By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The Japanese Military Has a People

Problem

We pointed out the

population decline in Japan twice during the past years (here and here).

Whereby mor recently in 2024, the number of babies born in Japan fell to a

record low for the ninth year in a row. With about 1.6 million deaths and

720,988 births, there were about two deaths for every new baby born. Japanese

governments have proposed policies to reverse this trend, but they

have so far had little success. Thirty percent of the country’s population is

over the age of 65, and by 2070, this number is projected to be 40 percent. The

shrinking and aging of Japan’s population will transform Japanese society. But

it will have a particular effect on a major concern of the government: national

defense.

The Japanese

government passed a record defense budget in 2024, in line with its commitment

to increase its defense spending to two percent of its GDP by 2027.

The country’s new prime minister, Shigeru Ishiba, has

long sought to bolster Japan’s independent security capabilities and become a

more equal partner in its military alliance with the United States, which has

for decades pressured Japan to step up. Even before President Donald Trump’s

re-election, Japan had begun to make bolder military pledges. Under former

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, who led the country from 2021 to 2024, Japan

outlined plans to double its defense spending by 2027, loosen restrictions on

weapons development, and strengthen relations with like-minded countries around

the world.

The battering of the

Liberal Democratic Party in recent national elections has cast doubt on whether

these increased investments in defense will be possible. Although the LDP

remains the largest party in the National Diet, with Ishiba

as its leader, the party lost 56 seats in October 2024, failing to reach a

majority. Trump’s determination to put pressure on U.S. allies to pay their

“fair share” in maintaining security partnerships has only heightened the

stakes.

But even if Ishiba manages to garner the necessary political support

for more defense spending, Japan will have to face the dire demographic

headwinds. The decline of its population will almost certainly ensure that it

will fall short of the grand aspirations of Japanese policymakers and their

U.S. counterparts. Japan’s population is so old, and shrinking so quickly, that

it may not be able to field and fund an adequate defense force to meet growing

alliance demands in an increasingly volatile world. The size of its forces are

already vastly outmatched by its primary adversaries; Japan’s military is

one-tenth the size of China’s active forces and one-fifth of North Korea’s.

If present population

trends continue, they could severely limit recruitment for the already

chronically understaffed Japan Self-Defense Force, restrain the state’s ability

to tax the population to fund increased defense expenditures, and stifle the

innovation needed to compete in the defense sector. Without more people, Japan

will struggle not only to address its current security threats but also to play

the larger role in global affairs that Japanese and U.S. officials want it to. The

solution is at once simple and improbable. People need to have more

children, but few leaders are willing to say this out loud or to address the

obstacles that younger generations face in balancing their careers with their

family lives.

Strength in Numbers

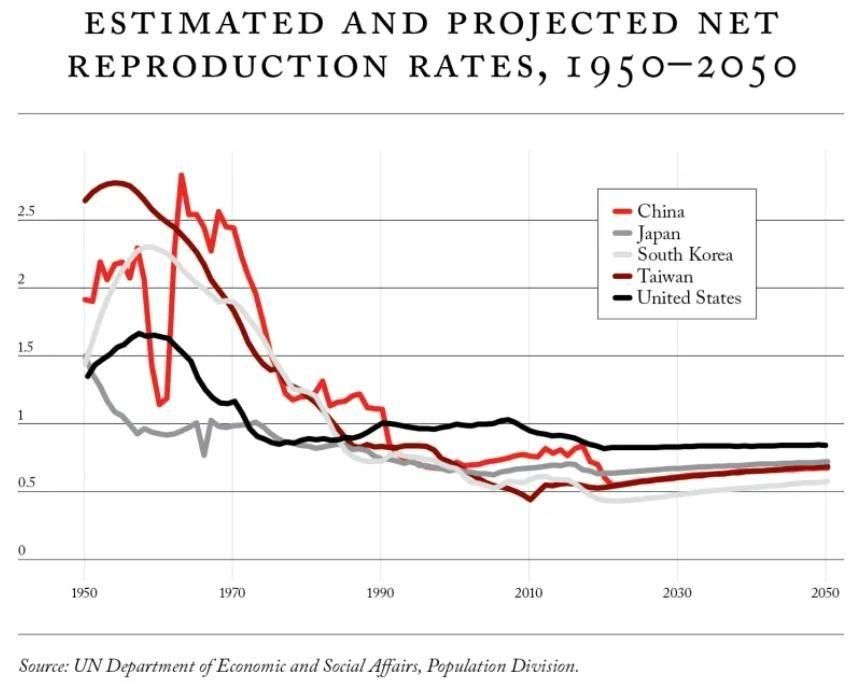

Japan is not the only

country suffering from these trends. Several U.S. allies and

partners have even lower fertility rates than Japan, facing declines that could

soon affect defense preparedness. Ukraine, which had a low birthrate even

before Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, now has one below one child per

woman, according to the UN Population Fund. Taiwan has a fertility rate of

around 0.87. (Demographers generally set the “replacement level,” at which a

country’s population remains stable, at 2.1 children per woman.) In South

Korea, academics and former military professionals have warned that a shrinking

population may force an eventual downsizing of its armed forces. And

policymakers in the United States will also have to face the reality that the

country’s falling birthrates and declining pool of eligible recruits could

eventually weaken U.S. forces if such trends continue.

The Japanese military

is particularly vulnerable to the consequences of demographic change. Since its

founding in 1954, the force has rarely met its recruitment targets, and decades

of economic stagnation, stigmas around military service, and recent sexual

harassment scandals have discouraged many young Japanese from enlisting.

Further, part of the reason Japan needs more troops is that the world is

becoming a more dangerous place, and many young people don’t want to put

themselves on the frontline. The Ministry of Defense has sought to appeal to

younger generations—by using celebrities, messages about peace, and anime in

its advertising, for example—and has raised the maximum age of recruits from 26

to 32. But these efforts have had little effect: in 2023, the ministry missed

its recruitment goal by more than 50 percent. That failure is not helped by

Japan’s ever-dwindling pool of possible recruits. In fact, over the last three

decades, the number of Japanese 18- to 26-year-olds, the primary recruiting population,

has declined by around 40 percent, from 17.43 million in 1994 to 10.2 million

in 2024. To meet its recruitment quotas for the coming decade, Japan would need

to eventually enlist more than one percent of its entire population—a herculean

task.

The effects of

dwindling numbers are already being felt across the ranks. In 2018, Noboru

Yamaguchi, a retired lieutenant general in Japan’s army, told me that the

warped ratio between senior and junior noncommissioned officers,

with many senior officers having only a few junior officers to supervise, has

hindered leadership development in the forces, leading to low morale and the

belief among senior officers that their job is unimportant and unfulfilling.

The inability to fill the military ranks will also eventually require painful

decisions over where to deploy the limited troops and what additional alliance

duties Japan can take on.

This challenge is

particularly alarming given the massive disparities between the present size of

the militaries of Japan and its closest allies compared with those of its

primary adversaries. In 2022, the number of Japanese military personnel stood

at a measly 227,843, while the United States had approximately 1.3 million

active forces and South Korea about 500,000 (Seoul has around a further 3

million reserve forces). China’s military, on the other hand, features

approximately 2 million active personnel, and North Korea’s about 1.2 million.

Indeed, when it comes to a possible conflict between Japan and China and North

Korea, retired Vice Admiral Yoji Koda told Reuters in 2022 that “manpower is

the real issue.”

Less Isn’t More

The effect of an

aging society on defense goes beyond recruitment. It also constrains the

national budget and stymies innovation. Japan’s new defense strategy, unveiled

in 2022, will require an estimated $300 billion through 2027. But

entitlement demands continue to dominate spending as the single largest

government expenditure, with over 37.7 trillion yen ($222 billion), or 33.5

percent of the national budget, allocated for social security in 2024—three

times the level in 1990. These demands will only grow as the population

continues to age and the workforce continues to shrink, with increasing

reliance on national health care and pension systems and a contracting tax pool

to fund them. The last three decades of economic stagnation—the stock market

only returned to its 1990 high in 2024—has further impeded efforts to raise

revenue, and efforts by Kishida to raise taxes for defense during his term

floundered.

Japan’s shrinking

population is complicating the country’s efforts to develop a larger indigenous

defense sector and decrease its reliance on U.S. weapons and munitions—a

crucial pillar of its defense overhaul. In 2023, Japan ranked 32nd on the

International Institute for Management Development’s World Digital

Competitiveness Ranking—its worst placement since the list began in 2017. The

country is facing engineer shortages in the vital chip industry, a shrinking

college-age population, and a falling number of doctoral degree recipients,

further weakening Japan’s prospects for economic productivity. This all means

less brain power for research and development and less physical labor for

assembly lines and transportation.

Japan’s Ministry of

Defense has been forthright in acknowledging that the demographic crisis will

affect national security. It outlined, in its new security strategy in 2022,

how the rapid population decline would require a more efficient use of its budget

and labor force. The Japanese military has tried to adapt its operations to a

smaller force, including by retrofitting vehicles and ships to operate with

fewer people and relying on advanced technology to carry out tasks

traditionally assigned to people. In December 2024, the Ishiba

government approved funding within its 2025 fiscal budget to increase wages and

implement new measures to improve work-life balance in the armed forces.

Yet even with a more

efficient and technologically enabled force, Japan’s military will still

require manpower. Applying a strategy of so-called minimal manning—working with

as few service members as possible—is not a solution but a Band-Aid. To

develop, produce, and operate new and increasingly indispensable technologies,

Japan will need more highly trained—and highly paid—soldiers for advanced

warfare. And infrastructure such as ships require several hundred people to

operate.

Fewer people will

therefore mean that troops have to endure longer deployments, commanders will

have less flexibility in deploying troops, casualties will exact a greater toll

on the capacities of the military, and the military will face greater constraints

in staffing new battalions and engaging in operations. All of this will put

further stress on current service members, making military jobs even less

desirable. This means that Japan cannot dedicate the resources needed to

become a stronger, more equal partner in its alliance with the United States,

never mind taking on a larger role in the Indo-Pacific.

Managing Expectations

Most of the Japanese

government’s proposals to address the country’s demographic challenges have

thus far not gained traction. In recent years, Japanese leaders have pursued

policies to encourage families to have more children. In 2023, for example,

Kishida introduced a plan to double government spending on childcare support by

2030, but the new childcare law passed in 2024 under Ishiba

amounts to less than half the amount Kishida outlined. Kishida’s other scheme,

to pay for college tuition for families with three or more children, was widely

criticized on Japanese social media as unserious and impractical and helped

sink his approval rating; although the measure passed, its effect will be

almost impossible to measure for at least two decades.

Another solution that

scholars and pundits often propose is to encourage more immigration; Japan has

historically not welcomed many immigrants, and some analysts imagine that a

significant reset of this policy will bring needed dynamism and vitality to the

economy and Japanese society. But immigration is not a permanent fix. Newcomers

could eventually replicate Japanese birthrates. They would also bring in new

costs, namely when it comes to social integration, and the government would

also eventually have to pay for further entitlements if immigrants settle and

age in Japan. And in terms of recruitment to the country’s military, only

Japanese citizens can join Japan’s armed forces.

In my discussions

with politicians, bureaucrats, and demographers in Japan last summer, many

feared that the solution to the demographic crisis is far too crass to say out

loud. Japan needs more consumers, soldiers, and taxpayers, and so families need

to have more children. But few ministries have implemented policies that will

address the stubborn gender norms that make it extremely difficult for women to

have children, maintain their careers, and enjoy a healthy work-life balance.

Invoking national security needs will do little to spur couples into action.

“If you want babies, you can do it and the government will support it,” one

Japanese official told me. “But to argue that we have to increase the birthrate

because of our national security, it is a very difficult thing to put in the

right context.”

The United States

can pester Japan all it wants about dedicating more resources to defense, but

Japan is not likely to fulfill either country’s dream of a stronger, more equal

U.S.-Japanese alliance. If it were up to Ishiba,

Japan would already be on its way to reaching that goal. But there are few

guarantees that Ishiba will be able to follow through

on the agenda set by his predecessor, especially after his party lost its

legislative majority in October. Doubling Japan’s defense spending now will

strengthen the country’s national security, but such increases are unlikely to

stretch into the long term, Japanese troops are not likely to be able to deploy

in large numbers abroad, and the Japanese government will not eagerly turn to

military force over diplomacy. Both Tokyo and Washington must adjust their

expectations for what Japan—and other partners facing similar demographic

declines—can reasonably achieve, especially in the long term, when the

consequences of an aging and shrinking population will be even more severe.

For updates click hompage here