By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

On August 6, 2024,

Ukrainian forces launched a surprise cross-border offensive into Russia’s Kursk region—the biggest foreign incursion into

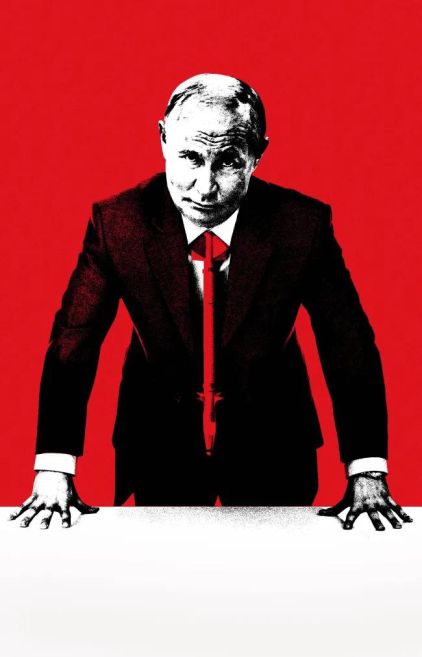

Russian territory since World War II. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s

response was telling. Days after Ukraine’s offensive, Putin railed against the

United States and Europe. “The West is fighting us with the hands of the

Ukrainians,” he said, reiterating his view that Russia’s war in Ukraine is in

fact a proxy battle with the West. But he initiated no immediate military

counterattack. Putin was unwilling to divert substantial numbers of troops away

from their operations in eastern Ukraine even to recover territory back home.

Three months later, with Ukrainian forces still in Kursk, Moscow instead

brought in North Korean troops to help push them out—the first time in more

than a century that Russia has invited foreign troops onto its soil.

Moscow’s actions

underscore how, after almost three years since Russia’s full-scale invasion of

its neighbor, Putin is now more committed than ever to the war with Ukraine and

his broader confrontation with the West. Although the conflict is first and foremost

an imperial pursuit to end Ukraine’s independence, Putin’s ultimate objectives

are to relitigate the post–Cold War order in Europe, weaken the United States,

and usher in a new international system that affords Russia the status and

influence Putin believes it deserves.

These goals are not

new. But the war has hardened Putin’s resolve and narrowed his options. There

is no turning back: Putin has already transformed Russia’s society, economy,

and foreign policy to better position the Kremlin to take on the West. Having accepted

the mantle of a rogue regime, Russia is now even less likely to see a need for

constraint.

The stage is set for

the confrontation with Russia to intensify, despite the incoming Trump

administration’s apparent interest in normalizing relations with Moscow. The

war is not going well for Ukraine, in part because the limited assistance the

West has sent to Kyiv does not match the deep stake it claims to have in the

conflict. As a result, Russia is likely to walk away from the war emboldened

and, once it has reconstituted its military capacity, spoiling for another

fight to revise the security order in Europe. What’s more, the Kremlin will

look to pocket any concessions from the Trump administration for ending the

current war, such as sanctions relief, to strengthen its hand for the next one.

Russia is already preparing the ground through the sabotage and other special

operations it has unleashed across Europe and through its alignment with other

rogue actors, including Iran and North Korea. European countries are only

slightly more prepared to handle the Russian challenge on their own than they

did three years ago. And depending on how the war in Ukraine ends, the

possibility of another war with Russia looms.

The question is not

whether Russia will pose a threat to the United States and its allies but how

to assess the magnitude of the danger and the effort required to contain it.

China will remain the United States’ primary competitor. But even with much of its

attention called to Asia, Washington cannot ignore a recalcitrant and

revanchist adversary in Europe, especially not one that will pose a direct

military threat to NATO members.

The Russian problem

is also a global one. Putin’s willingness to invade a neighbor, assault

democratic societies, and generally violate accepted norms—and his seeming

ability to get away with it—paves the way for others to do the same. The

Kremlin’s provision of military equipment and know-how to current and aspiring

U.S. adversaries will amplify these threats, multiplying the challenges that

Washington will face from China, Iran, North Korea, and any other country that

Russia backs.

The United States and

Europe, therefore, must invest in resisting Russia now or pay a far greater

cost later. The incoming Trump administration, in particular, does not have the

luxury of shoving Russia down its list of policy priorities. If Putin sees Washington

doing so, he will grow only more brazen and ambitious in his efforts to weaken

the United States and its allies, both directly and through the axis of

upheaval that Russia supports. To prevent that outcome, Washington and its

allies must help Ukraine strengthen its position ahead of negotiations to end

the current war. The United States is right to prioritize China, but in order

to effectively compete with Beijing, it first needs to set European security on

the right path. Washington must remain the primary enabler of that security for

now, while making sure that Europe ramps up the investments required to better

handle its own defense in the years ahead. By taking the steps necessary to

counter Russia today, the United States and Europe can ensure that the threat

they face tomorrow will be a manageable one.

In Too Deep

Putin has changed

Russia in ways that will ensure it remains a challenge to the West as long as

he is in power and likely well beyond. Confrontation is now the hallmark of

Russia’s foreign policy, with Putin citing his country’s “existential struggle”

with the West to justify his regime and its actions. This idea of a Russian

civilization in constant conflict with its Western foes strengthens the

ideological foundation of his rule—a source of legitimacy he now needs to

safeguard his hold on power.

Putin’s increased

reliance on repression has generated risks to the stability of his regime.

Political science research shows that repression is effective in the sense that

it increases autocrats’ longevity in office. But depending too heavily on it,

as Putin has done, can raise the prospect that leaders will make destabilizing

mistakes. Heavy-handed tactics compel people to mask their private views and

avoid sharing anything but what the government wants to hear, which means the

autocrat, too, loses access to accurate information. High levels of repression

also create a rising reservoir of general dissatisfaction, so that even a small

outburst of discontent can quickly spiral into trouble for the regime. To

mitigate these risks and reinforce his hold on power, Putin has used his

control over the information environment to convince the Russian people that

their country is at war with a West that wants to break it apart.

Putin has also

reoriented the Russian economy around his war. Russia’s defense spending is set

to reach its highest point since the collapse of the Soviet Union, with $145

billion allocated in the 2025 budget—the equivalent of 6.3 percent of GDP and

more than double the $66 billion Russia budgeted for defense in 2021, the year

before the invasion. And the true amount of such spending will likely be

higher, possibly exceeding eight percent of GDP, once other, unofficial forms

of defense-related expenditures are accounted for. (When also adjusting for

considerable differences in purchasing power parity between Russia and the

United States, Russia’s actual defense spending is much higher than $145

billion, exceeding $200 billion.) Russian factories producing military

equipment have added shifts to increase production; workers have moved from

civilian to military sectors, where the wages are higher; and payouts for

military service have skyrocketed. The war has become a wealth transfer

mechanism channeling money to Russia’s poor regions, and many economic elites

have moved into the defense sector to cash in on lucrative opportunities.

Elites have, by now, adjusted to the system’s current configuration, enabling

them not just to survive but to profit from it.

Having gone through

the pain of shifting the economy to a wartime footing and feeling the pressure

of new vested interests, Putin is unlikely to undo these changes quickly. After

the fighting in Ukraine ends, he will probably instead look to justify the continuation

of the wartime economy. Such was the inclination of Soviet leader Joseph

Stalin, who, after the Allied victory in World War II, soon began to speak of

Moscow’s new five-year plans as necessary preparation for the next inevitable

war.

Russian foreign

policy is also transforming in ways that will be difficult to undo. The

invasion of Ukraine has made it impossible for Russia to build ties with the

West, and Moscow has had to look for opportunities elsewhere. Its deepening

partnerships with China, Iran, and North Korea may have been driven largely by

necessity: Russia needs their help to sustain its economy and warfighting

machine. But Moscow also understands that by working with these countries, it

is in a better position to sustain a long-term competition with the United

States and its allies. Not only does their support make Russia less isolated

and less vulnerable to the United States’ tools of economic warfare; Russia

also benefits from having cobelligerents working in tandem to weaken the West.

The Kremlin has gone all in on these partnerships, having abandoned caution in

cooperating with North Korea, overcome its concern with overdependence on

China, and elevated relations with Iran beyond

transactional engagement. All of this amounts to a new strategy for Moscow, one

that will not simply disappear after the fighting in Ukraine subsides or ends.

Military drills in the southern Krasnodar region,

Russia, December 2024

From now on, the

Russian military will have a duality to it, with areas of strength but equally

prominent weaknesses. On the one hand, it has become much better at dynamic

targeting, precision strikes, the integration of drones in combat operations,

and more sophisticated methods of employing long-range precision-guided

weapons. Russia has adapted to—and in some cases developed effective tactics to

counter—the Western capabilities it confronted in Ukraine. Over time, Russian

forces reorganized logistics and command and control, coming up with ways to

reduce the efficacy of Western equipment and intercept Western munitions, and

they have learned to operate with the presence of Western long-range

precision-guided weapons, intelligence, and targeting.

For NATO, this ought

to set off alarms. Some analysts argue that the way Ukraine is fighting now is

not the way NATO would fight in a potential future war with Russia. They

contend specifically that NATO would quickly earn and maintain air superiority,

changing the nature of the conflict. Although this may be true, airpower will

not solve every battlefield challenge NATO might face. And most European air

forces lack munitions for a sustained conventional war. The time it would take

to deplete their arsenals can best be measured in weeks and in many cases days.

On the other hand, a

substantial percentage of the Russian ground force will likely continue to

field dated Soviet equipment, and it will take years to rebuild force quality

and replace the officers lost in Ukraine. The outlook for Russia’s defense

capacity will also depend on whether its economy is running flat out and the

defense sector has already maximized production or if there is still room for

production to increase as new and refurbished plants and facilities come

online. Overall, the Russian military will remain a patchwork, with some parts

more advanced and capable than they were at the start of 2022 and other parts

still using equipment from the middle of the Cold War, if not earlier. But the

chances of the Russian armed forces being decisively knocked out and unable to

pose a major threat for a prolonged period are low.

Russia Reloads

Russia’s military

threat is not going away, either. The question of Russian military

reconstitution is not an if but a when. Even if Russia cannot sustain its

current wartime spending, the defense budget is likely to remain substantially

above prewar levels for some time to come. The Russian military, too, is

unlikely to shrink back to the relatively small army Russia fielded before the

war. One lesson that Russia’s military brass took from Ukraine is that the

Russian army was not “Soviet” enough in that it lacked mass and the capacity to

replace losses. In reality, the Russian military was stuck in a halfway state,

having acquired some advanced or modernized capabilities but also retaining

some Soviet-era characteristics, including conscription and a culture of

centralized command that discouraged initiative. Now, Russia is likely to

maintain a large overall force with an expanded structure and greater manpower

allocation, although it will still depend on mobilization in the event of war

to reduce the cost of its standing army.

Reconstitution is

about not just materiel but also the capacity to conduct large-scale combat operations.

The Russian military has shown that it can learn as an organization; it is

capable of scaling the deployment of new technology such as drones and

electronic warfare systems onto the battlefield, and it will be a changed force

after its experience in Ukraine. Despite its initial poor showing, the Russian

military has demonstrated staying power and the ability to withstand high

levels of attrition.

Russia’s military

reconstitution will face headwinds, especially from the country’s limited

defense industrial capacity and skilled labor shortage. Russian industry has

not been able to significantly scale the production of major platforms and

weapons systems. Labor and machine tools remain major constraints because of

Western sanctions and export controls. Russia has still been able to

significantly increase the production of missiles, precision-guided weapons,

drones, and artillery munitions, and it has set up an effective repair and

refurbishment pipeline for existing equipment. But it is also drawing from

aging stocks that it inherited from the Soviet Union for much of its land force

equipment. Thus, as it expands its forces and replaces losses, it is depleting

its resources.

A Growing Gap

The risks from the

reconstitution of Russia’s military are compounded by the West’s lackluster

response to rising Russian aggression. Europe still has a long way to go before

it is prepared to handle the threat from Russia on its own. European defense production

is insufficient to meet rearmament goals, despite Europe’s advantages in

capital, machine tools, and labor productivity. European countries have

substantially depleted their stocks by transferring older equipment to Ukraine,

limiting their militaries’ mobilization potential. These countries will soon

face the dual pressure of funding Ukraine’s war effort and recovery while

replacing their own expended war materiel. Given how limited their arsenals

were to begin with, if they want to be equipped to handle Russian belligerence,

they will need to build well beyond 2022 levels—not just restore what was lost.

Current trends

suggest that although European defense spending is likely to rise, the

increases may not be enough to significantly expand military capability. There

are exceptions, such as Poland and the Baltic states. But many countries with

large budgets, such as Italy and Spain, are lagging behind. Many have yet to

meet the commitment made by all NATO allies to spend the equivalent of two

percent of GDP on defense. Across Europe, defense production is constrained by

industrial capacity, the slow pace of finalizing contracts, and competing

budgetary imperatives. All these issues can be overcome with sufficient

political will, but European leaders first have to be clear-eyed in their

assessment of the security environment. The United States is not going to

significantly expand its presence in Europe; at best, Washington’s commitment

to European security will remain constant as it pushes Europe to do more, and

there is a real risk that it will turn its focus elsewhere. Europe must prepare

to foot more of the bill to ensure that Ukraine is in a position to defend

itself and to deter future Russian aggression against both Ukraine and Europe

as a whole.

American leaders, for

their part, will have to be realistic about Europe’s capabilities. Even those

countries that are now investing heavily in equipment and procurement are still

having issues recruiting, retaining, and training sufficient forces. And defense

spending does not easily translate into the ability to conduct large-scale

combat operations. Modern operations are complex, and European countries

generally cannot execute them without U.S. support. Most militaries on the

continent have coevolved to complement the U.S. military rather than to operate

independently.

European militaries

and NATO have made some progress matching their defense investments with the

requirements of regional defense plans. But the forces active on the continent

are not capable of handling a large-scale war on their own. They would find it

difficult to agree on who would lead such an operation and who would provide

the necessary supporting elements. European militaries would struggle to defend

a fellow NATO member, or Ukraine, without U.S. help—a dependence that

Washington has, to some extent, perpetuated. Thus, although the United States

should continue to press its European allies to take on more of the security

burden, Washington must appreciate that it will take a long time for Europe to

get there.

After a Russian drone strike in Kyiv, Ukraine,

November 2024

The Rising Risk of War

Europe and the United

States are not preparing for some far-off threat. Moscow is already waging an

unconventional war against Europe. Within the past few years, suspected

Russian-backed actors have set fire to warehouses in Germany and the United

Kingdom that were full of arms and ammunition for Ukraine, tampered with water

purification centers in Finland, pushed migrants from the Middle East and North

Africa crossing through Belarus and Russia to the borders of Poland and

Finland, targeted railway infrastructure in the Czech Republic and Sweden,

assassinated a Russian military defector in Spain, and even plotted to

assassinate the German head of a major European arms manufacturer. The

Kremlin’s goal with these measures is to show European governments and citizens

that Russia can retaliate for their support for Kyiv.

Yet once the war in

Ukraine ends, Russia’s efforts won’t subside. Moscow’s broader aim in pursuing

these tactics is to degrade the West and its ability to counter Russia. It

wants to weaken Western societies, drive wedges between the United States and

Europe, reduce Europe’s capacity for collective action, and convince Europeans

that it’s not worth the trouble to push back against Moscow. Part of its

strategy is to use nuclear intimidation, such as the recent changes to Russian

nuclear doctrine that seem to lower the threshold for nuclear use, to heighten

Western fears of confronting Russia.

Russia is not in a position

to challenge NATO directly. The current low-scale conflict with NATO countries

is likely to persist until the Russian military rebuilds—a process that could

take years. But the Kremlin will then be looking for opportunities to further

undermine NATO. Moscow will still have reason for caution, not least because it

considers the alliance to be a superior force, but it may be tempted if it

becomes clear that the allies—the United States the most important among

them—lack the resolve for collective defense. The Kremlin would be most prone

to make this calculation if the United States is engaged in a major conflict with China in the Indo-Pacific, which

Washington has deemed its highest national security priority. Should the

Kremlin calculate that Washington would not or could not come to Europe’s

defense and that Europe alone would not be capable of victory, then Moscow could

target a country on NATO’s eastern flank, daring NATO to respond.

The picture is

further complicated by the Kremlin’s propensity for both risk-taking and

miscalculation. Already, Moscow has seriously misjudged its ability to rapidly

defeat the Ukrainian military and to shake Western resolve. Personalist

autocrats such as Putin are the type of leader most inclined to make mistakes,

in part because they surround themselves with yes men and loyalists who tell

the leaders what they want to hear. Washington and its allies should thus not

sleep comfortably even if NATO forces are well equipped to defeat the Russian

military. Having confidence that NATO would prevail in the end is not enough,

especially having observed what Ukraine is experiencing now: cities destroyed,

tens of thousands killed, millions made refugees, and areas under prolonged

Russian occupation. Even if Russia were defeated today, a future war with

Russia could be devastating for the country it invades and for the NATO

alliance. The imperative for the United States and NATO is to make sure Moscow

never tries.

Aiding and Abetting

The confrontation

with Russia will remain most intense in Europe, but the challenge from Moscow

is global. Although the United States and Europe levied significant costs on

Russia in the aftermath of its invasion of Ukraine, Moscow has circumvented

Western sanctions and export controls and defied predictions of international

isolation. In October, Russia hosted the annual summit of BRICS (whose first

five members were Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), with dozens

of world leaders in attendance, demonstrating a growing interest in the group’s

role as a platform for challenging Western power and influence.

The more that Putin

clashes with the United States and its allies and is perceived to get away with

it, the more other countries will be emboldened to issue challenges of their

own. Russia’s war in Ukraine is exposing not only a gap between the West’s rhetoric

and its practical commitment but also the limits of Western military capacity.This is not to say that a seeming Russian success

in Ukraine would automatically prompt Chinese leader Xi Jinping to invade

Taiwan; other factors, such as the military balance of power in the region and

political imperatives in Beijing, will be more decisive in shaping Xi’s

calculus. Yet China is taking notes, as are onlookers around the world.

Would-be Western adversaries are assessing the price of using force and

considering what they might expect were they to launch a similar gambit.

Likewise, the inadequate response to Russian sabotage in Europe might encourage

other potential foes to get in the game.

Not content to simply

inspire, Moscow is also actively aiding opponents of the West. Russia has lent

support to rogue actors across the Sahel region of Africa, dispensing materiel

and diplomatic backing that enabled military officials to forcibly seize power

in Mali in 2021, in Burkina Faso in 2022, and in Niger in 2023 and subsequently

curtail ties with the United States and Europe. Russia is also sending arms

into Sudan, prolonging the country’s civil war and the resulting humanitarian

crisis, and has lent support to the Houthi militias in Yemen, who have attacked

vessels in the Red Sea, disrupting global trade, and have fired missiles at

Israel, a close U.S. ally.

Although the

consequences for the United States of any one of these developments may be

limited, in aggregate, Russia’s actions are magnifying the challenges facing

Washington. In Niger, Russian support eased the new government’s decision to

force the United States to abandon a base it used to launch counterterrorism

missions in the Sahel. If Russia were to ramp up its support for the Houthis

and provide them with antiship missiles, the militant group would be better

able to strike commercial vessels in the Red Sea and raise the threat to the

U.S. and European warships defending them. Once the fighting in Ukraine ends,

Russia could devote significantly more resources and attention to the Houthis

and other groups or countries that threaten U.S. interests.

Some observers have

held out hope that China’s concern for its economic interests will induce it to

rein in Russia. But Beijing’s actions so far indicate no such effort. China did

not object to Russia’s support for the Houthis, despite the risks to global

shipping. Even if Beijing is wary of Russia’s deepening relations with North

Korea, it is unlikely to intervene, not least because it does not want to spoil

its long-standing relationship with Pyongyang. Instead, China seems content to

let Russia roil the international system and take advantage of the resulting

disorder to further its own rise. If there is to be any check on Russia’s

destabilizing activities, then, it will have to come from the West.

The Axis of Upheaval

Russia’s effort to

support China, Iran, and North Korea is among the most pernicious problems

posed by Moscow. Russia’s war in Ukraine has spurred a level of cooperation

among those countries that few thought was possible, and the Kremlin has

operated as the critical catalyst. The arrival of North Korean troops in Russia

is a worrisome reminder that with highly personalized authoritarian regimes at

the helm in Russia and North Korea and with the regimes in China and to a

lesser extent Iran moving in this direction, cooperation can evolve rapidly and

in unpredictable ways.

A body of political

science research shows that this particular type of regime tends to produce the

most risky and aggressive foreign policies. Countries with personalist

authoritarians at the helm are the most likely to initiate interstate

conflicts, the most likely to fight wars against democracies, and the most

likely to invest in nuclear weapons. Russia’s growing military and political

support for China, Iran, and North Korea will only facilitate these tendencies.

And Moscow, by now having shed its concern with its international reputation,

is likely to become even less constrained in its willingness to aid even the

most odious of regimes.

Russian support for

fellow members of this axis of upheaval, therefore, could bring disorder to key

regions. Take the Chinese-Russian relationship. Although Moscow has supplied

Beijing with arms for years—including advanced fighter aircraft, air defense systems,

and antiship missiles—their defense ties have deepened at an alarming rate. In

September, for example, U.S. officials announced that Russia had provided China

with sophisticated technology that will make Chinese submarines quieter and

more difficult to track. Such an agreement was hard to imagine just a few years

ago, given the sensitive nature of the technology. With Beijing and Moscow

working together, the U.S. military advantage over China could erode, making a

potential conflict in the Indo-Pacific more likely if China believes it has the

upper hand.

Russia’s support for

Iran is similarly troubling. Moscow has long sent tanks, helicopters, and

surface-to-air missiles to Tehran, and it is now supporting the Iranian space

and missile programs. Since Russia’s intervention in Syria in 2015 to shore up

the rule of President Bashar al-Assad—joining Iran in that effort—Moscow and

Tehran’s increased interaction has enabled them to overcome a historic distrust

and build the foundations of a deeper and more durable partnership. A decade

ago, Russia participated (if warily) in the international negotiations that led

to the 2015 Iran nuclear deal. But today, Moscow seems far less interested in

arms reduction or nonproliferation. As the wars in the Middle East degrade

Iran’s proxies and expose the limits of its ability to deter Israel, Tehran’s

interest in acquiring a nuclear weapon may grow—and it may turn to Russia for

help. That help could be overt, with Moscow offering the expertise needed for

weapon miniaturization, for example, or it could be indirect, with Russia

shielding Tehran from UN action. Iran’s acquisition of a nuclear weapon, in

turn, could send other countries in the region, such as Egypt or Saudi Arabia,

scrambling to nuclearize, effectively ending the current era of

nonproliferation in the Middle East.

In the case of North Korea,

Russia’s support raises the risk of instability on the Korean Peninsula.

According to South Korean officials, Pyongyang has requested advanced Russian

technologies to improve the accuracy of its ballistic missiles and to expand

the range of its submarines in return for North Korea sending its troops,

ammunition, and other military support to Russia. And it is not just advanced

equipment that could make North Korea more able and, perhaps, more willing to

engage in a regional conflict. North Korean troops deployed to Russia are now

gaining valuable battlefield experience and insight into modern conflict.

Moscow and Pyongyang also signed a treaty in November establishing a

“comprehensive strategic partnership” and calling on each side to come to the

other’s aid in case of an armed attack—an agreement that could potentially

bring Russia into a fight between North Korea and South Korea.

It is tempting to

imagine that if the United States presses Ukraine to end the war and pursues a

more pragmatic relationship with Russia, Moscow’s cooperation with members of

this axis could lessen. Yet this is wishful thinking. The growing ties among China,

Iran, North Korea, and Russia are driven by incentives far deeper than the

transactional considerations created by the war in Ukraine. If anything,

concessions made to Russia to end the war would only enhance the Kremlin’s

ability to help its partners weaken the United States.

Order of Operations

Russian ambitions may

not stop at Ukraine, and in the absence of Western action today, the costs of

resisting Russian aggression will only rise. Russia is a declining power, but

its potential to stir conflict remains significant. Thus, the burden of deterrence

and defense against it is not going to lighten in the near term. And because

changes to defense spending, procurement, and force posture require significant

lead times, Washington and its allies must think beyond the current war in

Ukraine and start making investments now to prevent Russian opportunistic

aggression later on. Europe must channel its rising defense spending into

expanding the organizational capacity and logistical support necessary to make

independent action possible if the U.S. military is engaged elsewhere. Giving

in to Russia’s demands will not make it any easier or cheaper to defend

Europe—just look at the events of the past two decades. At every turn—the war

in Georgia in 2008, Russia’s first invasion of Ukraine in 2014, and its deployment

of troops to Syria in 2015—Putin has grown only more willing to take risks as

he comes to believe that doing so pays off.

Washington

undoubtedly has competing priorities that will shift its focus away from the

Russian threat—China foremost among them. But to effectively address China,

Washington must first set European security on the right path. The United

States cannot simply hand off European security to a Europe that is not yet

capable of managing the Russian threat. If Washington downsized its commitment

to Europe prematurely, Moscow could take it as a sign of growing U.S.

disinterest and use the opportunity to press ahead.

Ukraine Problem First

The prioritization of

U.S. policies is important, but so is the sequencing. The Trump administration

will first have to manage the war in Ukraine. Helping Ukraine achieve an end to

the war on favorable terms is the clearest way to reduce the threat of aggression

from Russia and the axis of upheaval that supports it. This agreement would

need to be embedded in a larger strategy to contain Russia and preserve

Ukrainian security. NATO should do away with the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act,

which prohibits permanent deployments of allied forces near Russia, and station

troops on NATO’s eastern flank. The alliance should also raise its members’

defense spending targets, increase its readiness, and improve its ability to

deploy forces to defend threatened member states. Western countries should

maintain and better enforce sanctions and export controls on Russia for at

least as long as Putin remains in power. Western countries must also invest in

Ukraine’s defense sector and ensure that Ukraine can sustain its own armed

forces to deter Russia from invading again. Although these measures would not

end the confrontation with Russia, they would blunt Moscow’s ambitions and its

capacity to both stir conflict in Europe and strengthen its partners in other

parts of the world.

The Trump

administration must also preserve the United States’ role as the primary

enabler of European security while working to reduce the burden of its

maintenance. European states must become more capable of collective action that

does not require U.S. aid. They may still rely on the United States in some

circumstances, but the extent of their dependence can be significantly reduced.

Over time, the United States will become freer to focus on China as it shifts

more defense responsibilities to Europe. And in the meantime, it will avoid an

overly hasty, chaotic pivot that would only encourage and embolden Moscow and

could result in Russia eventually launching a reckless war, either against NATO

or once again against Ukraine.

There is no easy

resolution to the West’s confrontation with Russia. Russian revisionism and

aggression are not going away. Even if the current war in Ukraine is settled

via an armistice, without some kind of security guarantee for Ukraine, another

war is likely. Ignoring Russia or assuming that it can be easily managed as the

United States turns its attention to China would only allow the threat to grow.

It would be far better for the United States and its allies to take the

challenge from Russia seriously today than to let another conflict become a

more costly proposition tomorrow.

For updates click hompage here