Having published an

extensive five-part study of Russian

Freemasonry we now like to revisit our earlier topic of Freemasonry during

the fascist era.

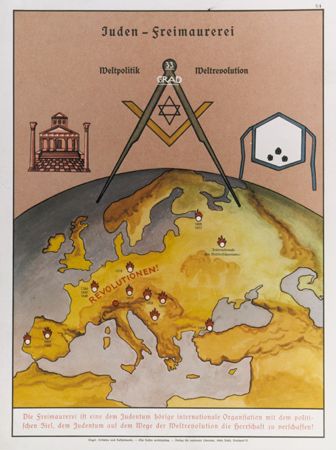

The text at the top

reads: "Jews-Freemasonry" followed by; "World politics World

revolution." The text at the bottom reads, "Freemasonry is an

international organization beholden to Jewry with the political goal of

establishing Jewish domination through worldwide revolution." The map,

decorated with Masonic symbols (temple, square, and apron), shows where

revolutions took place in Europe from the French Revolution in 1789 through the

German Revolution in 1919. (Printed by WWII NaziGovernement)

The notion of a

Judeo-Masonic conspiracy, for all its apparent virulence in the late nineteenth

and early twentieth centuries, could easily have turned out to be a fad – and

one marginal to the main currents of secular European ideology at that. Then

the First World War and the Russian Revolution pitched much of the continent

into turmoil: politics became more uncompromising and violent; nationalism more

frenzied in its hatred of internal enemies and scapegoats. When the First World

War ended, far-fetched, alarming schemes involving Masons and/or Jews became

more compelling than ever – as demonstrated by the most notorious version of

the Judeo-Masonic myth, a book that shaped it into a full-blown conspiracy

theory. First published in Russia in 1905, The

Protocols of the Elders of Zion purported to be a speech given at a secret

meeting in which Jewish leaders set out their plans to rule the world. In

reality, it more compelling than ever – as demonstrated by the most notorious

version of the Judeo-Masonic myth, a book that shaped it into a full-blown

conspiracy theory. First published in Russia in 1905, The Protocols of the

Elders of Zion purported to be a speech given at a secret meeting in which

Jewish leaders set out their plans to rule the world. In reality, it was as

much a fake as Taxil’s (G.A.Jogand-Pages) Palladism,

cooked up from a number of French novels in the 1890s. Freemasonry was

mentioned at various points in the Protocols. Like the press, international

finance, socialism, and pretty much everything else, the Craft was portrayed as

a tool of the great and despicable Jewish stratagem: ‘We shall create and

multiply free Masonic lodges in all the countries of the world, absorb into

them all who may become or who are prominent in public activity, for in these

lodges we shall find our principal intelligence office and means of influence.’

The Protocols of the

Elders of Zion was ignored outside Russia until translations

began to appear in 1920. Thereafter, despite strong evidence that it was a

fake, it became a hot topic of discussion internationally. In the United

States, automobile tycoon Henry Ford was a passionate advocate and funded a

vast print run – despite the fact that he was a Freemason. In Germany, the

Protocols found a ready audience on the nationalist right. The most prominent

believer was war hero General Erich Ludendorff.

After Germany’s defeat, he entered the political arena and spread the

‘stab-in-the-back’ myth. He believed – as well he might – that defeat was not

the fault of German generals. Instead, the blame lay on the home front, where

the army had been undermined by a grab-all list of back-stabbers among the

civilian population: the Jews were the worst, of course; but there were also

politicians and profiteers, strikers and shirkers, Catholics and Communists,

Marxists and – last but not least – Masons. Ludendorff had identified a lot of

enemies. And all of them were now in charge of the Weimar Republic. Or so he

claimed.

Adolf Hitler had been

a mere corporal during the war. He greatly admired General Ludendorff, and

embraced the stab-in-the-back myth wholeheartedly. There was precious little to

separate the two men ideologically: both were exponents of the racist version

of nationalism known as the völkisch ideology. They

met for the first time in Munich in 1922. The following year, Ludendorff,

wearing his military uniform and Pickelhaube (spiked helmet), took part in a

Nazi Party Putsch launched from a Munich Beer Hall. It was supposed to trigger

a ‘March on Berlin’ like Mussolini’s recent March on Rome. When the coup

failed, the former corporal Hitler went to prison. By contrast, the former

general Ludendorff was saved from a guilty verdict by his reputation.

Ludendorff, Germany’s

most prominent peddler of Masonic conspiracy myths, now had the opportunity to

assume leadership of the völkisch movement, Nazis

included. But he fluffed it. He was falling under the spell of his lover

Mathilde von Kemnitz, a nature-worshipping pagan who thought that not only

capitalism, Marxism, and Freemasonry were tools of the Jew, but even

Christianity. This was too much even for most Nazis. It was particularly obtuse

of Ludendorff to believe that his message would cut through in Catholic Bavaria

when he insisted on including the Jesuits, the Vatican and the church hierarchy

in his bulky catalog of traitors. The Nazi Party fissured among squabbling

factions.

Meanwhile, Adolf

Hitler’s stock began to rise. Despite its failure, the

Putsch, and especially the rousing speech that he was allowed to give at

his trial, increased his prestige. That prestige grew further when he loftily

withdrew from politics during his term in the Bavarian prison of Landsberg. He

devoted himself instead to drafting Mein Kampf, the memoir-manifesto that gave

definitive shape to his worldview. The book showed him to be a fervent believer

in the idea of a Judeo-Masonic conspiracy. The Jews, Hitler asserted, wanted to

‘tear down racial and civil barriers’ and so fought for religious tolerance. In

Freemasonry they found ‘an excellent instrument’ for this purpose: ‘The

governing circles and the higher strata of the political and economic

bourgeoisie are brought into [the Jews’] nets by the strings of Freemasonry,

and never need to suspect what is happening.’ So for Hitler, Masonry was an

underhand instrument of the Jew, a means to spread liberalism, pacifism, and

Jewish material interests.

When Hitler was

released in December 1924, he pointedly refused a lift back to Munich in

Ludendorff’s limousine. A few short weeks later, he re-launched the Nazi Party

with a set-piece speech in the Bürgerbräukeller, the

very beer hall where he had started his Putsch in November 1923. At eight

o’clock on the evening of 27 February 1925, a Friday, an audience of 3,000 was

crammed under the heavy chandeliers of the Bürgerbräukeller’s

cavernous grand hall; the balconies, hung with swastika banners, also heaved

with supporters; those at the back stood on barrels and chairs to catch a

glimpse. Over the next two hours, Hitler summarised

Mein Kampf. The German people, he argued, we're locked in a life-or-death

racial struggle with the evil of Jewry. ‘The Jew’,

who operated both by manipulating international finance and by stirring up

Marxism-Bolshevism, was a ‘world plague and epidemic’, a parasite in the

national body, a bacterium to be eliminated. Hitler was the man anointed by

destiny to lead his people in a coming racial conflict that could only have one

outcome: ‘either the enemy walks over our corpse, or we walk over his’.

The self-styled

Führer made no mention of the Freemasons. This is curious for several reasons.

Mussolini, from whom the Nazis were learning so much, had only just announced

his highly successful law against the Craft. As Mein Kampf showed, Hitler was a

convinced anti-Mason. The notion of a Judeo-Masonic conspiracy was hardly new

or unusual in 1925; it was political bread-and-butter for his supporters. So

why steer clear of the topic in the Bürgerbräukeller?

Anti-Masonry had

proved so addictive a mind-set since the French

Revolution partly because it contained ready-made counter-arguments to any

objections. Good Masons could be dismissed as dupes, caught up in a façade

erected by Grand Masters to hide their sinister plans. The repeated failure to

discover nasty secrets in the Lodges did not matter, because the real danger

lay in the hidden Lodges. Somehow, the true face of this evil never quite came

into focus. The Masons seemed all the more cunning and pervasive as a result.

To Hitler, this strength of

anti-Masonry was also a weakness: it made the enemy’s outlines too fuzzy.

He needed to make the phantasmagorical threat to his equally phantasmagorical

Aryan race seem real, biological. There could be no excuses, no margin of

doubt, no fiddly process of sorting out the innocent from the guilty. He hated

Freemasonry, but to let any attack on it clutter the call for a war on Jews

would be to rob his ideology of its brutal simplicity. His political instincts

trumped his fanaticism, telling him that hatred of Freemasonry was a flexible

tool, to be deployed as and when it was useful to spread doubt and confusion.

Hitler’s anti-Masonry exemplified his ability to combine fanaticism with

pragmatism: his overarching, obsessive hatred of ‘the Jew’ allowed other

components of his ideology, notably anti-Communism, to be deployed when they

would be most popular and have the most impact.

So instead of talking

about Freemasonry that evening at the Bürgerbräukeller,

Hitler made some trenchant remarks on strategy. It was necessary to simplify

things for the masses, ‘to choose only one enemy so that everyone can see that

this alone is the culprit’. The single enemy he had in mind was, of course, the

Jews, and the ‘Jewish Bolshevism’ that he saw as their preferred political

guise. But as the Nazis in the hall were well aware, the remark about strategy,

and the silence on Freemasonry, were a sideswipe at one particular man who was

absent that night: Hitler’s celebrity rival, General Erich Ludendorff, whose

obsession with Freemasonry made him pick on too many enemies.

After the Bürgerbräukeller speech, the Nazi leader wasted no time in

executing his next move. A few days later he lured General Ludendorff into a

trap by flattering him into putting his blathering ideology to the national

electorate as the Nazi candidate in the presidential elections.

The result was an

abrupt humiliation: Ludendorff polled only just over 1 percent, putting him

well on the way to political oblivion.

The following year,

Ludendorff married Mathilde von Kemnitz, and the couple dived deep into a

bottomless ocean of racial mysticism and conspiratorial delusion. Mathilde

would eventually come to believe that the Freemasons, and even those

arch-schemers the Jews, were themselves puppets in the hands of the Dalai Lama,

who pulled their strings from a laboratory in Tibet. Her husband, the former

national hero, became a national embarrassment in the press. In 1927, he

published his major work on the Craft, The Annihilation of Freemasonry through

the Revelation of its Secrets: it claimed that Masonic rituals trained Brothers

to be ‘artificial Jews’,

and that the reason they wore aprons was to disguise the fact that they had

been circumcised. This was barmy even by the standards of the Masonic exposé

genre. But it did not stop it selling in the thousands – about 180,000 by 1940,

in fact. Hitler, who by this time felt able to treat his defeated political

rival with contempt, responded to the book by accusing Ludendorff of being a

Mason.

It should hardly need

saying that German Freemasonry could not wield remotely the kind of influence

that Ludendorff and Hitler alleged.

In 1925, when Hitler

gave his Bürgerbräukeller speech, there were 82,000

Masons in 632 Lodges. Masons in Germany tended to be lawyers, teachers, civil

servants, businessmen, Protestant clergy and the like. But they were even more

divided than their Italian Brothers: they worked under the authority of no

fewer than nine different Grand Lodges – including the Hamburg Grand Lodge we

visited earlier. These divisions had grown markedly worse amid the polarised politics of the 1920s. The issue of Jewish

membership was the main source of the quarrel.

Contrary to what a

nostalgic strain of Masonic history-writing would have us believe, most German

Masons were not morally opposed to Nazism in the name of tolerance. Indeed,

they were increasingly becoming supporters of the völkisch

agenda. Freemasons today might want to believe that their Brotherhood stood by

its values in the face of Hitler’s terror; the miserable truth of what happened

proves them wrong – as the best Masonic historians have now documented with

impartial rigor. The history of the Jews’ relationship with Freemasonry really

begins in the late eighteenth century, when communities in various European

countries made their first moves towards embracing the secular values of the

Enlightenment. At the same time, European states began to give Jews more civil

rights. The Lodges were a natural halfway house for Jews inclined towards

assimilation, because of the tolerant attitude to race and religion expounded

by Masonry’s British founding fathers. Masonic symbols also felt accessible to

Jews: many of them were either non-religious (like the square and compass) or

came from the Old Testament (like Solomon’s Temple).

During the nineteenth

century, the process of integrating Jews into Freemasonry went in fits and

starts, in different times and places. When Germany was united in 1871, the

Masonic orders from the different pre-unification states, with their

distinctive approaches to Jewish membership, did not merge; instead, they

established an uneasy way of recognizing one another and cohabiting under a

weak umbrella body. The rise of anti-Semitism and völkisch

ideas towards the end of the century put that cohabitation under strain.

On one side were six

Grand Lodges known as the Humanitarian Grand Lodges. Brothers who recognized

the authority of the Humanitarian Grand Lodges tended to be from the center and

centre-Left of the political spectrum and to be open

to accepting Jews. Hamburg Grand Lodge was Humanitarian. However, a large

majority of Freemasons – roughly 70 percent – came under the auspices of three

Grand Lodges known collectively as the Old Prussian Grand Lodges, which were

more historically prestigious. The Old Prussians were also avowedly

anti-Semitic and regarded the Humanitarian Lodges as dangerous centers of

‘pacifist and cosmopolitan’ thinking. A great many Freemasons in Old Prussian

Lodges sympathized with the völkisch extreme Right of

the political spectrum where the Judeo-Masonic conspiracy myth found its

natural home. In May 1923, an Old Prussian Lodge in Munich invited Ludendorff

himself to an evening of ‘enlightenment’ for members of the public. The Lodge’s

Master was of the opinion that Masonry should have a ‘racist base’, and wanted,

therefore, to persuade a racist like Ludendorff that the Craft was a friend and

not a foe. Ludendorff accepted the invitation while remaining steadfast in his

anti-Masonic delirium.

In 1924, an Old

Prussian Lodge in Regensburg adopted the Nazi swastika as its badge. From 1926

– still long before Hitler came to power – two of the three Old Prussian Grand

Lodges began to consider reforming their rituals, removing suspiciously Jewish

Old Testament references and substituting robustly ‘Aryan’ symbols sourced from

Teutonic folklore. When the Old Prussian Grand Lodges heard accusations that

they were a tool of the Jews, they proudly indicated that they did not have a

single Jewish member – thereby pointing the finger at their Brothers in the

more tolerant Humanitarian Lodges.

The Humanitarian

Lodges responded lamely that ‘only’ about one in eight of their members was

Jewish. (For what it is worth, this number was about four times larger than the

proportion of Jews in the population as a whole – although Jews were more

numerous among the upper-middle strata of the population from which Lodge

members tended to come.) At this time, more and more Humanitarian Lodges were

switching their allegiance to the anti-Semitic Old Prussian Grand Lodges. Even

in many of the remaining Humanitarian Lodges, the climate became more

nationalistic. Jewish Brothers understandably felt exposed; they deserted the

Craft in droves in the late 1920s. By 1930 – still, three years before Hitler

took power – the proportion of Jewish Freemasons in Humanitarian Lodges had

fallen from one in eight to one in twenty-five.

The Nazis were now

growing in popularity against the background of a calamitous economic downturn

precipitated by the Wall Street Crash. While remaining focused on the Jews and

their supposed Communist puppets as a national enemy, the Nazis aimed the occasional

intimidating noise at the Craft. In the summer of 1931, Hitler urged Nazi Party

members to photograph the Freemasons they encountered and make a record of

where they lived.

In response, one Old

Prussian Grand Lodge tried to open a personal channel of communication to the

Nazi leadership, in the person of Hermann Göring, whose half-brother was a

Mason. The aim was once again to try to save the Old Prussian Lodges by

branding the Humanitarian Lodges as suspect. The attempt failed, and Göring

snubbed the Masons’ emissary. Despite this setback, the Old Prussian Lodges

were moving closer and closer to Hitler. In the summer of 1932, one of the Old

Prussian Grand Lodges, the Grand National Lodge of Freemasons of Germany,

issued a declaration that might just as well have been penned by Hitler’s

campaign manager, Joseph Goebbels. ‘Our German Order is völkisch,’

it affirmed, before going on to decry the ‘slimy, murky waters’ of

humanitarianism, and the ‘mixture and degeneration of all cultures, art forms,

races, and peoples’. We should be clear about what was happening to German

Masonry. It was not just a question of Craftsmen reflecting the climate of

middle-class opinion in the country at large. In other words, they were not

just spooked by Communism and hankering after more order, although that is

undoubtedly part of the story. Many of them envisaged a leading role for their

Brotherhood in implementing völkisch ideas. They

wanted to convert Masonry’s traditional ethical mission of building better men

into a program to build a purer and more aggressive Aryan race, free of Jews.

Freemasonry and Aryanisation

On 27 February 1933,

exactly eight years after the Nazi rally in the Bürgerbräukeller,

a Dutch bricklayer by the name of Marinus van der Lubbe gave Hitler, newly

appointed as Chancellor (Prime Minister), the chance to turn his coalition

government into a totalitarian regime. Unemployed and homeless, Van der Lubbe

vented his frustrations by burning down the Reichstag. The Nazis dressed the

incident up as the beginning of a Communist coup. On this pretext, a decree was

passed that drastically curtailed civil liberties. Soon afterward, an Enabling

Act amended the constitution to allow Hitler to introduce any laws he liked,

without consulting the Reichstag or the President. The dictatorship had begun.

The first of Nazism’s enemies to be targeted were the Communists, who fell

victim to a tornado of beating, torture, and murder. Then it was the turn of

the Social Democrats and trade unions to endure the wrath of Hitler’s SA: these

brown-shirted ‘stormtroopers’ were a Nazi army of four hundred thousand.

Makeshift penal camps, private Nazi prisons for political detainees, were set

up. No law applied here: prisoners could be robbed, raped, sadistically

tortured, or shot ‘while trying to escape’. The Catholic Centre Party was the

last opposition party to be crushed. Then came Hitler’s coalition allies, the

Nationalists.

As soon as he had

incapacitated the Nazis’ political rivals, Hitler turned to anyone or anything

that threatened to stand in the way of creating a Nazi society. Like clinics or

lobby groups that advocated sexual health, contraception, or homosexual rights.

There was a crackdown on suspected gangsters and vagrants. Local mayors were

forcibly deposed; hospitals, law courts, and other public institutions invaded.

Associations representing the interests of farmers, entrepreneurs, women,

teachers, doctors, doctors, sportsmen, and even disabled war veterans were

taken over and turned into tame emanations of the Nazi Party, with no Jews

allowed. Synagogues were raided, pillaged, and burned. Jews were attacked in

the street. The civil service was ‘Aryanised’,

meaning that Jews lost their jobs. Jewish and politically suspect university

professors were sacked. Jews were expelled from orchestras and art academies,

radio stations, and cinema production companies. Where the brownshirts led,

legislation followed. By the summer of 1933, Germany was a one-party state, and

the path to Hitler’s racial dystopia had been traced out.

And the Freemasons?

They certainly did not suffer the kind of systematic brownshirt assault endured

by Hitler’s left-wing enemies and the Jewish population. Hitler had his

priorities, and they were not the same as Mussolini’s had been in 1925, at the

equivalent stage in the establishment of the Fascist dictatorship. The

Freemasons were a long way from the top of the Nazi list. Even jazz musicians

were considered a greater annoyance. Nevertheless, there were sporadic attacks

during those first months – albeit nothing like as violent as in Italy. At one

Düsseldorf Lodge on 6 March 1933, five uniformed stormtroopers followed by a

gang of men in civvies knocked at the door and demanded to see the Lodge’s

records. When asked to provide some proof of their identity, they replied,

‘Loaded pistols are our authority’ and forced their way in. They smashed the

lock of the cupboard where the records were kept and began loading the papers

into a waiting lorry. But they withdrew quietly when they were told that the

Lodge was in mourning for a dead Brother. In August, in Landsberg, an der Warthe in Prussia, the members of one Lodge were

bullied into unanimously voting to hand over all their assets to a local

brownshirt unit.

An insidious threat

to Freemasonry came from informers – Masons who were happy to betray their

fraternal oaths to win favor with the regime. They told the Nazis all kinds of

tales about the goings-on in the Lodges. Whether out of enthusiasm for Nazi

ideology, or out of fear, individual Masons began to desert the Brotherhood,

and the temples to fall silent. In Hamelin in Lower Saxony, one Lodge Master

surprised his Brethren by appearing at a meeting in SS uniform and ordering

that the Lodge be disbanded. Masonic leadership rapidly lost all confidence. As

early as the spring of 1933, German Freemasonry was falling apart.

In response to the

crisis, all three Old Prussian Lodges united to send a letter to Hitler on 21

March 1933 – the ‘Day of Potsdam’ when the regime mounted a national

celebration to mark its seizure of power. The letter assured that the Lodges

would stay true to their ‘national and Christian tradition’ and be

‘unswervingly most loyally obedient to the national government’. The hope was

that they would be able to trade political loyalty for some kind of official

endorsement. In early April, the Grand Masters finally succeeded in sitting

around a table with Herman Göring. Things did not go as they had hoped. Göring

banged his fist on the table and roared, “You damned pigs, I need to

throw you and this Jew-band in a pot!...there is no room for Freemasonry in the

National Socialist State.”

The endgame had

begun. Sooner or later, the Nazis would follow the Italian Fascists in banning

Freemasonry.

Shortly after the

meeting with Göring, one of the three Old Prussian Grand Lodges adopted the

swastika as its symbol. Another tried its own ingenious solution to the

problem, by ceasing to be Masonic. It abandoned its old name, the ‘Grand

National Lodge of Freemasons of Germany’, and became the ‘German Christian

Order’; its constitution stipulated that ‘only Germans of Aryan descent’ could

be members. All references to Jewish and Masonic symbolism and vocabulary were

canceled from the statutes. ‘We are no longer Freemasons’, one circular

announced. The other Old Prussian Grand Lodges soon united behind this move.

The Humanitarian

Grand Lodges were less coordinated. Three of them, based respectively in

Darmstadt, Dresden, and Leipzig, followed the Old Prussian Lodges by expelling

Jews and ceasing to call themselves Masonic. Another Humanitarian Grand Lodge,

the Frankfurt-based Eclectic Union, dissolved itself at around the same time,

but then immediately re-formed in an Aryanised

version, probably with the intention of saving its real estate from

confiscation. The Grand Master of another Grand Lodge, the Bayreuth Grand Lodge

of the Sun, announced on 12 April 1933 that the order was Aryanising,

and politely asked Jewish Brethren to resign – thanking them in advance for

their selfless gesture. Only six days later, the Grand Master decided that this

was futile, and opted for the only realistic way to maintain the Masonic

dignity of his order in the circumstances: he dissolved the Grand Lodge, asking

all the subordinate Lodges to follow suit.

By the autumn of

1933, although it had not been officially banned by the regime, Freemasonry in

Germany was a shell. The surviving former Grand Lodges, now Aryanised

and reconstituted as German Christian Orders, remained subject to uncoordinated

attacks and confiscations. Yet they still hoped that by kowtowing they might

earn some form of state recognition. One of the reasons why this hope

persisted, and why the Nazis took much longer to stamp out Freemasonry than did

the Italian Fascists, was exactly the reason that Hitler had intuited back at

the Bürgerbräukeller in 1925 when he chose to focus

on a single enemy: deciding just who was and who was not a Freemason was a

confusing business. In the eyes of the Nazis, the creation of the German

Christian Orders could just be the Freemasons’ latest devious ruse. The issue

did not just affect the matter of whether to ban Masonry. What about all the

former Freemasons around? Many were also members of organizations that had now

been incorporated into the Nazi state. So should they be expelled? Or barred

from holding government jobs? Where should the line be drawn? Between the

former Old Prussian Lodges and the former Humanitarian Lodges? Or between those

who had given up their Masonic ways before the Nazi seizure of power, and those

who had only conformed afterward? In some places, the Gestapo suspended

anti-Masonic lectures because they thought they were attracting unwanted

followers of the aged General Ludendorff. The confusion increased because the

SA, the SS, the Gestapo, and other agencies and individuals within the Nazi

state jockeyed for control of what was becoming known as the ‘Freemasonry

Question’ – and therefore of the right to plunder the Lodges. For a while, in

January 1934, the Führer even suspended measures against Freemasonry to ease

the tussling within the Nazi movement. Loyal as ever, the former Old Prussian

Grand Lodges chose to interpret this as a hopeful sign. They also saw hope in

the fact that a former Freemason by the name of Hjalmar Schacht served in

Hitler’s government as President of the Central Bank and then Minister of

Economics.

In Hitler’s mind, the

political calculation was temporarily outweighing his anti-Masonry, just as it

had done in 1925. Some grassroots Masons saw more clearly that the end was

nigh. Walter Plessing, like his father and grandfather before him, was a member

of an Old Prussian Lodge in Lübeck on the Baltic coast. In September 1933, he

resigned in order to join the Nazi Party and succeeded in becoming a

stormtrooper. A few months later, when it was discovered that he had been a

Mason, he was forced to leave the party. In March 1934, when he heard that he

would be forced out of the SA too, he committed suicide,

bequeathing all his money to Hitler. His suicide note protested at being

treated as a traitor and a ‘third-class German’; neither he nor his former

Lodge had any ‘connection with Jews or Jewry’.

Nazi Policy on Masons

only became unequivocal after July 1934 and the Night of the Long Knives – the

savage purge of the SA and other political enemies. Thereafter, the SS assumed

control of the Masonic Question. In October 1934, a recent recruit to the SS

intelligence agency, Adolf Eichmann, was given the first test of his

administrative skills: he was told to compile a central index of Masons. Having

convinced his superiors of his talents, he was moved to the SS department

responsible for Jews, where he would go on to play a notorious logistical role

in implementing Hitler’s ‘Final Solution’ to the ‘Jewish Question’.

In the spring of

1935, finally, the former Masonic organizations were told to dissolve

themselves completely or be forced to do so. Either way, their assets would be

confiscated. The Grand Masters agreed to this recommendation, on condition that

the Craft was publicly absolved of all the accusations of disloyalty that had

been made against it. No such absolution was ever granted. The self-dissolution

went ahead anyway during the summer.

All of which brings

us back to the mournful scene with which this story began: the final closure of

the Grand Lodge in Hamburg, to the sound of weeping Brothers and of Mozart’s

The Magic Flute. Hamburg, long a center of a more liberal form of Masonry, was

a Humanitarian Grand Lodge – one that admitted Jews, therefore. To his credit,

before the Nazis assumed power, Grand Master Richard Bröse did seek to parry Hitler’s attacks. He chose

transparency as his shield. In August 1931, he wrote a public letter to Hitler

offering to grant open access to the Grand Lodge’s archives to any investigator

mutually agreed between the two of them. Furthermore, he pledged to close the

Grand Lodge down if it was found that Masonry had ever done anything against

the national interest.

Bröse’s attempt was doomed. No amount of transparency can

reassure a conspiracy theorist. Hitler did not reply. Instead, the task was

taken up by senior Nazi ideologist Alfred Rosenberg, who dismissed Bröse’s offer as a typical Masonic deception; the Nazis

regarded all Masons as traitors, he scoffed.

Once Hitler had taken

power, Bröse betrayed his order’s tolerant values as

fast as any other Humanitarian Grand Master. On 12 April 1933, he announced

that the Grand Lodge was open only to ‘German men of Aryan descent and

Christian religion’. It was in this Aryanised form

that the Hamburg Grand Lodge shut down, under the eyes of the Gestapo, in the

summer of 1935. Clearly, the tale of the closure of the Hamburg Grand Lodge as

Masons tend to recount it omits one painful detail: the Craftsmen present in

the Hamburg temple that night had already abandoned all trace of Masonic values

and embraced Nazi racism in a futile attempt to ensure their survival as a

Christian-only fellowship. Mozart would have turned in his grave.

No historian will

ever be able to reconstruct the exact mixture of emotions that led Bröse and his Brothers to shed such copious tears on that

evening in Hamburg in July 1935. Certainly a sense of loss and injustice. Fear

and frustration too, most likely. It may also be that another feeling clouded

their eyes as the last rites of their Brotherhood were performed: shame. The

only Masonic group that voiced opposition to Hitler in the name of Masonic

values was neither a Humanitarian nor an Old Prussian Lodge. The Symbolic Grand

Lodge of Germany was formed in 1930 when some Masons who were determined to

stand against the anti-Semitic tide broke off from the Humanitarian Lodges.

Virtually alone among German Masonry’s leadership, the Grand Master of the

Symbolic Grand Lodge, a lawyer called Leopold Müffelmann,

resisted courageously, continuing to criticize Nazism even after Hitler took

power. Then on 29 March 1933, in public, he declared the dissolution of his

Grand Lodge, while taking measures to ensure that it could continue to work in

secret. However, within a few weeks, Müffelmann had

to recognize that the situation was too dangerous. So in June 1933, at a secret

meeting in Frankfurt, he and the other leaders of the Symbolic Grand Lodge of

Germany decided to transfer their base to Jerusalem, and try to survive in

exile.

On 5 September, Müffelmann was betrayed by an informer and arrested in

Berlin. He was interrogated by the Gestapo before being sent to the

stormtroopers’ penal camp at Sonnenburg. There he was beaten and forced to do

hard labor, despite having a serious heart condition. He died in August 1934 as

a result of his ordeal. Müffelmann and those who

shared his vision of Masonry were, it should be stressed, a tiny minority of

fewer than two thousand at the peak. What is more, they were a minority that

the institutions of mainstream Freemasonry, both the Old Prussian and the

Humanitarian Grand Lodges, categorically refused to recognize as legitimate

Masons. So as one historian has pointed out, it is misleading of Freemasons to

treat the Symbolic Grand Lodge of Germany as a ‘poster child of Masonic

victimization and courageous resistance’.

Grand Master Müffelmann was one of the few Masons to be persecuted as a

result of his activity within the Craft. Indeed, vast ambiguity clouds most of

the victims of Nazism that Freemasonry claims as its own – whether they are

80,000, or 200,000, or any other number. Take the case of Carl von Ossietzky,

who was arrested within hours of the Reichstag fire. Deprived of food, he was

forced into hard labor, and beaten and kicked by camp guards who yelled ‘Jewish

pig’ and ‘Polish pig’ at him. (As it happened, he was neither Jewish nor

Polish.) By November 1935, when he was seen by a Red Cross visitor, Ossietzky

was ‘a trembling, deadly pale something, a creature that appeared to be without

feeling, one eye was swollen, teeth knocked out, dragging a broken, badly

healed leg … a human being who had reached the uttermost limits of what could

be borne’. It is a testament to his endurance that he only finally succumbed

eighteen months later, in May 1938.

Ossietzky was both a

Freemason and a victim of Nazism. But he was not victimized because he was a

Freemason. He was killed because he was a left-wing intellectual, a prominent

journalist and critic of Nazism, and a pacifist who had reported Germany’s illegal

rearmament program to the international community. He was awarded the Nobel

Peace Prize while in a concentration camp in 1936.

How many Freemasons

died under the Nazi regime? The research has yet to be done. But it seems very,

very unlikely that the total of Masons murdered reached as many as 200,000.

That would represent a staggeringly high percentage of the total number of Masons

in countries occupied by German forces in the Second World War. What is certain

is that the vast majority of those who did die were not killed because they

were Masons, but above all because they were Jews. Austria, which became part

of the Third Reich in the Anschluss of March 1938, is probably typical. When

Nazi forces marched in, there were 800 Masons in Austria. The Vienna Grand

Lodge was raided and the Grand Master arrested; already ill, he died in

custody. The Nazis rapidly proceeded to abolish Freemasonry in Austria as they

had done in Germany. It has been calculated that between 101 and 117 Brothers

were murdered before 1945. Another 13 committed suicide; 561 went into exile.

But these figures only make sense when we realize that most Catholic Masons had

resigned before the Germans marched in. Hundreds of them had already abandoned

the Craft after 1933 because of harassment by the Catholic-Fascistic government

that preceded the Nazis. Left behind in the Lodges when the Nazis arrived in

1938 were many Jews – two-thirds of that total of 800.

Although the Nazi

state in Germany crushed Freemasonry, it did not persecute individual

Freemasons with remotely the same lethal fanaticism as it did other groups.

Mein Kampf, after all, had given non-Jewish Craftsmen an escape clause.

Hitler’s memoir had said that ordinary Masons ‘never needed to suspect’ that

the Jews were really in charge behind the scenes. So, in the overwhelming

majority of cases, it was enough for a Brother to recant for him to dodge the

jackboot and the concentration camp. Even the institutional discrimination

against former Masons was lifted, as many Masons with qualifications and skills

showed they could be loyal and useful members of Nazi society.

The reasons why

Masons have exaggerated what they endured at Hitler’s hands are not hard to

discern. The Nazis are Hollywood’s favorite bad guys. Contrasted against the

pitch-black evil that they represent, the Masonic tradition seems to shine more

nobly. But Masonry’s misleading memories of Nazi repression do a disservice to

those who were far more ruthlessly targeted by Nazism: it is as if the Craft

were trying to get a foot on the pedestal of history’s greatest victims.

Perhaps more tellingly, those Masonic identity narratives draw attention away

from a regime that was far more brutal and thorough in its persecution of

Freemasonry than were Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany: the Spain of

General Francisco Franco.

Sources:

Munich: The Beer-Hall strategy I. Abrams, ‘The

multinational campaign for Carl von Ossietzky’. A paper presented at the

International Conference on Peace Movements in National Societies, 1919–39,

held in Stadtschlaining, Austria, 25–9 September

1991, consulted at: http://www.irwinabrams.com/articles/ossietzky.html

on 16/1/20: ‘a trembling, deadly pale something …’

H. Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem, London, 1963. Arendt

(pp. 28–9) mentions that Eichmann tried to join ‘the Freemasons’ Lodge Schlaraffia’ in Austria early in 1932 before he joined the

SS. However, Schlaraffia is not a Masonic organisation, and has more frivolous aims.

M. Berenbaum (ed.), A Mosaic of Victims, Non-Jews

Persecuted and Murdered by the Nazis, New York, 1990.

D.L. Bergen, War and Genocide: A Concise History of

the Holocaust, New York, 2003.

C. Campbell Thomas, Compass, Square and Swastika:

Freemasonry in the Third Reich, PhD thesis, Texas A&M University, 2011. On

Masonic informers, p. 76. On the 2,000 membership of Leopold Müffelmann’s strand of Masonry, p. 48. ‘Poster child of

Masonic victimization and courageous resistance’, p. 17.

R.J. Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich, London,

2003. Evans and Kershaw (below) provide a good context of Freemasons and Nazi

repression.

R.J. Evans, The Third Reich in Power, 1933–1939: How

the Nazis Won Over the Hearts and Minds of a Nation, London, 2006. On Carl von

Ossietzky, passim.

R.J. Evans, The Third Reich at War: How the Nazis Led

Germany from Conquest to Disaster, London, 2008.

A. Hitler, Mein Kampf, translated by R. Manheim,

London, 1992 (1943). On Freemasonry, p. 285.

A. Hitler, ‘Rede Hitlers zur Neugründung der NSDAP am 27. Februar 1925 in München’: http://www.kurt-bauer-geschichte.at/lehrveranstaltung_ws_08_09.htm. ‘Either the enemy walks over our corpse’, p. 6. On the

importance of a single enemy, p. 7.

C. Hodapp, Freemasons for Dummies, Hoboken, NJ, 2013.

The implausible claim of 200,000 Masons killed by the Nazis is on p. 85. It

should be said that Hodapp is an engaging and fair-minded Masonic writer, and

this introduction is recommended.

E. Howe, ‘The Collapse of Freemasonry in Nazi Germany,

1933–5’, AQC, 95, 1982. On sales of Ludendorff’s book, p. 26. On the attacks on

Lodges in Düsseldorf and Landsberg an der Warthe, pp.

29 and 32. Suicide of Walter Plessing, p. 33.

J. Katz, Jews and Freemasons in Europe, 1723–1939,

Cambridge, MA, 1970. On The Protocols, pp. 180–94. On the proportion of Jews in

German German Lodges, pp. 189–90.

I. Kershaw, Hitler: 1889–1936: Hubris, London, 1998.

On Hitler’s speech at the Bürgerbräukeller in 1925,

pp. 266–7. Hitler accuses Ludendorff of being a Mason, p. 269. On Hjalmar

Schacht, p. 356 and passim.

I. Kershaw, Hitler 1936–45: Nemesis, London, 2000.

R.S. Levy (ed.), Antisemitism: A Historical

Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, Santa Barbara, CA, 2005, vol. 2.

Entry on The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, pp. 567–70.

E. Ludendorff, Destruction of Freemasonry Through

Revelation of Their Secrets (trans. J. Elisabeth Koester), Los Angeles, 1977.

Masonic Encyclopedia, ‘Österreich 1938–1945: 692 Freimaurer wurden Opfer des

Nazi-Terrors’, which summarises research on the Nazi

repression of Masonry in Austria. Österreich

1938-1945: 692 Freimaurer wurden

Opfer des Nazi-Terrors – Freimaurer-Wiki

R. Melzer, ‘In the Eye of a Hurricane: German

Freemasonry in the Weimar Republic and the Third Reich’, Totalitarian Movements

and Political Religions, 4 (2), 2003. For the number of Masons and Lodges in

1925, p. 114.

R. Melzer, Between Conflict and Conformity:

Freemasonry during the Weimar Republic and Third Reich, Washington DC, 2014.

Offers a systematic and authoritative study. May 1923, an Old Prussian Lodge

invited Ludendorff, p. 85. Old Prussian Lodge in Regensburg adopted the Nazi

swastika as its badge, p. 157. In 1926, two of the three Old Prussian Grand

Lodges considered introducing ‘Aryan’ symbols, p. 81. Göring snubbed the

Masons’ emissary, pp. 99–100. ‘Our German Order is völkisch’,

quoted pp. 95–6. In Hamelin Lodge, a Master appears in SS uniform, p. 177.

Letter to Hitler offers assurance that the Lodges would stay true to their

‘national and Christian tradition’, quoted p. 151. ‘You damned pigs, I need to

throw you and this Jew-band in a pot!’, quoted p. 153. Lodges adopt swastika as

symbol, p. 159. ‘Grand National Lodge of Freemasons of Germany’ becomes ‘German

Christian Order’, p. 154. ‘We are no longer Freemasons’, quoted p. 156.

Humanitarian Lodges Aryanised, pp. 162–72. Confusion

and hesitancy in Nazi policy, pp. 188–91. On Adolf Eichmann, p. 188. Hamburg

Grand Lodge only open to ‘German men of Aryan descent’, quoted p. 170. On

Leopold Müffelmann, pp. 173–5.

S. Naftzger, ‘“Heil Ludendorff”: Erich Ludendorff and

Nazism, 1925–1937’, PhD thesis, City University New York, 2002. On von Kemnitz,

pp. 23–30 and passim.

R.M. Piazza, ‘Ludendorff: The Totalitarian and Völkisch Politics of a Military Specialist’, PhD thesis,

Northwestern University, 1969.

L.L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich, London,

1976. For the SA and its numbers, p. 304.

R. Steigmann-Gall, The Holy

Reich: Nazi Conceptions of Christianity, 1919–1945, Cambridge, 2003. On

Ludendorff, pp. 87–91.

C. Thomas, ‘Defining “Freemason”: Compromise,

Pragmatism, and German Lodge Members in the NSDAP’, German Studies Review, 35

(3), 2012.

P. Viereck, Metapolitics: The Roots of the Nazi Mind,

New York, 1961 (1941). On Mathilde von Kemnitz, p. 297.

For updates click homepage here