By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

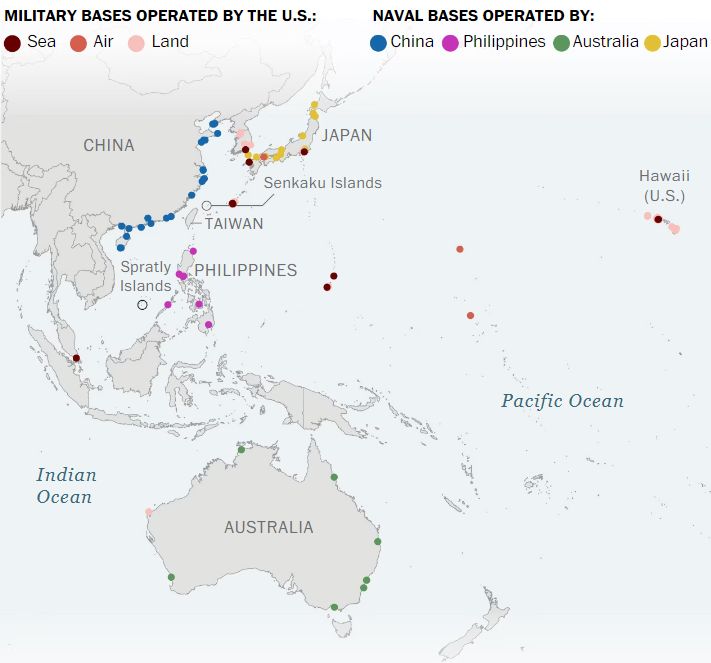

Allies Are Beefing Up Defenses In The Pacific

The provocative actions

taken by China, North Korea, and Russia have prompted the United States and its

closest allies in the Indo-Pacific to ramp up military capabilities and deepen

their cooperation. “They’re bolstering their defenses, they’re looking to

strengthen their alliances and partnerships with the United States in

particular, and they’re reaching out to each other,” said Ely Ratner, assistant

secretary of defense for Indo-Pacific security affairs. “All of these things

are happening at once.”

The trend, the Biden

administration says, reflects efforts to create a free and prosperous

Indo-Pacific through the steady forging of partnerships — moving toward what it

calls a “latticework” of mutually reinforcing coalitions.

Much of the progress

is becoming evident only recently.

In December, Japan

announced it would massively hike its defense budget and buy U.S.-made Tomahawk

cruise missiles. The Philippines this month said it would allow U.S. troops to

access four additional military sites in the country. And Australia is expected

in the coming weeks to unveil a path forward to acquire nuclear-powered

submarines with the help of the United States and Britain — a plan, officials

said, that is likely to include rotational deployment of U.S. submarines in

Australia to help the navy there train its crews.

At the same time,

some countries are wary of being seen as aligned too closely with the United

States. For instance, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia focus on avoiding

crossfire in the great-power competition and say they do not wish to be forced

to choose between China and the United States.

India, an important

partner in the Biden administration’s Indo-Pacific strategy, has been willing

to cooperate with the United States in military exercises, most recently in

defense technology. But, keen to preserve its policy of strategic autonomy, it

has avoided becoming part of any multilateral security arrangement or joining

any coalition to pressure Russia or China.

Meanwhile, Russia’s

invasion of Ukraine and China’s eye-watering military growth — already boasting

the world’s largest navy and last year conducting more ballistic missile tests

than the rest of the world combined — has stoked regional fears that a Chinese

invasion of Taiwan is a possibility. Though it might not be imminent, some top

U.S. generals warn that American troops must be ready.

Indeed, the United

States itself, Aquilino said, needs to improve its force posture in the region.

“Everything needs to go

faster,” he said. Everyone needs “a sense of urgency because that’s what it’s

going to take to prevent a conflict.”

Admiral John C.

Aquilino, left, commander of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, looks at videos of

Chinese structures and buildings on board a U.S. P-8A Poseidon reconnaissance

plane flying over the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea on 20 March 2022

A New Forward-Leaning Security Projection

In the commander’s foyer

sits a 3D model of an artificial island built by the Chinese atop a reef in the South China Sea. It’s outfitted with a

3,000-meter runway and fighter jet hangars. For scale, a replica of the

Pentagon fits in the island’s harbor, dwarfed by the 680-acre island

constructed several years ago by the Chinese military.

It’s a reminder of

how quickly China has expanded its military reach into the region, rattling

neighbors such as Taiwan, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

Chinese structures and buildings on the man-made Fiery

Cross Reef in the disputed Spratly Islands in the South China Sea.

It’s a reminder of

how quickly China has expanded its military reach into the region, rattling

neighbors such as Taiwan, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

“It’s having an

effect,” Aquilino said. “Nations are operating in ways they haven’t operated

before.”

He pointed to a

six-nation exercise in the Philippine Sea in October 2021 that came together

with such speed and stealth that it had no name. It featured the U.S. carriers

Carl Vinson and Ronald Reagan and the British carrier Queen Elizabeth, a

Japanese carrier and a Dutch destroyer, synchronizing with aircraft and undersea

maneuvers and space and cyberspace operations.

European and NATO

countries, too, are concerned about the growing threats in the Indo-Pacific.

Last summer, Aquilino’s

command completed the largest-ever maritime exercise off the Hawaiian Islands

and Southern California with 26 nations, several dozen ships, three submarines,

170 aircraft, and more than 25,000 personnel. Participants included Chile,

Indonesia, Tonga, France, Germany, India, and Japan.

Japan, in particular,

has come a long way in a short time in acknowledging the regional threat China

and North Korea pose. In December, it abandoned a half-century of restrained

defense spending and committed to nearly doubling its defense budget over five

years — making it the world’s third largest. It also announced it would develop

a counterstrike missile capability. Japanese officials, for domestic political

purposes, downplay the shift as defensive.

In this handout

photo, members of the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force 5th Surface-to-Surface

Missile regiment stand by for inspection during the Rim of the Pacific 2022

exercise on 16 July 16, 2022, in Hawaii.

But they are candid

about the urgency.

“The reason we have

to put up arms is because of the increasingly severe and complex security challenges

in the region, which are posed by North Korea, China, and Russia,” Noriyuki Shikata, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s Cabinet press

secretary, said in an interview. “Given the security landscape in Asia, we must

respond by building up our defenses. So we need to improve our deterrence

capabilities.”

Along with the

Tomahawk cruise missiles, which can reach mainland China, Japan has agreed to

let the U.S. Marine Corps revamp a unit in Okinawa so that they can rapidly

disperse to fight in remote islands closer to Taiwan. This new Marine littoral

regiment will be equipped with anti-ship missiles that could, experts say, be

fired at Chinese ships in a Taiwan contingency.

Tokyo also intends to

integrate its self-defense forces into U.S. military exercises in Australia, a

deepening of the trilateral security arrangement that officials say is

emblematic of a growing latticework.

For instance, North

Korea’s provocations have drawn long-standing rivals South Korea and Japan

closer, and an emerging partnership links the United States, the Philippines,

and Japan. Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. visited Tokyo this month

and signed several agreements, including on defense cooperation.

South Korean Marine

Corps soldiers at a military checkpoint on Baengnyeong

Island, South Korea, on March 30, 2021. Since the fighting ended in the Korean

War nearly seven decades ago, Baengnyeong has been a

key location for U.S. allies in Seoul to spy on North Korea.

The last year has

been “an incredible inflection point” for countries like Japan, said Rahm

Emanuel, the U.S. ambassador in Tokyo. “Japan has gone from a mindset of

alliance protection to alliance projection. That is the new paradigm for the

United States, Japan, and the region.”

Australia is expected

in the coming weeks to unveil a plan with the United States and Britain to help

it develop nuclear-powered submarines. When the subs are built and operating,

which officials say will likely be sometime in the 2030s, the initiative,

referred to as AUKUS, will be one of the region's

most significant force modernization efforts.

“The progress has

been substantial,” said one U.S. official, who spoke anonymously because of the

matter’s sensitivity. “They’re moving closer to a major announcement. Not only

will this involve the mechanics and finances around building a submarine, but

it will also have substantial elements of joint crew training, facilities

maintenance, and other areas of integration that promise to bring the three

navies ever closer together.”

President Biden,

joined by Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison and British Prime Minister

Boris Johnson, announced on 15 Sept. a new Indo-Pacific alliance.

Deploying U.S.

nuclear submarines in Australia — even on a rotational basis — would be

significant, experts say, as a base in the Indian Ocean would be outside the

range of most Chinese missiles. “But the main reason it would be significant is

it would show the Australians are serious about getting ready to deploy their

nuclear-powered subs,” said Michael J. Green, chief executive of the United

States Studies Center at the University of Sydney and a White House Asia aide

in the George W. Bush administration.

The AUKUS deal has

angered the Chinese, who view it as a deliberate provocation and accuse the

United States and partners of trying to contain China through an “Anglo-Saxon

clique.” China’s Foreign Ministry has attacked the arrangement as potentially

undermining the international nuclear nonproliferation regime.

Australia notes that

the Non-Proliferation Treaty does not bar a nonnuclear weapon state from

acquiring naval nuclear propulsion technology. The Australian submarines would

not carry nuclear weapons. A foreign affairs department spokesperson said AUKUS

“will be fully consistent” with the treaty.

Seeking To Stay Out Of The Fray

Not all countries are

as eager to trumpet their deeper defense cooperation ties with the United

States — or China, for that matter.

In Thailand, a

long-standing ally in Southeast Asia, defense officials said that the United

States appeared to be paying more attention to the region as China ramps up its

efforts to expand its influence. But Lt. Gen. Kongcheep

Tantravanich, a spokesman for the Defense Ministry,

said Thailand did not want to be “manipulated” by either country.

“We have to maintain

our status as neutral,” Kongcheep said from Bangkok.

Thailand last year

said it would purchase a significant amount of military equipment from the

United States and begin a program — the first of its kind between the two

countries — to share information on defense technologies. The program will also

naturally lead to the exchange of military personnel, said Panitan

Wattanayagorn, chief of the Thai government’s

security affairs committee. “We don’t lose anything” with these agreements, Panitan said, adding that he does not think they stop

Bangkok from continuing to strengthen its relationship with Beijing.

Like Thailand, the

South Koreans don’t want to get caught in the crossfire between China and the United

States, said Markus Garlauskas, director of the

Atlantic Council’s Indo-Pacific Security Initiative and a former national

intelligence officer for North Korea in the U.S. intelligence community. He

noted a Korean saying: “When whales fight, a shrimp’s back gets broken.”

Home to more than

28,000 U.S. troops, South Korea in recent years has shown a willingness to

align itself more clearly with the United States than it did in previous years,

analysts say. In December, for instance, South Korea issued an Indo-Pacific

strategy that didn’t mention China, echoing similar strategies that the United

States, Japan, and Australia issued. Opinion polls show that public sentiment

has turned against China in recent years, as Koreans felt “bullied” by Chinese

economic retaliation in 2017 after installing a U.S. antimissile

battery in response to threats from North Korea, Garlauskas

said.

Seoul views

increasing cooperation with the United States and Japan, in both exercises and

communication, as a key part of assuring the public about South Korea’s

security, a senior South Korean official said. Its Defense Ministry announced

it would hold a one-day tabletop nuclear exercise at the Pentagon this week.

India, which will

host this year’s Group of 20 meeting of the world’s leading economies and

aspires to great-power status in its own right, has come to view China as its

principal adversary following several years of violent border clashes with

Chinese troops that have caused fatalities on both sides. That has pushed New

Delhi closer to Washington.

President Biden,

center, Secretary of State Antony Blinken, left, India's Minister of Defense

Rajnath Singh, right, and Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin take part in a

virtual meeting with India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Just last month,

Washington and Delhi held the inaugural meeting of a strategic partnership

announced in May by Biden and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi that

encourages their domestic industries to develop artificial intelligence, jet

engines, and semiconductors jointly. And last year, in a first, a U.S. Navy

ship arrived in India for repairs — a significant step for the Indian

shipbuilding industry and the bilateral defense relationship. This cooperation

comes against the intensification of U.S.-India military exercises over the

last several years.

“India, for its

reasons, has now decided to become part of a broader set of balancing

coalitions against China in the Indo-Pacific,” said Ashley Tellis,

an India expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

But while India is

happy to receive technical assistance and conduct joint military exercises,

both of which help it develop its capabilities, “they do not want to convey to

anyone, including the Chinese, that there is somehow a U.S.-India alliance

against China,” Tellis added.

Biden administration

officials often hold the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or “the Quad,” as an example of their Indo-Pacific strategy

taking hold. Formed by Japan, Australia, India, and the United States as an ad

hoc effort to coordinate humanitarian relief during the devastating 2004 Indian

Ocean tsunami, it languished for years, then was revived during the Trump

administration, and has since evolved to serve as a geopolitical counterweight

to China. Beijing has accused the four countries of seeking to form an “Asian

NATO,” though the partnership lacks a mutual defense commitment.

And while Japan and

Australia are crucial to any U.S.-led regional effort to deter China from

invading Taiwan, India has few direct equities there.

“They wish the

Taiwanese well, but they’re not going to come to their rescue,” Tellis said.

A key variable is Seoul.

“Whether South Korea supports Taiwan or remains neutral could play a huge role

in whether or not China chooses to pursue aggression against Taiwan,” Garlauskas said, noting the United States has military

forces stationed on the Korean Peninsula that could reach the Chinese mainland.

When it comes to the

rest of the allies and partners, the difference between countries such as Japan

and Australia on the one hand and Thailand and Indonesia on the other is that

the former feels a “very clear sense of direct threat” from China, said

Christopher B. Johnstone, a former White House director for East Asia who is

now with the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Japan has seen a

decade of Chinese aggression over the Senkaku islands, administered by Tokyo

but over which Beijing lays claim. In August, as part of military drills in

response to Pelosi’s visit, China fired ballistic missiles over Taiwan that

landed in waters off Japan, in its exclusive economic zone. Australia has been

on the receiving end of China’s efforts to weaponize economic ties, slapping

draconian tariffs on coal, wine, and other goods after Australia’s prime

minister early in the coronavirus pandemic called for a global inquiry into the

virus’s origins.

Putting Quills On The Porcupine

In recent weeks,

Australian officials say that Canberra and Beijing have tried to stabilize

their relationship. However, that will not undermine Australia's deepening

security partnerships with the United States, Britain, and other allies.

“[F]or Australia, the

sense of China as a bully that seeks to intimidate its neighbors — that became

much more visceral over the last few years,” Johnstone said.

Meanwhile, with much

of Southeast Asia and Oceania, “none of them are choosing China,” Green said.

“They’re just trying to stay out of the fray as best they can.”

Officials say that

improving the U.S. military’s capabilities in the region increasingly depends

on cooperation from allies and partners. In particular, China’s growing arsenal

of precision-guided missiles threatens the U.S. Air Force in the region.

Deployed And Dispersed

Underneath two U.S.

Air Force B-1B strategic bombers, right, South Korean Air Force F-35 fighter

jets, bottom, and U.S. Air Force F-22 stealth fighter jets flying over the

Yellow Sea between China and the Korean Peninsula during a joint air drill.

“If you have all of

your aircraft in a few huge bases, and they shut the airfield down, then you

can’t get airborne,” said Gen. Kenneth Wilsbach, U.S.

Pacific Air Forces commander.

The service has been

shifting from large, centralized bases to networks of smaller airfields

dispersed around the region at sites hosted by partner nations, including

Japan, the Philippines, and Micronesia.

Under the “agile combat

employment” strategy, the Air Force operates temporarily out of an airfield in

Palau, shuttling personnel and aircraft as needed. It has been lengthening

runways and positioning munitions, food, and water at regional sites.

In a recent

interview, David Panuelo, Micronesia’s president,

said that the United States was upgrading an airfield and seaport on his

country’s island of Yap, intending to prevent war with China, not starting one.

“We do that through a deterrent,” he said.

Panuelo said he believed Washington’s efforts in the region

were beginning to have an effect. “Pacific nations are looking at the alignment

of their relationships,” he said, citing a failed Chinese effort last year to

reach a regional security pact and other recent setbacks for Beijing.

The service has been

shifting from large, centralized bases to networks of smaller airfields

dispersed around the region at sites hosted by partner nations, including

Japan, the Philippines, and Micronesia.

Under the “agile

combat employment” strategy, the Air Force operates temporarily out of an

airfield in Palau, shuttling personnel and aircraft as needed. It has been

lengthening runways and positioning munitions, food, and water at regional

sites.

David Panuelo, Micronesia’s president, said in a recent interview

that the United States was upgrading an airfield and seaport on his country’s

island of Yap to prevent war with China, not starting one. “We do that through

a deterrent,” he said.

Panuelo said he believed Washington’s efforts in the region

were beginning to have an effect. “Pacific nations are looking at the alignment

of their relationships,” he said, citing a failed Chinese effort last year to

reach a regional security pact and other recent setbacks for Beijing.

The U.S. military is

also seeking to gain access to more locations in the region.

This month Manila

announced it had granted the United States access to four new Philippine

military sites, bringing the total to nine in the archipelagic nation.

Officials did not specify what types of bases — Army or Navy, for instance —

and said announcements of exact sites awaited negotiations with local

officials. However, officials said at least two of the four are expected to be

on the island of Luzon, whose northernmost tip is just a couple hundred miles

from Taiwan.

China’s aggressive

response to Pelosi’s visit last summer, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and

Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s securing of a third term have sparked a realization

in Taiwan that the self-governing island needs to be better prepared to defend

itself in the event of a conflict.

Tourists look on as a

Chinese military helicopter flies past Pingtan Island

in Fujian province, one of mainland China's closest points to Taiwan.

Taiwanese President

Tsai Ing-wen has extended compulsory military service from four months to one

year. But that isn’t enough, argue experts, who, when speaking of Taiwan’s

defense, say that it needs to resemble a porcupine bristling with quills —

boasting a variety of nimble weapons systems that would make it dangerous to

would-be attackers.

But the Taiwanese

military is “still stuck on the idea of fighter jets, warships, and tanks,”

said retired Adm. Lee Hsi-ming, Taiwan’s top military

leader from 2017 to 2019.

Like U.S. military officials

and defense experts, Lee wants to see Taiwan focus more on less costly, more

mobile weaponry — such as anti-ship cruise missiles and naval mines — that can

nonetheless inflict pain on an adversary and more readily survive Chinese

attacks.

“Suddenly asking them

to spend less on tanks and more on Javelins or Stingers — it’s not an easy

change to make,” Lee said, referring to the shoulder-fired missiles that proved

critical in helping Ukraine stop Russian forces from taking Kyiv.

Lee argued that Taiwan

would benefit from a demonstration of intent from Washington about its

readiness to defend Taiwan in a conflict. President Biden has publicly affirmed

on at least four occasions that the United States would come to Taiwan’s

defense. However, Washington’s official policy remains one of “strategic

ambiguity” — designed to keep China guessing about whether an island invasion

would see the U.S. military enter the fray.

Harpoon A-84

anti-ship missiles and AIM-120 and AIM-9 air-to-air missiles are prepared for

weapons-loading drills in front of an F-16V fighter jet at the Hualien Airbase

in Taiwan.

“You need to show

China that preparations are taking place,” Lee said. “It can’t just be empty

talk.”

U.S. commanders

agree.

'The stronger Taiwan

is all the way around, the higher the deterrent value that is, and the greater

the chance we have that China will decide that now is not the time” to invade,

said Wilsbach.

CIA Director William

J. Burns said this month that his agency had intelligence indicating that Xi

has directed the People’s Liberation Army to be capable of a successful

military invasion of Taiwan by 2027, when the PLA will mark its centennial.

However, he hastened to add that it doesn’t mean China’s president will order

one.

Still, Lee said

that’s a valuable milestone against which Taiwan should pace its defensive

preparations. “[T]he intricate complexity of cross-strait relations means that

for Taiwan, it’s not so important to pay close attention to 2024, 2025, or

2027. The most important thing is determining how soon we can be ready.”

The backlogged U.S.

defense production system is also a major challenge; experts noted, now

stretched even tighter by the war in

Ukraine. “Look at how

we have been buying F-16s for five or six years, but we still don’t have them,”

Lee pointed out. “What can we do to deter China and defend ourselves

immediately? That’s where we need to be investing.”

U.S. Defense Secretary

Lloyd Austin, left, shakes hands with South Korean Defense Minister Lee

Jong-sup after a news conference following their meeting in Seoul on 31 Jan.

U.S. capabilities

need to advance, too, Aquilino said. One of the things he’s pushing for is

advanced long-range missiles that can be launched from air or sea to take out

an adversary’s ships in the region.

Back in his office, overlooking

the military base that was the site of a catastrophic surprise attack more than

eight decades ago for which the U.S. military was not prepared, Aquilino is

determined that the United States not witness another Pearl Harbor.

Much has changed since

then. The U.S. military holds more than 100 exercises with countries in the

Indo-Pacific each year. Aquilino commands 375,000 troops and civilians in the

region. And, after China, the top five economies in the region are all

democracies.

But Beijing, developing

advanced hypersonic missile capabilities and on course to have 1,500 nuclear

weapons in the next decade, is threatening to destabilize what Aquilino calls

the “rules-based order” that has enabled nations “over the past eight decades

to be secure, sovereign, prosperous.''

Defense Secretary

Lloyd Austin has given him two missions, he said. The first: is to do

everything in his power to avoid a war in the Pacific. “We spend a lot of time

working to prevent that conflict,” he noted.

The second mission,

if it comes to war, is to fight and win. “If deterrence fails,” Aquilino said,

“Indo-Pacom is prepared to do that mission as well.”

For updates click hompage here