By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

It Took Just Seven Words But NBA-China's

Viewership Is Approaching Pre-Ban Levels.

It took just seven words

for the National Basketball Association to get canceled by Beijing. As

pro-democracy protesters swarmed the streets of Hong Kong in October 2019,

Daryl Morey, then the general manager of the Houston Rockets, one of the NBA’s

30 teams, posted a simple message to his Twitter account: “Fight for freedom,

stand with Hong Kong.” Chinese broadcasters and streamers quickly announced

that they would no longer show his team’s games. The league, which has more

viewers in China than in the United States, immediately tried to distance

itself from Morey’s tweet, writing that the general manager didn’t speak for

the NBA and issuing a statement that implicitly rebuked him. That response

fostered a backlash among fans outside China and did nothing to please Beijing.

A bipartisan collection of U.S. senators blasted the league for not standing by

Morey’s freedom of expression while all 11 of the NBA’s Chinese sponsors and

partners suspended their cooperation. With a couple of exceptions, China’s

broadcasters stopped airing NBA games until March 2022. The league’s

commissioner, Adam Silver, estimated that the rupture cost his organization

hundreds of millions.

At first glance, the

row between China and the NBA may seem like small potatoes: a tiny example of

how the U.S.-Chinese relationship is now more defined by contestation than by

close economic partnership. But Beijing’s behavior toward the NBA is emblematic

of a much more significant and worrying pattern that the Biden administration’s

China strategy does not wholly address. Over the last dozen years, Beijing has

slapped discriminatory sanctions on trading partners interacting with Taiwan or

supporting democracy in Hong Kong. It has imposed embargoes on and fueled

boycotts against countries and companies that speak out against genocide in

Xinjiang or repression in Tibet. Indeed, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has gone

after almost any entity that has crossed China in any way. And this strategy

has worked. Because the Chinese economy is so integral to global markets,

China’s coercive behavior has caused tens of billions of dollars in damage. The

mere threat of Chinese cutoffs is now prompting states and businesses to stay

quiet about Beijing’s abuses.

This silence is both

deafening and dangerous. The CCP is carrying out a genocide of China’s Uyghur

minority in Xinjiang, engaging in a wide variety of other human rights abuses,

and menacing nearby countries—but states are too afraid to respond. Left

unchecked, this paralysis could hollow out the postwar liberal order. Should

they fear significant penalties? Few governments, for instance, will come to

Taiwan’s defense if China attacks it. They will not help New Delhi if China

attempts to take more Indian land in the Himalayas. They will hesitate to join

the White House’s supply chain initiatives.

Concerned countries

could appeal to the World Trade Organization, the usual arbiter of

international economic disputes, to try to free them from the specter of

Chinese sanctions. But the WTO is unlikely to be of any help. It can

investigate an 80.5 percent Chinese tariff on Australian barley as

discriminatory. Still, if China stops importing bananas from the Philippines or

stops sending tour groups to Korea by citing the “will of the Chinese people,”

there is little the organization can do in response.

The Biden

administration is aware that Chinese economic predation is a significant

problem. It has responded by advocating resilient supply chains among

like-minded partners in everything from personal protective equipment to memory

chips, allowing these states to stop relying so much on Chinese-made goods. The

administration has also imposed export controls on the transfer of advanced

computing chips and chip-making equipment to China. It may soon extend these

controls to quantum information science, biotechnology, artificial

intelligence, and advanced algorithms.

But these efforts are,

at best, a partial solution. Countries may be able to wean themselves from some

Chinese goods in the supply chain, but Biden cannot reasonably expect most of

them to decouple from one of the largest economies in the world. Export

controls by the United States on transferring cutting-edge technologies to

China won’t work unless other countries possessing such technology—including

Denmark, Japan, the Netherlands, South Korea, and the United Kingdom—join in.

And these states may choose not to participate in Washington’s supply-chain and

technological coalitions because they fear Chinese economic retaliation.

To successfully

compete with China,, the United States needs to do more than insulate

states from Chinese coercion. It needs to stop the pressure from happening in

the first place. To do so, the United States will need to band together with

its partners and draw up a new strategy, one of collective resilience. China

assumes it can boss other countries around because of its size and central role

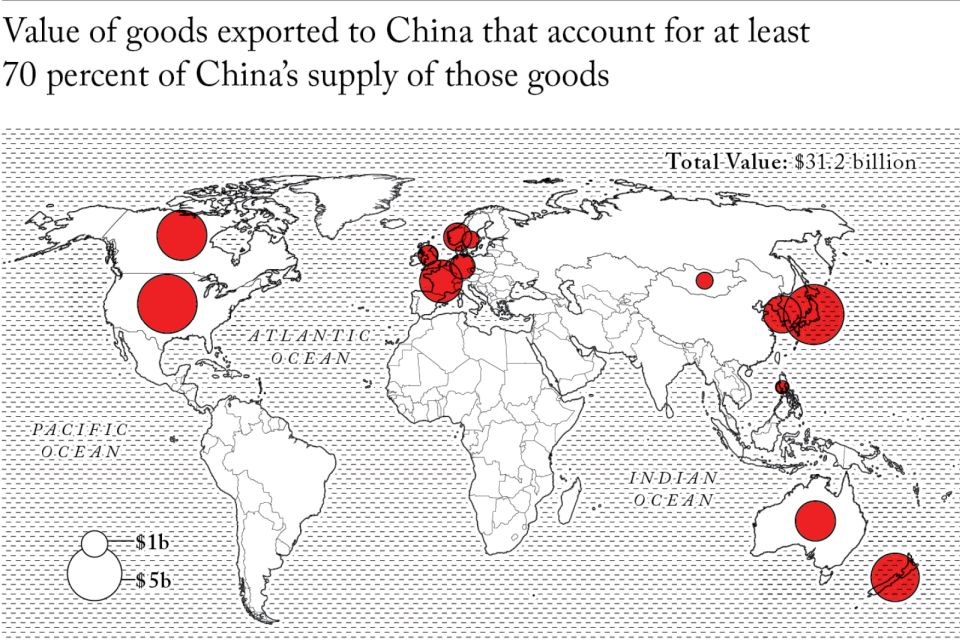

in the global economy. But China still imports enormous numbers of goods: for

hundreds of products, the country’s economy is more than 70 percent dependent

on imports from states that Beijing has coerced. Together, these goods are

worth more than $31.2 billion to the Chinese economy. For nearly $9.1 billion

worth of items, China is more than 90 percent dependent on suppliers in states

it has targeted. Washington should organize these countries into a club that

threatens to cut off China’s access to vital goods whenever Beijing acts

against any single member. States will finally be able to deter China’s

predatory behavior through such an entity.

Dealing with China’s

weaponization of trade will be necessary if the Biden administration wants to

compete successfully with Beijing. And although a U.S.-led collective

resilience bloc may strike proponents of globalization as mercantilists, they

should understand that it is essential to their project. China will continue to

abuse its economic position and distort markets until it is forced to stop.

Collective deterrence may be the best way to keep the global economy free and

open.

Wild Abandon

China’s predatory

actions are carefully designed to hit countries where it hurts most. Consider

what Beijing did to Norway in 2010. After a Norwegian committee awarded the

Nobel Peace Prize to a Chinese dissident, Beijing heavily restricted imports of

Norwegian salmon. Over the next year, the product went from cornering almost 94

percent of China’s salmon market to just 37 percent, a collapse that deprived

the Norwegian economy of $60 million in one year. After South

Korea agreed to host a U.S. missile system in 2016, Beijing forced stores

in China owned by the enormous Seoul-based Lotte Group to shut down, causing

over $750 million in economic damage. China similarly banned and then heavily

restricted the sale of group tours to South Korea, costing the country an

estimated $15.6 billion.

Beijing also

frequently targets individual businesses if they or their employees deviate

from China’s official positions. In 2012, Chinese protesters—encouraged,

according to a Los Angeles Times report, by Beijing—shut down

Toyota’s manufacturing plants in China in response to tensions over the Senkaku

Islands, which are administered by Tokyo but which Beijing claims (and refers

to as the Diaoyu Islands). In 2018, Beijing took the website of Marriott Hotels

offline for a week after the company sent an email to its rewards members. It

listed Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, and Tibet as separate countries. The company

apologized and issued a public statement against separatist movements in China.

The same year, Beijing made more than 40 airlines—including American, Delta,

and United—remove references to Taiwan as a separate country on their websites

simply by sending them a threatening letter. And in 2021, the Chinese state

media egged on a boycott of the Swedish fashion retailer H&M after it

expressed concern about forced labor in Xinjiang. H&M sales in China quickly

dropped by 23 percent.

To be fair, China is

not the only country that engages in economic coercion. It is, in some ways,

endemic to the international system. Writing on these pages in January

2020, political scientists Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman observed

that globalization had enabled many countries to leverage financial power

in pursuit of political ends, a phenomenon they have called “weaponized

interdependence” in their earlier work. This isn’t always a negative. Indeed,

in some situations, states have weaponized interdependence to target bad

international behavior. For example, the widespread Western sanctioning of

Russia for the war in Ukraine and the United States' financial sanctions

against North Korea and Iran for nuclear proliferation were designed to curtail

illegal and dangerous acts.

But what China is

doing is different, both in scale and kind. The United States may

issue frequent sanctions, but these follow a clear set of processes: Washington

does not weaponize economic interdependence through such a wide variety of

means. One recent study identified 123 cases of coercion since 2010, carried

out through widespread boycotts against companies, restrictions on trade,

limits on tourism to foreign countries, and other mechanisms. And aside from

when the Trump administration levied a bizarre spate of tariffs against

American allies, no other government has imposed sanctions or embargoes so

casually, penalizing states for mild annoyances rather than broadly

unacceptable international actions, such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. There

is, for example, a direct correlation between countries whose leaders have met

with the Dalai Lama and a decline in those states’ exports to China.

Beijing is

unapologetic about using these sanctions and does not acknowledge that they

violate global trading norms. It is not worried about domestic discontent

arising from its behavior because the illiberal nature of China’s political

system insulates the government from pushback. And because its trading partners

are all more dependent on China than the other way around, Beijing usually has

the advantage. As the Chinese ambassador to New Zealand warned in 2022, “An

economic relationship in which China buys nearly a third of the country’s

exports shouldn’t be taken for granted.”

Half Measures

Beijing’s long-term

objective is to force governments and companies to anticipate, respect, and

defer to Chinese interests in all future actions. It seems to be working. Major

democracies such as South Korea remained silent when China passed a national

security law in Hong Kong suppressing democracy in 2020. In 2021, Brazil did

not exclude the Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei from its 5G auction for

fear of losing billions of dollars in business. In 2019, after the Gap clothing

company released a T-shirt design with a map of China that did not include

Taiwan and Tibet, it issued a public apology. It removed the shirt from the

sale even before Beijing said anything. After the salmon restrictions in 2010,

Norwegian leaders refused to meet with the Dalai Lama when he visited in 2014.

And according to reports and investigations by various organizations, including The

Atlantic, The Wall Street Journal, and the human rights

nonprofit PEN America, Hollywood companies won’t produce films that cast China

in a negative light for fear of losing ticket sales.

Beijing’s apparent

success doesn’t mean that countries have sat idly by while China has weaponized

economic interdependence. The world’s heavy reliance on Chinese

manufacturing—starkly illustrated by shortages of masks and other personal

protective equipment in the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic—has

prompted almost every country to become more attuned to its economic security.

Japan, for instance, set up a new cabinet position for financial security in

October 2021 and passed legislation to guard critical supply chains and

technologies. During the spring of 2022, in the aftermath of Beijing’s coercion

and the pandemic, South Korea created an early warning system designed to

detect threats to nearly 4,000 key industry materials. The South Korean

government also established a new economic security position in the

presidential office.

Fans watching an NBA game in Shenzhen, China, October

2019

States have also gotten

better at redirecting trade, meaning that when China imposes tariffs or an

import embargo on a target state’s goods, the target state finds alternative

markets. This strategy has seen some success. Throughout 2020, China approved

tariffs on Australian barley, coal, and wine in response to Canberra’s calls

for an independent investigation into COVID-19’s origins, prompting Australia

to redirect these goods to the rest of the world. When China restricted exports

of rare-earth minerals to Japan over a territorial dispute in 2010, Japan

diversified its sources of critical minerals and invested more in domestic

seabed exploration. As a result, it has reduced its dependence on China for

necessary minerals from 90 percent to 58 percent in a decade.

Countries are now

following Biden’s advice to “reshore” and “friend

shore” supply chains, moving vital elements of the production from China (or

places where China exercises inordinate influence) to manufacturers back home

or to trusted partner economies. Through the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue,

known as the Quad, Australia, India, Japan, and the United States are

building resilient supply chains for COVID-19 vaccines, semiconductors, and

emerging and critical technologies, including those related to clean energy.

The countries participating in the Biden administration’s Indo-Pacific Economic

Framework are working on establishing an early warning system, mapping out

critical supply chains, and diversifying their sources for imported goods. In

June, the United States announced the Minerals Security Partnership, an

alliance with Australia, Canada, Finland, France, Japan, Norway, South Korea,

Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the European Union to safeguard the supply of

copper, lithium, cobalt, nickel, and rare-earth minerals. Japan, South Korea,

Taiwan, and the United States are contemplating the creation of an alliance

called Chip 4 that would consolidate the semiconductor supply chain.

These measures are

all valuable and necessary. But they need to constitute a comprehensive

solution. Reshoring and friend shoring insulate states against China’s

disruptions to the production chain while doing nothing to stop its economic

coercion: securing the supply of one product does not prevent Beijing from

cutting countries off from another product. Indeed, countries’ enthusiasm for

participating in such measures is limited by fears that China will retaliate.

South Korea, for example, has hesitated to join the Chip 4 alliance partly

because it is concerned that Beijing would once again ban many of its consumer

goods and block the flow of Chinese tourists. Supply chain resilience, trade

diversion, and reshoring can work only if complemented by a strategy crafted to

end China’s predatory economic behavior.

Flipping The Script

Part of China’s

hubris in practicing economic coercion against its trade partners comes from

the confidence that the targets will not dare counter-sanctions with concrete

action. Beijing is suitable to be confident: it is hard for any country to go

up against an economic behemoth. China, for instance, accounts for 31.4 percent

of global trade in Australia, 22.9 percent in Japan, 23.9 percent in South

Korea, and 14.8 percent in the United States—. In contrast, those countries

account for 3.6 percent, 6.1 percent, 6.0 percent, and 12.5 percent of China’s

trade.

But these states can

fight back if they work together or, in other words, practice collective

resilience. That strategy would flip the script. Australia, Japan, South Korea,

and the United States may individually be at a disadvantage but combined, they

account for nearly 30 percent of China’s imports, exceeding what China’s

exports account for in most of theirs. Add Canada, the Czech Republic, France,

Germany, Lithuania, Mongolia, New Zealand, Norway, Palau, the Philippines,

Sweden, and the United Kingdom—all countries Beijing has coerced in the

past—and the collective share of China’s imports is 39 percent. These states

all produce critical goods on which China is especially dependent. China gets

nearly 60 percent of its iron ore from Australia, which is essential to its steel

production. It gets more than 80 percent of its bulldozers and Kentucky

bluegrass seed, significant for sowing fields, from the United States. More

than 90 percent of China’s supplies of other goods—cardboard, ballpoint pens,

cultured pearls—are sourced from Japan. And 80 percent of China’s whiskey comes

from the United Kingdom

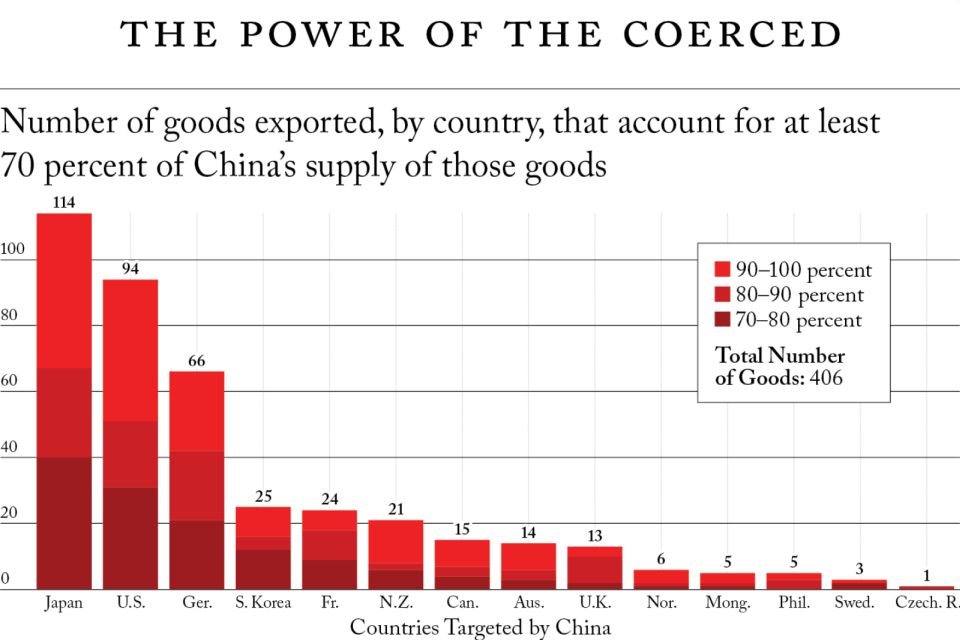

Source: United Nations COMTRADE database

To build a bloc that

can stop Chinese coercion, Australia, Japan, South Korea, and the United States

must first agree among themselves. The first three governments are the United

States’ key allies in the Pacific, and all four nations are major market

democracies and the core stakeholders in the region’s liberal political and

economic order. A commitment to join forces would not be without risk, but all

have been prime targets of Chinese financial predation and have a powerful

incentive to collaborate.

These four states

must then take stock of which other countries are willing and able to join in,

working through existing partnerships such as the Indo-Pacific Economic

Framework to promote the strategy. The 12 other states most profoundly affected

by Chinese economic coercion would be the best membership candidates. Many of

these countries may be very weak compared with China. But if they joined forces

with the four main members, they would enjoy formidable leverage: for 406 items,

China imports more than 70 percent of what it uses from one of these 16 states;

for 171 of those items, the import figure rises to 90 percent. (Lithuania and

Palau do not produce any of these goods, but both are frontline states in need

of protection, so they should be welcomed into the coalition.) The four

founding countries could also approach the European Union, which is currently considering milder measures to

counter Beijing’s coercion, to see whether it is interested in joining their

effort.

The impact of these

imports is far from trivial. For example, China relies on Japan for more than

70 percent of its supplies of 114 items, amounting to over $6.2 billion in

trade, and more than 90 percent of its reserves of 47 items, worth over $1.7

billion. China is over 70 percent dependent on U.S. producers for 94 items,

totaling over $6.0 billion, and 43 items for which China is around 90 percent

dependent on U.S. producers, worth over $1.5 billion. All 406 of the “high

dependence” goods produced by coerced states are worth more than $31.2 billion

to China.

Strength In Numbers

But having the

capability to fight back is only half the battle. The other half is political

will: For collective resilience to be credible, countries must be willing to

sign up for it in the face of fierce Chinese resistance. Beijing is likely to

use a combination of carrots, such as discounted digital infrastructure, and

sticks, such as more export restrictions, to deter countries from joining and

try to peel them off if they do. States will need to build enough domestic

political support to withstand the external pressure and resist the temptation

to free-ride by accepting coalition support without ever actually sanctioning

China.

Given that most

participants would be democracies, this will prove difficult. But the pact’s

more prominent countries can take several steps to help smaller or poorer

states endure the discomfort. They can create a collective compensation fund

for losses and offer alternative export or import markets to divert trade in

response to Chinese sanctions. Bigger states can also provide clear

reassurances to smaller powers that they would not be left high and dry if

Beijing slapped them with sanctions. That means the larger countries, mainly

the original four, would need to delineate clear actions they would take to

restrict important exports to China if Beijing bullied any pact member, even if

those steps were economically costly to them. The four organizing members would

also have to agree on what types of bullying would elicit a response. Disputes

over trade that could be adjudicated by the WTO, such as whether China can

adjudicate Western technology patent protections in its courts, would not meet

the threshold. The trigger would be coercive Chinese economic actions taken for

political purposes.

Yet despite the

challenges, states would likely recognize that joining the pact and staying the

course is worth the short-term costs. They would need to recognize and explain

to their citizens that ending Chinese economic coercion would ultimately be in

their long-term interests. China could initially fight against the new group by

finding alternative suppliers for one, two, or several high-dependence goods.

But suppose tariffs, nontariff barriers, or embargoes were applied to a wide

range of the 406 high-dependence items made by prospective coalition members.

In that case, the costs of finding new suppliers might cause Beijing to think

twice before taking coercive actions. Eventually, China would have to stop such

behavior, resulting in a level playing field for all of the collective’s

participants.

The participating

states could feel confident that China would indeed stop. Despite its

authoritarian system, China has proved quite sensitive to supply chain

obstacles, evidenced by the fact that it rarely applies sanctions to imports of

high-dependence goods. Beijing was happy to cut off South Korea from Chinese

tourists, but it has not sanctioned Samsung; it needs the company’s memory

chips. It has not touched Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, another

critical supplier of computer chips, even as tensions with Taipei reach new

heights. In all its sanctioning of Australia, Beijing never threatened

Australian iron ore, even though it is one of the country’s most lucrative

exports.

Suppose Beijing is

unwilling to locate alternative sources for Australian iron ore at dependency

levels of 60 percent. In that case, it will undoubtedly be sensitive to the

many goods for which it is more than 70 percent dependent on outside

countries—not to mention the ones where its dependence exceeds 90 percent. Then

there are the 40 products made in the United States and Japan, on which China

is 99 or 100 percent reliant. Beijing does not want to lose access to any of

them, especially when it is already struggling from a general economic

slowdown.

Fair And Square

The idea of

collective resilience may trouble proponents of free trade and globalization.

But collective resilience is not a trade war strategy but a peer competition

strategy. It is defensive, resting first on the threat to weaponize trade, not

on the actual use of sanctions. If China does not use its economic power to

coerce, there is no need to make good the threat.

The strategy is also

clearly and narrowly targeted. Its participants are not trying to punish China

just for the sake of doing so; the goal is not to undermine the nation’s

economy. The goal is to deter acts of economic coercion that do not conform to

WTO rules and are aimed at meeting Chinese political goals unrelated to trade.

According to an analysis published by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, a

nonprofit think tank, about a proposed European Union instrument to combat

Chinese coercion, collective resilience could even comply with WTO regulations.

China’s acts of economic hostility are beyond the remit of the organization’s

laws, and nothing in the WTO rulebook prohibits states from engaging in

self-defense.

That’s not to say that

practicing economic resilience will never require sanctions on China. It may

well do so, at least at first. But policymakers can rest easy knowing that any

sanctions, if properly structured, would ultimately be in service of protecting

economic interdependence. That notion may seem paradoxical, but sometimes

conducting international relations requires living with contradictions. It

certainly wouldn’t be the first time the United States has played dirty to keep

a global system clean. During the Cold War, Washington routinely countenanced illiberal

practices to protect the liberal order—for example, supporting anti-communist

military regimes in South Korea and Taiwan as bulwarks against more brutal

nearby powers. Today, the West may need to compromise on its free trade

principles to prevent Beijing from corrupting globalization. It may need to be

aggressive. A successful defense, after all, requires a good offense—including

in great-power competition.

For updates click hompage here