By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Deterring the Nuclear Dictators like

China, Russia, and North Korea

For more than three

decades after the end of the Cold War, the United States and its allies faced

no serious nuclear threats. Unfortunately, that is no longer the case. Russian

President Vladimir Putin has been rattling his nuclear saber in a manner

reminiscent of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. Chinese President Xi Jinping

has directed a dramatic buildup of China’s nuclear arsenal, a project whose

size and scope the recently retired commander of U.S. Strategic Command has

described as “breathtaking.” The Russian and Chinese leaders have also signed a

treaty of “friendship without limits.” North Korean leader Kim Jong Un is

supplying weapons and troops to support Russia’s war in Ukraine, and North

Korea is improving its ability to strike both its neighbors and the U.S.

homeland with nuclear weapons, as it demonstrated with an intercontinental

ballistic missile (ICBM) test launch on October 31.

These developments

pose far-reaching challenges to U.S. national security. The United States no

longer has the luxury of ignoring nuclear dangers and concentrating on

deterring a single adversary. To address this new reality, the Biden

administration has modified U.S. nuclear-targeting guidance to be able to deter

China and Russia simultaneously. It is also developing new nuclear delivery

systems, platforms, and warheads. But Washington’s efforts to modernize the

aging U.S. nuclear deterrent have been hampered by inadequate industrial base

capacity, materials and labor shortages, and funding gaps. What needs to be

done is clear: the next administration should dispense with undertaking an

extensive review of either the nuclear deterrence policy or the modernization

plans. There is a huge need to just get on with the work of modernization and

fix the problems.

More Adversaries, Less Time

Over the past three

decades, incoming administrations have generally undertaken a Nuclear Posture

Review, a time-consuming process to determine U.S. nuclear policy and strategy

for the next five to ten years. To understand why the new Trump administration

should limit itself to doing a quick update of the Biden guidance rather than a

complete Nuclear Posture Review, it is important to recognize the threat and

how rapidly it has grown. Although Russia got off to a slow start in its

nuclear modernization program, that effort is now largely complete. Russia has

achieved a modern strategic triad of land-based intercontinental missiles,

strategic submarines and their associated missiles, and bombers and their

air-launched cruise missiles. Each element of the updated triad is a

significant improvement over previous capabilities, and some are also

destabilizing to the existing strategic balance: the Russian Sarmat, for

example, a massive missile designed to replace the heavy SS-18 intercontinental

ballistic missile, can carry a large number of nuclear warheads designed to

attack American ICBMs in a first-strike scenario.

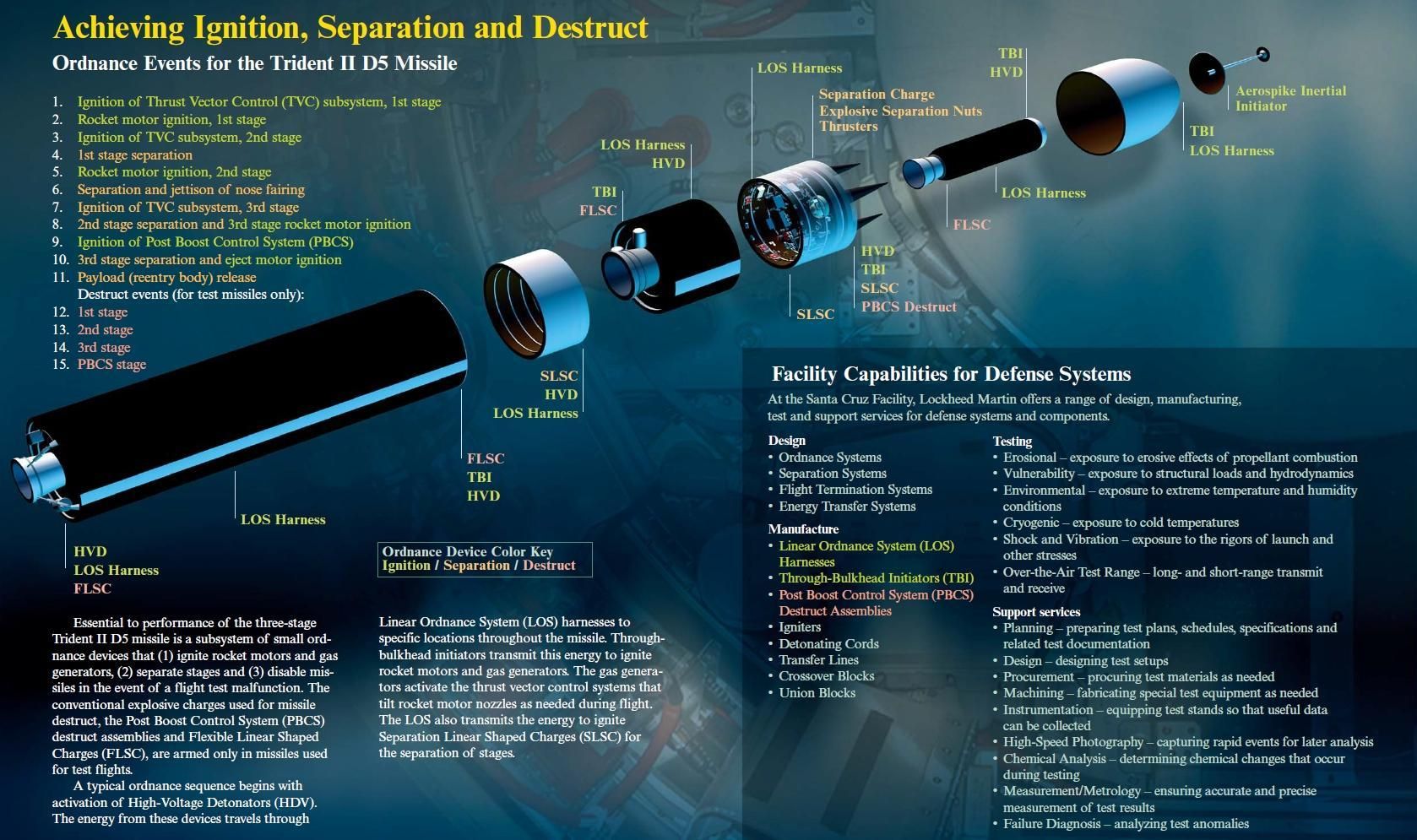

Test-launching a Trident II D5 missile from an

Ohio-class submarine, near the coast of California, March 2018

Several new Russian

nonstrategic systems are deeply disturbing. The Poseidon, an

intercontinental-range nuclear torpedo, for example, is designed to devastate

large coastal areas and render them unfit for habitation for centuries to come.

Of even more concern is Russia’s effort to rebuild all elements of its regional

nuclear forces—short- and medium-range missiles that can be launched from the

ground, sea, or air. These systems are clearly intended to intimidate Moscow’s

neighbors and lend substance to Russia’s new nuclear doctrine, announced by

Putin in September, in which the Kremlin broadened the circumstances in which

it might use nuclear weapons.

China has been

modernizing its nuclear forces even faster. Beginning around 2020, Xi ordered a

massive and rapid expansion of China’s arsenal. The number of strategic nuclear

weapons the country deploys is projected to double from 500 to 1,000 by 2030 and

to reach at least 1,550 by the middle of the next decade. Beijing has already

achieved a capable strategic triad, smaller but similar to that of the United

States and Russia, and it is also expanding and diversifying its regional

nuclear forces. Unlike Russia and the United States, China nominally adheres to

a “no first use” policy. But its nuclear forces have in fact acquired

first-strike and launch-on-warning capabilities.

Chinese intercontinental ballistic missiles in a

military parade, Beijing, October 2019

Although China’s and

Russia’s growing arsenals pose serious challenges, the United States’ nuclear

deterrence policy is fully capable of dealing with them. For more than 45

years, U.S. policy has focused on deterring aggression against vital national

interests and those of U.S. allies by maintaining the ability to target the

assets that potential adversaries value most: themselves and their leadership

cadre, the security infrastructure that keeps them in power, selected elements

of their nuclear and conventional forces, and their war-supporting industries.

In the past, such adversaries might have been leaders of the Soviet Union;

today, they are the regimes of Putin, Xi, and Kim.

Nonetheless, the

growth of Chinese nuclear capabilities will present a new challenge by

introducing a third major nuclear superpower by the mid-2030s. In order to

prepare for the possibility of coordinated or opportunistic aggression by both

Russia and China, U.S. President Joe Biden announced in June modified U.S.

targeting guidance, which, as the National Security Council official Pranay

Vaddi has put it, is designed to “deter Russia, the PRC, and North Korea

simultaneously.” Vaddi went on to say, with reference to U.S. nuclear forces,

that the country “may reach a point in the coming years where an increase in

current deployed numbers is required.”

Left unstated but

highly important is determining the correct size of the U.S. arsenal.

Crucially, the United States’ deployed nuclear force must be sufficiently large

to cover the targets that potential enemies value most, as defined by the most

recent targeting guidance and any subsequent updates. But contrary to what some

commentators have suggested, the United States need not and absolutely should

not increase its nuclear arsenal to match that of Russia’s and China’s

combined. The new guidance, when fully implemented, will provide a strong and

effective deterrent. As a result, the incoming Trump administration should

avoid the years-long guidance development process that new administrations

traditionally undertake—beginning with a Nuclear Posture Review.

Rather than trying to

rewrite the Biden administration’s already updated guidance, the new

administration should focus on those areas in which the United States does have

problems: the slow progress of its own nuclear modernization, the large gaps in

its conventional deterrent, and the significant weaknesses in the U.S. defense

industrial base.

U.S. military officers monitoring a Minuteman III test

launch at Vandenberg Air Force Base, California, March 2015

Three Things at Once

The original creation

of the U.S. nuclear triad was not the result of strategic calculation. The

combination of land-based missiles, submarine-launched missiles, and strategic

bombers arose initially as a result of interservice rivalry in the 1950s. But the

combination of different flight profiles and basing modes proved to be highly

valuable. The first real triad was fielded by the Kennedy administration. Two

decades later, the Reagan administration modernized those forces: it gave the

Minuteman ICBMs new motors and guidance systems, designed a new class of

strategic submarines equipped with new missiles, and provided the aging bomber

force with then stealthy, long-range cruise missiles to ensure their continued

effectiveness. By the turn of the twenty-first century, however, the Reagan-era

triad had become antiquated and should have been replaced. But U.S. strategists

were diverted from this task by a combination of geopolitical assessments—that

Putin, for example, who had come to power only a few years earlier, was not a

threat to the United States or its Western allies and that the overall nuclear

threat had diminished—and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

In 2010, the Obama

administration, as part of its efforts to ratify the New START treaty, a

bilateral arms reduction agreement with Moscow, initiated a program to replace

all three legs of the triad. But the Obama plan immediately ran into

challenges, including budget caps, an inadequate industrial base, workforce

retirements, and the need for parts and materials that no longer existed.

Sadly, all the elements of this program are behind schedule and over budget.

The three legs of the U.S. triad are still safe, secure, and reliable, but they

have been operating well beyond their intended lifespan.

The challenge now is

how to replace the legs of the triad simultaneously—a huge undertaking.

Minuteman III ICBMs were first deployed in the mid-1970s and upgraded in the

1990s. By now, their component parts are obsolete and their lifespan cannot

safely be extended much beyond the mid-2030s. Ohio-class submarines were

designed to operate for around 30 years; 11 out of the 14 boats currently in

commission have served longer than that, and several have been in commission

for more than 35 years. The air-launched cruise missile, deployed in 1980 to

extend the utility of the Eisenhower-era B-52, had a design life of ten years

and is still in service. (It is now scheduled to be retired at the end of this

decade or early next.)

Many of the

replacement weapons themselves have run into development challenges. The

Sentinel ICBM, which was approved in 2014, has incurred a major cost overrun,

in part because it requires the refurbishment of the Minuteman silos and a new

command-and-control system. The navy has recently said that the first

Columbia-class missile submarine—which is designed to replace the Ohio-class

boats—may be delayed by one to two years because of the defense industry’s

inability to produce key components. Although many defense analysts think that

the United States needs at least 200 of the new B-21 bombers to be able to

conduct both conventional and nuclear missions, the program has been

inexplicably limited to just 100 aircraft. The new cruise missile that is intended

for both the B-21 and B-52—a missile known as the long-range stand-off weapon,

or LRSO—has had its near-term funding slashed. This has forced the military to

rely further on an outdated cruise missile that was designed to evade 1980s-era

Soviet air defenses, not the more advanced systems Russia uses today.

An additional

weakness is the U.S. regional nuclear deterrence force. During the Cold War,

the United States deployed several thousand theater-range nuclear systems, but

more than 90 percent of these were eliminated through a series of bilateral

accords with the Soviet Union and Russia in 1991 and 1992. As is well known,

Moscow reneged on its commitments and rebuilt its ground, naval, and air short-

and medium-range nuclear forces. The United States has a small number of

air-delivered bombs in Europe and no dedicated deployed regional nuclear

weapons in the Pacific. Although Washington does not need to replicate the

numbers it maintained during the Cold War, it does need more flexible options.

Congress directed the Biden administration to build and deploy a nuclear-armed

sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N) to provide enhanced deterrence to U.S.

partners in the Pacific and to its NATO allies, but this capability won’t be

available for another decade or more.

Tired Tankers, Withering Warheads

Although nuclear

forces provide the backbone of U.S. deterrence, conventional forces are the

United States’ first line of defense. If conventional forces are sufficiently

strong, they can deter the initial stages of aggression by Russia and/or China,

and the questions of war and nuclear attacks could be avoided. But here, too,

there have been recurring failures.

For example, the air

force does not have enough aerial tankers to support conventional or nuclear

forces in multiple theaters. Tankers are needed to refuel U.S. forces in both

Europe and the Indo-Pacific—a dauntingly large geographic area. But for four long

years, the air force has put off the issue, occasionally offering the prospect

of a “bridge tanker” option but never acting on it. And because the

international situation has deteriorated further over those four years, the air

force has a greater tanker shortfall—perhaps 100 or more—than it did in 2021.

The navy has dropped

from its 2025 budget request a Virginia-class submarine—the newest and most

capable class of nuclear-powered fast attack submarines—because of conflicting

priorities with surface ships and defense industry delays. The United States’ nuclear-powered

attack submarine force is well below what is necessary to provide a

simultaneous deterrent in both the North Atlantic and the Pacific. Similarly,

the navy’s mismanagement of ship and submarine overhauls has resulted in

years-long delays on badly needed assets. In the same vein, the navy has

complained for over a decade about Russia’s and China’s growing ability to

block others from entering the waters and air space around their periphery. Yet

it treats the best countermeasure—the hypersonic conventional prompt strike

(CPS) missile—as if it is a luxury. Deployment will occur in dribs and drabs

until the middle of the next decade, even though U.S. combatant commanders in

the European and Asia-Pacific theaters are deeply worried about the next three

to four years.

The B-21 Raider, a strategic bomber developed for the

U.S. Air Force, in Palmdale, California, December 2022

Apart from effective

delivery systems, the United States needs to update the nuclear warheads or

bombs that these systems will carry. In the hopeful period after the end of the

Cold War, China, Russia, and the United States, along with all other nuclear weapons

states, signed the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, a multilateral

agreement to stop all explosive nuclear testing. Although the treaty has never

entered into force, the United States has unilaterally adhered to it. As a

result, the country has had to rely on means other than testing in the

monitoring and development of its nuclear stockpile.

When Washington

signed the treaty, it assigned the Department of Energy to establish a program

to scientifically replicate the data that had been previously gathered from

nuclear testing. This program was extraordinarily successful, and the DOE and

the National Nuclear Security Administration have been able to maintain all

remaining warheads in the U.S. nuclear stockpile through life-extension

programs. But now that most of the warheads have either been or are in the

process of being “life extended,” the NNSA must start to design and develop new

nuclear weapons using these same scientific and computational capabilities,

rather than testing.

This will not be

easy. For one thing, the NNSA must relearn design and manufacturing skills and

requalify existing vendors or find new ones. The bigger challenge, however, is

the NNSA production complex. Unlike the NNSA’s science and computational facilities,

the production complex was largely ignored after the Cold War. NNSA is now

struggling to keep obsolete facilities—a few of which date back to the

Manhattan Project or the early days of the Cold War—functioning until they can

be replaced. This massive construction program is also behind schedule and over

budget. There are many reasons for this, including a lack of skilled workers,

design difficulties, and a diminished industrial base, but generally this work

hasn’t been done in 25 years.

As NNSA shifts from

extending the lifespan of existing warheads to making new ones, the production

complex must relearn how to produce key components or materials or find

substitutes and adapt to modern manufacturing techniques. A new round of budget

caps is further constraining the ability of the complex to modernize.

Get it Done

The primary task

facing the Departments of Defense and Energy right now is getting the new

systems built. The new secretary of defense should draw on the lessons of

Reagan’s defense secretary, Caspar Weinberger, who, during the triad

modernization effort of that era, instituted a series of ongoing reviews of all

three programs. For each program, he required the service secretary, the

service chief, and the program manager to report to him every three months on

program status and on efforts to fix any apparent problems.

The service

secretariats have now proved themselves unreliable and untrustworthy: the new

defense secretary should institute Weinberger-style reviews for the Sentinel

ICBM, the Columbia-class submarine, the B-21 bomber, and probably the LRSO

missile programs. The administrator of the National Nuclear Security

Administration, in conjunction with the secretary of energy, should adopt a

similar process to review the NNSA warhead and construction programs.

The secretary of

defense should institute similar reviews for redressing the tanker shortfall

and the delays in Virginia-class submarine production, along with speeding the

development of the CPS missile and the nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise

missile (SLCM-N). These reviews should seek to enable the two major submarine

producers to increase their output as quickly as possible; accelerate the

deployment of CPS missiles, even through stopgap

nontraditional means such as box launchers on large deck ships; initiate an

immediate program to buy new tankers and fill in gaps in the inventory with

leased tankers until enough new aircraft can be built and deployed; and assure

and accelerate the development of the SLCM-N missile.

Given the possibility

of further delays in these efforts, the new administration should provide

sufficient funding to ensure that existing deployed systems—such as the U.S.

nuclear command, control, and communications network, known as NC3, and the

Ohio-class submarines—can continue to operate past their currently planned

retirement dates and that the life-extension programs for current stocks of

warheads are fully funded.

The United States

will have to keep the old systems safe, secure, and reliable to continue to

deter Russia and China. This will become especially crucial after the New START

treaty expires in February 2026. To hedge against the premature retirement of

an existing platform, the incoming administration should be prepared to begin a

major effort to assure resilience and flexibility. It can do this by adding

warheads to existing Minuteman and Trident 2 missiles; restoring, on Ohio-class

submarines, the submarine-launched ballistic missile tubes that were disabled

according to New START and loading Trident 2 missiles in them; procuring

additional Trident 2 missile motors to allow a sufficient pool of test assets

to exist after reloading the empty tubes; and “re-converting” to a nuclear role

those B-52 bombers that were rendered incapable of launching a nuclear weapon

under New START.

Additionally, the

administration should seek to increase strategic deterrent forces beyond the

current budget horizon. It can do this by planning to deploy Sentinel missiles

in a multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV) configuration,

allowing a single missile to attack several targets at once; increasing the

planned number of deployed long-range stand-off weapons; increasing the planned

number of B-21 bombers and aerial tankers an expanded force would require;

increasing the planned production of Columbia-class submarines and their

Trident ballistic missile systems; and accelerating the development and

deployment of the D5LE2 replacement missile.

Washington should

assess the feasibility of fielding some portion of the future ICBM force in a

road-mobile configuration—an approach that would involve mobile launchers that

could be quickly relocated. It should also speed efforts to develop new countermeasures

to respond to the advanced missile defenses of U.S. adversaries and plan for a

portion of the future bomber fleet to be on a continuous alert status.

Finally, the Trump

administration should get serious about rebuilding the U.S. defense industrial

base. It should rapidly review the Biden administration’s 2023 Defense

Industrial Strategy and October 2024 expanded guidance, updating and revising

both as necessary. It should promulgate this guidance and immediately convene a

summit with the secretary of defense and the CEOs of major defense firms (and

perhaps their major sub-tier suppliers, as well) to expand the base and make it

more agile as rapidly as possible.

The incoming

administration will undoubtedly face calls to hold a full-blown Nuclear Posture

Review to examine and validate existing policy. Every administration since 1952

has reviewed its predecessor’s nuclear (and other) defense policies, but it has

only been since 1994 that this has involved a large interagency review. These

full-scale reviews have on occasion been statutorily mandated, but all have

been hugely time-consuming and on balance have taken a year or more to

complete.

Given that the

current guidance—with the recent Biden changes—is fully up to date and more

than adequate to guide the command’s planning, there is no need for the Trump

administration to conduct a massive review. A quick senior-level review within

the administration should suffice. This not only will preserve a

well-functioning policy but also will avoid a waste of senior-level focus and

get the much-needed updated plans in place sooner. The new administration will

surely face significant new challenges to U.S. nuclear deterrence. The United

States and its allies simply do not have the luxury of waiting another three

years for these challenges to be met.

For updates click hompage here