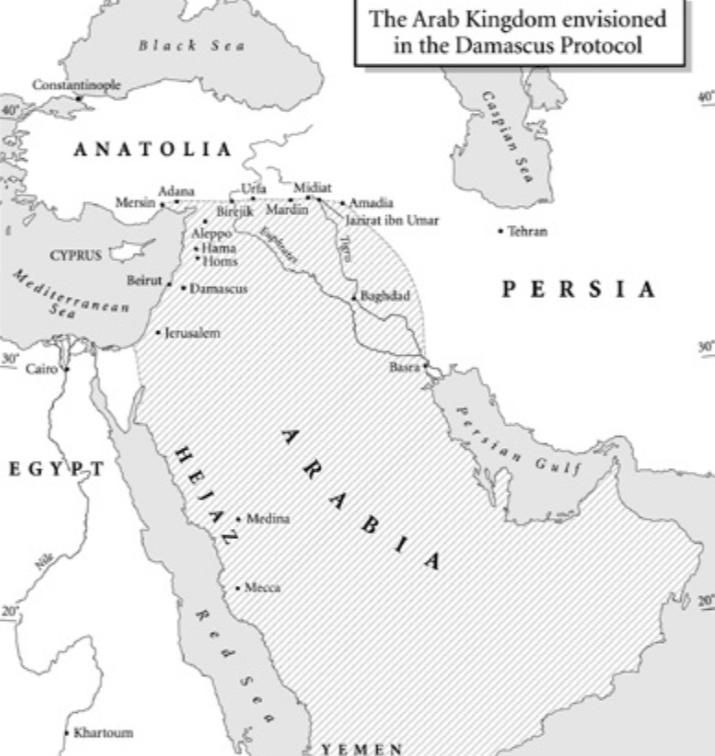

The Damascus Protocol was a document

given to Faisal bin Hussein on 23 May 1915 by the Arab secret societies

al-Fatat and al-'Ahd on his second visit to

Damascus during a mission to consult Turkish officials in Constantinople. The

secret societies declared they would support Faisal's father Hussein bin Ali's

revolt against the Ottoman Empire if the demands in the protocol were submitted

to the British. These demands, defining the territory of an independent Arab

state to be established in the Middle East that would encompass all of the

lands of Ottoman Western Asia south of the 37th parallel north, became the

basis of the Arab understanding.

This was followed by the correspondence list here.

For updates click hompage here