By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Trump’s Threat to U.S. Intelligence

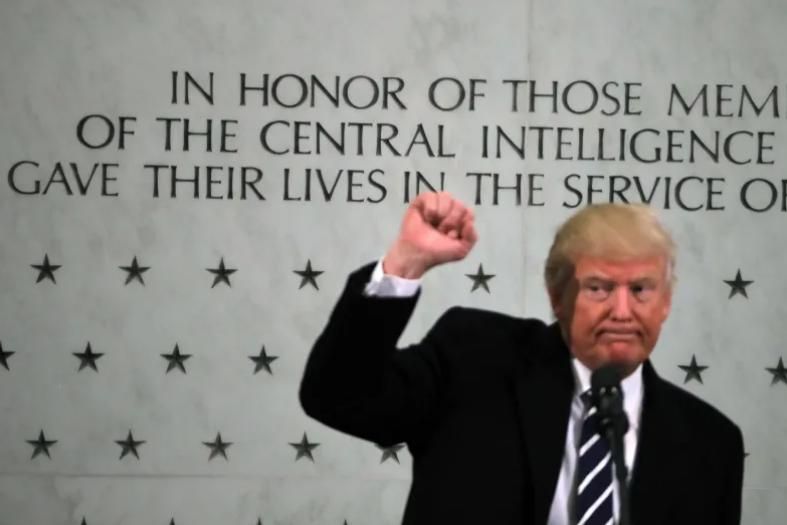

On January 21, 2017, the

day after his inauguration, U.S. President Donald Trump visited Central

Intelligence Agency Headquarters in Langley, Virginia. It was one of his first

official actions as president and an opportunity to reset relations with the

intelligence community (IC). Just ten days prior, he had accused intelligence

agencies of helping to leak a report that claimed that Russian operatives had

his personal and financial information.

But Trump quickly

went off the rails, setting the tone for his relationship with the IC for the

rest of his first term. Standing in front of the CIA Memorial Wall—the agency’s

most important and solemn location—Trump offered remarks that resembled a campaign

event, rambling from one random topic to another, including how big the crowds

were at his inauguration. The juxtaposition of Trump’s complaints about the

media with the rows of stars representing agency staff who died in service

appalled many officers. It was an own goal that bred

suspicion and mistrust for the next four years.

As Trump prepares for

his second inauguration, the intelligence community is again likely to be ill

at ease. With a more organized and stable management team, the president-elect

could aim to harness the IC to secure the homeland and U.S. interests abroad.

But his nominations so far for director of the CIA, director of national

intelligence, and director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation suggest that

he is prioritizing loyalty over expertise. Driven by political grudges, Trump

might launch an all-out attack on what he has called the “deep state”: ostensibly

a secretive group of government bureaucrats collaborating to obstruct the Trump

agenda, including officers illegally spying on Americans and leaking

information to the media.

Agency officials

should try not to get caught up in Trump’s bluster. History shows that the IC

has often been able to succeed, even when it has had a difficult relationship

with the president. And despite Trump’s first-term flounders, he oversaw

important intelligence achievements, such as the killing of Islamic State

leader and founder Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

But the IC is likely

to face a range of risks during the next administration, including

to its personnel and organizations, collection and use of information,

authorities and missions, and foreign partnerships. It will have to navigate

near-term crises and avoid any longer-lasting damage to the community’s

institutions and capabilities. The IC can do so, in large part, by focusing on

its core objective: uncovering information that protects the country and thus

proving its essentiality. But it will have to work hard to ensure that tensions

with Trump remain petty bureaucratic fights rather than no-holds-barred brawls

that undermine American national security.

Draining the Swamp

Trump’s threat to the

intelligence community begins with its most basic resource: people. The

president-elect’s intent to curb the influence of the national security

bureaucracies and downsize the federal government is likely to drain the IC’s

human capital and, therefore, its overall effectiveness. Elon Musk and Vivek

Ramaswamy, Trump’s picks to lead a new Department of Government Efficiency,

have argued for a large-scale reduction of the federal workforce that would

inevitably affect intelligence workers. Trump himself has promised to fire what

he calls “corrupt actors” in national security.

It is still unclear

if and how reductions in the federal workforce would be applied to the

intelligence community. But if the Trump White House cuts too deeply, or makes

cuts in critical areas, it will undermine IC capabilities. Personnel

reductions, for example, could weaken skill sets that the IC is trying to grow

to address future threats from actors such as China, or in sectors such as

advanced technology. Even if he makes no cuts at all, Trump’s hostile rhetoric

could undermine the IC’s functionality. As in his first term, talented and

capable midlevel IC officers may leave rather than work for a president that

demands loyalty, a trend that will only be exacerbated by broader pressure on

civil servants.

Personnel losses are

difficult to replace in intelligence given the unique nature of the job, with

its specialized tradecraft, knowledge, and expertise. In October 1977, for

example, then CIA Director Stansfield Turner abruptly fired some 800 operations

officers, tanking morale at the agency and setting back human intelligence

operations for years to come. After the fall of the Soviet Union, IC personnel

were cut by 25 percent, the CIA budget declined by 18 percent, and the agency

instituted a hiring freeze for analysts, operations officers, and

technologists. The effect of these cuts reached into the late 1990s and into

the 2000s, hampering the IC’s ability to deal with the burgeoning threat from

global terrorism. Today, it might be even harder to replace lost staffers. In October 2021, CIA Director William Burns noted

that it took the CIA over 600 days, on average, to process and onboard new

officers. Trump could also deter qualified candidates from applying to begin

with. Few people, after all, will be thrilled about working for a president who

demonizes their jobs.

Even if Trump does

not cut the size of the IC, his reforms could worsen its human capital. Project

2025, the Heritage Foundation’s blueprint for the presidential transition,

argued that Trump should instruct his CIA director to replace the heads of

mission centers and directorates—the bodies that oversee agency work in

different areas—to ensure that the CIA’s activities align with the Trump

agenda. If this plan comes into being, many talented managers would likely be

replaced with officers viewed by the director as more loyal or partisan.

Project 2025 also called for permanently relocating parts of the agency outside

the Washington, D.C., region to lessen the CIA’s influence—an act that might,

again, push talented people out and disrupt the symbiosis between intelligence

and policy. The America First Policy Institute, a think tank founded in 2020 by

former Trump officials, has also proposed rules of conduct that would require

intelligence officers to sign an agreement not to “abuse their national

security credentials for political purposes,” even after leaving government

service. Such unclear and open-ended standards would probably breed risk

aversion in operations and analysis among IC staffers.

At a minimum, then,

the administration’s efforts will likely create churn that distracts the IC

from its primary missions. Even potentially useful reforms, such as giving the

director of national intelligence greater authority over the community’s budget,

would create turf battles among the 18 agencies in the IC. Leaders focused on

defending their resources and budgets—as well as their own jobs—are less likely

to effectively work together.

Chilling the Flow

During his first

term, Trump demonstrated disregard for the intelligence community’s output. He

posted a classified satellite image on Twitter. He publicly told agency heads

to “go back to school” after he disagreed with their annual threat testimony to

Congress on Iran. In his administration’s waning days, he absconded to

Mar-a-Lago with highly classified intelligence documents.

These tendencies

alarmed intelligence professionals. And,

unfortunately, there is a very good chance they will be back. Trump’s main

agency nominees, for example, share his disregard for the community’s output

and prize political loyalty. Director of National Intelligence nominee Tulsi

Gabbard is a longtime critic of U.S. intelligence findings. FBI director

nominee Kash Patel has created a list of “deep state” enemies to purge. Even

CIA director nominee John Ratcliffe, the least controversial of the three, has

a partisan track record. Ratcliffe is Trump’s former director of national

intelligence, and in early January 2021, the IC’s analytic ombudsman reported

that Trump-appointed intelligence officials, including Ratcliffe, had

politicized analysis on China’s and Russia’s interference in the 2020

presidential election. This week, Speaker of the House Mike Johnson replaced

Republican Representative Mike Turner as chair of the House Permanent Select

Committee on Intelligence because of, according to Turner, “concerns from

Mar-a-Lago.” Turner voted to ratify Biden’s election in 2020 and has been an

advocate for U.S. support for Ukraine. One member of Trump’s transition team

focused on the CIA, Robert Greenway, has argued that the president’s current

daily intelligence briefing, in which the intelligence agencies provide

coordinated assessments directly to the president, be replaced with a system

routed through lower-level White House political appointees. Such a system

would raise the odds that Trump hears only what he wants to hear, instead of

what he needs.

Should Trump and his

team behave with such disregard, their attitude toward the IC will likely lead

to weakened information sharing, with agencies restricting the flow of material

for fear that it may be misused. Intelligence officials are responsible for the

lives of human agents as well as for expensive, irreplaceable collection

platforms, and they may worry that the erosion of the protections for their

agencies’ information will put those lives and assets at risk. Doing so will

make it harder to connect the dots on key national

security challenges. The resulting consequences could be dire. For example, the

9/11 Commission report, released in 2004, found that failures in information

sharing (particularly between the CIA and FBI) were a major factor contributing

to the IC’s failure to uncover and prevent the attacks.

Even the perception

of politicization will increase the risks of self-censorship. Officers may

become hesitant to push forward information that does not align with the

president’s agenda. Alternatively, they may become more entrenched in their

original analyses, treating any other assessment as one intended to serve the

administration’s political interests rather than one objectively based on the

available information. This dynamic was present in the analysis of China’s

interference in the 2020 presidential election, according to the IC analytic

ombudsman’s January 2021 report. According to the ombudsman, CIA managers were

entrenched in their judgments that China had not attempted to undermine Trump

in the 2020 election and tried to suppress alternative assessments. Just like

the perception of a conflict of interest, the perception of politicized

intelligence can distort the analytic process, undermining debates essential to

solving difficult problems.

U.S. President Donald Trump at the Central

Intelligence Agency in Langley, Virginia, January 2017

Chilling the Flow

During his first term,

Trump demonstrated disregard for the intelligence community’s output. He posted

a classified satellite image on Twitter. He publicly told agency heads to “go

back to school” after he disagreed with their annual threat testimony to

Congress on Iran. In his administration’s waning days, he absconded to

Mar-a-Lago with highly classified intelligence documents.

These tendencies

alarmed intelligence professionals. And,

unfortunately, there is a very good chance they will be back. Trump’s main

agency nominees, for example, share his disregard for the community’s output

and prize political loyalty. Director of National Intelligence nominee Tulsi

Gabbard is a longtime critic of U.S. intelligence findings. FBI director

nominee Kash Patel has created a list of “deep state” enemies to purge. Even

CIA director nominee John Ratcliffe, the least controversial of the three, has

a partisan track record. Ratcliffe is Trump’s former director of national

intelligence, and in early January 2021, the IC’s analytic ombudsman reported

that Trump-appointed intelligence officials, including Ratcliffe, had

politicized analysis on China’s and Russia’s interference in the 2020

presidential election. This week, Speaker of the House Mike Johnson replaced

Republican Representative Mike Turner as chair of the House Permanent Select

Committee on Intelligence because of, according to Turner, “concerns from

Mar-a-Lago.” Turner voted to ratify Biden’s election in 2020 and has been an

advocate for U.S. support for Ukraine. One member of Trump’s transition team

focused on the CIA, Robert Greenway, has argued that the president’s current

daily intelligence briefing, in which the intelligence agencies provide

coordinated assessments directly to the president, be replaced with a system

routed through lower-level White House political appointees. Such a system

would raise the odds that Trump hears only what he wants to hear, instead of

what he needs.

Should Trump and his

team behave with such disregard, their attitude toward the IC will likely lead

to weakened information sharing, with agencies restricting the flow of material

for fear that it may be misused. Intelligence officials are responsible for the

lives of human agents as well as for expensive, irreplaceable collection

platforms, and they may worry that the erosion of the protections for their

agencies’ information will put those lives and assets at risk. Doing so will

make it harder to connect the dots on key national

security challenges. The resulting consequences could be dire. For example, the

9/11 Commission report, released in 2004, found that failures in information

sharing (particularly between the CIA and FBI) were a major factor contributing

to the IC’s failure to uncover and prevent the attacks.

Even the perception

of politicization will increase the risks of self-censorship. Officers may

become hesitant to push forward information that does not align with the

president’s agenda. Alternatively, they may become more entrenched in their

original analyses, treating any other assessment as one intended to serve the

administration’s political interests rather than one objectively based on the

available information. This dynamic was present in the analysis of China’s

interference in the 2020 presidential election, according to the IC analytic

ombudsman’s January 2021 report. According to the ombudsman, CIA managers were

entrenched in their judgments that China had not attempted to undermine Trump

in the 2020 election and tried to suppress alternative assessments. Just like

the perception of a conflict of interest, the perception of politicized

intelligence can distort the analytic process, undermining debates essential to

solving difficult problems.

Pushing the Boundaries

The politicization of

the IC comes with risks beyond just costing staff and fostering internecine

battles. Intelligence officials are likely to be concerned about the long-term

effect that Trump’s policies will have on their agencies’ roles and authorities,

leading to caution and hesitance that harm operational effectiveness. The CIA, in particular, has a long memory of operations pushed by

the White House that eventually blew back on the agency, such as the

Iran-contra scandal in the 1980s and the use of torture during the “war on

terror.” Both led to years of investigation and publicly dented the agency’s

reputation. Given Trump’s record of pursuing policies for personal benefit—his

first impeachment took place after he asked Ukrainian President Volodymyr

Zelensky to investigate Joe and Hunter Biden—intelligence officers are

especially likely to scrutinize his involvement in or direction of their

operations, worried that political motivations or overreach could land them

before Congress. Such reticence was already present during Trump’s first term.

According to Wired, Trump tried to enlist the CIA to overthrow

Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro, only to be met by tepid support and

unenthusiastic implementation from bureaucrats worried about the backlash.

Trump’s

unconventional foreign policy views and willingness to antagonize allies are

also likely to create challenges for intelligence sharing

with foreign partners. Project 2025 recommended that the White House seek more

control and oversight of foreign intelligence partnerships, rather than leaving

these under the control of the intelligence agencies. Trump’s nomination of

Gabbard has raised concern among U.S. allies, given her comparatively friendly

approach toward Russia and former Syrian President Bashar al-Assad (whom she

met in 2017). In July 2024, several foreign officials told Politico that

Trump advisers had informed them that the once and future president was

considering reducing intelligence sharing with NATO partners as part of a plan

to scale back support to the alliance. In May 2017, The New

York Times reported that Trump had even passed Israeli-derived

intelligence to Russia’s foreign minister in an Oval Office meeting.

Healthy intelligence

partnerships benefit the IC. Foreign governments gather and pass on insights

and information that U.S. agencies lack the access or resources to collect. But

if partners worry that the U.S. president or the director of national intelligence

will not protect what they share, or that it will be used in support of harmful

policies, they might stop. If so, it will not just be IC that suffers greatly.

Strained intelligence partnerships and reduced information sharing make it more

difficult for administration as a whole to use U.S.

intelligence as a policymaking tool, such as by providing it to allied

governments in support of initiatives. Washington, for example, warned of the

Russian invasion of Ukraine long before it happened in February 2022, helping

build momentum for powerful international sanctions.

Chilling the Flow

During his first

term, Trump demonstrated disregard for the intelligence community’s output. He

posted a classified satellite image on Twitter. He publicly told agency heads

to “go back to school” after he disagreed with their annual threat testimony to

Congress on Iran. In his administration’s waning days, he absconded to

Mar-a-Lago with highly classified intelligence documents.

These tendencies

alarmed intelligence professionals. And,

unfortunately, there is a very good chance they will be back. Trump’s main

agency nominees, for example, share his disregard for the community’s output

and prize political loyalty. Director of National Intelligence nominee Tulsi

Gabbard is a longtime critic of U.S. intelligence findings. FBI director

nominee Kash Patel has created a list of “deep state” enemies to purge. Even

CIA director nominee John Ratcliffe, the least controversial of the three, has

a partisan track record. Ratcliffe is Trump’s former director of national

intelligence, and in early January 2021, the IC’s analytic ombudsman reported

that Trump-appointed intelligence officials, including Ratcliffe, had

politicized analysis on China’s and Russia’s interference in the 2020

presidential election. This week, Speaker of the House Mike Johnson replaced

Republican Representative Mike Turner as chair of the House Permanent Select

Committee on Intelligence because of, according to Turner, “concerns from

Mar-a-Lago.” Turner voted to ratify Biden’s election in 2020 and has been an

advocate for U.S. support for Ukraine. One member of Trump’s transition team

focused on the CIA, Robert Greenway, has argued that the president’s current

daily intelligence briefing, in which the intelligence agencies provide

coordinated assessments directly to the president, be replaced with a system

routed through lower-level White House political appointees. Such a system

would raise the odds that Trump hears only what he wants to hear, instead of

what he needs.

Should Trump and his

team behave with such disregard, their attitude toward the IC will likely lead

to weakened information sharing, with agencies restricting the flow of material

for fear that it may be misused. Intelligence officials are responsible for the

lives of human agents as well as for expensive, irreplaceable collection

platforms, and they may worry that the erosion of the protections for their

agencies’ information will put those lives and assets at risk. Doing so will

make it harder to connect the dots on key national

security challenges. The resulting consequences could be dire. For example, the

9/11 Commission report, released in 2004, found that failures in information

sharing (particularly between the CIA and FBI) were a major factor contributing

to the IC’s failure to uncover and prevent the attacks.

Even the perception

of politicization will increase the risks of self-censorship. Officers may

become hesitant to push forward information that does not align with the

president’s agenda. Alternatively, they may become more entrenched in their

original analyses, treating any other assessment as one intended to serve the

administration’s political interests rather than one objectively based on the

available information. This dynamic was present in the analysis of China’s

interference in the 2020 presidential election, according to the IC analytic

ombudsman’s January 2021 report. According to the ombudsman, CIA managers were

entrenched in their judgments that China had not attempted to undermine Trump

in the 2020 election and tried to suppress alternative assessments. Just like

the perception of a conflict of interest, the perception of politicized

intelligence can distort the analytic process, undermining debates essential to

solving difficult problems.

Pushing the Boundaries

The politicization of

the IC comes with risks beyond just costing staff and fostering internecine

battles. Intelligence officials are likely to be concerned about the long-term

effect that Trump’s policies will have on their agencies’ roles and authorities,

leading to caution and hesitance that harm operational effectiveness. The CIA, in particular, has a long memory of operations pushed by

the White House that eventually blew back on the agency, such as the

Iran-contra scandal in the 1980s and the use of torture during the “war on

terror.” Both led to years of investigation and publicly dented the agency’s

reputation. Given Trump’s record of pursuing policies for personal benefit—his

first impeachment took place after he asked Ukrainian President Volodymyr

Zelensky to investigate Joe and Hunter Biden—intelligence officers are

especially likely to scrutinize his involvement in or direction of their

operations, worried that political motivations or overreach could land them

before Congress. Such reticence was already present during Trump’s first term.

According to Wired, Trump tried to enlist the CIA to overthrow

Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro, only to be met by tepid support and

unenthusiastic implementation from bureaucrats worried about the backlash.

Trump’s

unconventional foreign policy views and willingness to antagonize allies are

also likely to create challenges for intelligence sharing

with foreign partners. Project 2025 recommended that the White House seek more

control and oversight of foreign intelligence partnerships, rather than leaving

these under the control of the intelligence agencies. Trump’s nomination of

Gabbard has raised concern among U.S. allies, given her comparatively friendly

approach toward Russia and former Syrian President Bashar al-Assad (whom she

met in 2017). In July 2024, several foreign officials told Politico that

Trump advisers had informed them that the once and future president was

considering reducing intelligence sharing with NATO partners as part of a plan

to scale back support to the alliance. In May 2017, The New

York Times reported that Trump had even passed Israeli-derived

intelligence to Russia’s foreign minister in an Oval Office meeting.

Healthy intelligence

partnerships benefit the IC. Foreign governments gather and pass on insights

and information that U.S. agencies lack the access or resources to collect. But

if partners worry that the U.S. president or the director of national intelligence

will not protect what they share, or that it will be used in support of harmful

policies, they might stop. If so, it will not just be IC that suffers greatly.

Strained intelligence partnerships and reduced information sharing make it more

difficult for administration as a whole to use U.S.

intelligence as a policymaking tool, such as by providing it to allied

governments in support of initiatives. Washington, for example, warned of the

Russian invasion of Ukraine long before it happened in February 2022, helping

build momentum for powerful international sanctions.

Making Peace

Many intelligence

officers are undoubtedly anticipating Trump’s second term with trepidation,

remembering the bookends of his first four years—his inaugural CIA visit and

the Capitol insurrection. But IC officers have varying political views, and

when it comes to their work most are apolitical. Instead, they want to focus on

their mission: ensuring the safety and security of the American people.

If Trump wants to, he

can harness that focus and energy to secure the United States at home and

abroad. And with a less chaotic transition, and more experience, Trump is

better prepared to work with the IC this time than he was during his first term

in office. But Trump maintains a disdain for federal bureaucrats and holds an

enduring grudge about the investigation, led by the IC, into Russia’s

interference in the 2016 presidential election. And the path he is signaling,

through his rhetoric and appointments, is confrontation.

If Trump does

ultimately choose antagonism, U.S. intelligence agencies will face serious

challenges in executing their daily operations and in focusing on their core

missions. But intelligence professionals will still have a job to do, and

perhaps their best defense is to do it well. In 1961, the failed, CIA-led Bay

of Pigs invasion of Cuba nearly torpedoed the agency’s relations with newly

inaugurated President John F. Kennedy. But the following year, the IC regained

some of Kennedy’s trust after providing information that the Soviet Union was

delivering nuclear missiles to Cuba. Even skeptical, antagonistic presidents

often change their tune when they realize that they need the IC’s insight or

capabilities.

The IC also has

numerous oversight mechanisms it can use to make it harder for Trump’s team

misuses of intelligence—in ways that go beyond advancing policy objectives.

They are ones that have developed parallel to its

unique roles and authorities. Its sprawling, secretive bureaucracy does not

lend itself to White House micromanaging, particularly given that Trump is not

known for focus and persistence. Much of the IC’s work will continue in the

shadows, no matter what policies Trump pursues.

And ultimately,

Trump’s presidential term is only four years. He is full of bluster, but his

bark is often worse than his bite. The key for intelligence officials will be

to avoid distraction and find a way to stay focused on the core missions. By

doing so, they can ensure that Trump’s disruptions are temporary—not

a sea change for the community.

For updates click hompage here