By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

A Modicum Of Restraint

U.S. contributions, however, come with strings attached.

Washington will try to preserve its interests, which demand restraint in the

targeting of nuclear facilities and oil infrastructure. Israeli interests

demand no such forbearance.

All signs, then,

point to a significant Israeli response. Iran has demonstrated its ability to

inflict damage on Israel, so Israel needs to demonstrate that it can inflict

even more damage on Iran. (Thus is the nature of escalation.) The most

effective way to do so would be to hit Iran in its territory. It could, for

example, send multiple sorties to hit a small number of strategic targets with

a disproportionate force – similar to the strategy used to destroy Hezbollah

leader Hassan Nasrallah’s bunker in Lebanon. This kind of attack could inflict

enough damage to count as a win for Israel even if it fails to destroy the

target entirely. And it could be much more palatable for the U.S., which would

almost certainly be involved in or consulted on the operation. The U.S. could

set certain targets off limits to preserve its interests while maintaining its

relationship with Israel.

Knowing that a

counterattack is on the way, Iran is already considering its options. Tehran

has made it clear that any Israeli action will be met with action of its own.

Politically, the government is split between those who want to make peace with

the West, which could, in theory, restrain Israel, and those who want to

continue to resist. A massive Israeli strike on Iranian soil would eliminate

the possibility of any cease-fire talks, particularly those related to its

nuclear program, and empower those who favor escalation.

Even so, a direct

military attack on Israel would not be in Iran’s best interests. Besides the

fact that Tehran does not want to see the region thrown into all-out war, the

country faces several military constraints. Its navy does not have the

capability to navigate from the ports in the Persian Gulf to the Eastern

Mediterranean unopposed or without early intel warning of its adversaries'

movements. (The U.S. and Israel can easily target naval moves through the Red

Sea.) It has no ballistic missile submarines, and its surface power is limited.

And it cannot afford to redeploy naval assets closer to Israel since doing so

would leave vulnerable the strategic Strait of Hormuz.

Its air force is

similarly unequal to the task. Its fleet – its aging, non-stealth F-14s, F-4s,

Mig-29s and KC 700-class refueling tankers – cannot attack Israel directly.

Previous efforts to attack Israeli territory through ballistic missiles and

drones have failed to maximize damage thanks to Israel’s sophisticated air

defense systems. (Notably, earlier attacks, including the one on Oct. 1, were

often conducted for ancillary reasons – saving face, a show of force or a

reminder to its allies that Iran had not abandoned them – rather than to

inflict as much death and destruction as possible.)

An Iranian ground

assault is also unlikely. The Iranian military’s newest tank, for example, has

a range of 350 miles, with internal fuel bringing its internal capability range

to roughly just over 475 miles. The closest route from Tehran to the Syrian-Lebanese

border is roughly 1,120 miles. But even if Israel were in range, the cost and

complexity of fueling armor and men through terrain that necessarily passes

through other countries is utterly disqualifying. It would draw in other

countries, including the U.S. and potentially Turkey, and would leave Iran

unable to defend itself closer to home.

Tehran’s response,

then, will primarily be executed by its proxy groups in Iraq, Lebanon, the

Palestinian territories and Yemen. For Iran, this will involve supplying more

arms, intelligence, money, expertise and equipment to expand operations in

their respective areas of operation. Though some question the integrity of the

Iranian-proxy relationship, especially now that Hezbollah has taken such a

beating, the fact is that these groups have no recourse and no other patron

besides Iran to support them. Their loyalty intact – or at least bought off –

these groups can be used to open new fronts against Israel and its allies in

order to stretch the frontline. This would strain the IDF, which lacks the

manpower to fight multiple fronts. For Iran, using proxies also allows the

government to respond without actually attacking Israel directly.

Ultimately, Iran’s capabilities are less important to

the outcome of the conflict than the U.S.-Israeli relationship. The past year

may have tested their ties, but it has yet to fully break them. This means that

Washington will likely accept any Israeli response, which we believe will yield

some restraint, however small it may be. Israel’s ideal scenario is the

elimination of Iran. But an acceptable, second-best goal is to make certain the

anti-Israel factions are gone. Israel can't change the reality of Iran’s

existence, but perhaps it thinks it can change the way it interacts with Hamas

and Hezbollah.

The Israeli Security Cabinet convened on

Oct. 10 to decide how it will retaliate against Iran’s recent missile barrage.

There’s reason to believe it's retaliation could be severe: One day earlier,

Defense Minister Yoav Gallant warned that Israel’s response would be “lethal,

precise and above all surprising.” Whatever form it takes, Israel’s actions

could escalate the conflict and expand the battlefield throughout the Middle

East.

Two major factors are

shaping Israel’s response. The first is, at least from Israel’s perspective,

the existential nature of the war. For Jerusalem, the fight represents the

future of the country’s relationship with the Islamic and Arab worlds. That

relationship has shaped much of Israel’s short existence, wherein borders were

established and maintained largely through force against what the public sees

as enemies in every direction. The second is its ally in the United States.

Though formidable, the Israel Defense Forces by themselves lack the

capabilities to conduct a massive, sustained strike on Iran – let alone the

numbers to defend against counterattacks.

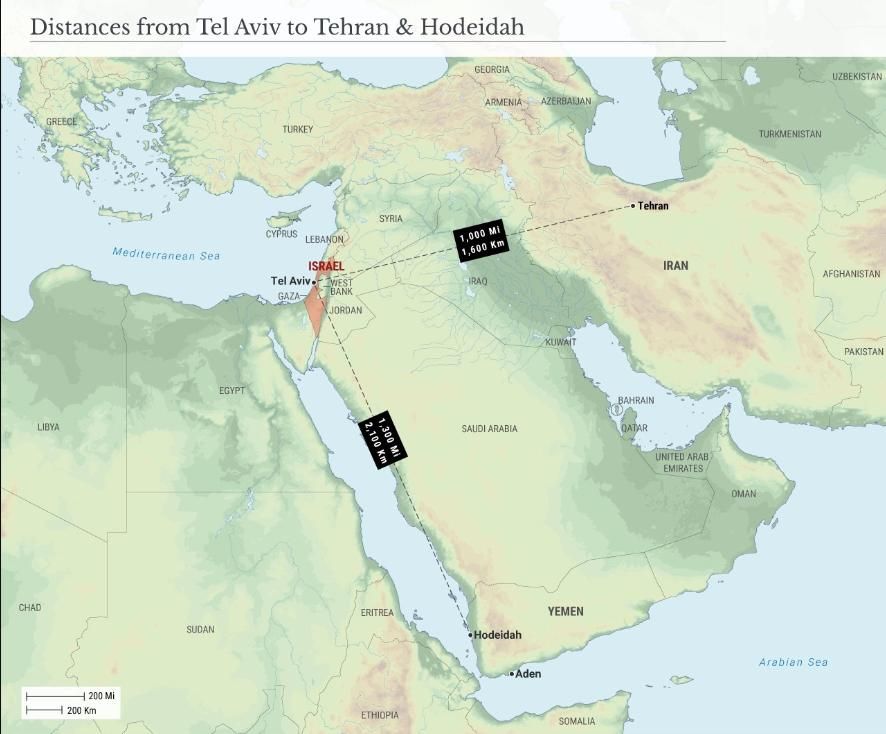

The IDF would have to

traverse Jordan and Syria to reach Tehran, with about 1,000 miles (1,600

kilometers) between Tel Aviv and Tehran. Covering that much ground would

require access to transit routes (ideally granted from other countries) and

refueling capabilities for aircraft, the latter of which is provided by the

United States. It therefore needs the financial and military assistance the

U.S. can bring to bear.

U.S. contributions,

however, come with strings attached. Washington will try to preserve its own

interests, which demand restraint in the targeting of nuclear facilities and

oil infrastructure. Israeli interests demand no such forbearance.

All signs, then,

point to a significant Israeli response. Iran has demonstrated its ability to

inflict damage on Israel, so Israel needs to demonstrate that it can inflict

even more damage on Iran. (Thus is the nature of escalation.) The most

effective way to do so would be to hit Iran in its own territory. It could, for

example, send multiple sorties to hit a small number of strategic targets with

a disproportionate force – similar to the strategy used to destroy Hezbollah

leader Hassan Nasrallah’s bunker in Lebanon. This kind of attack could inflict

enough damage to count as a win for Israel even if it fails to destroy the

target entirely. And it could be much more palatable for the U.S., which would

almost certainly be involved in or consulted on the operation. The U.S. could

set certain targets off limits to preserve its interests while maintaining its

relationship with Israel.

Knowing that a

counterattack is on the way, Iran is already considering its options. Tehran

has made it clear that any Israeli action will be met with action of its own.

Politically, the government is split between those who want to make peace with

the West, which could, in theory, restrain Israel, and those who want to

continue to resist. A massive Israeli strike on Iranian soil would eliminate

the possibility of any cease-fire talks, particularly those related to its

nuclear program, and empower those who favor escalation.

Even so, a direct

military attack on Israel would not be in Iran’s best interests. Besides the

fact that Tehran does not want to see the region thrown into all-out war, the

country faces several military constraints. Its navy does not have the

capability to navigate from the ports in the Persian Gulf to the Eastern

Mediterranean unopposed or without early intel warning of its adversaries'

movements. (The U.S. and Israel can easily target naval moves through the Red

Sea.) It has no ballistic missile submarines, and its surface power is limited.

And it cannot afford to redeploy naval assets closer to Israel since doing so

would leave vulnerable the strategic Strait of Hormuz.

Its air force is

similarly unequal to the task. Its fleet – its aging, non-stealth F-14s, F-4s,

Mig-29s and KC 700-class refueling tankers – cannot attack Israel directly.

Previous efforts to attack Israeli territory through ballistic missiles and

drones have failed to maximize damage thanks to Israel’s sophisticated air

defense systems. (Notably, earlier attacks, including the one on Oct. 1, were

often conducted for ancillary reasons – saving face, a show of force or a

reminder to its allies that Iran had not abandoned them – rather than to

inflict as much death and destruction as possible.)

An Iranian ground

assault is also unlikely. The Iranian military’s newest tank, for example, has

a range of 350 miles, with internal fuel bringing its internal capability range

to roughly just over 475 miles. The closest route from Tehran to the Syrian-Lebanese

border is roughly 1,120 miles. But even if Israel were in range, the cost and

complexity of fueling armor and men through terrain that necessarily passes

through other countries is utterly disqualifying. It would draw in other

countries, including the U.S. and potentially Turkey, and would leave Iran

unable to defend itself closer to home.

Tehran’s response,

then, will primarily be executed by its proxy groups in Iraq, Lebanon, the

Palestinian territories and Yemen. For Iran, this will involve supplying more

arms, intelligence, money, expertise and equipment to expand operations in

their respective areas of operation. Though some question the integrity of the

Iranian-proxy relationship, especially now that Hezbollah has taken such a

beating, the fact is that these groups have no recourse and no other patron

besides Iran to support them. Their loyalty intact – or at least bought off –

these groups can be used to open new fronts against Israel and its allies in

order to stretch the frontline. This would strain the IDF, which lacks the

manpower to fight multiple fronts. For Iran, using proxies also allows the

government to respond without actually attacking Israel directly.

Ultimately, Iran’s capabilities are less important to

the outcome of the conflict than the U.S.-Israeli relationship. The past year

may have tested their ties, but it has yet to fully break them. This means that

Washington will likely accept any Israeli response, which we believe will yield

some restraint, however small it may be. Israel’s ideal scenario is the

elimination of Iran. But an acceptable, second-best goal is to make certain the

anti-Israel factions are gone. Israel can't change the reality of Iran’s

existence, but perhaps it thinks it can change the way it interacts with Hamas

and Hezbollah.

For updates click hompage here