By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Today, India’s prime minister’s annual Independence Day speech

reflected how

far political discourse has fallen in New Delhi.

Before his speech, PM Modi hoisted the ‘Tiranga’

at the iconic Red Fort in New Delhi. This was also Prime Minister's ninth

Independence Day address to the nation from the Red Fort.

PM Modi hereby sported a Tricolour-themed

turban for Independence Day, imbibing the ‘Har Ghar Tiranga’ spirit. If we look back, one notices that, unlike

prior revolutions, India’s split from the British Empire came about through a

political movement committed to nonviolence. The Indian National Congress, led

by Mahatma Gandhi, organized peaceful demonstrations on an unprecedented

scale. The mighty British Empire ultimately capitulated, encouraging

anticolonial movements worldwide.

India has long commemorated this watershed moment on Aug. 15, headlined

by the prime minister’s speech on the ramparts of the Red Fort in New Delhi.

Leaders traditionally set aside partisan rivalries in these speeches, focusing on

apolitical themes: the importance of Gandhi and the nonviolence movement, the

resilience of India’s democracy, and the importance of tolerance and inclusion.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has mostly stuck to this formula, but this

year’s speech signaled how Modi is trying to redefine what it means to be an

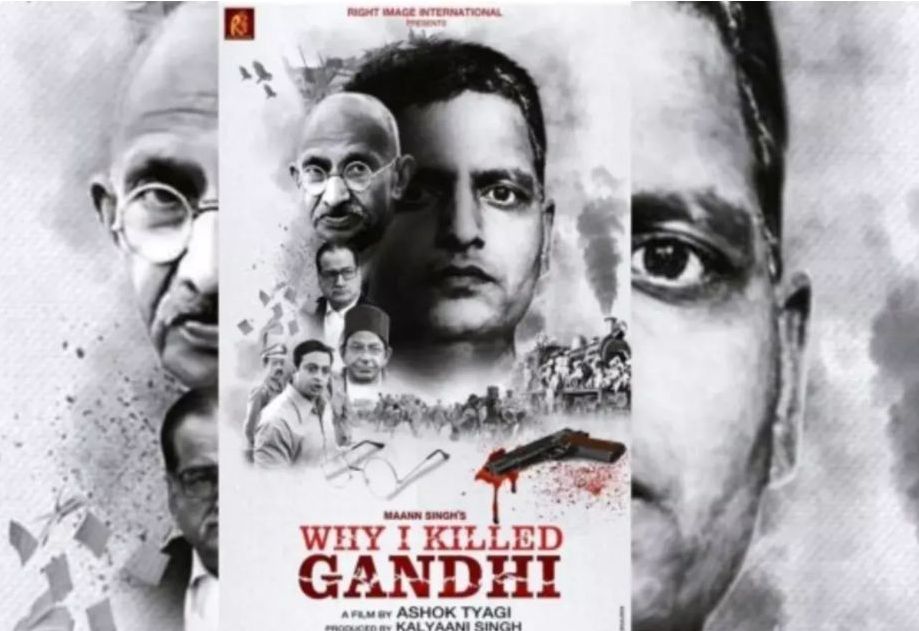

Indian. Gradually moving away from what was pointed out in Why I killed Gandhi.

The RSS is an organization like a private army. This was also

illuminated by James Crabtree’s 2018 book “The Billionaire Raj: A Journey

Through India’s New Gilded Age,” where, during an interview with Crabtree,

Modi’s brother Prahlad the latter recalls that Modi

started on his current path as a full-time volunteer and lived in the Ahmedabad

headquarters of the RSS where he went “very deep into the RSS and its works of

nation-building and patriotism” and “decided to dedicate his life to that.” (1)

Modi then set up a unit of the RSS’s students’ wing, the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, after which, Modi rose

steadily in the RSS hierarchy, and his association with the organization

significantly benefited his subsequent political career.

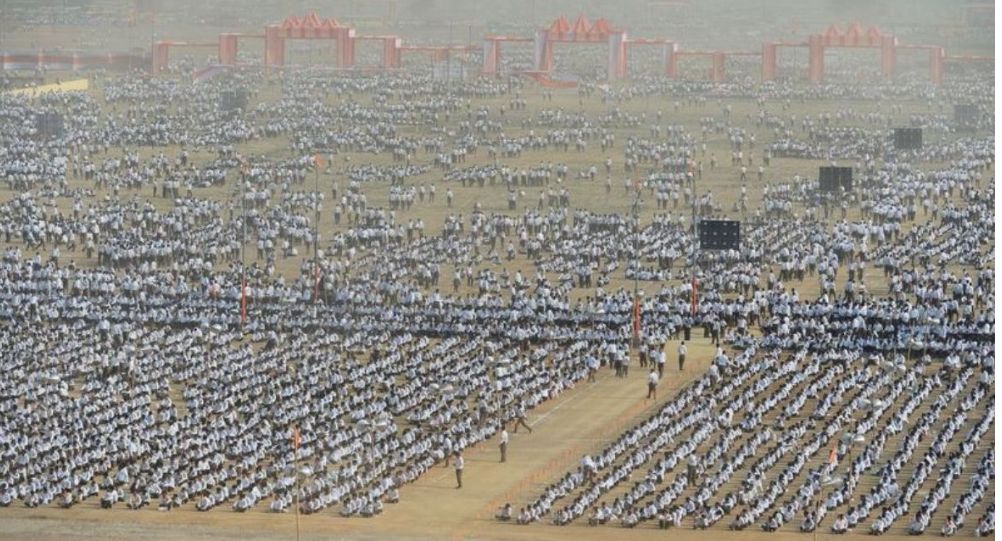

Underneath Volunteers of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak

Sangh (RSS). gather for a large-scale congregation in Meerut.

According to Walter K. Andersen and Shridhar D. Damle,

the RSS sought to draw upon the dense network of mutts, ashrams, and other

organizations of monastic orders to develop political Hinduism. (2)With the

gradual rise of the BJP, Muslims are particularly marginalized politically and

pushed out of public institutions such as the police and the judiciary. Muslims

hold just 4 percent of seats in the outgoing parliament, down from a peak of 9.6

percent in 1980. During Modi’s first term, expressions of anti-Muslim hatred

have grown more common and acceptable in public life.

One symptom of this is a growing number of lynchings of Muslims concerning

cows, animals considered sacred by orthodox Hindus. In September 2015,

a Muslim laborer, Mohammad Akhlaq, was murdered

by his neighbors in a village outside New Delhi on suspicion of eating beef.

Afterward, officials seized meat samples from the victim’s home to determine if

it was beef, which extremists argued would be a mitigating factor in his

killing.

Between May 2015 and December 2018, at least 44 people, 36 Muslims,

were killed across 12 Indian states. Over that same period, around 280

people were injured in over 100 different incidents across 20 states.

Earlier on 28 May 2020, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Vice President M

Venkaiah Naidu, and others paid tributes to Vinayak Damodar Savarkar,

who popularized the term Hindutva. Today exemplified by Modi Savarkar, is loved

by the Hindu right with centrists and Muslims, Sikhs, Jains, and

Buddhists, in India, not to mention Kashmir, having a different

opinion.

A key conclusion from this analysis is that Hindu nationalist ideas

about identity, culture, and politics draw on and, to some extent, reflect the

construction of ideas about the Indian nation and its cultural heritage in the

late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Nevertheless, I have suggested that

the use of formulas and explicit religious symbols to draw the boundaries of

national identity may be construed as distinctive. Two lines of thought, the

obsessive concern with conversion and the aggressive assertion of ownership

over sites projected as sacred - indicate this distinctiveness.

Yet even here, there is a degree of embeddedness in broader fields of

thought. Perhaps the clearest post-independence example of this point is the

restoration of the Somnath temple in 1947/8.

Conversion issues also indicate a broader reach for ideas associated

with Hindu nationalism than the formal organizations of the Sangh Parivar.

Like Savarkar's Hindutva, Godse's self-justification sees recent events

against the backdrop of centuries of "Muslim tyranny" in India,

punctuated by the heroic resistance of Shivaji, the Hindu emperor. He carried

on a military campaign against the Moghul rulers in the eighteenth century with

brief success. Like Savarkar, he describes his goal as creating a strong, proud

India that can throw off centuries of domination.

Ripping up this vision of Gandhi was an important part of Savarkar's

politics. Only then could he have thought of making his politics succeed.

Savarkar had some advantages. The vision he espoused was easy to convey to

those who shared his obsession with Brahmin ascendency in politics, projecting

Muslims as enemies of their faith-based nationalism to unite various castes of Hindus without

altering the hegemony of the traditional social elite.

Members of the RSS (the parent organization of Vishwa Hindu Parishad) and

prominent Hindu thinkers in India and abroad were reportedly invited to Mumbai

(then Bombay) in India in August 1964. According to published reports, it was

decided that a new organization named Vishwa Hindu Parishad would be formed and

launched two years later, in 1966, at a world convention of Hindus.

Soon after its inception, the VHP focused on the Ramjanmbhoomi (birthplace of Lord Ram) issue in Ayodhya, India. Hindu extremists allege that the Babri

mosque is built in Ayodhya, in the western state

of Uttar Pradesh, is the birthplace of Lord

Ram (a revered Hindu God). Hindu fundamentalists, including the VHP, have

propagated that the Babri mosque is "replaced" by a Hindu temple of

Ram at the disputed site.

Later the RSS would support the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its chosen

representative after Prime Minister A. B. Vajpayee started his RSS organizer.

Today Godse is something of a hero on BJP and RSS

websites. Picturing the atmosphere at the time Nehru, believed that the murder

of Gandhi was part of a "fairly widespread conspiracy" on the part of

the Hindu right to seize power; he saw the situation as analogous to that in

Europe on the eve of the fascist takeovers. And he believed that the RSS was

the power behind this conspiracy.

Not surprisingly, in his speech, Modi ticked the boxes by mentioning Gandhi and his

commitment to inclusion, but he also departed from convention in essential

ways. First, he celebrated more than a dozen freedom fighters who had adopted a

violent approach to independence. These freedom fighters operated independently

of Gandhi and the Indian National Congress, undermining Gandhi and nonviolence

within India’s independence movement. By highlighting them in the speech, Modi

subtly rebelled against the conventional narrative and Gandhi’s central role.

Second, although Modi touched on inclusion regarding geography and

gender, he avoided mentioning secularism or religious tolerance. Instead, he

defined Indians as Hindus: “This is our legacy. How can we not be proud of this

heritage? We are those people who see Shiva [a main Hindu deity] in every

living being,” he said. “We are people who see the divine in the plants. We are

the people who consider the rivers as mothers. We are those people who see

Shankar [another form of Shiva] in every stone.” For India, a country with 280

million non-Hindu citizens that has struggled with religious tensions since its

founding, Modi’s religious interjections signal a break from the past.

Finally, Modi used the occasion to launch familiar jabs against the

opposition Indian National Congress party while overlooking critical challenges

facing the Indian state—including religious intolerance. He concluded his

speech by slamming people who defend corruption and by condemning nepotism. But

this was coded language that may sound like a threat to some Indian citizens:

Modi and his ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have

weaponized charges of corruption and nepotism to go after political opponents

and dissidents. Just days after Modi’s speech, his government conducted

an anticorruption

raid against Manish Sisodia, one of the prominent leaders of the

opposition Aam Aadmi Party.

Modi’s Independence Day speech is emblematic of a more significant

change under his rule, which has faced criticism for democratic

backsliding—moving away from the very constitution that came shortly after its

independence. The prime minister and the BJP are working to unshackle India

from its liberal and secular moorings, advancing a new national identity that

champions Hindu supremacy. This enterprise is antithetical to the very foundations of Hinduism, which is

an inherently pluralistic faith.

A750 sq ft National Flag was displayed at historical Lal Chowk by

Srinagar Sector CRPF. All civilians & force personnel came together to sing

the National anthem: Srinagar Sector CRPF:

Modi’s BJP government is also undercutting India’s institutions in

unprecedented ways. It has made a mockery of India’s rich tradition of civil

liberties by charging activists and dissidents with crimes under colonial-era

laws. One egregious example is the left-wing activists detained under the draconian

Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act for alleged links to Maoist groups and

allegedly fomenting riots. One of the accused, lifelong Jesuit activist Rev. Stan

Swamy, died in custody last year. Furthermore, Modi and the BJP have

co-opted much of the media and essential private sector actors. Journalists

have faced intimidation

and harassment; prominent nongovernmental organizations have been

cut off from foreign funding, while others can receive overseas money only into

accounts with a government-owned bank.

The 1947 Partition created two newly-independent

states - India and Pakistan - and triggered perhaps the most significant movement of people

in history, outside of war and famine. About 12 million

people became refugees. Between half a million and a million people were killed

in religious violence.

Not surprisingly, the most

critical lessons from the independence movement seem to be lost on India’s

contemporary leaders, as shown by their approach to religious pluralism and

democratic institutions. Although India’s leading revolutionaries were

committed to nonviolence, tensions between Hindus and Muslims marred the

independence movement. These tensions pulled the British Raj apart, and two new

countries emerged in its place: India and Pakistan. This week also marks the

anniversary of the Partition of India, which triggered one of the world’s worst humanitarian

disasters as Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs were forced to flee

in different directions across the new border. A few months later, India and

Pakistan went to war over the status of Jammu and Kashmir—a disagreement that

still plagues the subcontinent.

In the face of these tensions, India and Pakistan’s leaders charted

opposing courses. India’s leaders advanced a progressive and modern vision for

their new country, eschewing a national Hindu religion in favor of a secular

identity. They worked hard to minimize religious tensions by speaking against

communal strife and promoting religious protections. When Gandhi was

assassinated in 1948—for supposedly being a supplicant to the Muslim

community—his political heirs continued to push for a liberal vision of India.

Working with the opposition, they produced a constitution that enshrined a

liberal and secular democracy that remains in force today.

On the other hand, Pakistan struggled. The country’s founder, Muhammad

Ali Jinnah, led the Muslim League that split from the Indian National Congress.

But he was rarely straightforward in his vision for Pakistan: There is some

evidence that he wanted a secular state, but he also called for an

Islamic republic. When Jinnah died in 1948, he left behind a political mess.

Liaquat Ali Khan, Pakistan’s first prime minister, rejected amendments offered

by the opposition in his founding document, which became a precursor to the

country’s 1956 constitution that gave Islam, its pride of place in the project

of Pakistan. By turning to communalism, Pakistan has suffered as political

actors stir religious tensions to benefit their ends. Without credible

institutions or norms that allow political differences to be resolved, the

country cannot maintain political order.

1) James Crabtree, The Billionaire Raj: A Journey Through India’s New

Gilded Age, 2008, p. 123.

2) The Brotherhood in Saffron. The Rashtriya Swayamsevak

Sangh and Hindu Revivalism, 1987, p. 133.

For updates click hompage here