By Eric Vandenbroeck and

co-workers

US President Wilson and the Asian Monroe

Doctrine

In part one, we gave

a general overview of the 1919 or "Wilsonian moment,” a notion that

extends before and after that calendar year, in part two, issues

like the Asian Monroe Doctrine, how relations between China and Japan from the

1890s onward transformed the region from the hierarchy of time to the hierarchy

of space, Leninist and Wilsonian Internationalism, western and Eastern

Sovereignty, and the crucial March First and May Fourth movements, in part three the

important Chinese factions beyond 1919 and the need for China to create a new

Nation-State and how Japan, in turn, sought to expand into Asia through liberal

imperialism and then sought to consolidate its empire through liberal

internationalism. And in part four the various arrangements between the US and

Japan including The Kellogg–Briand Pact or Pact in 1928 and The Treaty for the

Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament of 1930. This whereby American

policy toward Japan until shortly before the Pearl Harbor attack was not

the product of a rational, value-maximizing decisional process. Rather, it

constituted the cumulative, aggregate outcome of several bargaining games

which would enable them to carry out their preferred Pacific strategy.

In analyzing the Manchurian crisis and its connection to the

winding road to World War II it is tempting to fall into the conceptual trap of

simple dichotomies. A standard dichotomy for what happened in Manchuria is

that a small cabal of "militarists" hijacked power from a helpless

civilian government in Tokyo and ran amok for the next fifteen years. There are

many reasons for the tenacity of this historical interpretation, stemming from

facile contemporary assumptions, the imperatives of America's postwar

occupation of Japan, as well as influential popular histories like John

Toland’s The Rising Sim. The preponderance of evidence, however,

makes clear that a broad coalition of Japanese elites, including Emperor

Hirohito. members of the Privy Council and House of Peers, statesmen,

intellectuals, and military officials, were responsible for Japan's subsequent

retreat from liberal internationalism and the empire’s expansionism in Asia

over die next fifteen years (1931-1945).

From the beginning,

as noted, the Kwantung Army had the tacit endorsement of the Army General

Staffs operations and intelligence divisions. It also enjoyed support from

“renovationist" politicians and intellectuals. Renovationists (sometimes

called “reformists") carried with them a mash-up of resentment and indignation,

particularly against Anglo-American liberalism and the international status

quo.1

What bound this wide

swath of Japanese elites together on the Manchurian issue, from the crown to

statesmen, diplomats, scholars, and business leaders, and ultimately the mass

of Japanese society, were three layers of “special" rationale: special

rights, special interests, and special responsibilities. "Special rights”

comprised a legalistic defense, based on "rights of possession" from

previous wars and treaties. The transfer of leasehold rights in southern

Manchuria that Japan won in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) can hardly be

overstated. Japan mobilized more than one million troops during the war;

81.455 of them lost their lives. This considerable sacrifice cultivated a keen

sense of regional entitlement. Indeed, Manchuria became regarded as hallowed

ground, an impression seared into the consciousness of a generation of

Japanese who came into positions of political, military, and intellectual

authority m the 1930s. Adding to this sense of entitlement was that the empire

had sunk an enormous amount of capital into the leased territory. The South

Manchurian Railway became Japan’s biggest firm, with interests in rail freight,

shipping, coal mining, soybean production, and tourism.2 There remained as

well a psychological hangover from the Twenty-One Demands of 1915, a belief,

embedded into the fabric of historical truth, that China had freely accepted

the demands. And now, China was going back on its word, violating treaties, and

abusing Japan.

“Special

interests." on the other hand, referred to national security interests

that derived from “nature and geography." Japan's proximity to China, went

this “realist” argument, gave Japan unique decision-making prerogatives on the

continent. In modem diplomatic parlance, this meant that China and its

frontiers were a vital interest, economically and strategically. During the

Manchurian crisis. Japanese began to describe Northeast China as Japan’s

“lifeline.” There was much talk about the need for raw materials and outlets

for surplus trade and population. However inflated these claims, the important

point is that Japanese officials and commentators at the time became convinced

of their veracity.

A third factor is

that Japanese officials as we have seen became animated by a more chauvinistic

strain of Pan-Asianist thinking, which posited that Japan had a “special

responsibility” to rescue Asia from the West. Japanese grievance against the

West thus was melded with superiority toward the East. Japan was now

self-consciously cast as an exceptional nation, preordained to bring about the

regeneration of Asia. Japan, after all, alone among Asian nations, had modernized,

fought off unequal treaties, and stunned the world by defeating Tsarist Russia.

This paternalistic strand of Pan-Asianism recalled the spirit of imperialism's

“civilizing mission” from the late nineteenth century, in which a caretaker

nation had a moral obligation, the “white man's burden," to bring order

and progress to allegedly less-enlightened peoples In fact, during the

Manchurian crisis, the American-based Japanese journalist K. K. Kawa kami

claimed that Japan’s leadership in Manchuria was “one of the most significant

developments in the century, a great experiment in the reorganization,

regeneration, and rejuvenation of an ancient nation long wallowing in chaos and

maladministration....For the first time in history, a non-white race has

undertaken to cany the white man’s burden."3

Such expansive

purpose required a profound sense of national uniqueness. In the 1930s. as

scholars of Japan have made clear, strong currents of exceptional ism flowed

through Japan's body politic from a multiplicity of influential tributaries,

with some headwaters reaching back to the early twentieth century A

nationalist literary movement, the Japan Romantic School, for example, exalted

the unique traits and importance of Japanese civilization. Particularly

industrious was a group of philosophers from Kyoto Imperial University, led by

Professor Nishida Kitaro, who extolled the uniqueness of the Japanese family

state. Other significant sources included eminent academies who filled think

tanks. Nichiren Budding millennialists, ultranationalists

such as Kita Dcki, Kanji

Ishiwara, and Pan-Asianist ideologues like Shūmei

Ōkawa.4 That the Manchurian crisis acted as a powerful

ideological catalyst and coagulant in Japanese flunking can be deduced by

comparing Kawakami's spirited piece above on Japan's mission with a commentary

he wrote ten years prior, during the Washington Conference:

All the Powers ...

have bound themselves by agreements or resolutions not to return to the old

practice of spheres of influence or special interests [in China)....This

change is no shadowy thing. It is as definite as it is real. Twenty years ago

the Powers were talking only what they could take from China. Today they are

talking about what they can give her. Certainly that indicates a vast moral

progress.5

Thus, what was once

the “vast moral progress” of liberal self-denial now required Japan's

civilizing intervention.

Eventually,

Pan-Asianist-inspired "special responsibilities” developed into the

principal justification for Japanese expansionism in the decade following the

Manchurian crisis. The imperative of a Japanese rescue mission in Asia

resonated with the imaginings of an alternative world order, unfettered by the

liberal language of the Nine-Power Treaty and the Kellogg Pact.

Colonial dominoes fall

The war itself

quickly unfolded in favor of Japan’s regionalist ambitions. While Japanese

forces attacked Pearl Harbor, they also overran Guam. Hong Kong, and Wake

Island. Within a few months, colonial dominoes had fallen throughout Southeast

Asia, producing unforgettable images of white overlords capitulating to their

Japanese conquerors. In February 1942, more than eighty thousand British troops

surrendered in Singapore, a military defeat

considered, to this day, as one of Britain's worst. In March, the Dutch surrendered

Indonesia: in May, the Americans did the same in the Philippines A significant

turning point, however, came just as quickly. In June 1942, Japan’s gains at

Pearl Harbor evaporated at the Battle of Midway. Thereafter, the conflict

turned into a slow and tortuous slaughter across the vast expanse of Pacific

atolls and islands Whatever the private convictions among the young Japanese

and American combatants who faced one another in unfathomable existential

moments, hovering over every battlefield and landing zone were far-reaching and

competing ideas of world order.

At home and abroad,

Japan’s campaign into the South Seas glistened with the revisionist promises of

liberation and coprosperity. In January 1942, Premier Tojo told the Diet that

Japan had embarked on “truly an unprecedentedly grand undertaking . . . [to]

establish everlasting peace in Greater East Asia based on a new conception,

which will mark a new epoch in the annals of mankind, and proceed to construct

a new world order along with our allies and friendly powers in Europe."

More comprehensively, at a summer conference in Kyoto in 1942, a prominent

group of Japanese intellectuals gathered under the slogan “Overcoming the

Modern" and critiqued the “corrupting” influences of an Americanized

modernity. As one scholar has noted, the symposium's participants believed “all

the ills that had poisoned Japan were found in Americanism,” which included its

values, culture, and commodities.6 The claim of liberating fellow Asians

and overcoming the corrupt tenets of Anglo-Americanism was an intoxicating

ideological brew carrying great moral purpose. To this end, the Japanese

government reoriented the cultural programs of the Kokusai Buuka

Shiukokai toward the South Seas to help spread the

Pan-Asianist scripture of Japan’s alleged holy war.

Throughout occupied

Southeast Asia, the KBS disseminated publications, films, and Japanese language

textbooks to promote the empire's prestige and leadership. The conscious

intertwining between political and cultural motives can be seen in the words of

KBS Chairman Matsuzo Nagai who asserted

that the promotion of Japanese culture would make the peoples of Asia ‘ grasp

the true intention of Japanese actions" and "understand the significance

of our holy war " The KBS’s soft power programs thus were politically

malleable, the theme of Japanese cultural importance could be tailored lo

American cosmopolitans or Asian nationalists. What did not change was tire

irrefutable message of regional primacy.7 Tokyo's propaganda challenge

also remained the same: to square its promise of liberation with coercive rule.

Japan’s leaders were

not unaware of a gap between theory and practice. This was made clear in

November 1943 just as the empire's fortunes in the Pacific were becoming

increasingly bleak. In an attempt to reinvigorate the alleged altruism of

Japan’s motives, the Tojo government invited leading statesmen from around Asia

to attend the so-called Greater East Asia Conference in Tokyo, under the

banner of the utopian strand of Asian solidarity. The puppet heads of the

Manchukuo and Nanjing regimes joined leaders from Burma, the Philippines.

India, and Thailand. Although die Tokyo conference accomplished little of

substance other than to issue an anti-Anglo- American “joint declaration,” it

nonetheless indulged the language of liberation and independence and portended

postwar decolonization, even if paradoxically wedded still to Japanese

autarky, As Fujitani Takasbi has argued, even if we

acknowledge such discourse as propaganda, “it is difficult to deny the

unintended or unavoidable consequences” of officially declaring disavowals of

racism and promises of greater equality.8

Under far more

auspicious circumstances, in July 1944, seven months after the Tokyo

conference, more than seven hundred delegates, including economists,

financiers, politicians, and industrialists, from forty-four

Allied nations trekked to northern New Hampshire to attend a virtual

renaissance party for liberal internationalism. The Bretton Woods Conference,

as it was called, breathed institutional life into that Wilsonian offspring,

the Atlantic Charter, with the goal of stabilizing a liberal postwar economic

order. It was an acknowledgment of the close and profoundly consequential

relationship inbetween national and international

economies. To secure the global monetary system, the system of exchange rates

and international payments that allows nations to transact with each other, the

conference created the International Monetary Fund. To provide developmental

financing, the World Bank was born. As in Wilson’s time, the overall goal of

these programs was to encourage global peace and prosperity through so-called

orderly processes.9

One month later, at

the Dumbarton Oaks Conference in Washington. DC, the Allies began laying the

foundation for the United Nations, with hopes of making amends for the nearly

stillborn League of Nations. Of note, according to Fujitani, similar to the

effects of Japan's strategic wartime disavowals of racism. America's

universalizing wartime rhetoric of freedom and selfdetermination

not only "made it increasingly necessary to disavow- racist

discrimination” but to "demonstrate the sincerity of this denunciation

through concrete plans.” Beyond influencing the loosening of US immigration

restrictions (the United States began accepting Chinese immigrants again in

1943 and Japanese immigrants in 1952). wartime rhetoric played a key role in

the ensuing global era of decolonization. This is not to gloss over persistent

hypocrisies and complexities. As Mark Mazower lias noted, how docs one square

the United Nations’ stated ideals with the fact that a committed

segregationist. South Africa's Jan Smuts, helped draft the institution's lofty

preamble? Or, more palpably, cases of violent resistance to independence

movements by the colonizing powers and their allies.10

Self-interest, to be

sure, mingled with idealism. Every institution established at Bretton Woods

and Dumbarton Oaks, for better or worse, earned the ubiquitous imprint of

American leadership and liberal principles. After slugging it out against

fierce ideological foes in both Europe and the Pacific, the American mindset

could accurately be described as be sure not to make the same mistake

twice. Henry Luce's 1941 commentary “The American Century” represented an

early and forceful expression of this evolving worldview. calling for vigorous

American leadership. "In 1919,” wrote Luce, "we had a golden

opportunity ... to assume the leadership of the world.... We did not understand

that opportunity. Wilson mishandled it. We rejected it. We bungled it in the

1920s and in the confusion of the 1930s we killed it.” It must not happen

again, he warned Americans. “America is responsible.” Luce said, "for the

world-environment in which she lives.” He concluded with missionary zeal,

claiming “all of us are called... to create the first great American Century

”11 In some ways, despite different desired ends. Luce’s expansive call to

action mirrored Japanese rhetoric. Just as Japan viewed its struggle in Asia as

holy war. Luce characterized the conflict as a holy war for a free-market,

democratic order. The main ideological difference, albeit a significant one,

was that of an exclusive regionalism versus a more open internationalism.

The moment of America's

ideological redemption arrived in 1945. In May. Germany surrendered to Allied

forces. In the Pacific, the brutal islandhopping

campaign came to a halt on June 22 after the Battle of Okinawa. American

commanders subsequently scheduled an invasion of the Japanese home islands to

start in November. In the meantime, a methodical firebombing campaign

incinerated large parts of sixty-plus Japanese cites. And then, in early

August, with bewildering suddenness, came three shocks in four days. On August 6

an atomic bomb killed more than eighty thousand Japanese civilians in

Hiroshima. Two days later the Soviet Union declared war on Japan. And on August

9. another A-bomb leveled the city of Nagasaki. (The sparing of Kyoto and its

cultural treasures from atomic destruction on account of Secretary of War

Stimson's personal intervention raises questions about the possible influence

of KBS programs.)12

Following Nagasaki,

and facing Total annihilation. Emperor Hirohito finally accepted Allied terms

for surrender. The forty-four-year-old emperor spoke to the nation for the

first time on August 15. Filled with regret and sadness, the recorded address

announced Japan’s surrender and encouraged the Japanese people “to endure the

unendurable" But ideology made an appearance as well. The emperor reminded

his subjects of the noble Asianist goals for which they allegedly fought.

"We declared war on America and Britain." asserted Hirohito.

"out of our sincere desire to insure Japan's self-preservation and the

stabilization of East Asia, it being far from our thought either to infringe

upon the sovereignty of other nations or to embark upon territorial aggrandizement.”

He also extended the nation's “deepest sense of regret to our allied nations of

East Asia, who have consistently cooperated with tire Empire toward the

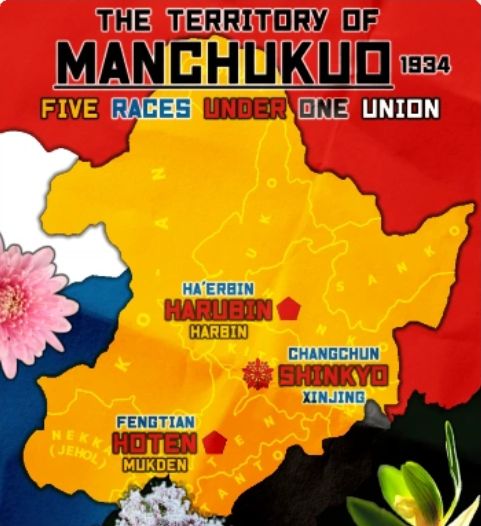

emancipation of East Asia."13 Thus, despite the deaths of an

estimated twelve million Chinese from Japanese aggression, the myth of

coprosperity, that Manchukuo and the Wang regime were not puppet states, but

allied partners fighting side by side in a good fight for a new order in Asia,

was duly perpetrated.

In the United States,

President Harry S. Truman also described the end of the war in ideological

terms, stating: “This is the end of the grandiose schemes of the dictators to

enslave the peoples of the world, destroy their civilization, and institute a new

era of darkness and degradation. This day is a new beginning in the history of

freedom on this earth.”14 The uplifting words momentarily papered over aspects

of the Asia-Pacific War perhaps more properly defined in moral gradations

rather than absolutes. In the coming decades. Americans would be compelled to

grapple morally with their government’s decision to drop two nuclear bombs on

civilian populations, with the second bomb coming just three days after the

first, as well as the illegal internment of nearly 120.000 innocent Japanese

Americans. Bui for the immediate future, the thousands of American troops and

bureaucrats pouring into Japan, led by General Douglas MacArthur, seemed to

affirm Truman's declaration.

The American

occupation of Japan lasted nearly seven years (1945-1952).15 Despite

considerable Japanese agency, the occupation amounted to an unprecedented

undertaking in nation-building and ideological overhaul. Under the banner of

“demilitarization and democratization,” the American authorities instituted

land reform, education reform, and a free press and. of greatest significance,

drafted Japan’s postwar constitution. The liberal charter completely

transformed Japan's polity. It turned the emperor into a depoliticized symbol

of the slate, abolished the House of Peers and hereditary aristocracy, mandated

party cabinets, and gave women the franchise. Initially it also disbanded

Japan's military. The pacifist Article 9 inserted into the constitution

essentially incorporated the principles of the Kellogg Pact by prohibiting

Japan from using armed forces in an offensive war.16

At the same time, in

a move that had far-reaching effects. MacArthur chose not to prosecute Emperor

Hirohito for war responsibility; instead, he used the exalted crown to drive a

wedge between the nation as a whole and a culpable military clique. In other

words, the occupation resurrected the 1930s “dualism” of Ambassador Grew and

other so-called Japan Hands and superimposed it onto the occupation. On a

practical level, this helped stabilize the occupation, but it also cut the rope

to the anchor of self-reflection regarding war responsibility. In the postwar

years, the Japanese people drifted in a sea of moral ambiguity, leading to the

prevalence of the Grew-tinted “dark valley” thesis. According to this

interpretation, a small cabal of militarists defied the emperor and civilian

government and took ail innocent nation down the path of militarist min. Grew

himself publicized his convictions just before the end of the war. saying

Japan's military had established a “dictatorship of tenor" over the

people. Such views created lasting stereotypes about Japan's polity for years

to come As KBS official Aoki Setsuichi claimed two

decades after the war. “The military blatantly pressured us ... to conduct

cultural projects to camouflage military intent.” As a result of tills revived

thesis, after the war, former officials such as Shigeinitsu

Maniom, Yoshida Sbigeru,

and Kishi Nobusuke quietly traded in their imperialist clothes for

internationalist garb. Shigeinitsu subsequently

became involved in the United Nations, and Yoshida saved as premier for nearly

seven years.17

The Allies' Tokyo War

Crimes Tribunal (1946-1948), meanwhile, set out to make a sweeping case against

Japanese militarists. In the process, it inadvertently opened up a Pandora’s

box to ideological sparring by charging the defendants with "crimes

against peace” (conspiring to wage war), a novel category in international law

established by the Nuremberg Tribunal (1945-1946). This allowed the accused to

recycle the specious claim that Japan had only sought to liberate Asian peoples

from Western oppression, and that, from

Manchuria to Pearl Harbor, the empire had acted in selfdefense

against Anglo-American encirclement, As a result, though the Allies disarmed

Japan's military and effectively extirpated the militarist ethos in society,

the tribunal earned the cynical moniker a “victors’ justice.”18 Such a

confused and conflicted legacy of the war, not unlike the sordid Lost Cause

legacy of the .American Civil War, has prompted a parade of postwar Japanese

politicians to make controversial visits to the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo as

well as tone-deaf remarks about Japan’s wartime responsibility. The result has

been repeated protests among Chinese and Koreans, not to mention protests by

Japanese pacifists.19

In the cultural

realm, the organization that had helped spread the idea of benevolent Japanese

leadership in the occupied territories, the Kokusai Rimka

Shiukokai, was left in institutional limbo

immediately after the war. One American scholar at the time eviscerated the KBS

as an apologist for military aggression, thus challenging the society's claims

of institutional autonomy and innocent dedication to the arts. Occupation

officials, meanwhile, tended to associate traditional Japanese cnlnire with feudalistic practices and thus initially

suppressed it. The specter of communism in Asia, however, eventually

stimulated a reappraisal and subsequent reversal of some occupation policies,

tire so-called reverse course, which included reconstituting the KBS.

Accordingly, in 1949, many former KBS officials, including Dan Ino, Maeda

Tamon, Kabayarua Aisuke,

and Prince Takamatsu, reprised their roles as cultural ambassadors, but this

time under a mission statement that heralded “a fresh stan with new ideals and

goals”, as part of "the rebirth of Japan as a cultural stale along

democratic lines.”20 And so began one aspect of Japan’s postwar transformation

from enemy to ally.

The first cultural

projects sprouted from myriad institutions, including die KBS, Japan’s Ministry

of Foreign Affairs and Cultural Properties Protection Commission, the US State

Department, and Japan societies. John D. Rockefeller III. a cultural advisor

for Washington’s 1951 Peace Mission to Japan, was a key figure. In the ensuing

years Rockefeller, along with Kabayama and Matsumoto Shigeharu

(a top Domei official and confidant of Premier

Konoe), poured energies into establishing a nonprofit, nonpolitical center for

intellectual cooperation and cross-cultural exchange in the heart of Tokyo.

This was the International House of Japan (I-Honse), which officially opened in

1955. Rockefeller also helped organize a major touring exhibition of Japanese

cultural treasures in 1953. which bore a sinking resemblance to the 1936 MFA

show. American critics uniformly praised the show, seen by nearly five hundred

thousand people. Japan’s ambassador to the United States, Araki Eikichi,

meanwhile, invoked standard "soft power” assumptions, saying the

exhibition "served to draw even closer the bonds of culture and

friendship which exists between our countries.” A 1955 publication sponsored by

the Council on Foreign Relations. Japanese and Americans: A Century of

Cultural Relations, echoed Araki’s sentiments, maintaining that “cultural

interchange can lay the groundwork for solution of mutual problems.”

Conclusion part six

One of the reasons

why we started this what will be an eight part investigation is among others

because as we have seen, the US is concerned that China is flirting with the

idea of seizing control of Taiwan as President Xi Jinping becomes more willing

to take risks to boost his legacy. A good reason why we covered the

Asia-Pacific War 1941 till September 1945. Like Japan due to earlier agreements

with China felt justified to take Manchuria, not unlike China perceives Taiwan

and a large part of the Pacific (the South China Sea) as their own. Similarly

when Japan saw itself in a special role as mediator between the West

(“Euro-America”) and the East (“Asia”) in order to “harmonize” or “blend” the

two civilizations and demanded that Japan lead Asia in this anti-Western

enterprise there are parallels with what Asim Doğan in his extensive new book

"Hegemony with Chinese Characteristics: From the Tributary System to the

Belt and Road Initiative" (Routledge Contemporary China Series April

2021).

With as Doğan

explains, China appears to be moving from a period of being content with the

status quo to a period in which they are more impatient and more prepared to

test the limits and flirt with the idea of unification also with Taiwan. As the

US prepares for a period in which Xi Jinping is entering his third term,

there’s concern that he sees capstone progress on Taiwan as important to his

legitimacy and legacy, and that there is a perception that he is prepared to

take more risks. This matched a warning from

Admiral Philip Davidson, head of US Indo-Pacific command, who told senators

China could take military action “in the next six years”.

Admiral John

Aquilino, who is scheduled to succeed Davidson, this week told Congress that

there was a wide range of forecasts but “my

opinion is this problem is much closer to us than most think”.

“We've seen things

that I don't think we expected,” Aquilino told the Senate armed services

committee. “That's why I continue to talk about a sense of urgency. We ought to

be prepared today.” Aquilino said China had taken other “aggressive actions”,

including clashes with India on their border that suggested it was emboldened.

Kurt Campbell, the

top White House Asia official, said that while China was acting in an

increasingly aggressive manner in many areas, it was taking the most assertive

activities in its approach to Taiwan. “We have seen China become increasingly

assertive in the South China Sea . . . economic coercion against Australia,

wolf warrior diplomacy in Europe, and the border tensions with India,” he said.

“But nowhere have we seen more persistent and determined activities than the

military, diplomatic and other activities directed at Taiwan.”

The simulation

occurred as Chinese warplanes spent two days flying in and out of Taiwan’s air defence zone just days after Biden was sworn in. One US defence official said the incident was not the first time

China had simulated attacks on US ships. The revelations highlight that

the intense military competition between the two superpowers around Taiwan and

the South China Sea has not eased, posing a challenge to any attempts the Biden

administration might make to improve US

relations with Beijing.

Part 1: Overview of

the discussions following the 1919 or "Wilsonian moment,” a notion that

extends before and after that calendar year: Part

One Can a potential future Pacific War be avoided?

Part 2: Issues like

the Asian Monroe Doctrine, how relations between China and Japan from the 1890s

onward transformed the region from the hierarchy of time to the hierarchy of

space, Leninist and Wilsonian Internationalism, western and Eastern Sovereignty,

and the crucial March First and May Fourth movements were covered in: Part Two Can a potential future Pacific War be avoided?

Part 3: The important

Chinese factions beyond 1919 and the need for China to create a new

Nation-State and how Japan, in turn, sought to expand into Asia through liberal

imperialism and then sought to consolidate its empire through liberal

internationalism were covered in: Part Three Can a

potential future Pacific War be avoided?

Part 4: The various

arrangements between the US and Japan, including The Kellogg–Briand Pact or

Pact in 1928 and The Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament

of 1930. Including that American policy toward Japan until shortly before the Pearl

Harbor attack was not the product of a rational, value-maximizing decisional

process. Rather, it constituted the cumulative, aggregate outcome of several

bargaining games which would enable them to carry out their preferred Pacific

strategy was covered in: Part Four Can a

potential future Pacific War be avoided?

Part 5: The

Manchurian crisis and its connection to the winding road to World War II are

covered in: Part Five Can a potential future

Pacific War be avoided?

Part 7: Part Seven Can a potential future

Pacific War be avoided?

Part 8: While

initially both the nationalist Chiang Kai-shek (anti-Mao Guomindang/KMT),

including Mao's Communist Party (CCP), had long supported

independence for Taiwan rather than reincorporation into China, this started to

change following the publication of the New Atlas of China's Construction

created by cartographer Bai Meichu in 1936. A turning

point for Bai and others who saw China's need to create a new Nation-State was

the Versailles peace conference's outcome in 1919 mentioned

in part one. Yet that from today's point of view, the fall of Taiwan

to China would be seen around Asia as the end of American predominance and even

as “America’s Suez,” hence demolishing the myth that Taiwan has no hope is

critical. And that while the United States has managed to deter Beijing

from taking destructive military action against Taiwan over the last four

decades because the latter has been relatively weak, the risks of this approach

inches dangerously close to outweighing its benefits. Conclusion and outlook.

1. See Harada Diary,

August 21, 1931, 39, and October 2, 1931, 101-4 On reformists, see Sharon

Minichiello, Retreat from Reform: Patterns of Political Behavior in Interwar

Japan (Honolulu University of Hawai’i Press. 1984).

2. On

remembrance, see Naoko Shimazu Japanese Society at War: Death, Memory and

the Russo-Japanese War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2009) On the

development of the SMR zone before the 1931 crisis, see Yoshihisa Tak

Matsusaka, The Making of Japanese Manchuria, 1904-1932 (Cambridge.

MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), and Ramon H Myers, “Japanese Imperialism

in Manchuria: The South Manchurian Railway Company, 1906-1933,”

in The Japanese Informal Empire in China, 1395-1937, ed Peter Duus.

Ramon H Myers, Mark R Peattie, 101-32 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press 1989).

3. K.K.

Kawakami Manchukuo: Child of Conflict (New York Macmillan. 1933),

v-vi.

4. See Kevin

Doak Dreams of Difference : the Japan Romantic School and the Crisis of

Modernity (Berkeley: University of California Press. 1994); Tetsuo Najita and Harry' Harootunian, “Japanese Revolt against the

West: Political and Cultural Criticism in the Twentieth Century.” in The

Cambridge History of Japan. vol 6, ed Peter Duus, 711-74 (Cambridge Cambridge University Press, 1989), James Heiseg and John Maraldo, eds, Rude Awakenings: Zen,

the Kyoto School, and the Question of Nationalism (Honolulu University' of

Hawai'i Press, 1995), Aydin Politics of Anti-Westernism, esp. 111-21,

141-88, Jacqueline Stone “Japanese Lotus Millennialism.” in Millennialism,

Persecution, and Violence, ed Catherine Wessinger. 261-74 (Syracuse,

NY: Syracuse University Press, 2000), W. Miles Fletcher, The Search for a

New Order. Intellectuals and Fascism in Prewar Japan (Chapel Hill

University' of North Carolina Press. 1982).

5. K.K.

Kawakami Japan 's Pacific Policy' (New York E P Dutton & Co,

1922), 151.

6. Tojo quoted

in Perer Dims, “Introduction" in Harry D. Harootunian, Overcome by

Modernity: History, Culture, and Community in Interwar Japan, 2002.

7. Nagai quoted

in Jessamyn Reich Abel, Cultural internationalism and Japan’s wartime

empire: The turns of the kokusai bunka

shinkōkai, p. 37-38.

8. On

comparisons between Tokyo's declarations and liberal internationalism

especially the Atlantic Charter, see Akira Iriye, Power and Culture : The

Japanese-American War, 1941-1945, 1982,, esp

112-21, and Jessamyn R. Abel, The International Minimum: Creativity and

Contradiction in Japan’s Global Engagement, 1933-1964, 2015, 194-217.

Takeshi Fujnaiu Race for Empire: Koreans as

Japanese and Japanese as Americans during World War U (Berkeley:

University of California Press. 2011), 23.

9. See

Borgwardt New Deal for the World, 88-193, and Mazower, Governing

the World, 191-213.

10. Takashi

Fujitani, Race for Empire Koreans as Japanese and Japanese as Americans during

World War II,2011, 17. Mark Mazower. No

Enchanted Palace: The End of Empire and The Ideological Origins of the United

Nations, 2009, 19.

11. Oil FDR's

pragmatic liberalism, see Warren F. Kimball, The Juggler: Franklin

Roosevelt as Wartime Statesman, 1994, 185-200Alan Brinkley, The Publisher:

Henry Luce and His American Century, 2021, "61-65.

12. On the wars

final months, see Richard Frank Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese

Empire (New York Random House, 1999), and Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, Racing

the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan (Cambridge, MA

Belknap Press, 2006) Stimson knew about Kyoto s cultural treasures since at

least the 1920s, when he visited the city This study suggests that, given the

extent of KBS activities in the 1930s, a reasonable inference is that its

programs reinforced Stunsons awareness of Kyoto s

cultural importance. Still, why did Stimson, after approving the strategic

bombing of more than sixty Japanese cities, choose to spare a cultural center?

See Jason M Kelly. "Why Did Henry Stimson Spare Kyoto from the Bomb’’

Confusion in Postwar Historiography Journal of American-East Asian

Relations 19, no 2 (2012): 183-203.

13. Hirohito

surrender speech, https://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/hirohito.htm.

14. Truman statement,

August 16, 1945,

https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/library/public-papers/105/proclamation-2660-victory-east-day-prayer.

15. Officially

it was called the "Allied" occupation of Japan, but Gen. MacArthur

was the supreme decision maker.

16. The

occupation historiography is voluminous See especially John

Dower, Embracing Defeat Japan m the Wake of World War II (New York W.

W. Norton 1999), and Eiji Takernae Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of

Japan audits Legacy, trans Robert Ricketts and Sebastian Swann (New York

Continuum 2002). See also Hiroshi Knamura Screening

Enlightenment: Hollywood and the Cultural Reconstruction of Defeated

Japan (Ithaca. NY: Cornell University Press 2010) On race relations see

Yukiko Kosluro, Trans Pacific Racisms and the

U.S. Occupation of Japan (New York Columbia University Press, 1999).

17. See

Dower, Embracing Defeat. 277-301, and Bix, Hirohito, 541-618

Grew, Ten Years, 217. See also Masanon

Nakamura, The Japanese Monarchy: embassador Grew

and the Making of the “Symbol Emperor System” (Armonk, NY: M.E.

Sharpe, 1992) Aoki cited in Shibasaki, Kindai

Nihon, 128. To this day the Japan Society of Boston bestows an internationalist

award in Shigemitsu’s name On Yoshida see Dower, Empire and

Aftermath On the politics of surrender, see Marc Galliceluo, The

Scramble for Asia: U.S. Military Power in the Aftermath of the Pacific

War (Lanharn, MD:

Rowman & Littlefield 2008).

18. See Richard

Minear, Victors' Justice: Tokyo War Crimes Trial (Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press, 1972), and Yuma Totani The Tokyo War Crimes

Trial: Die Pursuit of Justice in the Wake of World War 11 (Cambridge. MA

Harvard University Asia Center 2009). Hirota was the lone civilian leader to be

hanged Matsuoka died in prison in 1946 from tuberculosis Konoe committed

suicide in December 1945.

19. Yasukuni Shrine

was founded in 1869 to memorialize Japan’s war dead See especially Aktko Takenaka Yasukuni Shrine: History,

Memory, and Japan's Unending Postwar (Honolulu University of Hawaii

Press, 2015), 131-89.

20. Harley F.

MacNair, "Japan and the Pacific war of Politics" 4, no. 3

(July 1942): 353, Kokusai Bunka Shinkokai:

Organization and Program (Tokyo: Kokusai Bunka Shuikokai

1949). 1.

For updates click homepage here