By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Modi The Alleged Teacher Of The World

Modi and the BJP seem

poised to win their third general election in a row. This victory would further

magnify the prime minister’s aura, enhancing his image as India’s redeemer. His

supporters will boast that their man is assuredly taking his country toward

becoming the Vishwa Guru, the teacher to the world.

This spring, India is

scheduled to hold its 18th general election. Surveys suggest that the

incumbent, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is very likely to win a third term in

office. That triumph will further underline Modi’s singular stature. He

bestrides the country like a colossus, and he promises Indians that they, too,

are rising in the world. And yet the very nature of

Modi’s authority, the aggressive control sought by the prime minister and

his party over a staggeringly diverse and complicated country, threatens to

scupper India’s great-power ambitions.

A leader of enormous

charisma from a modest background, Modi dominates the Indian political landscape as only two of his 15

predecessors have done: Jawaharlal Nehru, prime minister from Indian

independence in 1947 until 1964, and Nehru’s daughter, Indira Gandhi, prime

minister from 1966 to 1977 and then again from 1980 to 1984. In their pomp,

both enjoyed wide popularity throughout India cutting across barriers

of class, gender, religion, and region, although—as so often with leaders who

stay on too long—their last years in office were marked by political

misjudgments that eroded their standing.

Nehru and Indira

Gandhi both belonged to the Indian National

Congress, the party that led the country’s struggle for freedom from

British colonial rule and stayed in power for three decades following

independence. Modi on the other hand, is a member of the Bharatiya Janata Party, which spent many years in

opposition before becoming what it now appears to be, the natural party of

governance. A major ideological difference between the Congress and the BJP is

in their attitudes toward the relationship between faith and state.

Particularly under Nehru, Congress was committed to religious pluralism, in

keeping with the Indian constitutional obligation to assure citizens “liberty

of thought, expression, belief, faith, and worship.” The BJP, on the other

hand, wishes to make India a majoritarian state in which politics, public policy,

and even everyday life are cast in a Hindu idiom.

Modi is not the first

BJP prime minister of India—that distinction

belongs to Atal Bihari Vajpayee, who was in office in 1996 and from 1998 to

2004. But Modi can exercise a kind of power that was never available to

Vajpayee, whose coalition government of more than a dozen parties forced him to

accommodate diverse views and interests. By contrast, the BJP has enjoyed a

parliamentary majority on its own for the last decade, and Modi is far more

assertive than the understated Vajpayee ever was. Vajpayee delegated power to

his cabinet ministers, consulted opposition leaders, and welcomed debate in

Parliament. Modi, on the other hand, has centralized power in his office to an

astonishing degree, undermined the independence of public institutions such as

the judiciary and the media, built a cult of personality around himself, and

pursued his party’s ideological goals with ruthless efficiency.

Despite his

dismantling of democratic institutions, Modi remains extremely popular. He is

both incredibly hardworking and politically astute, able to read the pulse of

the electorate and adapt his rhetoric and tactics accordingly. Left-wing

intellectuals dismiss him as a mere demagogue. They are grievously mistaken. In

terms of commitment and intelligence, he is far superior to his populist

counterparts such as former U.S. President Donald Trump, former

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, and former British Prime Minister Boris

Johnson. Although his economic record is mixed, he has still won the trust of

many poor people by supplying food and cooking gas at highly subsidized rates

via schemes branded as Modi’s gifts to them. He has taken quickly to digital

technologies, which have enabled the direct provision of welfare and the

reduction of intermediary corruption. He has also presided over substantial

progress in infrastructure development, with spanking new highways and airports

seen as evidence of a rising India on the march under Modi’s leadership.

Modi’s many

supporters view his tenure as prime minister as nothing short of epochal. They

claim that he has led India’s national resurgence. Under Modi, they note, India

has surpassed its former ruler, the United Kingdom, to become the world’s

fifth-largest economy; it will soon eclipse Japan and Germany, as well. It

became the fourth country to land a spaceship on the moon. But Modi’s impact

runs deeper than material achievements. His supporters proudly boast that India

has rediscovered and reaffirmed its Hindu civilizational roots, leading to a

successful decolonizing of the mind—a truer independence than even the freedom

movement led by Mahatma Gandhi achieved. The prime minister’s speeches are

peppered with claims that India is on the cusp of leading the world. In pursuit

of its global ambitions, his government hosted the G-20 meeting in New Delhi

last year, the event carefully choreographed to show Modi in the best possible

light, standing splendidly alone at center stage as one by one, he welcomed world

leaders, including U.S. President Joe Biden, and showed them to their

seats. (The party was spoiled, only slightly, by the deliberate absence of the

Chinese leader Xi Jinping, who may not have wanted to indulge Modi in his

pageant of prestige.)

Nonetheless, the

future of the Indian republic looks considerably less rosy than the vision

promised by Modi and his acolytes. His government has not assuaged—indeed, it

has actively worked to intensify—conflicts along lines of both religion and

region, which will further fray the country’s social fabric. The inability or

unwillingness to check environmental abuse and degradation threatens public

health and economic growth. The hollowing out of democratic institutions pushes

India closer and closer to becoming a democracy only in name and an electoral

autocracy in practice. Far from becoming the Vishwa Guru, or “teacher to the

world”—as Modi’s boosters claim—India is altogether more likely to remain what

it is today: a middling power with a vibrant entrepreneurial culture and mostly

fair elections alongside malfunctioning public institutions and persisting

cleavages of religion, gender, caste, and region. The façade of triumph and

power that Modi has erected obscures a more fundamental truth: that a principal

source of India’s survival as a democratic country, and of its recent economic

success, has been its political and cultural pluralism, precisely those

qualities that the prime minister and his party now seek to extinguish.

Portrait In Power

Between 2004 and

2014, India was run by Congress-led coalition governments. The prime minister

was the scholarly economist Manmohan Singh. By the end of his second term,

Singh was 80 and unwell, so the task of running Congress’s campaign ahead of

the 2014 general elections fell to the much younger Rahul Gandhi. Gandhi is the

son of Sonia Gandhi, a former president of the Congress Party, and Rajiv

Gandhi, who, like his mother, Indira Gandhi, and grandfather Nehru, had served

as prime minister. In a brilliant political move, Modi, who had previously been

chief minister of the important state of Gujarat

for a decade, presented himself as an experienced, hard-working, and entirely

self-made administrator, in stark contrast to Rahul Gandhi, a dynastic scion

who had never held political office and whom Modi portrayed as entitled and

effete.

Sixty years of

electoral democracy and three decades of market-led economic growth had made Indians

increasingly distrustful of claims made based on family lineage or privilege.

It also helped that Modi was a more compelling orator than Rahul Gandhi and

that the BJP made better use of the new media and digital technologies to reach

remote corners of India. In the 2014 elections, the BJP won 282 seats, up from

116 five years earlier, while the Congress’s tally went down from 206 to a mere

44. The next general election, in 2019, again pitted Modi against Gandhi; the

BJP won 303 seats to the Congress’s 52. With these emphatic victories, the BJP

not only crushed and humiliated the Congress but also secured the legislative

dominance of the party. In prior decades, Indian governments had typically been

motley coalitions held together by compromise. The BJP’s healthy majority under

Modi has given the prime minister broad latitude to act—and free rein to pursue

his ambitions.

Modi presents himself

as the very embodiment of the party, the government, and the nation, as almost

single-handedly fulfilling the hopes and ambitions of Indians. In the past

decade, his elevation has taken many forms, including the construction of the world’s

largest cricket stadium, named for Modi; the portrait of Modi on

the COVID-19 vaccination certificates issued by the government of

India (a practice followed by no other democracy in the world); the photo of

Modi on all government schemes and welfare packages; a serving judge of the

Supreme Court gushing that Modi is a “visionary” and a “genius”; and Modi’s

proclamation that he had been sent by god to emancipate India’s women.

In keeping with this

gargantuan cult of personality, Modi has attempted, largely successfully, to

make governance and administration an instrument of his will rather than a

collaborative effort in which many institutions and individuals work together.

In the Indian system, based on the British model, the prime minister is

supposed to be merely first among equals. Cabinet ministers are meant to have

relative autonomy in their spheres of authority. Under Modi, however, most

ministers and ministries take instructions directly from the prime minister’s

office and from officials known to be personally loyal to him. Likewise,

Parliament is no longer an active theater of debate, in which the views of the

opposition are taken into account in forging legislation. Many bills are passed

in minutes, by voice vote, with the speakers in both houses acting in an

extremely partisan manner. Opposition members of Parliament have been suspended

in the dozens—and in one recent case, in the hundreds—for demanding that the

prime minister and home minister make statements about such important matters

as bloody ethnic conflicts in India’s borderlands and security breaches in

Parliament itself.

Sadly, the Indian

Supreme Court has done little to stem attacks on democratic freedoms. In past

decades, the court had at least occasionally stood up for personal freedoms,

and the rights of the provinces, acting as a modest brake on the arbitrary

exercise of state power. Since Modi took office, however, the Supreme Court has

often given its tacit approval to the government’s misconduct, by, for example,

failing to strike down punitive laws that violate the Indian constitution. One

such law is the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, under which

it is almost impossible to get bail and which has been invoked to arrest and

designate as “terrorists” hundreds of students and human rights activists for

protesting peacefully on the streets against the majoritarian policies of the

regime.

The civil services

and the diplomatic corps are also prone to obey the prime minister and his

party, even when the demands clash with constitutional norms. So does the

Election Commission, which organizes elections and frames election rules to

facilitate the preferences of Modi and the BJP. Thus, elections in Jammu and

Kashmir and to the municipal council of Mumbai, India’s richest city, have been

delayed for years largely because the ruling party remains unsure of winning

them.

The Modi government

has also worked systematically to narrow the spaces open for democratic

dissent. Tax officials disproportionately target opposition politicians. Large

sections of the press act as the mouthpiece of the ruling party for fear of

losing government advertisements or facing vindictive tax raids. India

currently ranks 161 out of 180 countries surveyed in the World

Press Index, an analysis of levels of journalistic freedom. Free debate in

India’s once vibrant public universities is discouraged; instead, the

University Grants Commission has instructed vice-chancellors to install “selfie

points” on campuses to encourage students to take their photograph with an

image of Modi.

This story of the

systematic weakening of India’s democratic foundations is increasingly

well-known outside the country, with watchdog groups bemoaning the backsliding

of the world’s largest democracy. But another fundamental challenge to India

has garnered less attention: the erosion of the country’s federal structure.

India is a union of states whose constituent units have their governments

elected based on universal adult franchise. As laid down in India’s

constitution, some subjects, including defense, foreign affairs, and monetary

policy, are the responsibility of the government in New Delhi. Others,

including agriculture, health, and law and order, are the responsibility of the

states. Still others, such as forests and education, are the joint responsibility

of the central government and the states. This distribution of powers allows

state governments considerable latitude in designing and implementing policies

for their citizens. It explains the wide variation in policy outcomes across

the country—why, for example, the southern states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu have

a far better record about health, education, and gender equity compared with

northern states such as Uttar Pradesh.

A Modi supporter in Ayodhya, India, December 2023

As a large, sprawling

federation of states, India resembles the United States. But India’s states are

more varied in terms of culture, religion, and particularly language. In that

sense, India is more akin to the European Union in the continental

scale of its diversity. The Bengalis, the Kannadigas, the Keralites, the Odias, the Punjabis, and the Tamils, to name just a few

peoples, all have extraordinarily rich literary and cultural histories, each

distinct from one another and especially from that of the heartland states of

northern India where the BJP is dominant. Coalition governments respected and

nourished this heterogeneity, but under Modi, the BJP has sought to compel

uniformity in three ways: through imposing the main language of the north,

Hindi, in states where it is scarcely spoken and where it is seen as an

unwelcome competitor to the local language; through promoting the cult of Modi

as the only leader of any consequence in India; and through the legal and

financial powers that being in office in New Delhi bestows on it.

Since coming to

power, the Modi government has assiduously undermined the autonomy of state

governments run by parties other than the BJP. It has achieved this in part

through the ostensibly nonpartisan office of the governor, who, in states not

run by the BJP, has often acted as an agent of the ruling party in New Delhi.

Laws in domains such as agriculture, nominally the realm of state governments,

have been passed by the national Parliament without the consultation of the

states. Since several important and populous states—including Kerala, Punjab,

Tamil Nadu, Telangana, and West Bengal—are run by popularly elected parties

other than the BJP, the Modi government’s undisguised hostility toward their

autonomous functioning has created a great deal of bad blood.

In this manner, in

his decade in office, Modi has worked diligently to centralize and personalize

political power. As chief minister of Gujarat, he gave his cabinet colleagues

little to do, running the administration through bureaucrats loyal to him. He also

worked persistently to tame civil society and the press in Gujarat. Since Modi

became prime minister in 2014, this authoritarian approach to governance has

been carried over to New Delhi. His authoritarianism has a precedent, however:

the middle period of Indira Gandhi’s prime ministership,

from 1971 to 1977, when she constructed a cult of personality and turned the

party and government into an instrument of her will. But Modi’s subordination

of institutions has gone even further. In his style of administration, he is

Indira Gandhi on steroids.

A Hindu Kingdom

For all their

similarities in political style, Indira Gandhi and Modi differ markedly in

terms of political ideology. Forged in the crucible of the Indian freedom

struggle, inspired by the pluralistic ethos of its leader Mahatma Gandhi (who

was not related to her), and of her father, Nehru, Indira Gandhi was deeply

committed to the idea that India belonged equally to citizens of

all faiths. For her, as for Nehru, India was not to be a Hindu version of Pakistan—a

country designed to be a homeland for South Asia’s Muslims. India would not

define statecraft or governance by the views of the majority religious

community. India’s many minority religious groups—including Buddhists,

Christians, Jains, Muslims, Parsis, and Sikhs—would all have the same status

and material rights as Hindus. Modi has taken a different view. Raised as he

was in the hardline milieu of the Hindu nationalist movement, he sees the

cultural and civilizational character of India as defined by the demographic

dominance—and long-suppressed destiny—of Hindus.

The attempt to impose

Hindu hegemony on India’s present and future has two complementary elements.

The first is electoral, the creation of a consolidated Hindu vote bank.

Hinduism does not have the singular structure of Abrahamic religions such as

Christianity or Islam. It does not elevate one religious text (such as the

Bible or the Koran) or one holy city (such as Rome or Mecca) to a particularly

privileged status. In Hinduism, there are many gods, many holy places, and many

styles of worship. But while the ritual universe of Hinduism is pluralistic,

its social system is historically highly unequal, marked by hierarchically

organized status groups known as castes, whose members rarely intermarry or

even break bread with one another.

The BJP under Modi

has tried to overcome the pluralism of Hinduism by seeking to override caste

and doctrinal differences between different groups of Hindus. It promises to

construct a “Hindu Raj,” a state in which Hindus will reign supreme. Modi

claims that before his ascendance, Hindus had suffered 1,200 years of slavery

at the hands of Muslim rulers, such as the Mughal dynasty, and Christian

rulers, such as the British—and that he will now restore Hindu pride and Hindu

control over the land that is rightfully theirs. To aid this consolidation,

Hindu nationalists have systematically demonized India’s large Muslim minority,

painting Muslims as insufficiently apologetic for the crimes of the Muslim

rulers of the past and as insufficiently loyal to the India of the present.

Hindutva

Hindutva, or Hindu nationalism, is a belief

system characterized by what I call “paranoid triumphalism.” It aims to make

Hindus fearful to compel them to act together and ultimately dominate those

Indians who are not Hindus. At election time, the BJP hopes to make Hindus vote

as Hindus. Since Hindus constitute roughly 80 percent of the population, if 60

percent of them vote principally based on their religious affiliation in

India’s multiparty, first-past-the-post system, that amounts to 48 percent of

the popular vote for the BJP—enough to get Modi and his party elected by a

comfortable margin. Indeed, in the 2019 elections, the BJP won 56 percent of

seats with 37 percent of the popular vote. So complete is the ruling party’s

disregard for the political rights of India’s 200 million or so Muslims that,

except when compelled to do so in the Muslim-majority region of Kashmir, it

rarely picks Muslim candidates to compete in elections. And yet it can still

comfortably win national contests. The BJP has 397 members in the two houses of

the Indian parliament. Not one is a Muslim.

Electoral victory has

enabled the second element of Hindutva—the provision of an explicitly Hindu

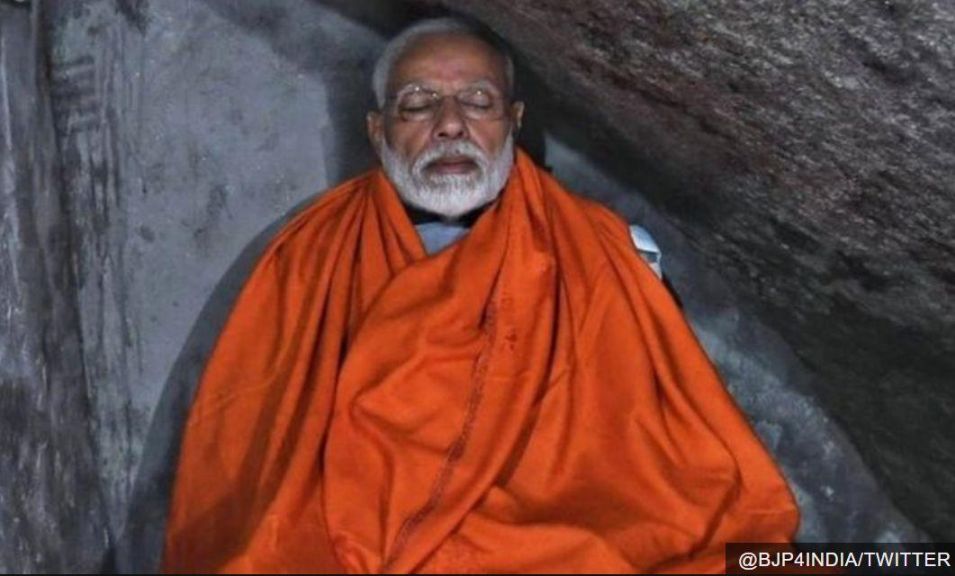

veneer to the character of the Indian state. Modi himself chose to contest the

parliamentary elections from Varanasi, an ancient city with countless temples

that is generally recognized as the most important center of Hindu identity. He

has presented himself as a custodian of Hindu traditions, claiming that in his

youth, he wandered and meditated in the forests of the Himalayas in the manner

of the sages of the past. He has, for the first time, made Hindu rituals

central to important secular occasions, such as the inauguration of a new

Parliament building, which was conducted by him alone, flanked by a phalanx of

chanting priests, but with the members of Parliament, the representatives of

the people, conspicuously absent. He also presided, in a similar fashion, over

religious rituals in Varanasi, with the priests chanting, “Glory to the king.”

In January, Modi was once again the star of the show as he opened a large

temple in the city of Ayodhya on a site claimed to be the birthplace of the god

Rama. Whenever television channels obediently broadcast such proceedings live

across India, their cameras focus on the elegantly attired figure of Modi. The

self-proclaimed Hindu monk of the past has thus become, in symbol if not in

substance, the Hindu emperor of the present.

The Burdens Of The Future

The emperor benefits

from having few plausible rivals. Modi’s enduring political success is in part

enabled by a fractured and nepotistic opposition. In a belated bid to stall the

BJP from winning a third term, as many as 28 parties have come together to

fight the forthcoming general elections under a common umbrella. They have

adopted the Indian National Development Inclusive Alliance, an unwieldy moniker

that can be condensed to the crisp acronym INDIA.

Some parties in this

alliance are very strong in their states. Others have a base among particular

castes. But the only party in the alliance with pretensions to being a national

party is the Congress. Despite his dismal political record, Rahul Gandhi remains

the principal leader of the Congress. In public appearances, he is often

flanked by his sister, who is the party’s general secretary, or his mother,

reinforcing his sense of entitlement. The major regional parties, with

influence in states such as Bihar, Maharashtra, and Tamil Nadu, are also family

firms, with leadership often passing from father to son. Although their local

roots make them competitive in state elections, when it comes to a general

election, the dynastic baggage they carry puts them at a distinct disadvantage

against a party led by a self-made man such as Modi, who can present himself as

devoted entirely and utterly to the welfare of his fellow citizens rather than

as the bearer of family privilege. INDIA will struggle to unseat Modi and the

BJP and may hope, at best, to dent their commanding majority in Parliament.

The prime minister

also faces little external pressure. In other contexts, one might expect a

certain amount of critical scrutiny of Modi’s authoritarian ways from the

leaders of Western democracies. But this has not happened, partly because of

the ascendance of the Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

Xi has mounted an aggressive challenge to Western hegemony and positioned China

as a superpower deserving equal respect and an equal say in world affairs as

the United States—moves that have worked entirely to Modi’s advantage. The

Indian prime minister has played the U.S. establishment brilliantly, using the

large and wealthy Indian diaspora to make his (and India’s) importance visible

to the White House.

In April 2023, India

officially overtook China as the most populous country in the world. It has the

fifth-largest economy. It has a large and reasonably well-equipped military.

All these factors make it even more appealing to the United States as a counterweight

to China. Both the Trump and the Biden administrations have shown extraordinary

indulgence toward Modi, continuing to hail him as the leader of the “world’s

largest democracy” even as that appellation becomes less credible under his

rule. The attacks on minorities, the suppression of the press, and the arrest

of civil rights activists have attracted scarcely a murmur of disapproval from

the State Department or the White House. The recent allegations that the Indian

government tried to assassinate a U.S. citizen of Sikh descent are likely to

fade without any action or strong public criticism. Meanwhile, the leaders

of France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, seeking a greater share

of the Indian market (not least in sales of sophisticated weaponry), have all

been unctuous in their flattery of Modi.

In the old quarters of Delhi, January 2024

Currently, Modi is

dominant at home and immune from criticism from abroad. It is likely, however,

that history and historians will judge his political and personal legacy

somewhat less favorably than his currently supreme position might suggest. For

one thing, he came into office in 2014 pledging to deliver a strong economy,

but his economic record is at best mixed. On the positive side, the government

has sped the impressive development of infrastructure and the process of

formalizing the economy through digital technology. Yet economic inequalities

have soared; while some business families close to the BJP have become

extremely wealthy, unemployment rates are high, particularly among young

Indians, and women’s labor participation rates are low. Regional disparities

are large and growing, with the southern states having done far better than the

northern ones in terms of both economic and social development. Notably, none

of the five southern states are ruled by the BJP.

The rampant environmental

degradation across the country further threatens the sustainability of

economic growth. Even in the absence of climate change, India would be an

environmental disaster zone. Its cities have the highest rates of air pollution

in the world. Many of its rivers are ecologically dead, killed by untreated

industrial effluents and domestic sewage. Its underground aquifers are

depleting rapidly. Much of its soil is contaminated with chemicals. Its forests

are despoiled and in the process of becoming much less biodiverse, thanks to

invasive non-native weeds.

This degradation has

been enabled by an antiquated economic ideology that adheres to the mistaken

belief that only rich countries need to behave responsibly toward nature.

India, it is said, is too poor to be green. Countries such as India, with their

higher population densities and more fragile tropical ecologies, need to care

as much, or more, about how to use natural resources wisely. But regimes led by

both Congress and the BJP have granted a free license to coal and petroleum

extraction and other polluting industries. No government has so actively

promoted destructive practices as Modi’s. It has eased environmental clearances

for polluting industries and watered down various regulations. The

environmental scholar Rohan D’ Souza has written that by 2018, “the slash and

burn attitude of gutting and weakening existing environmental institutions,

laws, and norms was extended to forests, coasts, wildlife, air, and even waste

management.” When Modi came to power in 2014, India ranked 155 out of 178

countries assessed by the Environmental Performance Index, which estimates the

sustainability of a country’s development in terms of the state of its air,

water, soils, natural habitats, and so on. By 2022, India ranked last, 180 out

of 180.

The effects of these

varied forms of environmental deterioration exact a horrific economic and

social cost on hundreds of millions of people. Degradation of pastures and

forests imperils the livelihoods of farmers. Unregulated mining for coal and

bauxite displaces entire rural communities, making their people ecological

refugees. Air pollution in cities endangers the health of children, who miss

school, and of workers, whose productivity declines. Unchecked, these forms of

environmental abuse will impose ever-greater burdens on Indians yet unborn.

These future

generations of Indians will also have to bear the costs of the dismantling of

democratic institutions overseen by Modi and his party. A free press,

independent regulatory institutions, and an impartial and fearless judiciary

are vital for political freedoms, for acting as a check on the abuse of state

power, and for nurturing an atmosphere of trust among citizens. To create, or

perhaps more accurately, re-create, them after Modi and the BJP finally

relinquish power will be an arduous task.

The strains placed on

Indian federalism may boil over in 2026, when parliamentary seats are scheduled

to be reallocated according to the next census, to be conducted in that year.

Then, what is now merely a divergence between north and south might become an

actual divide. In 2001, when a reallocation of seats based on population was

proposed, the southern states argued that it would discriminate against them

for following progressive health and education policies in prior decades that

had reduced birth rates and enhanced women’s freedom. The BJP-led coalition

government then in power recognized the merits of the south’s case and, with

the consent of the opposition, proposed that the reallocation be delayed for a

further 25 years.

In 2026, the matter

will be reopened. One proposed solution is to emulate the U.S. model, in which

congressional districts reflect population size while each state has two seats

in the Senate, irrespective of population. Perhaps having the Rajya Sabha, or

upper house, of the Indian Parliament restructured on similar principles may

help restore faith in federalism. But if Modi and the BJP are in power, they

will almost certainly mandate the process of reallocation based on population

in both the Lok Sabha, the lower house, and the Rajya Sabha, which will then

substantially favor the more populous if economically lagging states of the

north. The southern states are bound to protest. Indian federalism and unity

will struggle to cope with the fallout.

If the BJP achieves a third successive electoral

victory in May, the creeping majoritarianism under Modi could turn into

galloping majoritarianism, a trend that poses a fundamental challenge to Indian

nationhood. Democratic- and pluralistic-minded Indians warn of the dangers of

India becoming a country like Pakistan, defined by religious identity. A more

salient cautionary tale might be Sri Lanka’s. With its educated population,

good health care, relatively high position of women (compared with India and

all other countries in South Asia), its capable and numerous professional

class, and its attractiveness as a tourist destination, Sri Lanka was poised in

the 1970s to join Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan as one of the so-called

Asian Tigers. But then, a deadly mix of religious and linguistic

majoritarianism reared its head. The Sinhala-speaking Buddhist majority chose

to consolidate itself against the Tamil-speaking minority, who were themselves

largely Hindus. Through the imposition of Sinhalese as the official language

and Buddhism as the official religion, a deep division was created, provoking

protests by the Tamils, peaceful at first but increasingly violent when crushed

by the state. Three decades of bloody civil war ensued. The conflict formally

ended in 2009, but the country has not remotely recovered, in social, economic,

political, or psychological terms.

Modi speaking in New Delhi, January 2024

India will probably

not go the way of Sri Lanka. A full-fledged civil war between Hindus and

Muslims, or between north and south, is unlikely. But the Modi government is

jeopardizing a key source of Indian strength: its varied forms of pluralism. One

might usefully contrast Modi’s time in office with the years between 1989 and

2014 when neither the Congress nor the BJP had a majority in Parliament. In

that period, prime ministers had to bring other parties into government,

allocating important ministries to its leaders. This fostered a more inclusive

and collaborative style of governance, more suitable to the size and diversity

of the country itself. States run by parties other than the BJP or the Congress

found representation at the center, their voices heard and their concerns taken

into account. Federalism flourished, and so did the press and the courts, which

had more room to follow an independent path. It may be no coincidence that it

was in this period of coalition government that India experienced three decades

of steady economic growth.

When India became

free from British rule in 1947, many skeptics thought it was too large and too

diverse to survive as a single nation and its population too poor and

illiterate to be trusted with a democratic system of governance. Many predicted

that the country would Balkanize, become a military dictatorship, or experience

mass famine. That those dire scenarios did not come to pass was largely because

of the sagacity of India’s founding figures, who nurtured a pluralist ethos

that respected the rights of religious and linguistic minorities and who sought

to balance the rights of the individual and the state, as well as those of the

central government and the provinces. This delicate calculus enabled the

country to stay united and democratic and allowed its people to steadily

overcome the historic burdens of poverty and discrimination.

The last decade has

witnessed the systematic erosion of those varied forms of pluralism. One party,

the BJP, and within it, one man, the prime minister, are judged to represent

India to itself and the world. Modi’s charisma and popular appeal have consolidated

this dominance, electorally speaking. Yet the costs are mounting. Hindus impose

themselves on Muslims, the central government imposes itself on the provinces,

and the state further curtails the rights and freedoms of citizens. Meanwhile,

the unthinking imitation of Western models of energy-intensive and

capital-intensive industrialization is causing profound and, in many cases,

irreversible environmental damage.

Modi and the BJP seem

poised to win their third general election in a row. This victory would further

magnify the prime minister’s aura, enhancing his image as India’s redeemer. His

supporters will boast that their man is assuredly taking his country toward

becoming the Vishwa Guru, the teacher to the world. Yet such triumphalism

cannot mask the deep fault lines underneath, which—unless recognized and

addressed—will only widen in the years to come.

For updates click hompage here