By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The Making Of The Modern Middle East

Part Five

To know the context of what

follows start with the

overview here, and for reference list of personalities involved here.

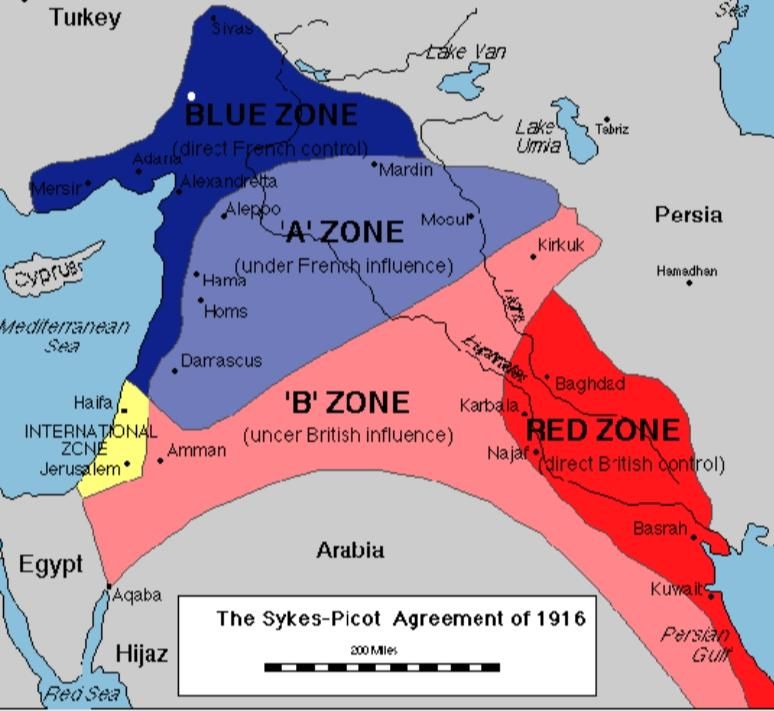

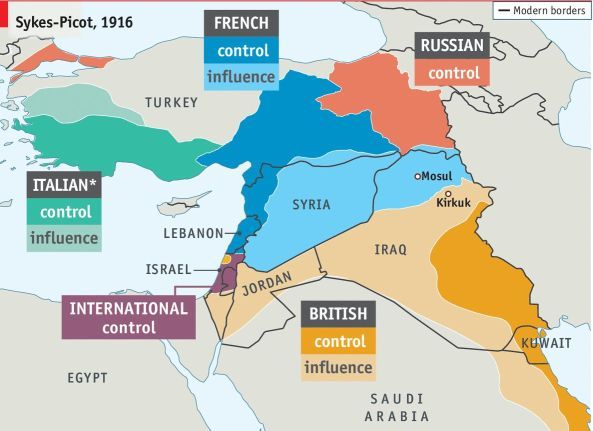

As we have seen the Sykes-Picot

negotiations of 1916, had agreed to cede most of greater Ottoman Syria to the

French zone of influence, although only the coastal area (i.e., today’s

Lebanon) was supposed to be under direct French rule, with the inland portions

under 'independent' Arab administration, which in practice meant Faisal

and crowned ‘King’ Hussein’s other sons. Theoretically, there was to be a kind

of border between the two zones stretching along a line drawn through Damascus,

Homs, Hama, and Aleppo, each allotted to the Arab side— though these cities

were still squarely in the French 'zone of influence.' But how was France to

exert predominance over areas now occupied by British troops? Complicating

these questions further was the Woodrow Wilson factor. Because of the possibly

decisive contribution of American troops to the collapse of German morale on

the Western front, along with the financial leverage U.S. banking institutions

now enjoyed vis-à-vis the Allies indebted to them, the American president was

believed to be nearly all-powerful on the eve of the peace talks that

would open in Paris in January.

Sykes-Picot is often

accused of having divided up the Arab world, but as we shall see Mark Sykes may

have believed that his actions had the best interests of the Arabs at heart. He

believed that, if properly encouraged, it would be possible to reawaken among

the Arabs memories of a vanished greatness and bring them closer to the

community of nations.

While the carnage at

Gallipoli mounted day by day, Sir Mark Sykes was dispatched by the War Office

to visit British commanders, diplomats and imperial officials throughout the

eastern theatre of war.

In India

Lord Hardinge, opined that ‘Sykes did not seem to be able to grasp the

fact that there are parts of Turkey unfit for representative institutions.’

During his long

return sea journey from India Sykes turned his ever-wandering attention to

Iraq, concerning which he composed a lengthy memorandum on the political and

military situation. However, in the second part of that memorandum entitled

‘Indian Muslims and the War’, his thoughts returned to the subject which had

long been the main preoccupation of both himself and his chief, Kitchener – the

ever-present danger of jihad. It was fear of militant Islam which had

underpinned his belief that Britain should cultivate those elements of the

religion he construed as ‘moderate’ and susceptible of being won over to the

Allied side; and now, having witnessed signs of anti-British nationalism among

the Muslims of India during his recent visit, he merged his visceral dislike of

‘westernized orientals’ with a conceptualization of the two

main tendencies which he believed he had detected in contemporary Islam.

On the one hand,

there were the intellectual nationalists, devious, half-educated manipulators,

who were seeking to mobilize the ignorant Muslim masses against

Britain and her Allies; and on the other hand, there were the traditionalist,

‘clerical’ and ‘conservative’ forces whose sincerely held religious concepts

were not incompatible with, nor necessarily hostile to, the romantic Tory

imperialism he himself espoused. These conservative Muslims were precisely the

sort of men who might be trusted to lead the ‘friendly native states’ which he

and Kitchener were advocating; and in the person of the Sharif of Mecca he

believed they had found such a promising figure. As for those scheming

intellectual Muslim nationalists, Sykes believed they were very much like the

leaders of the Turkish CUP. Their objective was to engross all political power

in the hands of a clique of journalists, pleaders, and functionaries, to oust

the clerical element, but to retain its power to excite an ignorant mob to

massacre or rebellion when necessary … An ‘intellectual’ with an imitation

European training, with envy of the European surging in his heart … sees in

Islam a political engine whereby immense masses of men can be moved to riot and

disorder … The Muslim ‘intellectual’ uses the clothes of Europe and has lost

his belief in his creed, but the hatred of Christendom and lust for the

domination of Islam as a supreme political power remains

After leaving India,

Sykes’s first stopover was Basra where he arrived on 19 September 1915. Sykes

was informed that Captain Arnold Wilson, responsible for the Basra vilayet,

would be pleased to meet him. The meeting was not a happy one. By now, the recently

promoted Wilson had returned to full-time political duties and was living in a

cramped office at Ashar, the old Turkish customs post on the banks of the

Shatt al-‘Arab where the Ashar creek meets the Shatt and leads up to

the old city of Basra. Although he was by now quite ill, suffering

intermittently from malaria and a form of beriberi, his appetite for work

remained undiminished. ‘AT’, as he was now commonly known, had recently

acquired a great enthusiasm for paperwork, taking great pride in multiplying

files, assembling card indexes and firing off telegrams at every opportunity.

Sykes found him in full cry, dashing through an enormous pile of waiting for

papers and disposing of them one after another like a threshing machine. Sykes

could be tactless when he was expounding one of his many enthusiasms or

prejudices and on this occasion, he made it abundantly clear to Wilson that in

India he had acquired a dim view of that country’s administration and he took

an equally dim view of the government of India’s predominance in Iraq. There

was no understanding, Sykes insisted, that Iraq was an imperial concern, not

just an Indian one, and therefore the views of London and Cairo must always be

taken into account when deciding military and political policy in this

particular theater. Moreover, Sykes couldn’t understand why so little effort

was being made to win the Iraqi Arabs round to actively supporting Britain.

Surely the Civil Administration could be more active in the propaganda line,

leaflets in Arabic, that sort of thing? And couldn’t they make greater efforts

to win over local sheiks, raise guerrilla bands to attack the Turkish flanks

and so on? In spite of his position of authority in the Civil Administration,

Wilson was still only a relatively junior officer and he must have felt

constrained to suffer this tactless onslaught from his aristocratic and

distinguished official visitor. But he was later to comment with concealed

bitterness that Sykes was ‘too short a time in Mesopotamia to gather more than

fragmentary impressions’, and that ‘he had come with his mind made up and he

set himself to discover the facts in favor of his preconceived

notions, rather than to survey the local situation with an impartial eye.’ In

particular, Sykes seemed overly concerned about doing ‘justice for Arab

ambitions and satisfy France’. Arab ambitions and French satisfaction: the two

concepts seemed hardly compatible; that was precisely what was beginning to

trouble Sykes as he traveled back from India. Over the last few months, he had

begun to appreciate that the French also had ‘desiderata’ in the Middle East.

Indeed, according to intelligence, he was receiving it was clear that they had

expectations of planting the tricolor at the eastern end of the Mediterranean

to accompany their colonies in North Africa. But since Britain’s interests

would be best served by a ‘devolved’ Ottoman Empire of ‘friendly native

states’, these two national objectives were clearly contradictory. Perhaps

there would, after all, have to be some kind of agreement on ‘zones of control’

with France.

On 17 November 1915

Sykes arrived in Cairo, the next leg of his journey home. Here he was shown

some important correspondence between the British high commissioner of

Egypt, Sir Henry McMahon, and the Sharif of Mecca in which the former, on

behalf of the British government, appeared to be offering some kind of

independent Arab state to the latter if the Sharif and his four sons launched a

revolt in the Hejaz against the Turkish government. In spite of continuing

disagreements about the exact boundaries of this new Arab state – and Hussein

was angling for a kingdom of vast proportions – all the signs pointed to an

eventual revolt by the Sharif and his sons.

Thus the die had now

been cast and Britain would have to try to patch up an agreement with the

French which somehow or other satisfied both countries while at the same time

leaving Hussein with something for which he and his Arab movement would still

be willing to fight. There was no question about it: it was going to be very

difficult. Then, out of the blue, the first hint of a solution emerged – if not

a solution at least a step in the right direction. An Iraqi Arab deserter from

the Ottoman army at Gallipoli, a certain Lieutenant Muhammad Sharif

al- Faruqi, was brought in to see him.

The Arab Question And The ‘Shocking Document’ That

Shaped The Middle East

The first meeting of

the British interdepartmental committee headed by Sir Arthur Nicolson with

François Georges-Picot had taken place on 23 November 1915. The French

representative was not convinced of the importance of inducing the Emir of

Mecca and the al-Fatat Arab nationalists to side with the Entente. Austen

Chamberlain reported to Lord Hardinge that Picot had ‘expressed

complete incredulity as to the projected Arab kingdom, said that the Sheikh had

no big Arab chiefs with him, that the Arabs were incapable of combining, and

that the whole scheme was visionary.' The secretary of state for India was very

pleased. It seemed that the French delegate ‘knows his Arab well. I expect he

has sized up the Sheikh’s scheme pretty accurately. I doubt if it has any

element of solidity or that any promise will have weight with the Arabs until

they are absolutely convinced that we are winning.’¹

Moreover, French

demands – which according to Picot the French were obliged to make as ‘no

French government would stand for a day which made any surrender of French

claims in Syria’ – were rather excessive. Picot informed the Nicolson committee

that France claimed the:

Possession

(nominally, a protectorate) of land starting from where the Taurus Mts approach

the sea in Cilicia, following the Taurus Mountains and the mountains further

East, so as to include Diabekr, Mosul and Kerbela, and then returning to

Deir Zor on the Euphrates and from there southwards along the desert

border, finishing eventually at the Egyptian frontier.

Picot, however, added

that he was prepared ‘to propose to the French government to throw Mosul into

the Arab pool if we did so in the case of Bagdad’. In amplification,

Nicolson minuted that Picot had:

Intimated his

readiness to proceed to Paris to explain personally our view – and the Arab desiderata.

M. Cambon told me that he had objected to this visit, on the ground that he

would not be well received at the Quai d’Orsay were he to carry with him such

unpalatable proposals as he had suggested. M. Picot would, therefore,

communicate with Quai d’Orsay in writing. We must, therefore, await the reply.²

The French reply had

not yet been received when a telegram from Sir Henry McMahon arrived on 30

November. In this telegram the high commissioner gave his considered opinion on

Hussein’s letter of 5 November, and at the same time took the opportunity to defend

himself against Chamberlain’s charges. He observed that the Emir’s letter was:

Satisfactory as

showing a desire for mutual understanding on reasonable lines. It also affords

an opportunity of meeting the wishes of the Government of India with regard to

Mesopotamia by some change of formula, but I cannot personally think of any

formula on that subject more favorable to Indian interests than the one

employed in my former letter, without raising Arab suspicions.

With regard to

nonentity of Shereef […] Everything would tend to prove that he is of

sufficient commanding importance, by position descent and personality, to be

the only possible central rallying point for Arab cause, and sufficiently anti-

Turkish to be in great personal danger at Turkish hands.

McMahon did not fail

to point out that his negotiations with Hussein were in a quandary thanks to

the policy ‘of awaiting in Egypt the threatened Turco–German advance’. It

jeopardized ‘any attempt to secure Arab cooperation’, and made it ‘appear

unwise urging Arabs into premature activity which through want of our support

and fear of Turkish retaliation might hasten their abandonment of our cause’.

At the same time it rendered ‘alienation of Arab assistance from Turks a matter

of great importance, and we must make every effort to enlist the sympathy and

assistance, even though passive, of Arab people’. In view of this difficult

situation, McMahon proposed to reply to Hussein along the following lines:

1. Acknowledge

his exclusion of Adana and Mersina from Arab sphere. […]

2. Agree

that with the exception of tract around Marash and Aintab, vilayets

of Beirut Aleppo are inhabited by Arabs but in these vilayets as elsewhere in

Syria our ally France has considerable interests, to safeguard with some special

arrangements will be necessary and as this is a matter for the French

government we cannot say more now than assure the Shereef of our earnest wish

that satisfactory settlement may be arrived at.

3. With

regard to the vilayets of Basra and Baghdad some such arrangement as he

suggests would provide suitable solution, i.e. that these vilayets which have

been taken by us from the Turks by force of arms should remain under British

administration until such time as a satisfactory mutual arrangement can be

made.

4. Assurance

of the Shereef that Great Britain has no intention to conclude peace in terms

of which freedom of Arabs from Turkish domination does not form essential

condition. (On some assurance of this nature sole hope of successful understanding

depends).

5. Appreciation

of Shereef’s desire for caution and disclaim wish to urge him to hasty

action jeopardising Arab projects but in the meantime he must spare

no effort to attach Arab peoples to our cause and prevent them assisting the enemy,

as it is of the success of these efforts and on active measures which the Arabs

may hereafter take in our cause when the time comes that permanency of present

arrangement must depend.

McMahon concluded by

expressing the hope that the Foreign Office would be able to reply ‘without

undue delay’, but, as George Clerk minuted, the Foreign Office could not

answer until they had received ‘the views of the Government of India […] an Alexandretta

expedition has been finally decided, one way or the other, [and] having

prepared a reply […] get the concurrence of the French government’. It was

‘therefore of little use discussing Sir H. McMahon’s views now’.

The India Office

reacted first. Sir Arthur Hirtzel observed that the India Office:

Agree with Sir H.

McMahon that for the success of these negotiations some display of force is

necessary to which the Arabs can rally.

Whether such is

possible, and, if so, where and how, are questions for the British and French

governments and their military advisers.

If it is not

possible, we doubt whether there is any real use in pursuing these

negotiations. But if it is considered expedient for the sake of appearances to

do so, they should be as vague as possible regarding future commitments.

Apart from a few

minor modifications, Hirtzel approved the proposed reply, even the

suggestion to ‘disclaim wish to urge him to hasty action’. The India Office

also qualified Chamberlain’s earlier proviso that McMahon’s promises only held

good if the Arabs acted at once (see Chapter 3, section ‘Four Towns and Two

Vilayets’). This no longer applied in case ‘there is to be no display of force.

But, if there is, Arab assistance must be immediate and universal.’³

A French reply was

not forthcoming. On 10 December, Nicolson decided to wait no longer. If the

Foreign Office kept on waiting:

We shall lose much

valuable time – and it is essential to send a reply to the Shereef as soon as

possible. In regard to Syria, McMahon can say that as the interests of others

are involved he must consider the point carefully. I think a further communication

[…] will be sent later – he can then proceed to reply on all the other points.

Would you draw a telegram embodying I.O.’s views and the viceroy’s wishes – and

we should get I.O. concurrence and Lord Crewe’s the sooner we can get of this

telegram the better.

After it had been

approved by Chamberlain and Crewe, a telegram was sent to Cairo the same day:

Importance of display

of British or Allied force round which Arabs can rally is fully recognized

here, but you will realize that present situation at Gallipoli and Salonica

makes it out of the question for the moment to embark on any other expedition.

Attitude of French

government in regard to Syria is also very difficult and we have little hope of

obtaining from them any assurance that will really satisfy Arabs.

On the other hand, we

must try to keep the negotiations with the Sherif in being, and you

are authorized to reply to him as follows:

- Points 1 and 2, as

you propose.

As regards point 3,

you should say that as the interests of others are involved, the point requires

careful consideration by His Majesty’s Government and a further communication

in regard to it will be sent later.

Point 4. We should

prefer to say that His Majesty’s Government are, as the Sherif knows,

disposed to give a guarantee to assist and protect the proposed Arab Kingdom as

far as may be within their power, but their interests demand, as the Sherif has recognised,

a friendly administration in the Vilayet of Bagdad and the safeguarding of

these interests call for much fuller and more detailed consideration of the

future of Mesopotamia than the present situation and the urgency of the

negotiations permit.

Point 5. The first

[…] assurance you propose. Point 6 […] As you suggest.⁴

In anticipation of

the Foreign Office telegram, McMahon wrote a private letter

to Hardinge on 4 December in which he tried to justify his actions

with regard to the negotiations with Hussein. He claimed that the viceroy took

‘the idea of a future strong united independent Arab State […] too seriously’,

as ‘the conditions of Arabia do not and will not for a very long time to come,

lend themselves to such a thing’. Sir Henry moreover did ‘not for one moment go

to the length of imagining that the present negotiations will go far to shape

the future form of Arabia or to either establish our rights or to bind our

hands in that country. The situation and its elements are much too nebulous for

that.’ His only objective had been ‘to tempt the Arab people into the right

path, detach them from the enemy and bring them on our side’. As far as Britain

was concerned, this was ‘at present largely a matter of words and to succeed we

must use persuasive terms and abstain from academic haggling over conditions –

whether about Baghdad or elsewhere’.⁵

McMahon also sought

the support of the sirdar. Wingate was honored with a letter for the first

time. McMahon excused his negligence in answering Wingate’s letters by

explaining that he was ‘a poor correspondent at the best of times’, and that a

correspondence also was not really necessary as Clayton kept them both fully

informed of each other’s ideas and views. After this apology, he proceeded to

complain about ‘the curious and, to me, mistaken attitude which India is taking

in the matter’, as well as ‘the unreasonable and uncompromising attitude of

France in regard not only to Syria but an indefinitely large hinterland in

which she will not recognize Arab interests’. Indian and French opposition,

combined with Britain’s ‘failure to hold out a hand to the Arabs by putting a

force into Cilicia’, made it likely that Britain would ‘lose all chance of Arab

cooperation and sympathy and drive them into the enemies hands against us’.⁶

McMahon was familiar

with the French position because Alfred Parker had forwarded a report on

Picot’s meeting with the Nicolson committee to Clayton. The latter had

circulated this report, with a covering note, to Maxwell, McMahon and Wingate.

In this note, Clayton observed that the result of the meeting was ‘only what

might have been expected with M. Picot as the representative of the French

government’, considering that Picot was ‘well known as being extreme in his

ideas, and completely saturated with the vision of a great French possession in

the Eastern Mediterranean’. Clayton took the opportunity to emphasize why he

was in favor of negotiations with the Arabs. These were important, not because

they might result in the Arabs actively supporting the Entente in the war

against the Ottoman Empire – which after the dismissal of the Alexandretta

scheme was out of the question anyway – but because they might prevent the

Arabs from joining the Turks and Germans. If the latter happened, then the call

for the jihad would become effective. The great gain resulting from a

successful conclusion of these negotiations was that Britain secured the

passive support of the Arabs:

In considering the

Arab movement, too much attention has been given to its possible offensive

value, and it has to some extent been forgotten that the chief advantage to be

gained is a defensive one, in that we should secure on their part a hostile

attitude towards the Turks, even though it might be only passively hostile, and

rob our enemies of the incalculable moral and material assistance which they

would gain were they to succeed in uniting against the Allies the Arab races

and, through them, Islam.⁷

McMahon incorporated

Clayton’s note into a telegram on the Arab question that was sent to London

three days later. He informed Grey that ‘selection of Picot as their

representative on recent committee on this question is discouraging indication

of French attitude’. The French delegate was ‘a notorious fanatic on Syrian

question and quite incapable of assisting any mutual settlement on reasonable

common sense grounds which present situation requires’. As far as the

negotiations with the Arabs were concerned, ‘conditions of Arabia never

justified expectation of active or organised assistance such as some

people think is object of our proposed mutual understanding. What we want is

material advantage of even passive Arab sympathy and assistance on our side

instead of their active cooperation with enemy.’ Clerk quite agreed with

McMahon’s opinion of Picot.

The latter had ‘been

particularly chosen, for his very fanaticism’. All in all, things could no

longer go on in this fashion:

The question is so

serious that I think it must be treated between government and government, and

no longer between M. Picot and this department. This is a matter for

consideration by the War Committee and I would venture to urge that that body

should hear the views of Sir Mark Sykes, who is not only highly qualified to

speak from the point of view of our interests, but who understands the French

position in Syria today – and in a sense sympathizes with it – better probably

than anyone.

Nicolson and Crewe

concurred in this suggestion. Two days later, Prime Minister Asquith informed

the Foreign Office that ‘Sir M. Sykes might be invited the next meeting of the

War Committee. The India Office shall also be represented.’ ⁸

Enter Sir Mark Sykes

Wingate and Clayton

regarded Lieut.-Colonel Sir Mark Sykes, Bart., MP as their champion in the

London battle for an active, pro-Arab policy. On 9 December, Wingate wrote to

Sir John Maxwell that Sykes, ‘should be a powerful ally in regard to Arab

policy’, while the next day, in a letter to Clayton, he expressed the hope that

‘Mark Sykes’s arrival in London on the 8th will mean that a definite Near

Eastern Policy will be adopted without more hovering’. The Sudan agent for his

part believed that now ‘Lord K. is at home again and also Sykes […] things may

have gone better recently’.⁹

Sir Mark’s

involvement with the Middle East dated from 1890, when he, at eleven years old,

had accompanied his father on a journey through Palestine, Syria and Lebanon.

This was the first of five prolonged travels in which he ranged the Fertile

Crescent. Inspired by his travels, Sykes had written two books – Through Five

Turkish Provinces and Dar-ul-Islam – which had established his reputation as an

expert on the Middle East, even though his knowledge of Arabic was limited

seeing that he could neither read nor write the language. At the end of 1904,

Sykes had been appointed honorary attaché at the Constantinople embassy. He had

occupied this post up to the end of 1906. Most of his stay had been taken up

with another bout of traveling through the Middle East, but he had also

developed intimate relations with Gerald Fitzmaurice, the chief dragoman,

Aubrey Herbert, George Lloyd and Lancelot Oliphant.¹⁰

It had been Oliphant

who had introduced Sykes to Oswald Fitzgerald, early in September 1914. On that

occasion, Sir Mark had offered his services.¹¹ This offer had not been accepted

straight away, and for the time being he had been forced to stay with his

territorial battalion at Newcastle. In a letter to his wife Edith, Sykes had

given voice to his disappointment ‘not to be where I could be most useful,

i.e., in the Mediterranean. Is it not ridiculous the haphazard way we do

things!’ ¹² However, Sykes had finally been ordered to come to London in March

1915, and was ‘appointed at the personal request of Lord Kitchener as a member

of the Committee formed to ascertain British desiderata in Asiatic Turkey’.¹³

Besides Sykes, this

committee consisted of representatives from the Foreign Office, the India

Office, the Admiralty and the Board of Trade. It was chaired by Sir Maurice De

Bunsen, until the outbreak of war, British ambassador at Vienna. During 13

meetings, from 12 April to 28 May 1915, the commission busied itself with

deter- mining British desiderata with respect to the future of the Asiatic part

of the Ottoman Empire. These deliberations resulted in a voluminous report,

which was presented to the Cabinet on 30 June.

In its ‘preliminary

considerations’ the committee stated that ‘our Empire is wide enough already,

and our task is to consolidate the possessions we already have, to make firm

and lasting the position we already hold, and to pass on to those who come after

an inheritance that stands four-square to the world’. Against this background,

the committee opted for a scheme in which, ‘subject to certain necessary

territorial exceptions’ – Basra, Smyrna and the Asiatic part of Constantinople

would have to be ceded, respectively, to Britain, Greece and Russia – the

independence of the Ottoman Empire was maintained, ‘but the form of government

to be modified by decentralisation on federal lines’, while Arab

chiefs would be granted ‘complete administrative autonomy’ under Turkish

sovereignty.¹⁴

Sykes was unable to

append his signature to the report, because he left England at the beginning of

June. The War Office had instructed him to discuss the committee’s findings

with the British authorities in the Near and Middle East, and at the same time

to study the situation on the spot. He successively visited Athens, Gallipoli,

Sofia, Cairo, Aden and again Cairo. Sir Mark subsequently sailed for India.

There he gained but a poor opinion of the capacities of the Indian authorities,

and was angered by their attitude towards the Muslims. It seemed that the only

thing they could think of was not upsetting ‘religious susceptibilities, a

phrase which is beginning to get on my nerves’.¹⁵ Sykes’s visit nevertheless

passed off rather smoothly. His subsequent visit to Mesopotamia was not without

incidents. Nine months later, Lloyd explained to Clayton that Sykes seemed ‘to

have been amazingly tactless, and not only to have rather blustered everyone

but also to have decried openly everything Indian, in a manner which was bound

to cause some resentment’.¹⁶ Arnold T. Wilson, at the time assistant political

officer, Force ‘D’ , observed in his memoirs:

He was too short a

time in Mesopotamia to gather more than fragmentary impressions. He had come

with his mind made up, and he set himself to discover facts in favor of his

preconceived notions, rather than to survey the local situation with an

impartial eye. Whatever we were doing to change the Turkish regime, or to

better the lot of the Armenian, Jew and Sabaean minorities, had his cordial

approval – for the rest, we must do justice to Arab ambitions and satisfy

France!¹⁷

Shortly after the

receipt of Hussein’s third letter, Sykes was back in Cairo. During his third

stay at the Egyptian capital within six months, Sykes dispatched a number of

telegrams to General Callwell. To a large extent these telegrams echoed

Cairo’s point of view with regard to the Arab question: the matter was urgent

and a decision had to be taken as soon as possible; a sympathetic attitude by

the Arabs towards the Entente was of the utmost importance, if only to prevent

the dreaded jihad; a settlement of the conflicting French and Arab claims was

feasible, as was a formula protecting Indian interests in Basra and Baghdad;

and, finally, the Arabs would not act before a landing at Alexandretta had

taken place.

Enter Sherif Al-Faruqi

Faruqi knew very

well that only a tiny proportion of Ottoman army officers belonged to

al-‘Ahd: his figure of 90 per cent was pure fabrication. He also knew that his

claim that al-‘Ahd included a ‘part of the Kurdish officers’ was

misleading, to say the least – there were perhaps no more than a handful of

members who were of Kurdish origin. Faruqi certainly did not unite

the al-Fatat and al- ‘Ahd movements: that was achieved by a senior

Iraqi officer, Yasin al-Hashimi. Al-‘Ahd had never carried out propaganda

among the Arab troops: on the contrary, its members had tried as much as

possible to conceal their activities. There had been no approach to

al-‘Ahd by the Turks or Germans offering an alliance,

as Faruqi in- formed Shuqayr (the Germans had never even

heard of al-‘Ahd). And Faruqi had not been authorized by al-‘Ahd, the

Sharif or any other part of the ‘Arab movement’ to‘receive’ the British

response to their demands.

Furthermore, as

regards the ‘information’ which Sykes obtained from Faruqi during

their interview, there was no ‘Arab Committee’ in Cairo. Neither the

(non-existent) committee nor Faruqi himself was in communication with

Sharif Husayn – in fact, it was to be a further month before Faruqi

contacted Husayn and informed him of his existence. And with respect to French

influence, although Hussein was later to offer some flexibility over French

interests in the coastal region of Syria at Britain’s request, at this point in

time both he and the majority of al-‘Ahd members were strongly opposed to

any French involvement in a new Arab state, in spite of

what Faruqi may have said to Sykes.

So, comforted by the

apparent ‘reasonableness’ of the Arab movement, as relayed to him

by Faruqi, as see underneath, Sykes returned to England where, almost

immediately, he was thrust into negotiations with M. Charles François

Georges-Picot, French counsellor in London and former French consul general in

Beirut, to try to harmonize Anglo-French interests in ‘Turkey-in-Asia’. For

nine months the French had been intermittently raising this question with

Britain. So during the first week of January 1916, Sykes and Picot hammered out

a draft agreement. Finally, as a result of an exchange of letters between Sir

Edward Grey, the French foreign minister, Paul Cambon, and Serge Sazonov,

the Russian minister of foreign affairs, a secret agreement was reached among

the three Great Powers defining their respective claims on Turkey’s Asian

provinces. Its terms were embodied in a letter from Grey to Cambon dated 16 May

1916, and in due course, it was to become known as the ‘Sykes–Picot Agreement’.

On 20 November, after

an interview with Faruqi, Sykes telegraphed to London, that he:

Anticipating French

difficulty, discussed the situation with him with that in view. Following is

best I could get, but seems to me to meet the situation both with regard to

France and Great Britain. Arabs would agree to accept as approximate northern

frontier Alexandretta-Aintab-Birijik- Urfa-Midiat-Zakho-Rowanduz. Arabs would

agree to convention with France granting her monopoly of all concessionary

enterprise in Syria and Palestine, Syria being defined as bounded by Euphrates

as far south as Deir Zor, and from there to Deraa and along Hedjaz Railway

to Maan.

Sykes also informed

the DMO that Faruqi insisted that the whole scheme depended on

‘Entente landing troops at a point between Mersina and Alexandretta,

and making good Amanus Pass or Cilician gates. He further stipulated

that Shereef should not take action until this had been done.’ Sykes added that

he agreed with Faruqi. It was ‘out of the question […] to call on Shereef

or Arabs to take action until we had made above mentioned passes secure’.¹⁸ The

day before, Sykes had sent off another tele- gram in which he had suggested

possible solutions to the territorial aspects of the Arab question. A far as

the vi- layets of Baghdad and Basra were concerned, these were

‘incapable of self-government and a new and weak state could not administer

them owing to Shiah and Sunni dissension. We might agree with Arabs

to administer these provinces on their behalf allocating certain revenues to

their exchequer […] (this corresponding to their demand for subsidy).’ At the

end of this telegram, Sykes had explained that he made his suggestions because

he believed that:

The situation is

critical. I feel that Arab nationalism as such presents no danger for India now

or in future unless we confine ourselves to the canal defensive and let Turk

and German masses assemble in Syria and northern Mesopotamia and reestablish

their prestige and so work a real Jehad with Arab support.¹⁹

Small wonder Wingate

and Clayton looked forward with confidence to Sir Mark’s return to London.

Sykes did not let them down, witness the statement on the Arab question he made

to the War Committee on 16 December. After an exposition in which he stressed that

the Arab nationalists were averse to revolutionary ideologies, tolerant of

other religions and favourably disposed towards Great Britain, he

observed that, with respect to the Arab question:

If I may say so, the

chief difficulty seems to me to be the French difficulty, and the root of that,

I think, to speak frankly, lies in Franco-Levantine finance. Vitali represents

the French group which used to be at Constantinople, who is in touch with M. Hugenin,

who is a Swiss, and he is in touch with the Bagdad railway, and they have a

great many relations with Javid. They have obtained the Syrian railways, and

that very big loan of 1914, which gave them immense concessions all over

Turkey. Now that party, I feel, is working through two agencies, and is

checking the Entente policy in the Near East. One is the French cleric which is

sentiment.

When Asquith interjected

‘What is that?’, Sykes added in clarification that he was referring to the

French nationalist party:

Which is sentimental,

bearing in mind the crusades. I think that that financial group works upon a

perfectly honest sentiment. On the other side, they work on the fears of the

French colonial party of an Arab Khalifate, which will have a common language with

the Arabs in Tunis, Algeria, and Morocco […] I think at the back of all this,

the influence that is moving them, is sinister.

Sykes considered the

French financiers ‘a very evil force working two honest forces, which are

unconscious of the real purport of it’. He proposed that Britain should pursue

a policy consisting of three steps. First:

We ought to settle

with France as soon as possible, and get a definite understanding about Syria.

Secondly, to organise a powerful army in Egypt which is capable of

taking the offensive; and, thirdly, to coordinate our Eastern operations. Get that

as one machine, and one definite problem: link up Aden, Mesopotamia – the whole

of that as one definite problem for the duration of the war. If we had that I

think it is worth backing the Arabs, no matter what ground we may have lost to

the north of Haifa.

Asked by Asquith how

he would come to terms with the French, Sykes stated that: I think

that we have those two assets. I think we can play on the French colonial if we

work it well: get into the French colonial’s head what a Committee of Union and

Progress Sherif means, and point out what they have done in India and

what they might do elsewhere. I think the French clerical is quite capable of

being influenced by reason of the danger to his one asset in Syria, and if you

rob the occult French financial force of its two agencies, then, I think you

are on the high road to a settlement.

In answer to a

question by Lloyd George, Sykes repeated his opinion that the Arab question

should first have to be settled with France before any military action could be

contemplated. With respect to that, he observed that Egyptian military opinion

‘strongly [held] the idea of making a landing at Alexandretta’, which was

confirmed by Kitchener.²⁰

In the course of the

subsequent discussion, Asquith wondered what military value attached to the

Arabs. Echoing Clayton, Sykes replied that their value was mainly negative. The

Arabs were ‘bad if they are against us, because they add to the enemy’s forces,

and if they are on our side there is so much less for the enemy and a little

more for us, but I do not like to count upon them as a positive force to us’.

To Balfour the situation was clear: ‘If we decide to do nothing, first of all

we shall lose the Sherif, and after him we shall lose the Arabs, and lose

them forever’. However, Lloyd George and Crewe – again deputising for

Grey – first wanted to know whether or not a landing at Alexandretta was

feasible, because, as Crewe argued: ‘it is no good starting on any proposals

with France until we have made up our mind that a big military effort is

possible’.

Before Sykes

withdrew, he was given the opportunity to emphasize once again that:

The question is very

urgent: it is important that a decision should be given quickly. Every day that

we delay we lose more and more Arabs from our side, and every day that we put

off brings us nearer to the day when there will be many Turks in Syria.

After he had left,

the members of the War Committee further discussed the Arab question. Kitchener

once again repeated that ‘the offensive-defensive’ – as Balfour put it – was

indeed the best way to defend Egypt. Balfour proposed that the French send troops,

although not to Alexandretta, but to Ayas Bay. Kitchener concurred,

as ‘the Turks expect us at Alexandretta, which has been entrenched, but there

are no entrenchments at Ayas’. Asquith believed that this was ‘an

attractive programme’. At the suggestion of Crewe, it was decided first to

consult Bertie before approaching the French government.²¹

Crewe dispatched a

letter to Bertie the next day. He acquainted the ambassador with the views,

Sykes had expressed before the War Committee. As far as the ‘offensive

defensive’ was concerned, Crewe fully realized that ‘then we come up against

French susceptibilities and claims, and any discussion becomes exceedingly

delicate, because the French always seem to talk as though Syria and even

Palestine were as completely theirs as Normandy’. The War Committee therefore,

believed that ‘it might be advisable for Mark Sykes to go over to Paris,

accompanied, perhaps, by someone like Fitzmaurice, in order to talk to some of

the French Ministers. He could press his own views upon them without committing

us to any particular movement.’ Bertie, however, opposed ‘the Sykes expedition

to Paris’. He argued that:

However intelligent

Sir Mark Sykes may be, and however good his arguments, I do not think that his

coming to Paris to talk to some of the French Ministers would be in the least

useful. However much he might press his views as his own views, they would be

regarded as the views of the British government; for otherwise, why should he

come?

The ambassador was

prepared to sound Briand personally on ‘a possible joint expedition somewhat

north of Egypt’, but warned that ‘contrary to Kitchener’s persistent

contention, they hold that Salonica and the possibility of an expedition

somewhere not defined will prevent the Germans starting any considerable

Turkish or Turco– German force for a march to Egypt’.²²

On 28 December 1915,

the War Committee indirectly decided to shelve the whole project. It accepted

the recommendations on military policy for 1916 made by Lieut.-General Sir

William Robertson, Murray’s successor as CIGS.²³ These were based on the

decision taken at an inter-allied conference at Chantilly on 8 December that

the war could only be won on the Russian, French and Italian fronts, and that

the number of troops on the other fronts should be reduced to the barest

minimum. Consequently, an ‘offensive-defensive’ policy for

the defence of Egypt was out of the question, at least for 1916. In

his memoirs, Hankey observed that:

Robertson must have

come away from the meeting of December 28th well satisfied. He had obtained the

adoption of his main principle that the western front was the main theatre of

war and he had been authorized to prepare for a great offensive there.

He had also secured the application of the principle of a defensive role to the

Egyptian and Mesopotamian campaigns.²⁴

Sir Mark Sykes And François Georges- Picot Come To An

Agreement

The second meeting

between the Nicolson Committee and Georges-Picot took place on 21 December

1915. Picot informed the British delegation that ‘after great difficulties, he

had obtained permission from his government to agree to the towns of Aleppo,

Hama, Homs, and Damascus being included in the Arab dominions to be

administered by the Arabs’.²⁵ The discussion then turned to the boundaries of

the area that should come under direct French administration, as well as the

question of which part of the future Arab state would fall within the French

sphere of influence. With respect to the latter, it was agreed that the Arab

state should be ‘divided between England and France into spheres of commercial

and administrative interest, the actual line of demarcation to be reserved, but

[…] that it should pivot on Deir el Zor eastward and westward’.

It was also decided that the Lebanon, which ‘should comprise Beirut and the

anti- Lebanon’, and an enclave around Jerusalem should be excluded from the Arab

territories.

Two points were

reserved for further discussion: ‘the allocation of the Mosul Vilayet [and] the

position of Haifa and Acre as an outlet for Great Britain on Mediterranean for

Mesopotamia’.²⁶ This fresh delay made Nicolson complain to Hardinge that

‘our discussions with the French in regard to the Arab negotiations are

proceeding exceedingly slowly, and I cannot say that I see much prospect of our

coming to an agreement’.²⁷ Sykes on the other hand, was rather sanguine. On 28

December, he in- formed Clayton that he had ‘been given the Picot negotiations.

I have prepared to concede Mosul and the land north of the lesser Zab if Haifa

and Acre are conceded to us.’ Sykes expected that it would not take him ‘above

3 weeks’ to solve the last problems with the ‘Picot negotiations’.²⁸

Sykes’s optimism

turned out to be justified. Within a week he came to an understanding with

Georges-Picot. The terms of the proposed agreement were laid down in a

memorandum that reached the Foreign Office on 5 January. Sykes and Picot

claimed that three parties were involved in a settlement of the Arab question –

France, the Arabs and Great Britain – and that each cherished territorial,

economic and political ambitions that could not be satisfied without coming

into conflict with those of the difficulties, he had obtained permission from

his government to agree to the towns of Aleppo, Hama, Homs, and Damascus being

included in the Arab dominions to be administered by the Arabs’.²⁵ The

discussion then turned to the boundaries of the area that should come under

direct French administration, as well as the question of which part of the

future Arab state would fall within the French sphere of influence. With

respect to the latter, it was agreed that the Arab state should be ‘divided be-

tween England and France into spheres of commercial and administrative

interest, the actual line of demarcation to be reserved, but […] that it should

pivot on Deir el Zor eastward and westward’. It was also decided

that the Lebanon, which ‘should comprise Beirut and the anti- Lebanon’, and an

enclave around Jerusalem should be excluded from the Arab territories.

Two points were

reserved for further discussion: ‘the allocation of the Mosul Vilayet [and] the

position of Haifa and Acre as an outlet for Great Britain on Mediterranean for

Mesopotamia’.²⁶ This fresh delay made Nicolson complain to Hardinge that

‘our discussions with the French in regard to the Arab negotiations are

proceeding exceedingly slowly, and I cannot say that I see much prospect of our

coming to an agreement’.²⁷ Sykes, on the other hand, was rather sanguine. On 28

December, he in- formed Clayton that he had ‘been given the Picot negotiations.

I have prepared to concede Mosul and the land north of the lesser Zab if Haifa

and Acre are conceded to us.’ Sykes expected that it would not take him ‘above

3 weeks’ to solve the last problems with the ‘Picot negotiations’.²⁸

Sykes’s optimism

turned out to be justified. Within a week he came to an understanding with

Georges-Picot. The terms of the proposed agreement were laid down in a

memorandum that reached the Foreign Office on 5 January. Sykes and Picot

claimed that three parties were involved in a settlement of the Arab question –

France, the Arabs and Great Britain – and that each cherished territorial,

economic and political ambitions that could not be satisfied without coming

into conflict with those of the other two. From this it followed that ‘to

arrive at a satisfactory settlement, the three principal parties must ob-

serve a spirit of compromise’. This settlement would, moreover, have ‘to be

worked in with an arrangement satisfactory to the conscientious desires of

Christianity, Judaism, and Mahommedanism regarding the status of

Jerusalem and the neighboring shrines’. In the light of these

considerations, they had arrived at the following proposal (see Sykes-Picot map

of 1916):

1. Arabs. – That

France and Great Britain should be prepared to recognize and protect

a confederation of Arab States in the areas (a) and (b) under the suzerainty of

an Arabian chief. That in area (a) France, and in area (b) Great Britain,

should have priority of right of enterprise and local loans. That in area (a)

France, and in area (b) Great Britain, should alone supply advisers or foreign

functionaries at the request of the Arab confederation.

2. Great Britain,

should be allowed to establish such direct or indirect administration or

control as they desire.

3. That in the brown

area [which covered the greater part of Palestine; R.H.L] there should be

established an international administration, the form of which is to be decided

upon after consultation with Russia, and subsequently in consultation with Russia,

Italy, and the representatives of Islam.

4. That Great Britain

be accorded (1) the ports of Haifa and Acre, (2) guarantee of a given supply of

water from area (a) for irrigation in area (b). (3) That an agreement be made

between France and Great Britain regarding the commercial status of Alexandretta,

and the construction of a railway connecting Bagdad with Alexandretta.

5. That Great Britain

have the right to build, administer, and be sole owner of a railway connecting

Haifa or Acre with area (b), and that Great Britain should have a perpetual

right to transport troops 2. That in the blue area France, and in the

red area along such a line at all times.

On the same day, Nicolson

circulated copies of the memorandum to Holderness, Brigadier-General

George Macdonogh, director of military intelligence (DMI), and Captain

Hall, director of the intelligence division (DID) at the Admiralty. In his

covering letter he stated that, although ‘of course the agreement merely

represents the personal views of Sir Mark Sykes and M. Picot’, he believed that

it presented ‘a fair solution of the problem’.²⁹ Only the India Office agreed

with Nicolson’s conclusion. The loss of Mosul would clearly be ‘a serious

sacrifice for us’, but, on the other hand, it would force the French ‘to be

very accommodating elsewhere, e.g. Haifa’. The India Office should like to see

some modifications in the proposed terms, but on the whole the memorandum, as Hirtzel noted,

‘represents a considerable abatement on M. Picot’s original claim, and we are

under a great obligation to Sir Mark Sykes’.³⁰ Macdonogh and Hall

were considerably more critical. They accepted that an early settlement of the

Arab question was important to prevent a jihad, but questioned the assumption

that an agreement with France had to be reached first, before the Arabs could

be dealt with. Macdonogh argued that:

To me it appears that

the one point of importance is to get the Arabs in on our side as early as

possible. I would therefore, suggest that all that is necessary at the moment

is that we should be in a position to inform the Sheikh what are the approximate

limits of the country which we and the French propose to let him rule over.

This may involve an agreement as to the respective British and French spheres

of influence in that district, but I hope that its discussion will not be

allowed to delay the settlement of the main question.³¹

Hall, for his part,

doubted whether it was ‘necessary to have some agreement with the French about

Syria and Mesopotamia, in order that such action may be taken as may avert a

combination between the Turco–German forces and the Arabs, the result of which

would produce something like a serious general Moslem jehad against us’.

According to the DID, ‘action, which will convince the Arabs of our effective

power, is very necessary’. In- deed, ‘force is the best Arab propaganda’, and

it was therefore very desirable that a concerted naval or military action be

undertaken that would ‘result in cutting off the Arabs from the Turks by an

occupying force and so screening the former’, but precisely ‘no such action on

the part of the French, or on our part with their good-will and furtherance is

a term of the agreement’. The proposed agreement was moreover unsatisfactory

considering the assurances Hussein had asked for:

(a) That

the Arabs shall not be deserted by the Allies in any peace which may be made;

and

(b) That

all territories properly considered as inhabited by Arabs shall (with certain

exceptions) be part of an independent Arab State, guaranteed by the Allies. He

does not appear ever to have been willing to exclude Syria, and more especially

the Arab center of Beirut, from the Arab State.

Further, he and other

Arab leaders in touch with the British have, on several occasions expressed

themselves very emphatically against their being placed under any obligation to

accept French advisers locally, whereas they stated that they were prepared to

welcome British.

These considerations

led Hall to the conclusion that ‘the only advantage’ of the proposed agreement

that ‘would at present be gained seems to me the possibility of giving

definiteness to the assurances which would in them- selves be

unsatisfactory’.³² Finally, both Macdonogh and Hall could not help

thinking that, as the former put it, ‘we are rather in the position of the

hunters who divided up the skin of the bear before they had killed it’.³³

Pending Picot’s return from Paris, the observations by Hirtzel, Macdonogh and

Hall drew no comments from Grey or his officials.

On 16 January 1916,

Sykes informed the Foreign Office that he had spoken to Picot, and that the

latter had informed him that ‘at Paris he had much difficulty, but that he

believed that it would be possible to come to an agreement on the lines of the

memorandum’.³⁴ Nicolson convened a further meeting of the interdepartmental

committee on 21 January. During that meeting, ‘the criticisms of the various

Departments on the Sykes-Picot Memorandum were considered and no insurmountable

difficulty to the scheme was put forward in any of them’. Nicolson impressed

upon the other delegates that it was ‘essential to take France in our

confidence before we embarked on final negotiations with the Arabs’, and it was

again laid down that ‘if the Arab scheme fails the whole scheme will also fail

and the French and British governments would then be free to make any new

claims’. Sykes was authorized to inform Picot of the results of the meeting, as

well as that ‘H.M.G. would feel compelled to consult the Russian government after

agreement with the French’ on the northern frontier of the blue area.

As a result of this

meeting, the Foreign Office drew up a draft agreement. Its conditional

character was emphasized by adding a preamble stating that ‘should the

negotiations with the Grand Shereef of Mecca fail to secure the active

cooperation of the Arabs on the side of the Allies the whole proposals in

regard to all spheres whether of administration or of influence will lapse

automatically’. The India Office and the DMI concurred with the draft

agreement. Holderness commented that it was ‘in accordance with the conclusions

reached by the Committee on Friday’, while Macdonogh ‘quite agree[d]

with its contents’. Hall, however, protested anew against the absence of a

‘stipulation for French cooperation in, or consent to, any concerted plan of

action against the Germans and Turks as a condition of the agreement’.³⁵

The Foreign Office

completed the final draft on 2 February. It was circulated to the Cabinet that

same evening, with a covering letter in which Nicolson explained the reasons

for negotiating this agreement with France. It had been ‘found at the outset impossible

to discuss the northern limits of the future Arab State or Arab Confederation,

unless the French desiderata in Syria were also examined, as M. Picot was

unable to separate the two questions’. Eventually, it had been agreed that ‘the

four towns of Homs, Hama, Aleppo and Damascus will be included in the Arab

State or Confederation, though in the area where the French will have priority

of enterprise, etc’. Nicolson did not fail to point out that the preamble

was intended to lay down ‘with sufficient precision’ that ‘the proposals in

regard to the Blue area, as well as the Red area are contingent on the

fulfilment of certain essential conditions’, and that Russia should be given

full opportunity to have a say in the final settlement of the question.³⁶

The War Committee

considered the matter the following day. It was decided on the suggestion of

Sir Ed- ward that ‘the whole Arab Question should be discussed at a meeting

between Mr Bonar Law [the secretary of state for the

colonies], Mr Chamberlain, and Lord Kitchener, and that the French

should be informed if we agreed to their proposals’.³⁷ This meeting took place

the next day. Crewe and Nicolson were present, as well as Holderness

and Hirtzel; ‘a representative of the Admiralty was also present, but was

not in a position to give an opinion on the merits of the scheme’. Those who

were decided that:

M. Picot may inform

his government that the acceptance of the whole project would entail the

abdication of considerable British interests, but provided that the cooperation

of the Arabs is secured, and that the Arabs fulfil the conditions and obtain

the towns of Homs, Hama, Damascus and Aleppo, the British government would not

object to the arrangement. But, as the Blue Area extends so far eastwards, and

affects Russian interests, it would be absolutely essential that, before

anything was concluded, the consent of Russia was obtained.

On the evening of 4

February, Sir Arthur informed Georges-Picot of the British decision.

He minuted afterwards that he had laid ‘emphatic stress on the

absolute necessity of nothing whatever being considered settled until the

Russian consent had been obtained – and […] that we should say nothing to the

Arabs until that consent has been obtained’.³⁸ Five days later, Cambon told

Nicolson that ‘the French government are in accord with the proposals

concerning the Arab question’.³⁹ Sykes and Picot were entrusted with the task

to inform the Russian authorities of the contents of the agreement.

The Arab Question Becomes A Regular Quicksand

Foreign Office

officials had little time to savor the successful conclusion of the

negotiations with the French on the Arab question. On 5 February, Oliphant and

Nicolson occupied themselves with Hussein’s reply to McMahon’s letter of 14

December 1915 (see section ‘Georges-Picot’s Opening Bid and McMahon’s Third

Letter’, above). This letter, dated 1 January 1916, had been received by the

Foreign Office on 2 February. The high commissioner had declared in a telegram

of 26 January that the letter was ‘of friendly and satisfactory nature’,⁴⁰ but

after they had studied it both Oliphant and Nicolson disagreed. The

former minuted that he could not ‘regard

the Sharif’s letter as very satisfactory, though it is at least

outspoken and frank’, while the latter observed that he did not:

Consider this letter

at all satisfactory as regards the Sharif’s remarks respecting the

French and I wish in his telegram […] Sir H. McMahon had given us some

indication of this – He made no mention of the northern parts in his telegram –

and we have had to believe that the Shereef had not taken serious notice of

them while on the contrary he employs rather ominous language in regard to

them.

About the Emir’s

position on these ‘northern parts,' McMahon explained in his covering dispatch

that:

Satisfactory as it

may be to note his general acceptance for the time being of the proposed

relations of France with Arabia, his reference to the future of those relations

adumbrates a source of trouble which it will be wise not to ignore.

I have on more than

one occasion brought to the notice of His Majesty’s Government the deep

antipathy with which the Arabs regard the prospect of French Administration of

any portion of Arab territory. In this lies considerable danger to our future

relations with France, because difficult and even impossible though it may be

to convince France of her mistake, if we do not endeavour to do so by

warning her of the real state of Arab feeling, we may hereafter be accused of

instigating or encouraging the opposition to the French, which the Arabs now

threaten and will assuredly give.⁴¹

McMahon’s

observations reflected Clayton’s anxieties, which the latter had voiced in two

letters to Wingate. The Sudan agent considered ‘the Sharif’s answer

[…] on the whole satisfactory’, but taken together with the results of the

second meeting with Picot on 21 December, he feared that the British could not

go on ‘negotiating much longer, without laying ourselves open to a charge of

breach of faith, unless we honestly tell the Arabs that we have made Syria over

to the French’. A problem that was the more important since:

Some of our Syrian

friends seem to have an inkling that we have handed Syria over to the French

and I foresee some trouble. The time has nearly arrived when we shall have to

tell them so straight out and hand them over to the French to settle with –

other- wise we shall risk giving rise to the very friction with France that we

have sacrificed so much to avoid.⁴²

Wingate was more

optimistic. According to him the results of the meeting were: On the whole not

quite so unsatisfactory as I had expected, and I think I see in the general

trend of the discussion, the possibility of coming to an arrangement which may

satisfy all parties – indeed I do not see that even if French demands are

conceded in their entirety, that we can be accused of any serious breach of

faith – it is true the Arabs will not get all they wanted, but they will

achieve a great deal and in any circumstances, I should think that further

discussions will result in a certain modification of the French demand.⁴³

However, Clayton, in

a further letter, confessed that he did not ‘share these hopes’. He enclosed

copies of McMahon’s covering dispatch with Hussein’s fourth letter, and the

reply the latter intended to send ‘without waiting for formal approval’.

Clayton explained that it had not been an easy assignment ‘having only a couple

of hours to do it in, and [having] to steer clear of the various quick

sands and yet to say something which would satisfy the Sharif’.⁴⁴

Clayton could have spared himself the trouble as far as Grey was concerned. To

him, the Arab question already was ‘a regular quicksand’.⁴⁵

Cambon was rather

more sanguine. In view of McMahon’s suggestion to warn the French ‘of the real

state of Arab feeling’, the India Office had expressed the desire that the

Foreign Office should do so. Of course, it was ‘not unlikely that they will not

take the statement seriously. But Chamberlain apprehends that His

Majesty’s Government may hereafter be under some suspicion of bad faith if,

with the information before them, they allow the negotiations to proceed

without warning the other party.’ Grey had consequently instructed the

department to mention the matter to Cambon.⁴⁶ As the India Office had

predicted, the latter did not take the matter very seriously. He cheerfully

remarked to Nicolson that ‘the Shereef would not be an Arab if he did not say

something of that kind’.⁴⁷

Sykes, meanwhile,

acted as advisor to the British ambassador at Petrograd, Sir George Buchanan,

during the latter’s negotiations on the frontiers of the blue area with the

Russian minister for foreign affairs, Sazonov, and the French ambassador, Paléologue,

who was assisted by Georges-Picot. Grey had observed in his instructions that

Britain had ‘no desire whatever to urge the Russian government to make

concessions in the districts which are of direct interest to them if they have

any objections to doing so’.⁴⁸ Sazonov indeed objected. At the first

meeting of the three parties he showed ‘very plainly he did not like extension

of the blue area so far eastward’.⁴⁹ However, a compromise was reached within

two days, to the effect that the most eastern part of the blue area would

become part of the area under direct Russian administration, while France would

be compensated for the loss of this region ‘by enlarging her blue area to the

north of Marash’.⁵⁰

On 17 March, Buchanan

telegraphed that the Russian government had decided to accept the compromise.⁵¹

At a meeting of the War Committee six days later, it appeared that Balfour,

Kitchener, and Asquith objected to the proposed scheme, albeit on different

grounds. Each time, Grey tried to neutralize their objections

by emphasizing that ‘the whole arrangement was provisional on the

Arabs coming in. Unless they did, there would be no break up of Asia Minor,’

and that, accordingly, ‘he thought that nothing would come of all this, [and]

Asia Minor would never be divided’.⁵² Eventually, it was decided that ‘His Majesty’s

Government would raise no objections to the proposed arrangement between France

and Russia’.⁵³

Despite this

progress, negotiations again could not be brought to a conclusion. Fresh

problems arose with respect to ‘all concessions for railway construction and

other advantages such as religious missions granted to the French by the Turks

in any territory that Russia may acquire’.⁵⁴ The result was that, on 3 April

1916, 171 days after Maxwell had telegraphed that ‘time is of the greatest

importance, and that unless we make definite and agreeable proposal to the

Shereef at once, we may have a united Islam against us’, and 110 days after

Sykes had testified before the War Committee that ‘the question is very urgent:

it is important that a decision should be given quickly. Every day that we

delay we lose more and more Arabs from our side,’ Buchanan still had to impress

on Sazonov the importance of a speedy conclusion of the negotiations

in order that Britain would be ‘able to clinch matters with Arabs at once’.⁵⁵

Sir Mark had

indicated some weeks before that two potential dangers threatened the Arab

revolt:

‘1. Peninsula nomads

moving before intellectual Syrians are prepared and scheme failing through want

of organisation.

2. Of

intellectual Syrians failing to combine with intellectual Mosul

and Irak Arabs to join in movement owing to doubt as to our designs

on Irak’. Concerning the latter, Sykes had suggested sending ‘Arab and

Kurd officers now Turkish prisoners of war in India to Egypt and letting

Colonel Clayton sound those committed to the Arab cause and select best to work

with Masri and Faruki’. Although Oliphant

had minuted that he could not ‘conceal my skepticism as to

the success of the scheme’, Sykes’s telegram had been repeated to Cairo. The

next day, yet an- other telegram had been sent to McMahon, in which he had been

informed that ‘no action whatever should be taken on it’ (i.e. Sykes’s

telegram), but that the Foreign Office would ‘be glad of your observations on

it’.⁵⁶ McMahon considered it wiser to send Aziz Ali and Faruqi to

Mesopotamia and there to get in touch with ‘the Arab element in the Turkish

Army’. There was, however, the problem that they:

Demand for themselves

and Arab military element whom they would have to approach some definite

assurance of British policy towards Arabia. They consider this essential to the

success of any effort to win over Arab element in the Army.

They would be

tolerably content with the assurances already given to the Shereef. Their

tendency at present is to demand less from us with regard to Mesopotamia than

would have been acceptable before.

Oliphant supported

McMahon’s ‘suggestion that these two men should go’. Grey and Kitchener, too,

were in favor of the proposal. Together they drafted – ‘at the

Cabinet this morning’ – a telegram in which the high commissioner

was authorized, provided Clayton did not object, to

send Faruqi and Aziz Ali to Mesopotamia. They also permitted Sir

Henry ‘to give assurances, if necessary, but you should be very careful not to

exceed in any way the limits of the assurances already given to the Shereef’.⁵⁷

Copies of both

telegrams were forwarded to the India Office. Chamberlain was not amused. The

India Office drew the Foreign Office’s attention to Husayn’s letter

of July 1915, in which the Emir:

Purported to speak

for the ‘Arab Kingdom of the Shereef’, while in that of 1st January he

expressly stated that his procedure was not personal, but the result of the

decisions and desires of his peoples of which he was only the transmitter and

executant. There is no clear evidence as to how far this claim accords with

facts, but it has not, so far as Chamberlain is aware, been

questioned by His Majesty’s Government. If the claim is well founded, it is a

point for consideration whether independent assurances should be given to

others, and ex hypothesize less responsible Arabs.

Oliphant minuted that

the telegram to Sir Henry ‘was not a departmental draft,' and proceeded to

draft a telegram in the sense of the India Office letter. Nicolson was

embarrassed by the letter, although he ‘understood that Sir E. Grey and Lord

Kitchener consulted M. Chamberlain before the telegram was dispatched’. He

admitted that there was a good deal of force in the concluding remarks of the

I.O. letter’, but the text of Oliphant’s draft ‘rather clashes with the

telegram sent in 54229 [the one drawn up by Grey and Kitchener] – and would

possibly confuse Sir H. McMahon’.⁵⁸

Two days later, the

Foreign Office received another letter from the India Office, enclosing a

telegram from General Sir Percy Lake, GOC-in-C, Force ‘D’. The latter was

opposed to McMahon’s suggestion. It was:

Not considered

possible that either of the above individuals could themselves pass over from

occupied territory to the sphere of the Turkish troops op- posed to us on the

Tigris or Euphrates, or could be of any practical use to us if they did. From

the political standpoint it appears to us that their political views and

schemes are much too advanced to be safe pabula for the communities

of occupied territories and their presence in any of the towns

of Iraq would be in our opinion undesirable and inconvenient.⁵⁹

Lake’s telegram had

been repeated to Cairo and McMahon promptly reacted. He explained that ‘it was

not intended that Al Masri and others should pass over to Turkish

lines’. All that had been envisaged was that ‘presence of one or two prominent and

carefully selected members of the Arab party in our ranks would afford Arab

elements in Turkish army much required guarantee of our unity of interest and

good faith’. He moreover warned that the decision not to send Aziz Ali

and Faruqi would:

Produce

disappointment and rumors of danger being ascribed either to our

mistrust in their loyalty, or to our unwillingness, if not inability, to carry

out our assurances, and this may not be without effect on Shereef. An

impression is gained that there is a visible limit to the patience of those in

whom we have raised feelings of expectation nor is it possible to guarantee

that the present favorable attitude of certain individuals can be

counted on later.

McMahon, therefore,

trusted that he might ‘continue to give all guarantees short of definite action

and within the limits approved by you to those who have now committed their

destinies to us.'

This telegram induced

Chamberlain to compose a very biting memorandum:

I do not find this

telegram very easy to understand.

The decision to which

it refers is that El Faruki and El-Masri should proceed to

Mesopotamia. As it now appears that Sir H. McMahon never contemplated that they

should pass over to the Turkish lines (as was supposed here), it is not clear of

what use he thought they could be. It is not believed that either of them have

any influence in Irak. How is ‘practical use’ to be made of them?

‘An impression is

gained’, Sir Henry telegraphs, ‘that there is visible limit to the patience of

those in whom we have raised feelings of expectation’. This is the severest

criticism I have seen of Sir H. McMahon’s policy. He raised the expectations.

We have given assurances by his mouth much wider than we at home intended: We

have given money and arms and promised more. The Sharif has done

nothing, and we are now to be told by Sir H. McMahon that it is we who fail to

fulfil the expectations we have raised! Will Sir Henry

ever realize that there are two sides to a bargain that the Shereef

has his part to play and that it is now ‘up to’ him the Shereef to make the

next move?

What does he mean by

‘continuing to give all guarantees short of definitive action?’ He has given

guarantees as already stated in excess of our intentions. He safeguarded French

freedom of action in Syria but not ours in Mesopotamia. But by his declarations

we hold ourselves bound and there has been no suggestion that we should recede

from them. If he only desires to repeat himself, he has authority to do so, but

does he mean that he is to give further assurances, and if so what? I am very

uneasy about the whole handling of the question by Egypt.

Grey’s reaction to

Chamberlain’s complaint was very characteristic. He did not enter into a

discussion on the merits of the latter’s arguments. He confined himself to a

brief note to Nicolson:

You will see

what Mr Chamberlain says. I am disposed simply to telegraph to Sir H.

McMahon that I do not understand his difficulty about assurances that he can

repeat assurances already given but must not go beyond them, that we are I

believe giving arms and money and the sole question is whether and when the

Arabs will do their part.

A telegram in this

sense was dispatched to Cairo on 5 April 1916.⁶⁰

Sykes, the man whose

suggestion had started this controversy, had in the meantime returned to

London.

There he set himself

to solving the problem that according to McMahon constituted the biggest threat

to a satisfactory solution to the Arab question, ‘the deep antipathy with which

the Arabs regard the prospect of French administration of any portion of Arab

territory’. In a telegram sent from Petrograd on 16 March, Sykes had already

declared that ‘with regard to Arabs our greatest danger lies in their falling

out with the French’, but that ‘if I can get Picot and Faroki or Aziz

Ali into a room together, I believe I can manage to patch up a bargain between

them’. He had therefore advised:

Get

El Masri or Faruki or both to London where I could enter

into formal discussion with them and when ground was prepared bring them into

contact with Picot. I suggest this as I fear French and Arab discussions in