By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Myanmar and the looming war for its borderlands Part

one

When I visited Burma, now called Myanmar, in 2015

(shortly after it was a lucky moment because the country had just started to

open up by lifting restringings to go into areas that

two years earlier would still be forbidden to go for someone like me, shortly

before my departure and upon arrival, I posted a sequence of case studies

illustrating what at the time was known about the history of Burman, particularly

also during the colonial period and what happened there during the second world

war, as can be seen here.

It was a lucky time because this was after allegedly

democratic Aung San Suu Kyi (daughter of General Aung San, who fought

with the Japanese against the allied forces during World War II) NLD party

won a sweeping victory in those elections, winning at least 255 seats in the

House of Representatives and 135 seats in the House of Nationalities. In

addition, Aung San Suu Kyi won re-election to the House of Representatives. And

led the leading generals at that time to open up the country, including areas

where foreigners previously were not allowed to go.

This was when Aung San Suu Kyi suddenly became

very much friends with some of the Generals, leading her to minister for the

President's Office, Foreign Affairs, Education, and Electric Power and Energy

in President Htin Kyaw's government. Whereby already that time it became clear

that this only meant a change in the capital Rangoon where people now soon were

able to bu Apple apple

I phones and other goodies with little changes in the countrysides

where I traveled hence on my first day of arrival I quoted what I thought was a

pertinent article stating "It

Is Not Enough for Elites Simply to Get Along" as stated here.

As explained recently,

we know how this ended. Which ten again brings us to the question I started

with when I arrived there in 2015, what next?

The background

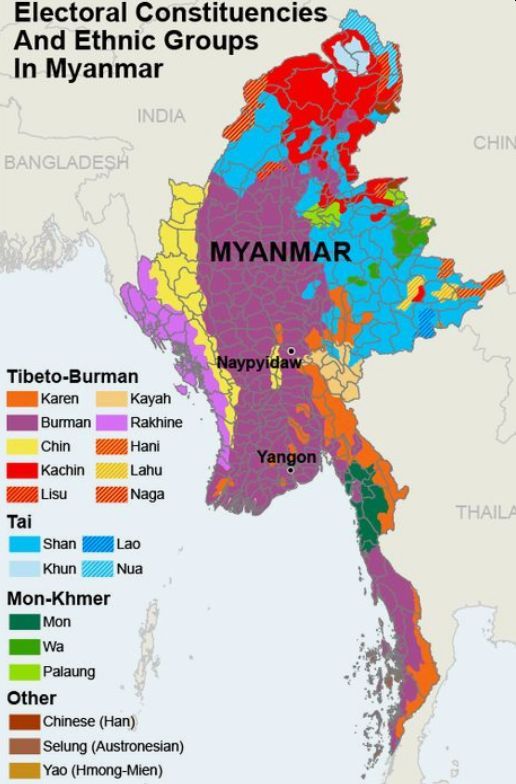

For more than any other country in the world in the case

of Myanmar/Burma, as we also started to do in 2015 with a detailed ten-part historical case study, one

has to look at how the country was created, to begin with, or as we wrote in

2015, before British colonization, Burma or Myanmar, as it is known today,

did not exist. Instead, the region consisted of independent kingdoms; Burman,

Mon, Shan, Rakhine, Manipuri, Thai, Lao, and Khmer kingdoms were located

throughout the area and were engaged in constant conflict.

On 12 February 1947, General Aung San expecting a

handover by the British signed the

Panglong agreement with representatives of the Shan, Chin, and Kachin

people, three of the largest of the many non-Burman ethnic groups that today

make up about two-fifths of Myanmar’s population. The agreement said that an

independent Kachin state was “desirable” and promised “full autonomy in

internal administration” to “Frontier Areas,” as today’s ethnic conditions were

then known. Aung San was

assassinated just over five months later. Under the 60 years of primarily

military rule that followed, the spirit of the Panglong agreement has never

been honored.

As Burma was then called, heading for independence in

the years after World War II, the British colonial power summoned

representatives of its many ethnic minorities for talks at Maymyo,

a picturesque hill station in the highlands east Mandalay called Pyin Oo Lwin.1 The hearings were called the Frontier Areas

Committee of Enquiry, and leaders of the non-Burmese peoples who lived in

territories far away from the country’s heartland on the plains of the

Irrawaddy River were invited to present what they expected from the proposed

Union of Burma. Did they want autonomy for their respective areas? A federation

of equal states? Or even their independent nations, separate from Burma? Under

British rule, central Burma had been ruled as a colony while the more than

forty Shan principalities, or the Federated Shan States, were protectorates.

Other areas were called ‘designated’ or ‘un-administered.’ It was a patchwork

of different jurisdictions, which now had to be brought under some kind of

unified, central administration.

Talks with major non-Burmese ethnic groups—the Shan,

Kachin, Chin, and Karenni (or Kayah)—went smoothly.

They came prepared and asked for autonomy within a proposed federal structure.

The Karen, who had been fiercely loyal to the British colonial power and even

fought with them against the Japanese- allied Burmese during World War II, did

not participate in the talks. Instead, they sent a letter stating that they

wished “to be in a distinct territory under the Governor's direct control,” or

a dominion that would be self-governing but remain under British sovereignty.2

The Wa sent four delegates.

Two of them represented Mong Lun and Hsawnglong, relatively developed Wa

principalities in the southern hills, while the other two came from the wilder

and more remote northern states of Mong Kong and Mong Mon. The hearings were headed by U Nu, who later

became independent Burma’s first prime minister. The southern Wa did not have any specific request. Naw Hkam U from Mong Lun stated only

that “we are not well educated in politics, but we are willing to abide by the

decision of the Federated Shan States Council,”3, while Sao Naw Hseng from Hsawnglong stated that

“Was are Was and Shans, are

Shans. We would not like to go into the Federated

Shan States.”4

If that were not puzzling enough, the talks with the

northern Wa revealed a wide gap between the Wa way of looking at life and the committee's perception of

it: Do you want any association with other people?

Hkun

Sai (for the Wa): We do not want to join anybody

because we have been very independent in the past.

What do you want the future to be in the Wa states?

Sao Maha (for the Wa): We

have not thought about that because we are very wild people. We never thought

of the administrative future. We think only about ourselves.

Don’t you want education, clothing, good food, good

houses, hospitals?

Sao Maha: We are very wild people and don’t appreciate

all these things.

Have you got any ideas as to how you would like the Wa states to be administered in the future?

Sao Maha: No.5

It shows that the Was did not think of themselves as

citizens of Burma, and that was not going to change after independence in 1948

or when the name of the country was altered Myanmar in 1989. The Wa did not have any concept of nations or states and were

never ruled by any outside power. The Frontier Areas Committee of Enquiry s

report stated that there are no post offices, but mails are accepted and

distributed if the administrative officers are addressed. Wa

literacy in any language was minimal, so they would hardly have been avid

letter-writers. The report went on to mention that “the only medical facilities

are those provided by the Frontier Constabulary outpost Medical Officers and by

itinerant Chinese practitioners (non-certificated) ... there is no organized

education service in the Wa states.”7

The early history of these idiosyncratic and isolated

people is shrouded in mystery. They are related to the Palaung, tea growers in

northern Shan State, and the Lawa in the hills of northern Thailand. The Mon

and the Khmer may speak related languages, but only the Wa

have converted to Buddhism. Even the Palaung have converted to Buddhism. Few of

Wa have remained faithful to their animistic beliefs

throughout history, and only in recent years have some become Buddhists or

Christians. We know for sure that the Wa and their

Tawa relatives have inhabited northeastern Shan State, southern Yunnan, and

northern Thailand for centuries. They may even be the original inhabitants of

those areas as the old Lanna kings in north Thailand and the Shan saohpa, or princes, in the eastern state of Kengtung paid a

token yearly tribute to the

When a Kengtung prince was crowned, two Wa always took part in the ceremony, and the Shan chief

would consider his coronation incomplete without them.9 The Wa

may have been despised as ‘savages,’ but the Shan had to recognize their unique

status as genuinely indigenous people. In Lanna, Thai historian Sarassawadee Ongsakul noted “that

the Lua [Lawa] was accepted as the original owners of the land can be seen in

the coronation procession, in which a Lua walks with a dog ahead of the king

into the city,”10 which was present-day Chiang Mai. The Wa

and the Lawa may not have lived in the fertile valleys where the Shan and Thai

settled, but they were undoubtedly the first to form communities in that part

of Southeast Asia.

Chronicles compiled by the Shan rulers, and research

done by British colonial administrators and Chinese officials, provide some

clues, but it is not certain that those accounts are accurate. Based on

interviews and oral history, they also contain widely differing interpretations

of the origin of the Wa. The intrepid British

colonial officer James George Scott, who traveled extensively in upper Burma at

the end of the nineteenth century, claims that the Wa

believe they originated from tadpoles and “spent their earlier years on the

lake at Nawnghkeo, an uninviting-looking oval lake at

the top of a mountain seven thousand feet high ... the lake is about half a

mile long and two hundred yards wide. It is said to be enormously deep, and so

cold that no fish can live in it.”11 When they “became frogs they moved to a

place called Nam Tao where, in the progress of time, they grew to be ogres,”12

and eventually morphed into human beings. According to Scott, they were head

hunters, but not cannibals, as rumored among the Shan who lived nearby and

feared these ferocious tribesmen.

A second version, put forth by V. C. Pitchford in a

1937 essay, also mentioned that lake. The name Nawnghkeo

is Shan for green lake, while the Wa call it Kaing

Kret. But Pitchford’s report has no reference to tadpoles, instead of

recounting that “from its primeval waters sprang the forebears of the Wa race and when they became men, they lived in the cavern

of Pakkatei and there they learned the mystery of

headhunting, whereby they waxed fruitful and multiplied exceedingly.”13 On the

other hand, Willy-Andre Prestre, a French researcher,

was told a story while smoking opium with some tribesmen that they were

descendants of frogs. He also recorded references to some kind of evolution

that eventually resulted in human beings. According to a fourth Chinese

version, “mankind came from a cave called Yang-ho.”14 That version of the

origin of the Wa makes no mention of tadpoles, frogs,

or head-hunting.

All those versions are part of local mythology and, as

Scott once remarked, Wa belief systems are “a jumble

of Buddhism, totemism, and simple fantasy”15 Buddhism entered their belief

systems through contacts with the Shan, called Dai in China, lowlanders living

mainly on the western side of the Wa Hills but also

in the east where they lived together with Han Chinese. The Shan, the British,

and the Chinese divided the Wa into ‘tame’ or ‘big’ Wa, those who had lived close to Shan or Chinese

civilization and adopted some of their respective customs, including Buddhism

and ‘the wild Wa,’ tribesmen who were still animists

with some elements of Buddhism, and also head hunters. It is head-hunting and

the presumed wildness of the Wa that has caught the

imagination of people in the outside world and instilled fear among the

neighbors of these fiercely independent tribesmen.

In his book Burma and Beyond, Scott noted that “the

fact is there has always been a fascination about the Wa.

Europeans first heard of them in the days of Vasco da Gama. At least, there

seems no reason to doubt the assertion about his experiences made in Camoens’ Lusiads that he came

across the Wa among the ‘thousand unknown natives.’

He calls them Gueos and said they were cannibals, and

that certainly was the belief even amongst their nearest neighbors, the Shans and the Burmese, until 1893, when a British party

went across the center of their country,”16 and, presumably, discovered that

they did not eat human flesh but were not averse to the habit of chopping off

people’s heads.

The origin of the Wa

head-hunting tradition is obscure and will probably never be fully fathomed.

One theory was produced by Alan Winnington, the Beijing correspondent for the

British communist paper The Daily Worker, in the 1950s. Armed with his

communist credentials, he was the only Westerner allowed to travel extensively

in remote parts of Yunnan. He later wrote a book called The Slaves of the Cool

Mountains, and although the title refers to the Norsu

tribe in northwestern Yunnan, it also includes a unique account of the Wa. Winnington retells a Wa

legend according to which decapitation began with a trick played on them by

Zhuge Liang, the famous Chinese warrior at the time of the Three Kingdoms, or

AD 220-280. To make them fight each other instead of their Chinese neighbors,

Zhuge has given the Wa boiled rice to plant, which,

naturally, did not grow. He then told the Wa that

their rice would succeed only if they sacrificed human beings and cut off their

heads. After the tribesmen heeded this advice, Zhuge gave them good rice seeds,

which increased.17 Chinese chronicles provide a similar account of the origin

of head-hunting, but there the evil trickster is a Shan, not a Chinese.18

On the Burmese side—and before independence in 1948—colonial

presence in the area was limited to occasional visits by adventurers like Scott

and annual flag marches up to what the British perceived as the border with

China. The Shan writer Sao Saimong Mangrai, a member of the Kengtung princely family, relates

in his book, The Shan States and the British Annexation, that “during the Wa Hills tour of a British officer in 1939, a Sikh doctor

had to be rushed out of the head-hunting area under an escort of a platoon of

troops when it was learned that the Wa had come and

offered 300 silver rupees to some of the camp followers for his head, which,

with its magnificent beard and mustache, they said would bring enduring

prosperity to their village.”19

Saimong Mangrais tale and Western

and Chinese accounts of head-hunting among the Wa

tend to describe it in the context of fertility rites and wishes for good

harvests. Magnus Fiskesjo, a Swedish anthropologist,

disputes this theory and argues that it had more to do with collecting trophies

in war with rival villages. No fertility god or deity figured in the

head-hunting rituals because, as Fiskesjo writes,

“the pantheon of spirits ... had no direct part in the arrangements of enemy

heads and skulls. Wa warfare practices of the past

must be understood within the social and regional context of conflict over land

and resources, not customs.’”20 Whatever the case, warfare between different Wa villages was prevalent. Given the tribal nature of Wa society, it would not have been necessary for someone

like Zhuge or anybody else to play tricks on them with boiled rice to pit one

community against another. As Winnington describes, “the Wa

people live on the jungle hilltops in fortified villages of bamboo, thatched

houses built on stilts.”21 A Wa village called Urnu he saw in China in the mid-1950s was no different from

those across the border in Burma at the same time and earlier:

Like all villages, Urnu is

surrounded by the high growth of dense Thornwood between 15 and 20 yards thick,

with dead and living thorns intertwined to form an impenetrable natural

barbed-wire barrier. At opposite ends of the village, two tunnels are cut

through the fence, closed on the inside by massive doors hacked out of large

trees—hinges, door, and bolt slots all cut from a single piece of

hardwood—giving the village the advantage over attackers in the tunnel.22

Skulls of decapitated enemies were put on display

outside the village to warn off intruders. Each town would have a drum house,

and drums would be heard during a festival or if people from a hostile village

were spotted in the vicinity. The Wa also displayed

heads of buffaloes, complete with impressive horns, as trophies suggesting

wealth and successful hunting trips. The horned buffalo has, in modern times,

become the symbol of the Wa nation.

According to Scott, “Most villages count their heads

by tens or twenties, but in some cases, they run into many more, according to

the age of the village, and whether, as sometimes seems to be the case, the

trophies or, as one might say, the guarantees, of one village, run into and

combine with another.”23 The Chinese, Scott noted, knew the Wa

best “since they have dealings with them in opium and salt.”24 Opium was a

significant cash crop in the hills and, as such, sold to Chinese merchants, and

their contacts spread far and wide in the region. G. F. Hudson, another British

colonial officer who wrote about the Wa during the

early colonial era, G. F. Hudson identifies the Panthay—

Chinese Muslims from Yunnan who had fled into Burma after rising against the

emperor, which lasted from 1855 to 1873 as the primary buyers of Wa opium. Historically, they have been excellent muleteers

and controlled much of the caravan trade in the region, not only the opium

business. In northern Thailand, other goods they transported as far south as

Chiang Mai included salt, tea, minerals, precious stones, and consumer goods.

But opium was a major commodity, and according to Hudson, the Panthay, the opium traders, were “financed by Singaporean

Chinese and they had 130 Mauser rifles with 1,500 mules, exporting opium by the

hundredweight into French, Siamese and British territory, each muleload

escorted by two riflemen.”25 For the little money the Wa

opium farmers got from selling their crop, they could buy salt, rice, and a few

other necessities from the Chinese merchants.

Silver mining was another source of income, and again

the buyers mainly were the Panthay and other Chinese

from Yunnan. Large-scale silver mining was carried out between 1650 and 1800,

and even gave name to what now is a town in the Wa

Hills: Vingngun, Shan for the silver town.’ It is not

unusual that towns and areas in the Wa Hills have

Shan names, and the partial conversion to Buddhism among some of them led to

the adoption of Shan political systems. While some Wa

chieftains did pay tribute to more powerful Shan saohpa,

Fiskesjo also notes that “these Wa

deflected Shan dominance by seizing on their geographical position to set

themselves up as Shan-style princes, on the model of those same threatening

Shan States, to be able to compete with them.”26 The outcome was the emergence

of what became known as the Wa states, sometimes even

spelled with a capital ‘s’.

The best organized of those Wa

states was Mong Lun in the southern hills. Tawang, or Ta Awng as he is sometimes called, proclaimed

himself saohpa in the early nineteenth century. He

died in 1822, and having no sons was succeeded by his nephew Hkun Hseng who had a Shan name,

became a Buddhist, and made the village of Pangkham

the capital of his state. After the British annexation of the Shan States in

the 1880s and 1890s, Mong Lun maintained cordial

relations with the various Shan saohpas and colonial

power. Several of the children in the ruling family were sent to schools in the

Shan States, and it was not unusual that they, apart from their native Wa, could speak Shan, Chinese, Burmese, and even English.27

Thus, it would not be fair to the Wa

to say that they were a backward tribe who lived in total isolation in their

mountains with little or no understanding of the outside world apart from some

interaction with their Shan and Chinese neighbors. The Wa

were more intelligent than that, and even the ‘wild’ ones had a notion of being

a people at the center of the universe. In his Ph.D. thesis, Fiskesjo noted:

The most salient feature of the general situation of

the Wa during the last few centuries is the

persistence of an autonomous Wa center, which was

politically and economically independent. This center was surrounded by a Wa periphery, in which people lived under the tenuous rule

of state societies yet farther beyond. The Wa people

residing in the central Wa lands take it for granted

that they live at the origin of the world they have remained.28

The Wa believe that other

sections of the human race have emerged later out of holes in the Wa mountains “from which all humanity come forth [and they]

have proceeded farther away—because the land was already occupied. This applies

to such non-Wa others as the Shan and the Lahu, the

Chinese and the Burmese, as well as any others still.”29 According to Fiskesjo, “the Wa also see

themselves as living at the top of the world, since it is where the highest and

most imposing mountains are.”30 The Lahu, who speak a Tibeto-Burman language,

are not ethnically or linguistically related to the Wa.

Still, the two hill peoples have always been close and are in some mythology

regarded as brothers.

The special status the Wa

enjoyed among the Shan, and the northern Thai is well documented and may have

enhanced that worldview. Their relations with the Chinese are also

well-established. Modern Chinese sources exaggerate that relationship to fit it

into the notion of a unified nation-state. If official Chinese sources are to

be believed, the Wa “came under the rule of the Han

Dynasty”31 in the second century AD: “After that, through the Tang, Song, Yuan,

Ming, and Qing dynasties, the Va (Wa) people have had

inseparable ties with other peoples in the hinterland.”32 That, of course, is

pure fantasy.

Chinese rule until the fourteenth century and the very

existence of a Wa people was virtually unknown to the

emperors in Beijing until the late eighteenth century.33

Colonial Britain, rather than China, was the first

outside power to claim the Wa Hills. After deposing Thibaw, the last king of Burma, in 1885 and sending him

into exile in India, the British conquered the Shan States. They wanted mainly

to avoid the emergence of an uncontrollable buffer area between them and the

French, who at about the same time were establishing their colonial rule in

Indochina, which included present-day Laos. Sir Charles Crosthwaite, British

Chief Commissioner of Burma in 1887-90, described the situation in this way:

Looking at the country's character lying between the

Salween and the Mekong, it was sure to be the refuge of all the discontent and

outlawry of Burma. Unless a government ruled it not only loyal and friendly to

us but thoroughly solid and efficient, this region would become a base for the

operations of every brigand leader ... or pretender ... where they might muster

their followers and hatch their plots to raid British territory when

opportunity offered. To those responsible for the peace of Burma, such a prospect

was not pleasant.34

Consequently, the Shan States were pacified’ over 1885

to 1890, and those areas achieved a status different from Burma proper. While Thibaw was deposed, the Shan princes were permitted to

retain their titles and rule their respective states like the Indian maharajas.

The Shan States had their administration, police forces, civil servants,

magistrates, and judges as protectorates and not colonies.35

Hudson wrote that “the annexation of Upper Burma in

1885, gave us a frontier with China, much of it so undefined that we had to

arrange for its delimitation by joint commissions of British and Chinese

officers. Neither side wanted the Wa States, a

singularly unattractive area, a liability, not an asset, and the Chinese, when

discussing the map, agreed to leave them on our side of the frontier.”36 The

British, Hudson said, were “left with the burden of policing them and

preventing their annual raids into the civilized territory.”37 Scott had

already concluded that “the Wa never stood against

us, even in their permanently fortified villages. Their shooting was puerile,

and our casualties were a mere handful. Still, their constant sniping and

ambushes were distracting ... [but] since they will never stand, it is

impossible to punish them save by burning their villages.”38

But Hudson also concluded—and that was as late as the

1930s— that “throughout history, the only administered area on either side of

the Burma-China frontier were the valleys and a few main routes. Even for the

Chinese, the hills were No Mans Land, and the Wa

massif was especially terra incognita. Nobody ever went there, and even the

approaches were dreaded, the Salween and Mekong valleys being

malaria-ridden—Chinese officers regarded the whole area as a penal station.”39

The presence of the Wa, and

prevailing myths about them, was another reason why Chinese administrators did

not venture into these remote mountains. Dorothy J. Solinger wrote in her study

of ethnic minorities in Yunnan:

The wild Kawa [i.e., Wa],

living between the Salween and the Mekong Rivers, were head-hunters. Their

fondness for warfare, and their superstitious belief that Chinese heads were

the most efficacious for their sacrifices, had historically kept the Han out of

their hills quite effectively ... these Kawa hated the Han and never came under

their influence. Only a few scattered Shan settlements dotted the otherwise

homogenous, isolated, and mountainous wild Kawa homeland on the Burma border.40

There is no historical evidence to suggest that the Wa saw Chinese heads as especially preferable or that heads

were used in religious rites. Still, just the notion that it could be true was

enough to keep all Chinese except some brave and locally connected silver and

opium traders out of the Wa Hills. Interaction with

the Shan was mainly in the valleys, and then when Wa

came down from their hills to buy or barter specific necessities.

Britain, however, had a fundamental strategic interest

in controlling the Chinese frontier. That meant establishing a semblance of

stability along the border and leaving the Wa to run

their affairs as long as they did not raid the lowlands. There was also nothing

there of any commercial interest. By the end of the nineteenth century, the

silver deposits had been depleted, and the opium grown in the Wa Hills was of poor quality, and most of it was consumed

locally.

The British policy towards the Wa

was to contain them rather than try to administer their hills. Peace in the

frontier areas was important because Britain’s interest in Burma was a backdoor

to China for trade and commerce. Other colonial powers recognized the strategic

importance of Burma, and some of them had been in the region even before the

British arrived on the scene. One of the first was the Vereenigde

Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC), or the Dutch East

India Company. Having lost Formosa, or Taiwan, to rebellious Chinese forces

from the mainland in 1662 and then been excluded from Chinese ports, the Dutch

sought alternative trade routes to China. Burma seemed an obvious way from the

Bay of Bengal to the vast Chinese market, and that was why the Dutch maintained

a significant presence in Burma for nearly half a century. Their eye was on the

northern Irrawaddy River port of Bhamo at the beginning of an old trade route

called the ambassadors’ road,’ which ended in Yunnanfu,

today’s Kunming. Bhamo, in today’s Kachin State, was as far north as the

influence of the Burmese kings stretched in those days.

The VOC failed. “Time and again,” Dutch historian Wil

O. Dijk wrote, “the Company’s factors in Burma pleaded with the King to allow

the VOC a trading post on the Sino- Burmese border, but to no avail.

Eventually, this ban became a major factor contributing to the Dutch decision

to abandon Burma.”41 That was a significant setback for the Dutch because, as

Dijk writes, “there is perhaps no route by which overland traffic between

southwestern China and any point on the Bay of Bengal can so readily be carried.”42

Nevertheless, Dutch merchants stayed in Burma even

after the British conquest in the nineteenth century, and the colony attracted

a wide range of other merchants from all over the world. Rangoon, the capital

of British Burma since 1853, became one of the most cosmopolitan cities in

Asia, with significant foreign communities of Indians, Chinese, Armenians,

Jews, Persians, Europeans, and Eurasians. It was, of course, not because of

trade with China, but all kinds of commercial activities benefited from Burma’s

strategic location at the crossroads of South and Southeast Asia.

Some modern Chinese writers are eager to find

historical justifications for President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative

(BRI). Pan Qi, a former vice-minister of communications, wrote for the

September 2, 1985 issue of the official Chinese weekly Beijing Review that

there was a road connecting western Yunnan with southeast and west Asia.43

There is no doubt that Zhang Qian wrote extensively about trade routes to and

from China, Central Asia, and beyond.44 But his attempts to forge a way from

Sichuan to India proved unsuccessful.

There may never have been a ‘southern Silk Road,’ but

the ‘ambassador’s road,’ sometimes called the ‘tribute road,’ was real,

although it could hardly be described as a highway. It got its name because

some Burmese kings and Shan princes paid tribute to the Chinese emperor, which

is interpreted as a kind of recognition of Chinese sovereignty over those

regions. This tribute payment should be seen as a bribe, not acceptance of the

authority of a higher power. Several Shan princes paid tribute to the Burmese kings

for precisely this reason.

British rule in Burma—and the Shan States—was meant to

change all that. On March 1, 1894, China and the United Kingdom signed a

convention meant to regulate, and perhaps even stimulate, cross-border trade.

There was even talk about building a railway from Burma to China. From 1894 to

1900, Major Davis, a British official, made remarkable surveying the northern

Shan States and Yunnan for possible railway routes. He found that the most

convenient way would be from Mandalay over the hills to Lashio and Kunlong on the Salween River. Along the Nam Ting River, a

Salween tributary, the terrain was relatively flat into Yunnan, where mountains

once again dominated the landscape.45 Davis argued that the railway should be

built on commercial—to facilitate cross-border trade—and political grounds: to

control the backdoor to China to secure British influence over Yunnan and other

restive provinces.

Unfortunately for Davis, his final surveys of the

projected railway across Yunnan were lost when his colleague, Captain W. A.

Watt-Jones was killed during the Boxer Rebellion in Beijing in 1900. If the

plan had materialized, the railway would have skirted the northernmost fringes

of the Wa Hills. The cost of such a railway would

also have been prohibitive. Davis estimated that a meter-gauge line would cost

20 million pounds and that the construction would take at least ten years.46 A

railway was built from Mandalay to Lashio, including the spectacular Gokteik Viaduct, built-in 1899 and opened in 1900.

Components for the 689-meter-long bridge were made by the Pennsylvania Steel

Company and shipped to Burma. The height of the bridge is 102 meters, the

highest in Burma and, at the time, the largest railway trestle in the world.

But after that, nothing more happened on the railway

front. Overall, trans-Burma trade with China proved disappointing, and Burma

Railways abandoned all construction plans beyond Lashio to the Chinese

frontier. John LeRoy Christian, a US army major, wrote in 1940 that even jade

from the mines around Hpakan

in Kachin State was no longer sent along the ancient routes through Guangxi

in southern China, but went by sea from Rangoon to Guangzhou and “Britain and

France forgot Yunnan and their rivalry for its trade.”47

It was not until 1937 that China and Britain awakened to

the importance of the Yunnan gateway. China was at war with Japan, Shanghai was

attacked, and the Japanese navy blockade Chinas maritime ports. Work then began

building an all-’weather highway from Burma to Yunnan to supply the Chinese

forces resisting the Japanese advance in the east. It was not only a matter of

cutting a road over the mountains of Yunnan. The Salween and the Mekong, two

great rivers, are also spanned by modern steel-cable suspension bridges.

Anywhere from 150,000 to 300,000 men using the most primitive engineering

equipment went to work, and as soon as it was opened in 1939, hundreds of

trucks sped off on the 1,145-kilometer run from Lashio to Kunming. Even after

its completion, no fewer than 30,000 men were kept constantly at work on

maintenance and improvement of the surface to make sure it could carry heavy

traffic.48 That was, of course, the famous and fabled Burma Road that wound its

way in numerous switchback curves over the mountains.

Then, the Japanese invaded Burma in January 1942. The

Burma Road was cut, and the allied forces—the United Kingdom and the United

States—had to look for an alternative route to send supplies to the Kuomintang

forces in China's interior. The American commander, General Joseph W. Stilwell,

who earned the nickname ‘Vinegar Joe’ for his short temper and abrasive manner,

came up with a bold solution: to cut an entirely new road from the small town

of Ledo in Assam in northeastern India across northernmost Burma into China,

where it would link up with the older Burma Road. He argued that it would be

possible because the Japanese never fully conquered the Naga and Kachin hills

in the north. Local Kachin guerrillas, supported by the United Kingdom and the

United States, were constantly harassing the Japanese. With some more Allied

support, they should maintain reasonable safety for the road construction

crews. Stilwell, who had served as a military adviser to the nationalist

Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek, did not want to abandon him and his forces in

their fight against the Japanese. He had also brought Chinese soldiers to

India, where they were trained and equipped to assist the Allied forces. For

the British, it was also the beginning of the campaign to re-establish their

rule over Burma.

First went Stilwells

American-trained Chinese divisions, driving the Japanese before them. On either

side, Chinese and American patrols provided security for the road construction

teams in flanking movements. The trailblazers came to the heels of the Chinese

divisions, marking out the line with axes for the armored bulldozers that

followed. Last came the primary labor force, who blasted the road, paved it,

and constructed steel bridges across the innumerable streams and rivers along

the way.

While the Burma Road was built by Chinese labor,

Stilwell's road construction effort was one of the most mixed anywhere in the

world. Lieut.-Col. Frank Owen, a British officer in one of the teams, described

the laborers: “Chinese, Chins, Kachins, Indians, Nagas, Garos slashed, hauled

and piled, Negroes drove machines. Black, brown, yellow, and white men toiled

shoulder-deep in the streams, belt-deep in red mud. On one camp, 2,000 laborers

spoke 200 different dialects.”49

It was the British Empire that struck back against the

Japanese. Soon weapons carriers, tanks, and infantry columns flowed down the

ten-meter-wide double-tracked, metaled, trenched, banked, and bridged road

which Stilwell had initiated. The road, known as ‘the Stilwell Road’ or ‘the

Ledo Road,’ became a new highway stretching from Ledo to Kunming, totaling

1,726 kilometers.

Other dry-weather roads were built by Allied engineers

and local labor from India into the Chin Hills, from Manipur to the Chindwin

River, and the Arakan region across the border from East Bengal. The Japanese

were forced out of Rangoon in May 1945, and on August 15, their last units

surrendered to the Allied forces at the southeastern city of Moulmein. As LeRoy

Christian remarked in 1945, “Altogether, the isolation of Burma had been

destroyed by the current war.”50

The same was also held in the Wa

Hills. But their contacts with the outside world had already entered a new

stage when the first Western missionaries arrived there in the 1930s. The

trailblazer was Marcus Vincent-Young, an American Baptist whose father William

Young had come to Burma in 1892 and began spreading the gospel in Kengtung in

1901. After failing to convert any Buddhist Shan, he turned to missionary work

among the Lahu in Kengtung city's hills. The Lahu, like some other Southeast

Asian peoples such as the Karen further to the south in Burma, held a legend

predicting that a white man holding a big book would one day arrive to bring

salvation among people who could not read and write.

Adoniram and Ann Judson, American Baptist

missionaries, became aware of that tale when they arrived in southeastern Burma

in 1813, and to their initial astonishment, Karen came down in the thousands

from their hills to welcome the white foreigners.51

Similarly, thousands of Lahu flocked to Kengtung to

see and listen to Young, a white American who wore a white tropical suit and,

like the Judsons, carried his Bible wherever he went. He capitalized on the

fact that the Lahu had a similar belief, and his conversion rate was so high

that a delegation was sent to Kengtung to investigate. According to US

researcher Alfred McCoy:

Although the investigators concluded that Reverend

Young was pandering to pagan myths, Baptist congregations in the United States

were impressed by his statistical success. They had already started sending

significant contributions to ‘gather in the harvest.’ Bowing to financial

imperatives, the Burma Baptist Mission left the White God free to wander the

hills.52

Young put the Lahu language into Roman script and his

son Vincent, who went to work mainly among the ‘tame Wa

in the 1920s, did the same wherever he went. In 1933, Vincent Young and his Wa colleagues romanized the Wa language and published the first book in this new

script, a collection of hymns, identified on its title page as being written in

the ‘Kaishin dialect.’53 A complete translation of

the Bible into romanized Wa

was published in 1939. Vincent Young also founded a church and a missionary

school in Menglian in the Wa

area of southern Yunnan. The school educated hundreds of Wa

and Lahu students, many of whom became pastors of Christian congregations in Menglian itself and Gengma, Cangyuan, Shuangjiang, and

Lancang, all counties now on the Chinese side of the Sino-Burmese border.54

A constant problem for the British nominal overlords

was to determine the exact location of that border, which led to confrontations

with the Chinese when they, in the nineteenth century, began to claim the

mountains on the southern fringes of Yunnan. The British had made some attempts

to penetrate the area already before World War II. A Commission was

appointed to more firmly demarcate the border between Burma and China, and in

193536, attempts were made for the first time to survey the Wa Hills. The British also stationed two officers in the Wa Hills to “introduce light administration.”55

The road that was built into the northern Wa Hills in 1941 was part of those efforts. However, large

tracts of the Wa Hills remained inaccessible. It was

simply too dangerous for any outsider to venture into the areas where

head-hunting was still rife. Finally, in 1941, the British and the Chinese

agreed on where the border should be. But then the war broke out, and the

British were forced to leave Burma. Rangoon fell to the Japanese on March 8,

1942, and the rest of the colony was soon overrun as well. In the far north,

the Japanese did not establish control and in some parts of the Shan States.

The Burma Independence Army (BIA), led by Burmese

nationalist hero Aung San, had assisted the Japanese when they marched across

the border from Thailand and occupied Burma. But wary of local, ethnic

sentiments—many of the non-Burmese nationalities tended to be anti-Burmese as

well—the Japanese kept the BIA out of the Shan States when they tried to enter

the area in 1942.56 It was not until September 22, 1943, that Japan decided to

transfer “the Karenni states, Wa

states, and the whole of the Shan states except for Kengtung and Mong Pan state”57 to a Burmese puppet regime which the

Japanese had established in Rangoon on May 8 of that year. That regime

continued to govern Burma until the end of the war and was dissolved only when

the British returned. It was the Imperial Japanese Army that remained the most

powerful institution in Burma throughout the occupation.

Kengtung and Mong Pan were

given to Thailand, a Japanese ally, whose support was necessary to secure the

borders of the occupied territories. As the British had evacuated Burma and the

Shan States in 1942, they sought help from Chiang Kai-shek, who sent the 93rd

Division into Kengtung while the 249th and 55th Divisions moved into the Karenni States and the southern Shan States. According to

Shan historian Sai Aung Tun, “the Chinese soldiers were generally not well

trained or well-equipped like the Japanese. The Chinese were badly defeated by

superior numbers and mechanized equipment, including airplanes, against which

they had no defense.”58

On May 3, 1942, twenty-seven Thai airplanes flew over Kengtung,

where the Chinese troops were stationed, and bombed the market. The bombardment

inflicted heavy casualties on the Chinese, who withdrew close to the Chinese

border to the north. A few weeks later, Thai troops led by Field Marshal Pin Choonhavan and his son, Chatichai

Choonhavan, marched into Kengtung, and the Thai flag

flew over the town.59 Kengtung, with 31,000 square kilometers, the biggest of

the Shan States, and the much smaller Mong Pan State

across Thailand’s northwestern border, were placed under Thai administration,

which the Japanese recognized the following year. Thailand was also given areas

in northern Malaya and western Laos as part of the Japanese scheme to establish

what they called ‘The Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere.’60

Fierce fighting raged for months in the north. As the

British and their mostly Indian troops retreated towards India or China, they

were bombed by the Japanese. According to Sai Aung

Tun, “corpse after corpse lay scattered in towns,

especially Lashio, Hsenwi,”61 and along the Burma Road, “which came to be known

as the Road of Death.”62 The Wa Hills, however, was

never the scene of any severe warfare. The Japanese were probably as afraid as

anybody else to enter the area. The only recorded exception occurred in the

northern Wa Hills shortly after the Japanese

invasion. A small contingent of Japanese troops, escorted by a Shan from west

of the Salween River, attacked a Wa settlement near Mong Mau and killed twenty-one villagers who, presumably,

were armed as well.63

The situation was different in Kokang immediately to

the north of the Wa Hills. There, the local Chinese

population resisted the Japanese when they tried to enter the area at Kunlong on the Salween River. The local ruler of Kokang,

Yang Wen-pin, allied himself with the nationalist Chinese, and in 1943 he and

his then twenty-three-year-old son Yang Kyein-sein,

or Jimmy Yang, were invited to visit Chiang Kai-shek at his wartime capital of

Chongqing.64 Jimmy Yang later became a prominent businessman and politician in

Burma, and in the 1960s and 1970s, joined a rebel army opposed to military

rule.

Kengtung and Mong Pan were

returned to the Shan States when the British returned in 1945, not to

reestablish colonial rule but to prepare for Burma’s independence. The Frontier

Areas Committee of Enquiry was an important part. The Karen never joined the

talks and did not, in 1947, go to the small market town of Panglong, north of

the Shan States capital Taunggyi, to sign an agreement which paved the way for

Burma to become a democratic federal republic with local autonomy for the

frontier areas. The day representatives of the Shan, the Kachin, and the Chin

signed the Panglong Agreement with Aung San. February 12 is still celebrated as

Union Day, a national holiday.65

The Shan saohpa also asked

for and were granted the right to secede from the proposed Union of Burma after

ten years of independence, that is, in 1958, should they be dissatisfied with

the new federation. This right was ensured under the first Burmese

Constitution, Chapter X, but applied only to the Shan and Karenni

states. The 1947 Constitution stipulated that other states could also be

formed, the first would be for the Kachin and the Karen, but those states would

not have the right to secede from the Union.66

Talks with the Wa did not

produce any tangible results or recommendations. Based on the Panglong

Agreement and the 1947 Constitution, Burma became an independent federal

republic on January 4, 1948, but it had no absolute jurisdiction of the Wa Hills. During the last years of colonial rule, the

British had attempted to establish some indirect control by appointing Harold

Young, William Young's son and Vincent’s brother, as assistant superintendent

of Mong Lun and adjacent areas. Although he was

American, he had been given the rank of captain in the British Army. He was

commanded by two mostly Shan soldiers who fought against the Japanese when they

occupied most of Burma. Harold Young’s knowledge of the area and local

languages were invaluable assets to the British. He also saw action with the

Americans and the British against the Japanese in the Kachin Hills in the

country's far north. He was recruited by the US Office of Strategic Services, a

forerunner to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).67

After the war, Harold Young tried and convicted

several local warlords suspected of having collaborated with the Japanese. Khun

Ja, the uncle of Khun Sa, became a prominent drug trafficker in the 1960s and

ran his private army in the Golden Triangle. Thailand, Burma, and Laos meet in

this notorious drug-producing area until he eventually surrendered to the

Burmese government in January 1996. A gunshot executed Khun Ja to his head on

the banks of the Irrawaddy River.68

Whatever control the British, and after 1948 the

government of independent Burma may have had in some outlying areas, was

abandoned when in the early 1950s renegade nationalist Chinese Kuomintang force

overran large tracts of the eastern Shan States. Beaten and defeated by Mao

Zedong's communists in the Chinese civil war, they had been unable to join the

main force that retreated, along with Chiang Kai-shek, to Taiwan. The only

alternative to surrender was to regroup in the mountains across Chinas southwestern

border.

However, Kuomintang soldiers first entered the

northern Wa Hills and then marched through Mong Lun, where the local ruler protected his people and

their area. The nationalist Chinese pushed on to the mountains north of

Kengtung, the home of Akha, Palaung, and other hill peoples. That area was

easier to control than the wild Wa Hills. The

Kuomintang also established Kokang, a district north of the Wa

Hills populated by ethnic Chinese of Yunnanese stock.

Even if the Kuomintang presence in the Wa Hills was

relatively limited, the Wa, who had been largely

spared the devastation of World War II, found themselves caught up in the

intricacies of world politics.

The Kuomintang built an airbase at Mong

Hsat near the Thai border. Soon, supply flights began

to arrive from Bangkok and Taiwan, where the Republic of China, defeated by the

communists on the mainland, lived on under Chiang Kai-shek and his main

Kuomintang force. The effort was supported by the United States and its Central

Intelligence Agency (CIA), and the plan was to reconquer the mainland from

those bases in the northeastern mountains of the Shan States. It was, in a

sense, the CIA’s first secret war, and General Li Mi, the Kuomintang officer in

charge of the operation, was proclaimed commander of the ‘Yunnan Province

Anti-Communist National Salvation Army’69.

The United States and its allies were fighting under

the United Nations banner against North Korean and Chinese forces on the Korean

peninsula. Claire Chennault, a hardline former US general and World War II

hero who had served as an adviser to Chiang Kai-shek, later admitted publicly

that a plan existed to wage a broader war against China, using Burma as a

springboard:

It is reported—and I have reason to believe it is

true—that the Nationalist [KMT] Government offered three entire divisions ...

of troops to fight in Korea. Still, the great opportunity was not putting the

Nationalists in Korea. It was a double envelopment operation. With the United

Nations forces in Korea and the Nationalist Chinese in southern areas ... the

Communists would be caught in a giant pincer ... this was a great

opportunity—not to put the Nationalist Chinese in Korea, but to let them fight

in the south.70

Between 1950 and 1952, the Kuomintang army in Burma’s

Shan States tried to invade Yunnan but was repeatedly driven back across the

border. The Burmese Army then entered the Shan States to rid the country of its

uninvited guests, which led to an unprecedented militarization of the Shan

States. But the areas east of the Salween River were too remote to be affected

by the buildup. There, the Kuomintang reigned supreme through alliances with

local warlords, most of them from Kokang and the eastern Shan States, but some

were also Wa.

The Burmese government raised the issue in the United

Nations. On April 23, 1953, the General Assembly adopted a resolution stating

that “these foreign forces [i.e., the Kuomintang] must be disarmed and either

agree to internment or leave the Union of Burma forthwith.”71 At first, the UN

resolution seemed to have had some impact on the situation. On October 29, a

joint US-Thai-Taiwan communique was issued in Bangkok, stating that 2,000

nationalist soldiers, including their families, would be withdrawn. Taiwan also

pledged it would no longer supply the troops in Burma with weapons, and those

who remained there would be disowned.72

The evacuation began in February 1954 and lasted for a

month. Kuomintang soldiers were brought by truck from the border to Chiang Mai

in northern Thailand. They were paraded through the streets in bright uniforms

and newly issued tennis shoes before boarding US aircraft destined for Taiwan.

Other units left via Chiang Rai north of Chiang Mai and Lampang to the south.

The evacuation no doubt weakened the Kuomintang, but

several thousand of its troops remained in the hills of the eastern and

southern Shan States. It was also becoming increasingly clear that not all the

troops sent to Taiwan were genuine Kuomintang soldiers. The US researcher

Alfred McCoy noted:

“Many of the troops carried rusting museum pieces as

their arms. Now allowed into the staging area, the Burmese observers frequently

protested that many supposed Chinese looked

more like Lahus or Shans. Although other observers ridiculed those

accusations, the Burmese were correct. Among them, there were a large number of

boys, Shans, and Lahu. Even by 1971, there were an

estimated 300 Lahu tribesmen still living in Taiwan who had been evacuated

during this period.73

The Yunnan Province Anti-Communist National Salvation

Army was officially disbanded, but thousands of nationalist Chinese soldiers

remained in the Shan States and settlements with Thailand. The hill peoples

living in the areas where they operated were the most tragic victims of the

war, which continued for years after the so-called repatriation in 1954. Elaine

Lewis, an American Baptist missionary working first in Kengtung and then in

northern Thailand, wrote in 1957 that “at the time the Chinese Communists

occupied Yunnan Province to the border of Kengtung State in 1950, a great flood

of hill peoples came down to Kengtung State.”74 According to Lewis, the

Kuomintang invasion forced many of them to flee again:

For many years there have been large numbers of

Chinese Nationalist troops in the area demanding food and money from the

people. The areas in which these troops operate are getting poorer and poorer,

and some villagers are finding it necessary to flee ... many hill people from

the region have found their way into the hills of northern Thailand so that no

one may discover substantial numbers of Lahus, Akhas,

Meau [Hmongj, Was, and other hill tribes originally

from Kengtung in the hills of northern Thailand.75

Even if some villagers fled across the border when

soldiers from the Chinese Peoples Liberation Army

(PLA) entered southern Yunnan in the early 1950s, they were at first quite

lenient in their treatment of the hill peoples. Hardly any Chinese had been

there before, which was the reason some fled. The PLA was seen as a foreign

force, so people were afraid and did not expect. But the main reason the PLA

had entered the area was to prevent the Kuomintang from crossing the border

with Burma, and for that, they needed the support of the local people. In his

account of his travels in the Chinese Wa Hills,

Winnington met a Wa leader called Jabuei,

who told him that the PLA first came into the area in 1950 and called him and

other village headmen to a meeting:

They said they were against the Kuomintang, so we

listened to them, although they were Hans [Chinese]; they told us that there

would be no more oppression of the minority peoples once the Kuomintang was

driven out the Hans. We should be masters of our own lives, and they would

co-operate with the headmen and bring a better life to all the Wa people. Instead of stealing from our people, they would

get gifts and new doctrines that would help the Wa to

grow rich like the Hans.76

To spread literacy among the Wa

in China, the new communist authorities introduced an unknown writing system

for their language in 1957. Like the Wa script

invented by Vincent Young and his Wa workers, it was

also based on the roman alphabet but was designed to be closer to the then-new

pinyin romanization of Chinese characters.77

Chinas own way of romanizing

the Wa language was, as Fiskesjo

points out, part of a broader scheme “to support the political and military

consolidation of Chinese rule over the area, and the introduction of social and

economic reforms.”78 Primarily, it included the establishment of Chinese rule

where there had been none before, including crushing

what the Chinese communists labeled canfei, ‘bandit

remnants,’ or the remnants of the Kuomintang.79

After a few years of leniency, the Chinese authorities

introduced an entirely new oppressive system as soon as the Kuomintang threat

had been eliminated. Weapons in possession of Wa

tribe members, who were used to being armed because they depended on hunting,

were confiscated, and according to Fiskesjo all

paraphernalia associated with head-hunting was thoroughly destroyed, along with

the social institutions that sustained independent Wa

society:

Drum-houses were torn down, along with any njouh head-poles [a head-hunter’s head-container] planted

near them; the log drums were thrown out or burned. The roadside a nog [head-container posts planted along with the approach

to a village] were destroyed or abandoned. The significant rituals of the past

were abandoned. Chief ritualists and other leaders were demoted, marginalized,

or even persecuted.

Wa

elders Fiskesjo spoke to regarded 1958 as the

critical watershed “since in that year the Chinese shifted policy from

reconciliation to enforcement.”81 Even the Wa had to

become Chinese communists and were herded into people’s communes.

In the Shan States of Burma, discontent was simmering.

As Shan’s constitutional right to secede from the Union was coming into force

in 1958, meetings were held in many towns, and demands were raised for

independence. The Burmese Army’s war against the Kuomintang meant that the Shan

had become squeezed between two forces, both of which were perceived as foreign

and oppressive. The government tried to suppress the growing nationalist

movement by using the army and its dreaded intelligence service, which, in effect,

functioned as a secret police force. But the outcome was counterproductive.

Groups of young people moved into the jungle, where they organized armed

guerrilla units. One such group was Noom Suk Harn, or

‘The Young and Brave Warriors,’ led by Saw Yan Da. His other name was Sao Noi,

and he was a Shan from Yunnan. He was joined by some university students who

had fled the towns when the Burmese Army began its campaign to suppress the

Shan nationalist movement.

In 1959, a well-known Union Military Police officer

named Bo Mong joined the rebellion. He was an ethnic Wa, and with a band of Wa

warriors and Shan students, he launched a surprise attack on the garrison town

of Tang-yan. They managed to capture Tang-yan while another group tried, unsuccessfully, to attack

Lashio in the north. It was not a well-planned and synchronized military

campaign, and the Burmese Army eventually managed to recapture Tang-yan. But the authorities in Rangoon were taken aback by the

sudden outburst of violence in the Shan States. Tang-yan's

battle marked the beginning of a long war between the Union Government and

various Shan rebel armies.

In 1959, the Shan saohpa-whose

attitude to the rebellion had been ambivalent—some supported it while others

wanted to remain within the Union—formally renounced all their powers at a

grand ceremony held at the state capital of Taunggyi and attended by all the saohpa as well as the commander of the Burmese Army,

General Ne Win, who was then heading a caretaker government. The duties of the saohpa were taken over by the elected Shan State

government. The Shan States became Shan State, and it was hoped this would

satisfy the aspirations of the nationalists. It did not. In April i960, a new,

better-organized rebel force, the Shan State Independence Army, was formed by

Shan students who, dissatisfied with the authoritarian rule of Sao Noi, had

broken away from his Noom Suk Harn.82

In the early 1960s, the Kachin in the far north were

also getting prepared to rebel. General Ne Win had allowed elections in 1960,

and U Nu was returned to power. But one of his election promises had been to

make Buddhism the state religion of Burma, a move seen by the predominantly

Christian Kachin as an open provocation.

In i960, the Burmese and Chinese governments had

finally managed to demarcate their shared border. As part of the deal, three

Kachin villages and the Panhung-Panglao area in the Wa Hills had been handed over to the Chinese in exchange

for Burmese sovereignty over an area northwest of the town of Namkham known as the Namwan

Assigned Tract. The village tracts in Kachin State encompassed 152 square

kilometers, and the Wa territory ceded to China was

189 square kilometers in area.83 The deal was not unfair by international

standards, but rumors soon spread across Kachin State to the effect that vast

tracts of Kachin territory had been handed over to China.

On February 5, 1961, in response to making Buddhism

the state religion and the border issue, a group of Kachin led by World War II

veteran Zau Seng formed the Kachin Independence Army (KIA). It soon took over

large tracts of land in Kachin State and the Kachin-inhabited areas of northern

Shan State.

On the Thai border, Karen, Karenni,

and Mon rebel armies had been active for years. Burma was in turmoil, and on

March 2, 1962, General Ne Win stepped in, overthrew the elected government of U

Nu, and introduced not a caretaker government, as in the late 1950s, but a

straightforward military dictatorship. While it was meant to contain and

eventually crush the ethnic insurgencies, the outcome was just the opposite.

Those rebellions flared anew as opposition grew against the new military

government, which had abolished the limited autonomy the ethnic areas had

enjoyed under the 1947 Constitution and replaced it with the strict centralized

rule. The 1962 coup also led to the rebirth of the insurgent Communist Party of

Burma, which from powerful beginnings in the early 1950s had dwindled into a

rag-tag army holding out in isolated pockets in central Burma.

1. Minutes from the

hearings were published as Frontier Areas Committee of Enquiry 1947: Part II

(1947). Rangoon: Government Printing. See also Tualchin

Neihsial (ed.) (1998), Burma: Frontier Areas

Committee of Enquiry Report. New Delhi: Inter- India Publications (first

printed in the United Kingdom in 1947 by His Majesty's Stationery Office.) I

have used ‘Burma as the name for the country. In 1989, the then ruling military

junta decided to call it ‘Myanmar5 even in English texts (it has always been

Myanmar or Bama in the Burmese language, the former being a more formal name

and the latter used in colloquial speech). At the same time, the names of many

local places were changed as well, among them Maymyo,

which became Pyin Oo Lwin.

2. Frontier Areas

Committee of Enquiry 1947 p. 175*

3. Ibid. p. 35.

4. Ibid. p. 36.

5. Ibid. pp. 37, 39.

6. Ibid. p. 190.

7. Ibid.

8. For an account of

the relationship between the Lawa (or Lua) and the Shan and the northern Thai,

see Sarassawadee Ongsakul,

History of Larina (2005). Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, pp. 30-32.

9. G. R Hudson, The Wa People of the Burma-China Border (1957), St. Anthony's

Papers, 11, Far Eastern Affairs. London: Chatto & Windus, p. 128.

10. Sarassawadee

(2005), p. 32.

11. Sir J. George Scott (1932), Burma and Beyond.

London: Grayson & Grayson, p. 292.

12. Ibid. p. 292.

13. Quoted in Taryo Obayashi (1966), ‘Authropogonic

Myths of the Wa in Northern Indo-China. 5 Hitotsubashi Journal of Social Studies, vol. 3, no. 1, p.

45. Available at

https://hermes-ir.libhit-u.ac.jp/rs/bitstream/10086/8490/24/HJs0c0030100430.pdf

14. Ibid. p. 46.

15. Quoted in ibid. p. 59.

16. Scott (1932), p. 292.

17. Alan Winnington (1959),

The Slaves of the Cool Mountains: The Ancient Social Conditions and Changes Now

in Progress on the Remote South-Western Borders of China. London: Lawrence

& Wishart, p. 131. Zhuge Liang is spelled Chu Ko-liang in Winningtons book.

18. Ma Jianxiong

(1913), ‘Clustered Communities and Transportation Routes: The Wa Lands Neighboring the Lahu and the Dai on the Frontier.5

Journal of Burma Studies, vol 17, no. 1, p. 107. Available at

http://www.ha.cuhk.edu.hk/Papers%202013/Ma%20

Jianxiong_Clustered%2oCommunities%2oand.pdf

19. Sao Saimong Mangrai (1965), The Shan

States and the British Annexation. Ithaca: Cornell University Southeast Asia

Program, p. 271.

20. Magnus Fiskesjo (2014), ‘Wa Grotesque:

Headhunting Theme Parks and the Chinese Nostalgia for Primitive

Contemporaries,5 Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology, vol. 80 (August), p. 3.

Available at https://www.tandf0nline.c0m/d0i/abs/10.1080/00141844. 2014.939100

21. Winnington

(1959), p. 131.

22. Ibid. p. 133.

23. Scott (1932), pp. 296-97.

24. Ibid. p. 299.

25. Hudson (1957), p.

129.

26. Magnus Fiskesjo (2010a), ‘Mining, History, and the Anti-state Wa: The Politics of Autonomy between Burma and China,5

Journal of Global History, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 248.

27. Saimong (1965), pp.

263-64, and Sao Sanda Simms (2017), ‘Great Lords of the Sky: Burma’s Shan

Aristocracy.5 Self-published under Asian Highlands Perspectives, no. 48, pp.

415-16.

28. Magnus Fiskesjo

(2000), The Fate of Sacrifice and the Making of Wa

History. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Chicago, p. 49.

29. Ibid.

30. Ibid. p. 50.

31. Ma Yin (ed.)

(1989), Chinas Minority Nationalities. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, p.

278.

32. Ibid. pp. 278-79.

33. Magnus Fiskesjo (2012), ‘Kinesiska perspektiv pa Wa-folkets

historia5 (in Swedish), Kina Rapport (March 13), p. 80.

34. Sir Charles

Crosthwaite (1912). The Pacification of Burma. London: Edward Arnold, p. 128.

Available online at https://archive.org/stream/pacificationofbuoocrosrich/

pacificationofbuoocrosrich_djvu.txt

35. For a succinct

history of Shan-Burmese relations during the British era, see Chao Tzang Yawnghwe [1987] (2010), The

Shan of Burma: Memoirs of a Shan Exile. Second, revised edition, Singapore:

Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, pp. 47-90.

36. Hudson (1957)*

PP* 129-30.

37. bid. p. 130.

38. G. E. Harvey (1933), 1932 Wa

Precis: A Precis Made in the Burma Secretariat of all Traceable Records

Relating to the Wa States. Rangoon: Office of

Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery, Burma, p. 40.

39. Hudson (1957), p.

129.

40. Dorothy J. Solinger (1977), ‘Minority

Nationalities in Chinas Yunnan Province: Assimilation, Power, and Policy in a

Socialist State’ World Politics, vol. 30, no. 1 (October), p. 12. Available at

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259380631_

Minority_Nationalities_in_Chinars_Yunnan_Province_Assimilation_Power_and_

Policy_in_a_Socialist_State

41. Wil O. Dijk (2006), Seventeenth-century Burma

and the Dutch East India Company; 1634-1680. Singapore: Singapore University

Press, p. 191.

42. Ibid. p. 175.

43. Ibid.

44. See Tian Jinchen,

‘One Belt and One Road: Connecting China and the World5 (2017), paper prepared

for McKinsey and Company (April 19). Available at https://

www.mckinsey.com/industries/capital-projects-and-infrastructure/our-insights/

one-belt-and-one-road-connecting-china-and-the-world

(accessed March 20,2018) Tian mentions how Zhang Qian ‘helped establish the

Silk Road,5 but there is nothing about his attempts to reach India.

45. For the plans to

build a railway to China, see John L. Christian (1940), ‘Trans-Burma Trade

Routes to China,5 Pacific Affairs, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 185-87. Available at

https:// www.jstor.org/stable/275i052?seq=i#page_scan__tab_contents

46. Ibid. p. 186.

47. Ibid. p. 187.

48. Ibid. p. 188. See

also H. G. Deignan (1934), Burma: Gateway to China. Washington: The Smithsonian

Institution, p. 15.

49. Frank Owen

(1984), The Campaign in Burma. Dehra Dun:

Natraj Publishers, p. 76.

50. John LeRoy Christian (1945), Burma and the

Japanese Invader. Bombay: Thacker & Company, p. 360.

51. See San C. Po (1928), Burma and the Karens.

London: Elliot Stock, p. 23. See also Bertil Lintner [1994] (2011), Burma in

Revolt: Opium and Insurgency Since 1948. Fourth edition, Chiang Mai: Silkworm

Books, pp. 49-51.

52. Alfred W. McCoy

(1972). The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia. New York: Harper Torchbooks, p. 304.

53. ‘The Young

Family’s Work with the Wa People5 Available at

http://www.humancomp. org/wadict/young_family.html

54. Ibid.

55. Hudson (1957), p.

133.

56. Samara Yawnghwe (2013), Maintaining the Union of Burma 1946-1962:

The Role of the Ethnic Nationalities in a Shan Perspective. Bangkok: Institute

of Southeast Asian Studies, Chulalongkorn University, p. 120.

57. Sai Aung Tun

(2009), History of the Shan State: From Its Origins to 1962. Chiang Mai:

Silkworm Books, p. 203.

58. Ibid. p. 195.

59. Chatichai Choonhavan later became

a Thai politician and served as the country's prime minister from 1988 to 1991.

60. Sai Aung Tun (2009), pp. 201-2.

61. Ibid. p. 200.

62. Ibid.

63. This according

to Singapore scholar Andrew Ong.

64. Yang Li, The

House of Yang: Guardians of an Unknown Frontier, Sydney: Bookpress,

1997, p. 51.

65. For the full text

of the Panglong Agreement, see http://www.ibiblio.org/obl/docs/

panglong_agreement.htm and for download, http;//www.myanmar-law-library.

org/law-library/laws-and-regulations/constitutions/the-panglong-agreement-1947.html

66. The full text of

the 1947 Constitution is available at http://www.myanmar-law-

library.org/law-library/laws-and-regulations/constitutions/1947-constitution.html

(accessed March 20, 2019). Chapter IXU78 states that “The Provisions of Chapter

X of this Constitution shall not apply to the Kachin State.” Chapter IX:i8i

(10) says that “The Provisions of Chapter X of this Constitution shall not

apply to the Karen State.”

67. David Lawitts (2015), £The Grand Old Man of Chiang Mai: The Life

of Harold Young.1 Chiang Mai City Life (April 1). Available at

https://www.chiangmaicitylife.

com/citylife-articles/the-grand-old-man-of-chiang-mai-the-life-of-Harold-young/

68. Ibid.

69. Lintner [1994]

(2011), p. 127.

70. US Congress,

House. Committee on Un-American Activities (1958), International Communism

(Communist Encroachment in the Far East): 'Consultations with Maj.- Gen. Claire

Lee Chennault, United States Army.’ 85th Congress, 2nd Session, April 23, pp.

9-10.

71. Kuomintang

Aggression Against Burma (1953). Rangoon: Ministry of Information, p. 95.

72. Robert Taylor (1973),

Foreign and Domestic Consequences of the Kuomintang Intervention in Burma.

Ithaca: Cornell University Southeast Asia Program, Data Paper no. 93, p. 49

73. McCoy (1972), p.

133

74. Elaine T. Lewis

(1957), 'The Hill Peoples of Kengtung State,' Practical Anthropology, Vol. 4,

no; 5, p. 224.

75. Ibid. pp. 224,

226.

76. Winnington

(1959), p. 129.

77. Justin Watkins

and Richard Kunst (2006), ‘Writing of the Wa

Language’ The Wa Dictionary Project. London: School

of Oriental and African Studies (July 30). Available at

http://www.humancomp.org/wadict/wa_orthography.html

78. Fiskesjo (2000), p. 35.

79. Ibid.

80. Fiskesjo (2014), p. 8.

81. Ibid.

82. For this period

in Shan rebel history, see Lintner [1994] (2011), pp. 195-97, and Chao Tzang Yawnghwe [1987] (2010), pp.

109-11.

83. For a map of the

border and the areas ceded to China, see Josef Silverstein (1977), Burma:

Military Ride and the Politics of Stagnation. Ithaca: Cornell University Press,

p. 174. For an account of the early years of the Kachin rebellion, see Lintner,

[1994] (2011), pp. 199-101.

For updates click homepage here