By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

NATO And Artikel Five

The past 24 hours

have shown how delicate the situation could become on Ukraine’s borders with Nato countries, including Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Moldova,

and Romania. Since the Russian invasion at the end of February, the big fear

for the west’s most important military alliance is that hostilities could spill

over into one of those countries, forcing Nato to

intervene and become embroiled in the conflict.

These fears have

surfaced again after a Russian-made missile landed on the village of Przewodów a few miles inside the Polish border on November

15, killing two farmers. This immediately led to frantic speculation that the

missile could have been launched by Russia, which could have led Poland to

invoke Article 5 of the Nato treaty.

Article 5 does

not demand a

military response from

Nato member states. But they are mandated to “assist

the Party or Parties so attacked by taking forthwith, individually and in

concert with the other Parties, such action as it deems necessary, including

the use of armed force.”

Scrambling For The Facts

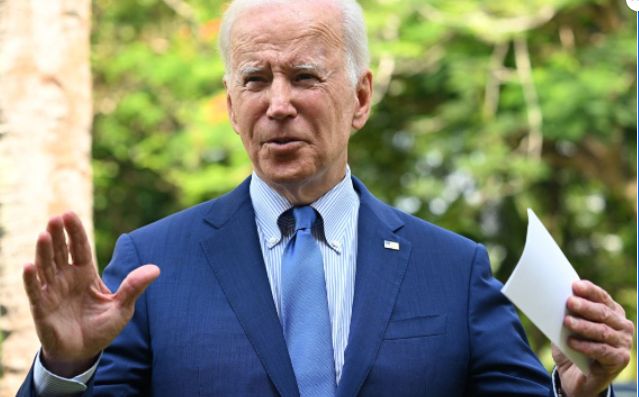

President Joe Biden

was asleep on the other side of the world when aides woke him up in the middle

of the night there with urgent news: a missile had

struck Poland and

killed two people.

By 5:30 am local time

in Bali, where the president was attending the

G20 summit, Biden,

still in a t-shirt and khakis, was on the phone with his Polish counterpart

Andrzej Duda seeking clarity on where the missile had

come from – a critical fact due to the potentially dire implications of a

Russian missile strike on a NATO ally.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken, who was traveling

with Biden, had also been roused with a knock on the door by his body man

around 4 a.m. local time with news of the explosion, a US official said – news

that most US officials only discovered from public reports and conversations

with Polish officials.

After several anxious hours, Biden was the first to

relieve some of the tension, telling reporters that initial information

suggested Russia did not launch the missile.

But The Incident Has Also Created Some Cracks In The

West’s Alliance With Ukraine.

By Wednesday, multiple senior US officials were

publicly saying that intelligence pointed to the explosion from a Ukrainian air

defense missile that landed in Poland accidentally. An official said that the

US had also shared the classified information with allies before Wednesday

morning’s North Atlantic Council meeting at NATO headquarters.

Zelensky, on

Wednesday afternoon, insisted that Ukrainian forces did not launch the missile.

He told reporters in Kyiv, “I do not doubt that it was not our missile,” citing

reports he had received from the command of the Ukrainian armed forces and the

Air Force.

Zelensky also

expressed frustration that Ukrainian officials had not been permitted to join

the joint Polish-US investigation of the site and said he wanted to see “the

number on the missile because all missiles have numbers on them.”

But Zelensky concluded on Thursday that he did

not fully know what had happened in Poland.

The Polish Viewpoint

If the conflict in

Ukraine is rewriting the history of central and eastern Europe, then so is the

history of the north Atlantic alliance.

Two people were

killed on Tuesday evening in Polish territory, struck, it seems, by a

Russian-made missile. The US president, Joe Biden, and the Warsaw

government sought to dial down the tension, saying on Wednesday that

the missile most probably came not from Russia but from Ukrainian air defense.

The question for

Poland, however, remains, as it would for any Nato member

state, especially one living in Russia’s shadow: what if this, or a similar

incident, turned out to be a deliberate Russian operation after all? What

protection could it expect from the US and its other Nato

allies?

Under Article 5 of

the Nato treaty, an armed attack on one ally is

regarded as an attack on all. But what constitutes an armed attack? And what

would Nato solidarity mean in practice? The answer

that Poland and other smaller Nato

members (as well as the Kremlin) are learning would appear to be “it depends”.

The possibility of a

Russian missile landing on Polish soil or on the territory of one of the Baltic

states, either by accident or by design, has hung over the Ukraine crisis for

nine months. In the disinformation age, one could imagine Moscow owning up to

an “accident” and Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov, with a

characteristically sinister smile, expressing “regret.”

So at what point does

a Nato member get to claim that it needs to invoke

Article 5’s protection, as the organization’s territorial integrity has been

violated? Russia has violated Scandinavian – Danish and Swedish – airspace

on countless

occasions. But Nato’s supposedly impassable red lines appear mutable when

nuclear-armed global conflict is at stake.

For the citizens of

Poland, who now have two dead compatriots, “it depends” begins to sound as if

the line between war and peace is being deliberately blurred. In the coming

days and weeks, Russia’s immediate neighborhood will find out what Nato membership and US military support is worth.

A forensic

investigation into the circumstances of Tuesday’s incident is essential. But

the problem remains. The cool heads of diplomats will. We must hope and

continue to prevent a dangerous escalation. But don’t be surprised if hotheads

in the urban and rural areas bordering Russia react differently. What, they now

ask, if another missile strays into Nato territory,

killing more civilians?

The collective fear

reawakened across eastern Europe by this war is visceral. Our recurring

nightmare is of Russian troops and weapons breaching the Polish border again,

as they have done many times over the past 300 years. In a survey conducted

after Russia invaded Ukraine, 84% of Polish

citizens said they

feared the war could spill into Poland. I think about it every day, one

man living on the Polish-Russian border. “They could come any time. Kill us in

our beds.”

For most eastern

Europeans, the war in Ukraine is seen not as a single event but as a process of

creeping and always escalating Russian aggression. This view reflects a

particular fatalism and distrust of our western allies. And while the reaction

of the Polish government has been profoundly measured, social media reactions

show that many citizens are convinced that the situation has just turned their

fears into facts. Anxieties that lives could be lost because of the war,

including those living on Polish territory, have now proved tragically justified.

These regional fears

translate into an expected outcome of the war. For many Poles, like their

neighbors in the Baltic states, there are only two acceptable scenarios in the

wake of the Ukraine war. The first is the utter destruction and defeat of Putin’s

Russia, similar to Germany’s wipeout in 1945. And if this is not an option,

they want at least a repeat of 1991, the collapse of the Russian empire. There

is no third way.

Conclusion

There is no question

that Ukraine deserves an ample voice in determining its fate, but the outside

powers supporting Ukraine also get a voice. “Standing with Ukraine” does not

and should not mean placing our interests and concerns on hold, significantly when

they do not always overlap with Kyiv’s interests or objectives. No responsible

world leader can or should sacrifice their country’s interests for another’s,

and a good ally tells its partners if it thinks they are acting unwisely.

Nor should we; first

of all, we should not forget that “accidental” or “inadvertent”

escalation is

neither the only nor the most likely way this war could expand and get more

deadly. States at war typically escalate not because the other side breaches

some critical threshold or misreads something the other side has done but because

they are losing. That is why Germany adopted unrestricted submarine warfare

in World War I and used V-1 and V-2 rockets in World War II, why Japan began

employing kamikaze attacks in the Pacific War, and why the United States

invaded Cambodia in 1970.

This dynamic is

already at work in Ukraine today. What began as a “special military operation”

expected to last a few days or weeks has become a major war of attrition with

no end. After repeated setbacks, Russia mobilized several hundred thousand more

troops (a step Putin did not expect to take when he started the war). It is now

waging a deliberate campaign against Ukrainian infrastructure. At the same

time, Ukraine’s allies have ramped up their diplomatic, economic, and military

support. There is nothing “accidental” about this process; escalation is

occurring because neither side is ready to negotiate a settlement, and each

side wants to win and certainly not lose.

It is easy to

understand Ukraine’s position: The Ukrainians are fighting for survival. Our

sympathies and material support are with them, and rightly so. But because Americans

are accustomed to blaming the world’s problems on the evil nature of autocratic

leaders, they have more trouble recognizing that Putin and his associates

believe that their vital interests are also at stake. To acknowledge that

reality is not a defense of what Putin has ordered or a justification of what

the Russian military has done to Ukraine; it is simply a reminder that Moscow

didn’t go to war for its amusement and isn’t likely to accept defeat easily.

Unfortunately, this

situation highlights both why ending the war is desirable and why doing so

faces enormous obstacles. If the war goes on, the danger of more dangerous

incidents and the danger of a deliberate decision to escalate will remain

uncomfortably high. Furthermore, we cannot be confident that future incidents

will be properly interpreted or that the temptations to raise the stakes will

always be resisted. Those who have called for greater attention to diplomacy

and more serious efforts to settle are correct in emphasizing the perils that remain

as long as the bullets and missiles are flying.

But negotiations are

no panacea; indeed, it is hard to be optimistic about the prospects of

diplomacy working. Ukraine has considerable momentum on the battlefield, but

there’s no sign that Moscow is ready to compromise, let alone meet all of

Ukraine’s demands. If both sides believe they can improve their situation by

fighting, no deal is possible.

For updates click hompage here