By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Rise of the Nonaligned Countries

The global South has

been a net winner from the shifts in global power over the last two decades.

The growing influence of emerging economies, the rise of China as a great

power, tensions between the United States and its European allies, and

increasing great-power competition have given these countries new leverage in

global affairs. They have taken advantage of these shifts by building new

coalitions, such as BRICS (whose first members were Brazil, Russia, India,

China, and South Africa); strengthening regional alliances, such as the African

Union; and pursuing a more assertive agenda at the UN General Assembly. From

championing the Paris agreement on climate change to taking Israel to the

International Court of Justice, the global South—the broad grouping of largely

postcolonial countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East—has

shown a greater willingness to challenge Western dominance and redefine the

rules of the global order.

An “America first”

foreign policy would seem to put those gains at risk. During his presidential

campaign, Donald Trump promised to hit developing countries where it

hurts most: raising tariffs that will throttle exporters in developing

countries; normalizing the mass deportation of migrants, whose remittances are

essential for the economies of many countries in the global South; and

withdrawing from global environmental agreements that provide crucial support

to those people disproportionately affected by the climate crisis. His proposed

economic policies will probably lead to inflation at home, with devastating

knock-on effects for developing countries as interest rates rise globally and

credit becomes more expensive for economies already burdened by debt. His

commitment to targeting China may make it harder for Beijing to continue

serving as an alternative market and source of investment for much of the

world.

But even if Trump

follows through on his promises (and he may not), the bigger story for the

global South should be one of opportunity. Trump has exhibited little interest

in, and often contempt for, the non-Western world, but his return could

paradoxically help countries in the global South advance their own interests.

His hostility to certain international norms will push these countries to work

together more effectively, while his transactional approach will give them the

chance to play the great powers off one another.

And if Trump winds up

accommodating Russia to pry it away from China, that would indicate that

the United States must now navigate a multipolar world—exactly the

understanding of geopolitics that the global South has come to embrace. Indeed,

many governments in the global South welcome his departure from the U.S.

foreign policy tradition of liberal internationalism that purports to make the

world “safe for democracy” but has, since its inception under President Woodrow

Wilson, applied one standard to Europeans and another to everyone else. By

contrast, Trump borrows from another tradition, that of the likes of President

William Taft, whose “dollar diplomacy” used economic influence to extend

American power abroad without moral pretense. Both approaches are forms of

hegemonic reassertion—attempts to cement U.S. primacy on the world stage—but

one cloaks itself in moral superiority, and the other does not. Some developing

countries will feel Trump’s amoral pragmatism as a breath of fresh air and an

opening to promote their interests, whatever the declared aims of Washington.

The Pendulum Swings

The global South is a

capacious category, encompassing a wide variety of countries that have

differing levels of wealth, influence, and aspiration. The interests and needs

of a country with the economic heft of Brazil are very different from those of

a poorer one such as Niger. Not all countries in the global South pull in the

same direction: Indonesia, for instance, increasingly resists taking sides in

the competition between China and the United States, while

Argentina, under its Trump-admiring president, Javier Milei, has reoriented its

foreign policy to hew more closely to American positions. Meanwhile, India is

balancing its traditional solidarity with postcolonial countries against its

desire to become a major military player loosely in the U.S. camp—a shift that

has elevated its global standing as a counterweight to China.

Yet despite its

diversity, the global South has over the decades managed to form effective

coalitions to reshape those international rules long crafted to serve the

interests of the powerful. Its countries have united on occasion to make

international norms more equitable. In the mid-twentieth century, under the

banner of the Non-Aligned Movement, the global South coalition aimed to

dismantle Western imperial legacies—fighting for sovereignty, racial equality,

economic justice, and what it saw as cultural liberation from Western

influence. By the 1970s, the global South had organized under various

groupings, including the G-77 at the UN, to achieve significant victories:

decolonization became enshrined in international law and the principle of

nonintervention in the internal affairs of sovereign states emerged as a global

norm. Organizations such as the oil-trading cartel OPEC used economic leverage

to assert greater non-Western control over natural resources. Crucially, the

advocacy of countries in the global South began influencing rules on nuclear

proliferation, trade, energy, and the environment, codifying in international

law the need for forms of redistributive justice to compensate countries that

had emerged from the ravages of colonialism.

Consider the global

nonproliferation regime: in the 1960s, the United States and the Soviet Union

colluded to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and technological know-how,

aiming to curb proliferation. That rankled many countries in the global South that

sought greater access to peaceful nuclear technology and feared that an

agreement between the superpowers would effectively entrench nuclear weapons,

making it virtually impossible to eliminate them in the future. These countries

banded together and, through years of hard-nosed negotiations, secured a

compromise with the superpowers. The Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, signed in

1968, still favored states that already possessed nuclear weapons, but it

included provisions that encouraged disarmament in powerful countries and

incentives for weaker countries to develop peaceful nuclear energy.

There were reverses,

too. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the United States dismissed the global

South as obsolete, insisting that all countries embrace domestic reforms to

align with a liberal order under American primacy. Structural adjustment programs

from the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank enforced financial

deregulation and austerity, while the United States used the extraterritorial

application of domestic law—notably through the stipulations of Section 301 of

the 1974 Trade Act—to pressure countries to dismantle protective tariffs and

subsidies. Yet globalization unfolded in unexpected ways. It generated new

wealth for many postcolonial countries, propelled China into a position of

rising power, and fueled potent transnational movements such as political

Islam. Although globalization also encouraged a wave of democratization across

the developing world, that outcome did not always benefit the United States and

its Western allies.

U.S. President Bill Clinton reopened

opportunities for the global South. Rhetoric about the so-called liberal

international order appealed to the notion of an interconnected world where

prosperity could be more evenly distributed, including to developing countries.

Clinton was not immune to violating these norms, such as when he bypassed the

UN Security Council to launch NATO’s intervention in Kosovo in 1999. The

Helms-Burton Act in 1996 penalized foreign companies engaged in business with

Cuba, even when such activities were legal in their own countries and lawful in

the eyes of the World Trade Organization.

However, Clinton’s

emphasis on a “rules-based order” allowed countries in the global South to use

international institutions to their advantage. The World Trade Organization

provided a platform for developing countries to negotiate favorable deals,

including the ability to legally challenge stronger economies, helping level

the playing field in international trade. The 1995 World Conference on Women in

Beijing spotlighted gender issues, unleashing an era of progressive change

across the developing world by galvanizing international support for gender

equality initiatives and pressuring governments to better secure women’s

rights. The Kyoto Protocol to the UN Framework

Convention on Climate Change provided a mechanism through which developing

countries could receive financial and technological support for environmental

policies while taking industrialized countries to task for failing to curb

carbon emissions. The World Bank reformed

to prioritize programs that reduced poverty and promoted sustainable

development across the global South. A world of institutionalized global norms,

despite its imperfections, allowed developing countries to hold great powers

accountable and extract meaningful concessions through multilateral mechanisms.

The pendulum swung

after the 9/11 attacks, in whose aftermath U.S. President George W.

Bush insisted, “There are no rules.” This proclamation heralded an era of

unrestrained use of force in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere, resulting in the

direct and indirect deaths of millions of people across the global South. The

United States tortured detainees from developing countries in clandestine

facilities. In many Western countries, Muslims and their religion in general

became the subjects of racialized scrutiny. The humanitarian doctrine of

“responsibility to protect”—that sanctioned intervention to prevent crimes such

as genocide—facilitated invasions and violations of national sovereignty, such

as the NATO-led attack on Libya in 2011, that

seemed motivated more by strategic interests than concerns about the welfare of

people. U.S. President Barack Obama challenged international law by turning

Yemen into a proving ground for drone warfare, causing a fragile state to

spiral into chaos. This interventionism bred instability and triggered mass

migration from Africa and the Middle East to Europe, especially during the

Syrian civil war in the 2010s.

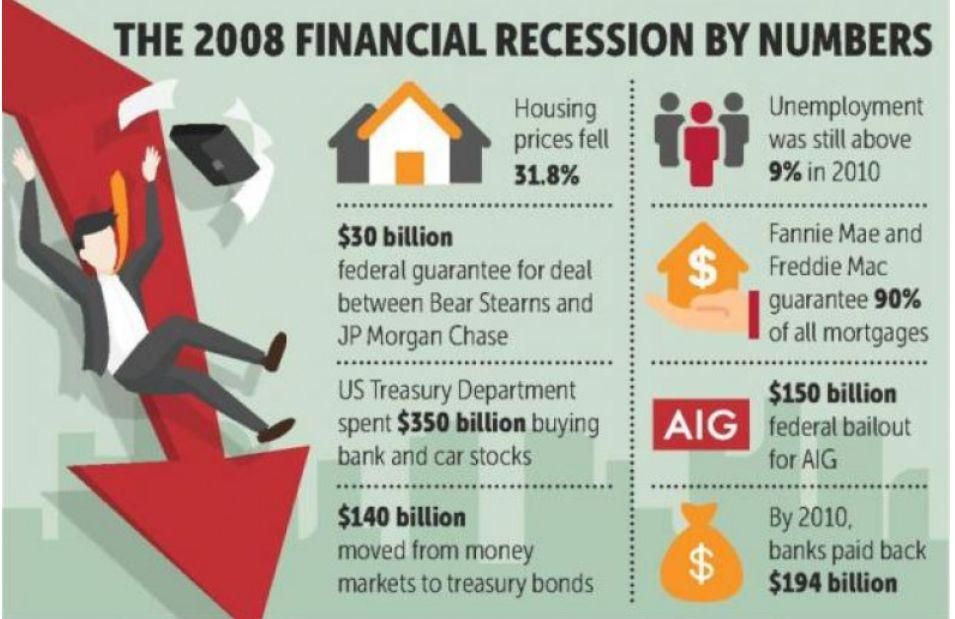

The financial crisis

of 2008 would force the pendulum back in the other direction. It delivered a

devastating blow to the West, exposing the rot within the pillars of the

liberal international order. For the first time in decades, the West needed the

global South. The G-20, which brought

emerging economies such as Brazil, China, India, and South Africa to the table

alongside traditional Western powers, replaced the G-7 as the primary forum for

global economic governance. Non-Western countries won a greater say in crafting

global recovery plans, such as coordinated stimulus measures and reforms to

financial governance. For example, the G-20 oversaw the expansion of

representation in the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank to include

more voices from emerging economies. Concurrently, a range of non-Western

institutions—including the African Union, BRICS, OPEC+ (the expanded version of

the cartel), and the Chinese-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank—became

vibrant arenas of collective action for the global South.

Trump at a G-20 summit in Osaka, Japan, June 2019

Trump’s arrival in

the White House in 2017 slowed the global South’s progress. His sidelining of

the World Health Organization during the COVID-19 pandemic,

withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, and disregard for trade rules by

unilaterally imposing tariffs outside the World Trade Organization framework

had devastating effects. International institutions had offered the global

South some modest protections—without them, weaker states were left vulnerable

to the law of the jungle. In 2020, he announced his administration’s intention

to withdraw from the World Health Organization, for instance, temporarily

freezing U.S. funding for key programs in Africa, undermining efforts to combat

polio and malaria. Trump’s disregard for international institutions also

weakened the extent to which global South countries could influence global

governance. Trump’s demonization of nonwhite migrants from global South

countries further deepened the divide, promoting xenophobia and racist

hostility that has reverberated far beyond U.S. borders.

Not much changed

under U.S. President Joe Biden. His stance on trade largely mirrored

Trump’s. Although Biden initially rolled back some of Trump’s hard-line positions on immigration, he would tack back

toward them in the second half of his presidency. He returned the United States

to the Paris Agreement, but his legislation devised to combat climate

change—including the Inflation Reduction Act—risks becoming a tool for

protectionism, making it harder, not easier, for global South countries to

transition to green economies.

Unsurprisingly, many

developing countries have turned to China in recent years. China’s

transformation from a relatively poor country to a much more powerful and

prosperous one in just a half-century helps it speak to governments and public

in the global South. It has been a major financier for these countries, trading

loans and investments for commodities, raw materials, energy, and port access

to fuel its rapid growth. Beijing capitalized on Washington’s self-inflicted

wounds—such as its calamitous invasion of Iraq in 2003

and Trump’s disdain for international agreements and institutions—to become a

major player in multilateral organizations, in which it often claims to

represent the interests of the developing world.

But there are growing

signs of trouble. As China becomes more powerful, it increasingly treats other

countries not as a partner might, but as a great power would. Many see its

actions as neocolonial, including its imposition of draconian conditions on trade

and investment deals and its heavy-handed diplomacy across Africa, Latin

America, and Southeast Asia. In Southeast Asia, China has shifted from partner

to aspiring hegemon, pressuring countries such as Indonesia, the Philippines,

and Vietnam. Even within BRICS—which is now expanding beyond its founding

members—some worry that China sees the grouping as a vehicle to project

influence rather than a shared platform for collective action benefiting

developing countries. Trump’s return to the White House will not make it any

easier for the global South to balance China with the United States; his trade

protectionism will hurt developing countries across the board.

Delusions of Hegemony

Trump’s campaign

pledges on trade, climate, migration, and taxation are often understood as a

retreat from the world. From the perspective of the global South, however,

these commitments suggest the opposite: they augur an attempt to reassert U.S.

hegemony. When Trump threatens to withdraw from international agreements, he is

actually insisting that the United States can go it alone—and that others

should just fall in line if they know what’s good for them. By sowing

uncertainty about the credibility of American commitments, Trump incentivizes

countries to align more closely with the United States or risk losing out. His

proposed tax cuts and tariffs will fuel inflation, leading to higher U.S.

interest rates. This, in turn, will raise borrowing costs globally, especially

for countries with significant debt, and will drive investors away from

emerging markets toward safer returns in the United States. The resulting

currency depreciation will make imports more expensive, increasing inflation

while reducing productivity in many developing countries. Rather than signaling

isolation, Trump’s campaign pledges are interpreted in the global South as a

calculated strategy of revisionism—a bid to restore U.S. primacy by making

other countries pay heed, align with Washington, or be left vulnerable in an

increasingly uncertain order.

Leaders across the

global South will have little option but to find ways to shield their countries

from the consequences of Trump’s policies. Domestic publics in many developing

countries are far more politically mobilized and technologically empowered than

they were in previous eras, making their demands louder and harder to ignore.

The poor and middle classes in much of the global South benefited significantly

from the economic opportunities that came with globalization and that Trump

threatens. They will expect their leaders to hold the line.

Many governments

will, for instance, continue to explore alternatives to the U.S. currency,

experimenting with nondollar payment systems, digital currencies, and trade

mechanisms in local denominations to blunt the White House’s capacity to coerce

rivals through sanctions and other restrictions. They may seek new, creative

strategies to maintain international trade flows and sidestep the restrictions

imposed by the incoming U.S. administration. Anticipating such moves, Trump

posted to social media in November threatening to impose 100 percent tariffs on

BRICS countries should they pursue an alternative currency “to replace the

mighty U.S. dollar.”

If Trump does indeed

conduct mass deportations, they will hurt his country’s standing in much of the

global South because they vindicate the belief that Trump holds profound

disdain for the non-Western world. This will deepen the divide between the

global North and South on issues of race and cultural difference, straining the

West’s diplomatic relations with countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America

while provoking broader resentment toward Western countries seen as

perpetuating racial hierarchies. Such actions could exacerbate tensions within

the United States, widening the gap between communities over issues of race and

immigration and further undermining the country’s moral authority on the global

stage.

One subject that has

won broad solidarity among the countries of the global South is the Palestinian

cause. South Africa, for example, has taken steps to challenge Israel’s actions

in Gaza at the International Court of Justice, accusing it of committing acts

of genocide. Many governments across the global South view this as emblematic

of broader Western hypocrisy, pointing to how the West largely tolerates the

killing of Palestinian and Lebanese civilians by Israel, even as it

vociferously condemns Russian aggression and the killing of Ukrainian

civilians. This double standard has deepened skepticism in the global South

about the impartiality of the liberal international order. The plight of the

Palestinians will serve as a flash point, a symbol of inequities in the

prevailing international order and, in the eyes of many across the developing

world, the unfinished work of decolonization. The issue will continue to

underscore the persistent tensions between Western and non-Western countries.

Even as Trump gives freer rein to Israeli ambitions, developing countries will

keep using the UN General Assembly and international law to challenge not only

Israel but also the United States.

On climate action,

Trump’s approach promises to embolden interest groups within the global South

that are dedicated to high-carbon industries and the extraction of fossil

fuels. That will shift the domestic balance of power away from proponents of

the green transition. High-carbon interest groups are bound to resist necessary

reforms and make it costlier and slower to effect the green transition

globally. Trump’s relative indifference to climate action could embolden

loggers, ranchers, and miners around the world, leading to further

deforestation and unsustainable agricultural expansions that will exacerbate

climate change, threatening global food security by disrupting ecosystems and

reducing crop yields in both the global South and the

global North.

At the same time,

Trump’s foreign policy could have some curious consequences. Instead of

reasserting American primacy, Washington could come to see that the world has

shifted under its feet. If Trump follows through on his campaign pledge to

lower tensions with Russia while still seeking to pressure China, he may

unintentionally accelerate the drift toward a multipolar world. By easing

hostilities with Russian President Vladimir Putin, Trump would tacitly

acknowledge that Russia cannot be subdued and that Moscow’s quest for regional

hegemony is legitimate—that Russia is entitled to strive to maintain a sphere

of influence. This would vindicate many countries in the global South that have

argued for years that the international system is no longer defined by

unchallenged American hegemony but by a more balanced order, in which the

United States must increasingly eschew the impulsive foreign policy of

unipolarity for calculated restraint. Developing countries will continue

treating both China and Russia as pivotal centers of power, seizing

opportunities to extract economic, security, and technological concessions

through platforms such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a China-led

multilateral group. In a fragmented global order marked by competition and

pragmatic transactionalism, Trump’s policies could

increase the global South’s leverage, enabling it to play great powers off one

another.

To be sure, the

global South lacks the unity and resources to fully blunt the sharper edges of

Trump’s foreign policy. The United States under Trump will still wield

unmatched influence, setting agendas and shaping international rules.

Washington retains the capacity to employ economic coercion, diplomatic

isolation, and even military force to quash serious efforts by developing

countries to challenge U.S. preferences. But the rising agency of the global

South and the expanding geopolitical consciousness among its peoples have

fundamentally altered the dynamics of global power. The U.S. government,

whether under Trump or his successors, will find it increasingly difficult to

ignore the growing political relevance of those countries once consigned to the

margins. Trump’s bid to reassert American hegemony will run into a world that

is far less pliant than he imagines it to be.

For updates click hompage here