By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Repeated financial

crises, rising inequality, renewed protectionism, the COVID-19 pandemic, and

growing reliance on economic sanctions have ended the post-Cold

War era of hyper-globalization. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine may have

revitalized NATO, but it has also deepened the divide between East and West and

North and South. Meanwhile, shifting domestic priorities in many countries and

increasingly competitive geopolitics have halted the drive for greater economic

integration and blocked collective efforts to address looming global dangers.

The international

order that will emerge from these developments is impossible to predict. It is

easy to imagine a less prosperous and more dangerous world characterized by an

increasingly hostile the United States and

China, a remilitarized Europe, inward-oriented regional economic blocs, a

digital realm divided along geopolitical lines, and the growing weaponization

of economic relations for strategic ends.

But one can also envision

a more benign order in which the United States, China,

and other world powers compete in some areas, cooperate in others,

and observe new and more flexible rules of the road designed to preserve the

main elements of an open world economy and prevent armed conflict while

allowing countries greater leeway to address urgent economic and social

priorities at home. More optimistically, one can even imagine a world in which

the leading powers actively work together to limit the effects of climate change,

improve global health, reduce the threat of weapons of mass destruction, and

jointly manage regional crises.

Establishing such a

new and more benign order is not as hard as it might sound. Drawing on the

efforts of the U.S.-China Trade Policy Working Group—a forum convened in 2019

by New York University legal scholar Jeffrey S. Lehman, Chinese economist Yang

Yao, and one of us (Dani Rodrik) to map out a more constructive approach to

bilateral ties—we propose a simple, four-part framework to guide relations

among major powers. This framework presupposes only minimal agreement on core

principles—at least at first—and acknowledges that there will be enduring

disagreements about how many issues should be addressed. Rather than imposing a

detailed set of prescriptive rules (as the World Trade Organization and other

international regimes do), this framework would function as a “meta-regime”: a

device for guiding a process through which rival states or even adversaries

could seek agreement or accommodation on a host of issues. When they do not

agree, as will often be the case, adopting the framework can still enhance

communication among them, clarify why they disagree, and offer them

incentives to avoid inflicting harm on others, even as they seek to protect

their interests.

Crucially, this

framework could be put in place by the United States, China, and other major powers, as they deal with various contentious

issues, including climate change and global security. As has already been shown

on several occasions, the approach could provide what a single-minded focus on

the great-power competition cannot: a way for rival powers and even adversaries

to find common ground to maintain the physical conditions necessary for human

existence, advance economic prosperity, and minimize the risks of major war,

while preserving their security.

Incentives to compete

are ever present in a world lacking a central authority, and the most potent

powers will no doubt continue to eye one another warily. If any significant

powers make economic and geopolitical dominance their overriding goal, the

prospects for a more benign global order are slim. But systemic pressures to

compete still leave considerable room for human agency. Political leaders can

still decide whether to embrace the logic of all-out rivalry or strive for

something better. Human beings cannot suspend the force of gravity, but they

eventually learned to overcome its effects and took to the skies. The

conditions that encourage states to compete cannot be eliminated, but political

leaders can still take action to mitigate them if they wish.

Fewer rules, better behavior

According to many accounts,

the international order that emerged in the 1990s has increasingly been eroded

by the dynamics of great-power competition. Nonetheless, the deterioration of

the rules-based order need not result in great-power conflict. Although the

United States and China both prioritize security, that goal does not render

irrelevant the national and international goals that both share. Moreover, a

country that invested all its resources in military capabilities and neglected

other objectives—such as an equitable and prosperous economy or the climate

transition—would not be secure in the long run, even if it started as a global

power. The problem is not the need for security in an uncertain world, but how

that goal is pursued and the tradeoffs states face when balancing security and

other vital goals.

It is increasingly

clear that the existing, Western-oriented approach is no

longer adequate to address the many forces governing international power

relations. The future world order must accommodate non-Western powers and

tolerate greater diversity in national institutional arrangements and

practices. Western policy preferences will prevail less, the quest for

harmonization across economies that defined the era of hyper-globalization will

be attenuated, and each country will have to be granted greater leeway in

managing its economy, society, and political system. International institutions

such as the World Trade Organization and the International Monetary Fund must

adapt to that reality. Rather than more conflict, however, these pressures

could lead to a new and more stable order. Just as it is possible for

significant powers to achieve national security without seeking global primacy,

it is possible and even advantageous for countries to reap the benefits of

economic interdependence within looser, more permissive international

rules.

In our framework,

major global powers need not agree in advance on the detailed rules that would

govern their interactions. Instead, as we have outlined in a working paper for

the Harvard Kennedy School, they would agree only on an underlying approach to

their relations in which all actions and issues would be grouped into four

general categories: those that are prohibited, those in which mutual

adjustments by two or more states could benefit all parties, those undertaken

by a single state, and those that require multilateral involvement. This

four-part approach does not assume that rival powers trust one another at the

outset or even agree on which actions or issues belong in which category.

However, successfully addressing disagreements within this framework would

increase trust and reduce the possibility of conflict.

The first

category—prohibited actions—would draw on widely accepted norms by the United

States, China, and other major powers. At a

minimum, these might include commitments embodied in the UN Charter (such as

the ban on acquiring territory by conquest), violations of diplomatic immunity,

the use of torture, or armed attacks on another country’s ships or aircraft.

States might also agree to forgo “beggar thy neighbor” economic policies in

which domestic benefits come at the direct expense of harm done to others: the

exercise of monopoly power in international trade, for instance, and deliberate

currency manipulation. States will violate these prohibitions frequently, and

governments will sometimes disagree on whether a particular action violates

an established norm. But by recognizing this general category, they would

acknowledge that there are boundaries to acceptable actions and that crossing

them has consequences.

The second category

includes actions in which states stand to benefit by altering their behavior in

exchange for similar concessions by others. Prominent examples include

bilateral trade accords and arms control agreements. Through mutual policy

adjustments, rivals can reach agreements that benefit each other economically

or eliminate specific areas of vulnerability, thereby making both countries

more prosperous and secure and allowing them to shift defense spending to

different needs. In theory, one could imagine a significant

power agreeing to limit specific military deployments or activities—such

as reconnaissance operations near the other’s territory or harmful

cyber-activities that could adversely affect the other’s digital

infrastructure—in exchange for equivalent limitations by the other side.

When two states

cannot reach a mutually beneficial bargain, the framework offers a third

category, in which either side is free to take independent actions to advance

specific national goals, consistent with the principle of sovereignty but

subject to any previously agreed-on prohibitions. Countries frequently take

independent economic actions because of differing national priorities. For

example, all states set their highway speed limits and education policies

according to domestic preferences, even though higher speed limits can raise

the price of oil on world markets and improving educational standards can

affect international competition in skill-intensive sectors. On national

security matters, meaningful agreements among adversaries or geopolitical

rivals artoughrd to reach, and independent action is

the norm. Even so, the framework dictates that such actions must be well

calibrated: to prevent tit-for-tat, escalatory steps that risk a destabilizing

military buildup or even open conflict, remedies should be proportional to

the security threat at hand and not designed to damage or punish a rival.

Of course, what one

country views as a well-calibrated response may be perceived as a provocation

by an opponent. Worse estimates of a rival’s long-term intentions may make it

hard to respond in a measured fashion. Such pressures are already apparent in

the growing military competition between the United States and China. Yet both

have powerful incentives to limit their independent actions and objectives.

Given that both are vast countries with large populations, considerable wealth,

and sizable nuclear arsenals, neither can entertain any realistic hope of

conquering the other or compelling it to change its political system. Mutual

coexistence is the only realistic possibility. All-out efforts by either side

to gain strategic superiority would simply divert resources from

critical social needs, forgo potential gains from cooperation, and raise

the risk of a highly destructive war.

The fourth and final

category concerns issues in which effective action requires the involvement of

multiple states. Climate change and COVID-19 are obvious examples: in each

case, the lack of an effective multilateral agreement has encouraged many

states to free-ride, resulting in excessive carbon emissions in the former and

inadequate global access to vaccines in the latter. In the security domain,

multilateral agreements such as the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty have

limited the spread of nuclear weapons. Because any world order ultimately rests

on norms, rules, and institutions that determine how most states act most of

the time, multilateral participation on many key issues will remain

indispensable.

Viewed as a whole,

our framework enables rival powers to move beyond the simple dichotomy of “friend

or foe.” Undoubtedly, states sometimes adopt policies to weaken a rival or gain

an enduring advantage. Our approach would not make this feature of

international politics disappear entirely for the major powers and many others.

Nonetheless, by framing their relations around these four categories, rival

powers would be encouraged to explain their actions and clarify their motives

to each other, thereby rendering many disputes less malign. Equally important,

the framework increases the odds that cooperation would grow over time. A

conversation structured along the lines we propose enables the parties to

separate potential zones of cooperation from the more divisive or contentious

issues, establish reputations, develop a degree of trust, and better understand

the preferences and motives of their partners and rivals—as can be seen

when considering concrete, real-world situations.

Strategic transparency

Several recent

conflicts demonstrate the advantages of our approach. Consider the U.S.-Chinese

competition over 5G wireless technology. The emergence of the Chinese company

Huawei as a dominant force in global 5G networks has concerned the U.S. and

European policymakers not only because of the commercial consequences but also

because of the national security implications: Huawei is believed to have close

ties to the Chinese security establishment. But the hard-line

response by the United States—which has sought to cripple Huawei’s

international activities and pressure U.S. telecommunications operators not to

do business with the company—has only ratcheted tensions. By contrast, our

framework, although it would allow Western countries considerable latitude in

limiting the activities of Chinese firms such as Huawei within their own

countries, mainly on national security grounds, would also restrict attempts by

the United States and its allies to undermine Chinese industries through

deliberate and poorly justified international restrictions.

The promise of a

better-calibrated strategy for dealing with the Huawei conflict has already

been shown. In contrast to the actions taken by Washington, the British

government entered an arrangement with Huawei in which the company’s products

in the British telecommunications market undergo an annual security evaluation.

The evaluations are conducted by the Huawei Cyber Security Evaluation Centre,

whose governing board includes a Huawei representative and senior officials

from the British government and the United Kingdom’s telecommunications sector.

If the annual evaluation finds areas of concern, officials must make them

public and state their rationale. Thus, the 2019 HCSEC report found that

Huawei’s software and cybersecurity system posed risks to British operators and

would require significant adjustments to address those risks. In July 2020, the

United Kingdom decided to ban Huawei from its 5G network.

Ultimately, the

decision may have had less to do with the hcsec

report than direct U.S. pressure. However, this example still illustrates

the possibilities of a more transparent and less contentious approach. The

technical reasoning on which a national security determination was made could

be seen and evaluated by all parties, including domestic firms with a

commercial stake in Huawei’s investments, the Chinese government, and Huawei

itself. This feature alone can help build trust as each party develops a fuller

understanding of the motives and actions of the others. Transparency can also

make it more difficult for home governments to invoke national security

concerns as a cover for purely protectionist commercial considerations. And it

may facilitate reaching mutually beneficial bargains in the long run.

Nonetheless, most

actions in the high-tech sector are likely to end up in our third category, in

which states take unilateral measures to advance or protect their interests.

Here, our framework requires the responses to be proportionate to actual or

potential harms rather than a means to gain strategic advantage. The Trump

administration violated this principle by barring U.S. corporations from

exporting microchips and other components to Huawei and its suppliers,

regardless of where they operated or the purposes for which their products were

used. Instead of seeking to protect the United States from espionage or

cyberattack, the clear intention was to deliver a fatal blow to Huawei by

starving it of essential inputs. Moreover, the U.S. campaign has had severe

economic repercussions for other countries. Many low-income countries in Africa

have benefited from Huawei’s relatively inexpensive equipment. Since U.S.

policy has important implications for these countries, Washington should

have engaged in a multilateral process that acknowledged the costs that

cracking down on Huawei would inflict on others. This approach would have

conserved global goodwill to U.S. national security at little cost.

Acting, not escalating

Our framework also

suggests how the troubled relationship between the United States and Iran might

be improved to benefit both parties. For starters, the present level of

suspicion could be reduced if both sides publicly committed not to attempt to

overthrow the other and to refrain from acts of terrorism or sabotage on the

other’s territory. An agreement should be easy to reach, at least in principle,

given that the UN Charter already prohibits such actions. Iran also lacks the

capacity to attack the United States directly, and past U.S. efforts to

undermine the Islamic Republic have repeatedly failed.

Turkish President

Tayyip Erdogan meeting with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy in Lviv,

August 2022

Although short-lived,

the 2015 nuclear deal showed how even hardened adversaries could be brought

together on a contentious issue through mutually beneficial adjustments. The

deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), was a perfect

illustration of this negotiated approach: China, France, Germany, Russia, the

United Kingdom, the United States, and the European Union agreed to lift

economic sanctions linked to Iran’s nuclear program, and Iran agreed to reduce

its stockpile of enriched uranium and dismantle thousands of nuclear

centrifuges, substantially lengthening the time it would take Tehran to produce

enough weapons-grade uranium to build a bomb.

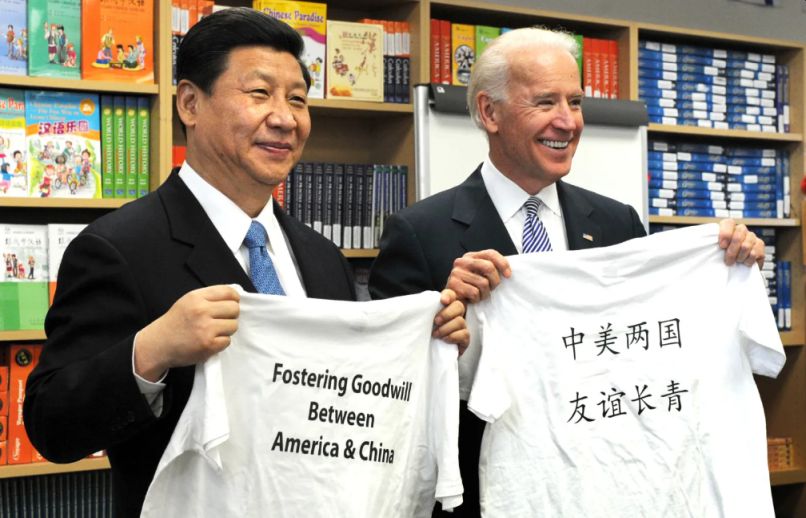

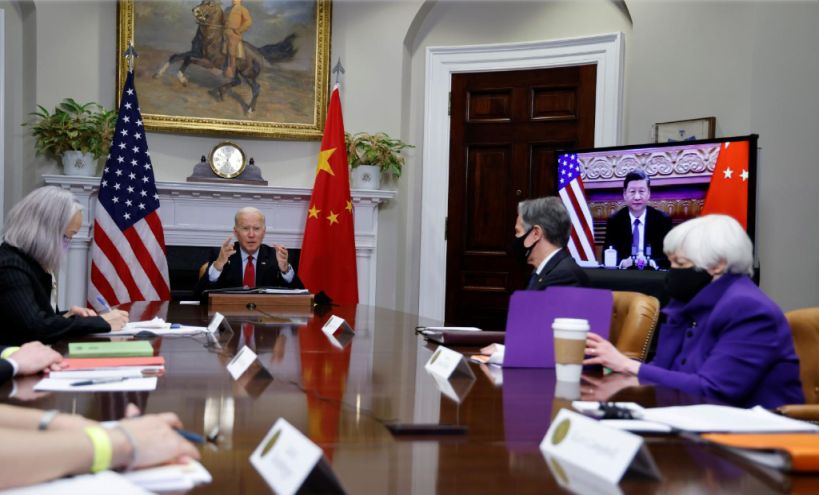

U.S. Presiden Joe Biden speaking virtually with Chinese

leader Xi Jinping in Washington, November 2021

The JCPOA’s

proponents hoped the agreement would lead to a broader discussion of other

areas of dispute: subsequent negotiations, for example, could have constrained

Iran’s ballistic missile programs and other regional activities in exchange for

further sanctions relief or the restoration of diplomatic relations. At a

minimum, talks along these lines would have allowed both sides to explain and

justify their positions and given each a clearer understanding of the other’s interests,

redlines, and sensitivities. Unfortunately, these possibilities were foreclosed

when the Trump administration unilaterally abandoned the JCPOA in March 2018.

Skeptics might claim

that the fate of the JCPOA reveals the limits of this approach. They might

argue that had the agreement been in both sides’ interests, it would still be

in effect today. But the shortsighted U.S. withdrawal left both sides worse

off. Iran is much closer to producing a bomb than it was when the JCPOA was in

force, the two countries are if anything, even more, suspicious of each other,

and the risk of war is arguably higher. Even an objectively beneficial

agreement will not endure if one or both parties do not understand its merits.

Given the current

state of relations, the United States and Iran will continue to act

independently to protect their interests. Still, there is reason to believe

that both sides understand the principle that unilateral actions should be

proportional. When the United States left the JCPOA in 2018, Iran did not

respond by immediately restarting its entire nuclear program. Instead, it

adhered to the original agreement for months afterward, hoping that the United

States would reconsider or that the other signatories would fulfill its terms.

When this did not occur, Iran left the agreement in an incremental and visibly

reversible fashion, signaling its willingness to return to full compliance if

the United States did so. Iran’s reaction to the Trump administration’s

“maximum pressure” campaign was also measured. For example, the U.S.

assassination of the high-ranking Iranian general Qasem

Soleimani by a drone strike did not lead Iran to escalate; on the contrary, its

response was limited to nonlethal missile attacks on bases

housing U.S. forces

in Iraq. The United States had occasionally shown restraint as well, as when

the Trump administration chose not to retaliate when Iran downed a U.S.

reconnaissance drone in June 2019. Despite deep animosity, up to now, both

sides have recognized the risks of escalation and the need to calibrate their

independent actions carefully.

From aggression to mediation

There is no question

that Russia’s war in Ukraine has

darkened the prospects for constructing a more benign world order. Moscow’s

aggression was a clear violation of the UN Charter, and some Russian

troops appear guilty of wartime atrocities. These actions demonstrate that even

well-established norms against conquest or other war crimes do not always

prevent them. Yet the international response to the invasion shows that trampling

on such norms can have powerful consequences.

The war also

highlights the importance of our second category—negotiation and mutual

adjustments—and what can happen when states do not fully exploit this option.

Western officials engaged with their Russian counterparts on several occasions

before Russia’s invasion. Still, they did not address Moscow’s stated

concern—namely, the threat it perceived from Western efforts to bring Ukraine

into NATO and the EU. For its part, Russia made far-reaching demands that

seemed to offer little room for negotiation. Instead of exploring a genuine

compromise on this issue—such as a formal pledge by Kyiv and its Western allies

that Ukraine would remain a neutral state combined with a de-escalation by

Russia and renewed negotiations over the status of the territories Russia

seized in 2014—both sides hardened their existing positions. On 24 February,

2022, Russia launched its illegal invasion.

The failure to

negotiate a compromise via mutual negotiation left Russia, Ukraine, and the

Western powers in our framework’s third category: independent action. Russia

unilaterally invaded Ukraine, and the United States and NATO responded by

imposing unprecedented sanctions on Russia and sending billions of dollars of

arms and support to Ukraine. In keeping with our approach, however, even amid

this fierce conflict, each side has thus far sought to avoid escalation. At the

outset, the Biden administration declared that it would not send U.S. troops to

fight in Ukraine or impose a no-fly zone; Russia refrained from conducting

widespread cyberattacks, expanding the war beyond Ukrainian territory, and

using weapons of mass destruction. As the war has continued, however, this

sense of restraint has begun to break down, with U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd

Austin asserting that the United States has sought to weaken Russia over the

long term and Russian officials hinting about the use of nuclear weapons and

indicating that their war aims may be expanding.

Unilateral action in

Ukraine has also caused significant harm to third parties. By dramatically

raising the cost of energy, Western sanctions on Russia have dealt a severe

blow to the economies of low- and middle-income countries, many already

devastated by the COVID-19 pandemic. And Russian blockades of grain

shipments out of Ukraine have exacerbated a growing world food crisis. Because

the war has affected many other countries, ending the fighting and lifting

sanctions will likely require multilateral engagement. Turkey has already

helped mediate an agreement to allow the resumption of Ukrainian grain exports.

States that rely on these exports will no doubt seek arrangements that make

future disruptions less likely. If a Ukrainian pledge to remain neutral is part

of the deal, it must be endorsed by the United States and other NATO members. Kyiv will undoubtedly want assurances from its

Western backers and other interested third parties or perhaps an endorsement in

the form of a un Security.

Great powers, greater understanding

The war in Ukraine is

a sobering reminder that a framework such as ours cannot produce a more benign

world order by itself. It cannot prevent states from blundering into a costly

conflict or missing opportunities to improve relations. But using these broad

categories to guide great-power ties, instead of trying to resurrect a

U.S.-dominated liberal order or impose new global governance norms from above,

has many advantages. In part, because the requirements for adhering to it are

so minimal, the framework can reveal whether rival powers are seriously

committed to creating a more benign order. A state that rejects our approach

from the start or whose actions within it show that its expressed commitments

are bogus would incur severe reputational costs and risk provoking greater

opposition over time. By contrast, states that embrace the framework and

implement its simple principles in good faith would be regarded by others more

favorably and would likely retain greater international support.

Perhaps nowhere are

the potential benefits of our framework more apparent than in U.S.-Chinese

relations. Until now, the United States has failed to

articulate a China policy aimed at safeguarding vital U.S. security and

economic interests that do not also aim at restoring U.S. primacy by

undermining the Chinese economy. Far from accommodating China within a

multipolar system of flexible rules, the current approach seeks to contain

China, reduce its relative power, and narrow its strategic options. When the

United States convenes a club of democracies aimed openly against China, it

should not be surprising that Chinese President Xi Jinping cozies up to Russian

President Vladimir Putin.

This is not the only

way forward, however. China and the United States have emphasized the need to

cooperate in key areas even as they compete in others, and our approach

provides a practical template for doing just that. It directs the two rivals to

look for points of agreement and actions that both recognize should be

proscribed; it encourages them to seek mutually beneficial compromises, and it reminds

them to keep their independent actions within reasonable limits. By committing

to our framework, the United States and China would be signaling a shared

desire to limit areas of contention and avoid a spiral of ever-growing

animosity and suspicion. In addition to cooperating on climate change, pandemic

preparedness, and other shared interests and refraining from overt attempts to

undermine each other’s domestic prosperity or political legitimacy, Washington

and Beijing could pursue a variety of arms control, crisis management, and

risk-reduction measures through a process of negotiation and adjustment.

On the thorny issue of Taiwan, the United States

should continue the deliberately ambiguous policy it has followed since the

1972 Shanghai Communiqué—aiding Taiwanese defense efforts and condemning

attempts by Beijing at forced reunification while opposing unilateral Taiwanese

independence. Abandoning this policy in favor of more immediate recognition of

Taiwan risks provoking a war in which no one would benefit. Our

flexible approach would not help if China decides to invade Taiwan for purely

internal reasons—but it would make it less likely that Beijing would take this

fateful step in response to its security concerns.

Members of the

Chinese People’s Liberation Army in Tiananmen Square, Beijing, September 2021

Managing U.S.-Chinese

security competition has a multilateral dimension, as well. Although Asian

countries are concerned by China’s rising power and want U.S.

protection, they do not want to choose between Washington and Beijing. Efforts

to strengthen the U.S. position in Asia are bound to be alarming to China.

Still, the magnitude of its concerns and the intensity of its response are not

predetermined, and minimizing them (to the extent possible) is in everyone’s

interest. As Washington strives to shore up its Asian alliances, it should also

support regional efforts to reduce tensions in Asia and encourage its allies to

avoid unnecessary quarrels with China or one another. U.S.-promoted regional

trade deals, such as the newly launched Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for

Prosperity, should focus on maximizing economic benefits rather than trying to

isolate and exclude China.

Although we have

emphasized state-to-state relations in this discussion, our approach could be

equally productive for nonstate actors, civil society organizations, academics,

thought leaders, and anyone with a stake in a particular issue. It encourages

global community members to go beyond the stark antinomy of conflict versus

cooperation and focus on practical questions: What actions should be prohibited

outright? What compromises or adjustments would be feasible and mutually

beneficial? When is independent action expected and legitimate, and how can

well-calibrated actions be distinguished from excessive actions? And when will

preferred outcomes require multilateral agreements to ensure that third parties

are not adversely affected by the agreements or actions undertaken by others?

Such conversations will not produce immediate or total consensus. Still, more

structured exchanges on these questions could clarify tradeoffs, elicit

clearer explanations or justifications for competing positions, and increase

the odds of reaching mutually beneficial outcomes.

It is possible—some

would say likely—that mutual suspicion, incompetent leadership, ignorance, or

sheer bad luck will combine to produce a future world order that is

significantly poorer and substantially more dangerous than the present one. But

such an outcome is not inevitable. The tools are available if political leaders

and the countries they represent genuinely wish to construct a more prosperous

and secure world.

For updates click hompage here