By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Modi’s Middling Economy

For an introduction

see also here and here. On

June 4, after counting roughly 650 million votes, the Election Commission of

India is scheduled to announce the winner of the 2024 parliamentary elections.

Polls suggest it will be the Bharatiya Janata Party,

led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. If the BJP is voted back to power after a

ten-year tenure, it would be a remarkable feat, driven largely by the prime

minister’s popularity. According to an April poll by Morning Consult, 76

percent of Indians approve of him.

There are multiple

theories for why Modi is so popular. Some attribute it to the fact that he has

advanced the “Hindutva” agenda, which views India from a Hindu-first lens.

Despite the periodic dog whistles against Muslims during the elections by Modi

and his lieutenants, this agenda is a primary electoral concern for only a

small fraction of India’s voters. In the 2019 elections, BJP’s vote share

nationally was less than 38 percent, and obviously, an even smaller share is

committed to the othering of religious minorities.

Another explanation

is that Modi has managed the economy well, with India recently overtaking the

United Kingdom to become the fifth-largest economy in the world, and soon

surpassing stagnant Germany and Japan to become the third-largest. His economic

stewardship, some experts argue, is setting up the country and its 1.4 billion

people to succeed in the future.

But India’s economic

growth, although seemingly high compared with other countries, has not been

large enough, or taken place in the right sectors, to create enough good jobs.

India is still a young country, and over ten million youth start looking for work

every year. When China and Korea were similarly young and poor, they employed

their growing labor force and consequently grew faster than India is today.

India, by contrast, risks squandering its population dividend. The joblessness,

especially among the middle class and lower-middle class, contributes to

another problem: a growing gulf between the prosperity of the rich and the

rest.

The Modi

administration has, of course, taken India forward in important ways, including

building out physical infrastructure (so that transportation is quicker) and

expanding digital infrastructure (so that payments are easier). Welfare

benefits, such as free food grains and gas cylinders, now reach beneficiaries

directly and without corruption. Startups abound, and Indian scientists and

engineers have scored notable successes, such as sending a satellite to Mars

and landing a rover on the moon’s south pole. Taken together, however, the last

decade has been decidedly a mixed economic bag for the average Indian.

Some of the

challenges India faces have been long in the making, but the administration’s

policies have also contributed in important ways. The government’s 2016 ban on

high value currency notes hurt small and mid-sized businesses, which were

further damaged by Modi’s mismanagement of the pandemic. Perhaps most

concerning is the government’s attempt to kick-start manufacturing through a

mix of subsidies and tariffs—a growth strategy modeled off of China—while

neglecting other development paths that would play to India’s strengths. The

Modi administration has, in particular, underinvested in improving the

capabilities of the country’s enormous population: the critical asset India

needs to navigate its future.

In the ongoing

election, the opposition has strived to highlight Indians’ economic anxiety.

But Modi is a charismatic and savvy politician, and he has established a strong

connection with ordinary Indians—in part by persuading them that his

administration has made India into a respected global power. Many Indians will

vote for him on the hope that he will eventually deliver progress, even if they

have not seen much improvement in the last decade. Others will vote for him

because of the government’s genuine success at efficiently delivering more

benefits. Still more will vote BJP because the mainstream media, largely

co-opted by the government, trumpets the government’s successes without

scrutinizing its failures.

India needs to change

economic course. That is less likely if the BJP wins with an overwhelming

majority because the party will see victory as an affirmation of its policies.

What is more worrying is that subsequent, growing authoritarianism—which shrinks

the space for protest and criticism—may continue to grow, and further diminish

the likelihood of a course correction. Conversely, if the election produces a

strong opposition, no matter its identity, India has a fighting chance of

securing the economic future its people desperately want.

A man pulling a cart in a wholesale market, Delhi,

January 2024

Mixed Bag

The Modi

administration’s forte has been implementation. It has continued, improved, and

expanded programs initiated by previous administrations. For instance, the

current government expanded the mandates established in the National Food

Security Act, which was enacted by the government of Prime Minister Manmohan

Singh—Modi’s predecessor. As a result, food grains were made free for over 800

million people during the pandemic. In a preelection move, the Modi

administration extended these benefits for another five years.

Singh’s government

also created “India Stack”: a digital framework that first gave each Indian a

unique ID and then overlaid multiple digital services onto it, including

payments. The BJP government expanded it to touch every Indian. Over 12 billion

digital payments took place in February 2024 using this architecture. These

included government transfers directly into the accounts of pensioners,

farmers, and women, eliminating the myriad middlemen who used to take a cut.

India is now helping countries across the developing world absorb and use the

architecture and technology underlying the India Stack.

Modi also deserves

credit for building out India’s infrastructure—particularly its roads, ports,

railway networks, and airports—faster than before. Once again, the rapid

expansion in highways and rural roads built on the Golden Quadrilateral

highways program and the Rural Roads Program initiated by the BJP government

under Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, who preceded Singh.

Modi’s government

also implemented some important policy initiatives that had long been

discussed. The Reserve Bank of India moved to an inflation-targeting framework

in 2016, which has helped contain price increases. That same year, a new

bankruptcy law facilitating debt resolution was finally enacted, and it has

helped banks recover money from defaulting borrowers. The Goods and Services

Tax, a value-added tax which unifies the Indian market by subsuming many state

and local taxes, was implemented in 2017.

Technology has also

improved people’s lives. The digital revolution has touched every Indian. Smart

phones are ubiquitous and data is cheap, allowing hundreds of millions of

people to come online. An ever-increasing number of government functions are

accessible online, simplifying and easing citizens’ experiences. The government

has also become more effective about communicating directly with the masses

about its programs. Roughly 230 million people tune in to the prime minister’s

monthly broadcast, and nearly a billion have listened at least once.

According to J.P.

Morgan, India will grow between 6 and 6.5 percent in this year and next, making

it the fastest-growing country in the G-20. But India’s per capita income is

$2,700, making it the poorest country in the G-20, and poor countries grow fast

because catch-up growth is easier. Moreover, the share of India’s population

that is of working age is increasing. The right growth benchmark for India is

therefore not that of developed, aging countries (which make up most of the

G-20) but the growth of large, successful emerging markets when they were at

India’s level of per capita income.

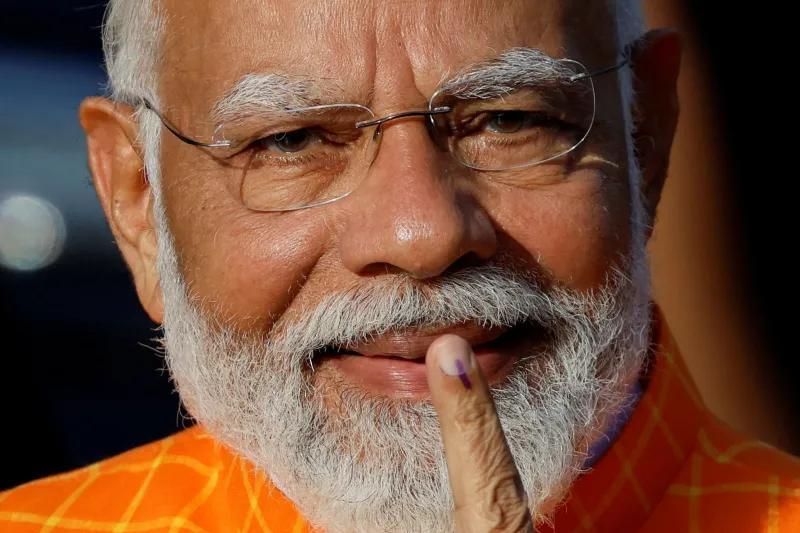

Modi after voting in Ahmedabad, India, May 2024

By this benchmark,

India has to do better. For instance, when China was at India’s per capita

level of GDP in the first decade of this century, before the global financial

crisis, it routinely grew at double-digit rates. Today, China is growing at

around five percent, even though its GDP per capita is nearly five times

India’s and its labor force has started shrinking. Put differently, if India

were to grow at its current pace for the next 25 years (which would itself be

an extraordinary feat), it would have a per capita income of around $10,000 in

today’s dollars—below where China is now.

India’s inadequate

pace of growth is most clearly visible in the lack of good jobs. The share of

jobs in India is growing in just two sectors: construction, partly as a result

of the government’s infrastructure push, and agriculture. The latter sector’s growth

is alarming. Usually, as countries develop, workers leave agriculture for

manufacturing and services, not the reverse. But even before the pandemic,

Indian workers have been going back into farming.

They do not seem to

be doing so eagerly. Most Indians would clearly prefer to work in white-collar

jobs, but there are simply not enough to go around. When the Indian state of

Madhya Pradesh posted openings for 6,000 low-level government revenue jobs in February

2023, it received more than 1.2 million applicants. Those applicants included

1,000 doctorates, 85,000 engineering college graduates, 100,000 business

administration graduates, and roughly 180,000 other people with postgraduate

degrees. The working-age population’s share in India is increasing. But it is

at risk of missing out on this population dividend because it cannot employ

them adequately.

Jobless Growth

Across the world,

fast-growing small and medium enterprises in labor-intensive sectors are

usually the primary source of private-sector jobs. But the last few years have

not been kind to them in India. Their woes began in 2016, when New Delhi

suddenly declared that bills representing 86 percent of India’s money stock

were no longer valid tender. Although Indians were allowed to deposit

“demonetized” notes in their banks up to a certain limit, not enough

replacement notes had been printed at the time of demonetization. The cash

transactions these firms typically relied on were upended for months. Some

businesses shuttered. Others were seriously weakened.

Then, seven months

later, the government reformed India’s Goods and Services Tax, dragging these

firms into the country’s tax net. This helped the government take in more

revenue, but it substantially altered the economics of these businesses. It

also imposed additional uncertainty and costs as they struggled to deal with

new filing requirements. Then came the pandemic. Although New Delhi offered

some assistance to indebted firms, they were largely left to fend for

themselves when the government imposed a long lockdown. As a result, even more

enterprises went out of business. Employment suffered accordingly.

With most households

worried about employment and incomes, domestic consumer demand for the output

produced by small and medium enterprises output has been soft. According to the

news portal Moneycontrol, 11 of the 23 categories of

manufacturing products that make up India’s Index of Industrial Production had

lower output in June 2023 than in June 2015. That includes the sectors

dominated by labor-intensive small firms, such as textiles, apparel, and leather

manufacturing.

Large Indian firms

are still doing well, taking market share ceded by small and medium

enterprises. Their growth is the reason the country’s GDP continues to tick up.

But these typically capital-intensive companies generate far more profits than

they do employment opportunities; they cannot hire India’s millions of

underemployed and unemployed citizens. Their stocks have gone up, boosting the

overall stock index (which is mostly composed of large businesses) and the

portfolios of the rich. But most Indians are not stock investors, so this does

little to help them.

The bifurcation of

the Indian economy between these two types of businesses—large and capital

intensive and small and labor intensive—is reflected more broadly in the lives

of Indians themselves. Rich Indians, many of whom are employed by big

companies, are doing exceptionally well. In the last fiscal year, for instance,

Mercedes-Benz recorded its highest-ever sales in India. According to a study by

a prominent group of economists, the top one percent of Indians earned 22.6

percent of the income in 2022–23, higher than the share in countries that are

considered grossly unequal, such as Brazil and South Africa.

But middle-class,

lower-middle-class, and poor Indians are hurting. Sales of the products they

use, such as motorized two-wheel vehicles, have yet to surpass pre-pandemic

levels. Similarly, sales by India’s largest mass-consumption goods producer,

Hindustan Unilever, have been muted, suggesting tepid consumption growth. Even

so, household savings have declined and household borrowing is at an all-time

high. With uncertain domestic demand, private investment to GDP is below where

it was in 2014, at the beginning of the Modi administration.

The Wrong Strategy

The Indian government

is trying to generate more economic activity, offering large subsidies to

manufacturing companies that set up shop in India. The government has also

raised tariffs on imported goods, such as cell phones, so that firms that make

in India get additional protected profits from selling into the Indian market.

But even as heavy subsidies to firms like Foxconn, which manufactures cell

phones for Apple, have generated jobs in the better-educated southern and

western states, India has lost market share in traditional exports such as

apparel, where India’s typically small, weakened firms have lost out to

exporters from Bangladesh and Vietnam. As a result, the total share of Indian

workers in manufacturing has not gone up over the last decade.

Even if the

government’s strategy attracts more manufacturing to India, it will eventually

run up against the reality that the world simply does not have enough consumers

to accommodate another China-sized manufacturing powerhouse, especially as

countries everywhere put up tariffs to protect their producers. And there is a

cost to the strategy. The heavy subsidies to manufacturing take away resources

that could be better utilized elsewhere. New Delhi, for example, is giving over

$2 billion in capital subsidies to get the U.S. tech company Micron to set up a

chip packaging and testing plant in the state of Gujarat—a plant that is

estimated to create only 5,000 jobs. The subsidies amount to more than

one-third of the central government’s entire higher education budget.

Education and

training are exactly the sorts of services the Indian government should be

spending more on. Doing so would enhance the quality of India’s human capital.

For instance, part of the reason that so many graduates are unemployed and

looking for government jobs is that their degrees are of low quality, which

means the private sector is not interested in hiring them. The survey firm Wheebox estimates 50 percent of Indian graduates are

unemployable—in that their degrees have not given them any skills employers

want.

There are steps the

government could take to help fix this issue. More training and apprenticeship

programs, for instance, might bring these graduates up to speed on the skills

that companies need, making more youth employable by companies at home or abroad—as

chip designers, engineers, consultants, legal advisers, and financial analysts.

More vocational programs could allow them to find profitable self-employment as

artisans, mechanics, plumbers, carpenters, and gardeners.

The reality is that

India’s greatest potential lies in its human capital. Graduates from India’s

top universities are comparable to those of the best Western universities but

cost a fraction of the amount for employers. These graduates are being hired by

multinational firms to design products, structure contracts, and develop

content and software that are embedded in manufactured goods and services sold

globally. There is a reason why Goldman Sachs has its biggest office outside of

New York in Bengaluru, with employees working in a variety of sectors,

including risk management, trading models, and actual trading. J.P. Morgan has

3,000 lawyers in India working on contracts around the world. India has 300,000

chip designers, even though the country does not produce a single chip. Such

activities now employ 3.2 million people in India and, according to a recent

study, generate $121 billion in annual revenue for the country.

Following the

pandemic-induced changes in work habits, and given improvements in

communications technology, Indians also have started providing a much wider

range of remote services, including consulting, telemedicine, and even yoga

instruction. Once a service goes virtual, it matters little whether the

provider is ten miles or 10,000 miles away. An Indian consultant in Hyderabad

can now make a presentation to a client in Seattle on behalf of a team whose

members span almost every continent. Add the services embedded in multinational

firm products together with direct service exports and India now accounts for

around five percent of worldwide trade in services. It accounts for less than

two percent of manufacturing.

An economy led by

services exports would follow a very different path from the

manufacturing-led-exports path the government desires. But the world has far

more room for the former. A service-providing India would also be more

sustainable for the climate than an India competing to make global manufactured

goods cheaper.

Thus far, services

exports have flourished without much help from the government. But the state

could do far more to improve the key raw material: the human capital of

Indians. Doing so requires enhancing the quality of child care, education,

skill training, and health care. An excellent government report detailing a new

and improved national education policy has sat on the shelf, largely

unimplemented. The government could also do more to negotiate new opportunities

for services exports—for example, by finding ways for national health insurance

systems in the West to allow and pay for telemedicine from India.

Reimagining India,

however, requires a departure from the manufacturing fetishism that currently

dominates government thinking, which echoes a global trend. With manufacturing

producing few jobs, the Modi administration cannot really say how it will fix the

current unemployment problem. And so the government simply refuses to

acknowledge it. A recent government white paper on the Indian economy does not

even mention the words “unemployment” or “underemployment.”

Life Of The Party

Despite his mixed

economic record, Modi, and by extension, his government, remains popular.

According to a 2023 poll by Pew, for example, 80 percent of Indian adults had a

favorable view of the prime minister. By some metrics, he is the most popular

leader in the world.

There are multiple

reasons for Modi’s high ratings among those who are not simply attracted by his

Hindutva agenda. One is that he has succeeded at convincing ordinary Indians

that he is responsible for the good things that happen to them. Unlike Singh, who

is a technocratic economist, Modi has ensured that Indians believe the benefits

they get, such as free grain or subsidized cooking gas, come directly from his

office. The BJP’s manifesto in this election is a testament to this, with the

prime minister’s name and picture plastered all over the document. This

personalization was also evident in the government’s response to the pandemic.

The program the government created to dole out aid was named “PM Cares.” Indian

vaccine certificates had the prime minister’s face on them. Such touches helped

Modi escape blame for his government's poor handling of the pandemic's second

wave, where hospitals across the country ran out of oxygen. The World Health

Organization, for example, estimates India’s excess deaths during the pandemic

at five million, the highest in the world and one of the highest ratios of

excess deaths to officially reported deaths in large economies.

Modi is able to

foster this connection in part because of his personal narrative. The child of

a railway tea seller, Modi went on to lead Gujarat and the country. To the

aspirational Indian, his trajectory is a source of admiration, inspiration, and

hope. The fact that Modi is not the scion of a political dynasty—unlike his

primary rival—has further helped his brand. That he has no immediate family to

promote gives him an image of personal incorruptibility.

News Outlets Bury Bad Economic News And Don’t Dwell On

Government Blunders.

The Modi image has

been somewhat dented by recent scandals. The BJP, for example, found itself in

hot water for allowing politicians with serious corruption charges from other

parties to join their ranks, with prosecutors then going slow or dropping the cases

against them. An Indian supreme court judgment on election financing also

revealed that businesses made donations to the BJP right before they received

government benefits or right after they were raided by government agencies.

But these scandals

can only hurt Modi so much, thanks to his success at coaxing and coercing the

press. In India, media outlets rely heavily on advertising from the government

and its companies, and when media outlets parrot the party line, they are rewarded

with ads and ministerial attendance at their lucrative business events. But if

outlets go off script, the carrots are pulled back. Instead, they can find tax

and investigative authorities at their doors. They may even have to fend off a

hostile takeover attempt by government-friendly businesses.

Consequently,

mainstream outlets have buried bad economic news and don’t dwell on government

blunders, such as demonetization or the poor response to COVID-19. They have

also given credit to Modi for positive developments that have more to do with

India’s growing prominence in the world and the West’s desire to use India as a

counter to China. When India hosted the annual G-20 summit in September 2023,

domestic media focused on virtually every minute of the meetings, staging shots

and providing commentary in ways that suggested the prime minister was at the

center of every important global decision, rather than being at the center

because India held the rotating presidency. There were certainly some

well-earned triumphs for New Delhi at the conference, which ended with a

statement of international consensus on difficult topics. Thanks to the media,

however, the ordinary voter could rationally believe the world thinks highly of

India because it thinks highly of Modi.

The prime minister

may not be able to sustain this image forever, despite the good marketing and

pliant press. The mismatch between the expectations of indebted graduates and

the jobs available is already fueling anxiety and conflict as different groups fight

for an expanded share of government jobs and university seats. (In India, large

swaths of public positions and college slots are reserved for disadvantaged

groups.) Voter interviews suggest that while they still believe in the prime

minister and are swayed by the efficient delivery of benefits, they do worry

about joblessness. But whatever voters decide, India needs both an economic and

democratic course correction, which only a strong opposition, regardless of its

identity, will bring.

For updates click hompage here