By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

The Reinvention Of China

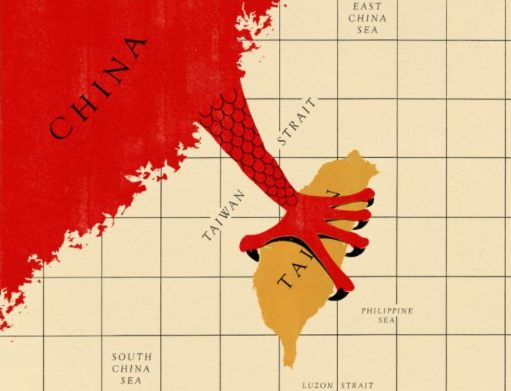

It Is No Secret That China Intends

To Seize Taiwan By 2027

On 10 Dec.

2022, an analyst at the Center for Advanced China Research boldly asked to

suppose the US would defeat a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan. What Then?

Recently,

the Pentagon warned of China’s plans for dominance in Taiwan and beyond.

As part of its buildup, the U.S. says that China’s military conducted more

ballistic missile tests last year than the rest of the world

combined. Chinese fighter jets or drones that intrude into Taiwan’s

territorial airspace will be regarded as a “first strike,” Taiwan’s Defense Minister

warned Wednesday, as the island seeks to step up its

defenses in response to Beijing’s military pressure.

Taiwan has noticed a hole in its defense plans that is

steadily getting bigger. And it’s not easily plugged by boosting the budget or

buying more weapons. The island

democracy of 23.5 million is facing an increasing challenge in recruiting

enough young men to meet its military targets. Its Interior Ministry has

suggested the problem is partly due to its stubbornly low birth rate. Taiwan’s

population fell for the first time in 2020, according to the ministry, which

warned earlier this year that the 2022 military intake would be the lowest in a

decade and that a continued drop in the youth population would pose a “huge

challenge” for the future..

As a reaction to the

above, Japan unveiled a

new national security plan that signals the country’s most significant

military buildup since World War II, doubling defense spending and veering from

its pacifist constitution in the face of growing threats from regional rivals.

But as we have

already observed and frequently analyzed Taiwan for about ten years. Suddenly,

one incident happened during the first quarter of 1919 at the prestigious The

London School Of Economics (LSE), where many heads of state would send their

teenagers and young adults to study there. And while by then, we had already

posted an extensive analysis of how mapmaking developed

in China.

London School of Economics Dilemma

Not too late, 26 March

2019 suddenly became a particularly proud day for the director and staff of the

London School of Economics. A new sculpture by the Turner Prize-winning artist

Mark Wallinger was being unveiled right

outside the recently completed student center. Wallinger’s work

was entitled The World Turned Upside Down, a literal description of the piece.

But one group of

students was unprepared to see the world from a different point of view. Within hours of the unveiling, a few students from the People’s Republic of China

noticed that Taiwan had been colored pink while the PRC had been colored yellow

and that Taipei had been marked with a red square, indicating a national

capital, rather than the black dot used for provincial cities. They protested

to the director and demanded that the work be changed. In their view, the artist’s

intent was irrelevant: Taiwan should be just as yellow as the mainland.

The LSE suddenly was

facing a ‘Gap moment.’ Students from the PRC make up 13 percent of the total

student body at the LSE,1 so a boycott could have been ruinous. At the same time,

the school’s Taiwanese students and their supporters also rallied. They pointed

out that Taiwan’s president, Tsai Ing-wen, was a

graduate of the LSE, a fact that had been trumpeted by the school when she

was elected. Two days later, the artwork had expanded to include a notice

stating, ‘The LSE is committed to . . . ensuring that everyone in our community

is treated with equal dignity and respect.’2

Wallinger avoided media comment except for one interview

with the LSE student newspaper, The Beaver, in which he said, ‘There are a lot

of contested regions in the world; that’s just a fact.’ The arguments continued

for several months until, in July 2019, the LSE and Wallinger made

a minor concession. They added an asterisk next to the name ‘Rep. China

(Taiwan)’ on the work and a sign below it stating, ‘There are many disputed

borders, and the artist has indicated some of these with an asterisk.’3 But

Taiwan remained a different color: the LSE and the artist held their nerve.

They did not ‘do a Gap,’ The sculpture continues to represent political reality

rather than an idealized version of ‘maximum China’ imagined by its

patriots online and offline.

China, until after

the defeat of Chiang

Kai-shek’s KMT, was not interested in Taiwan.

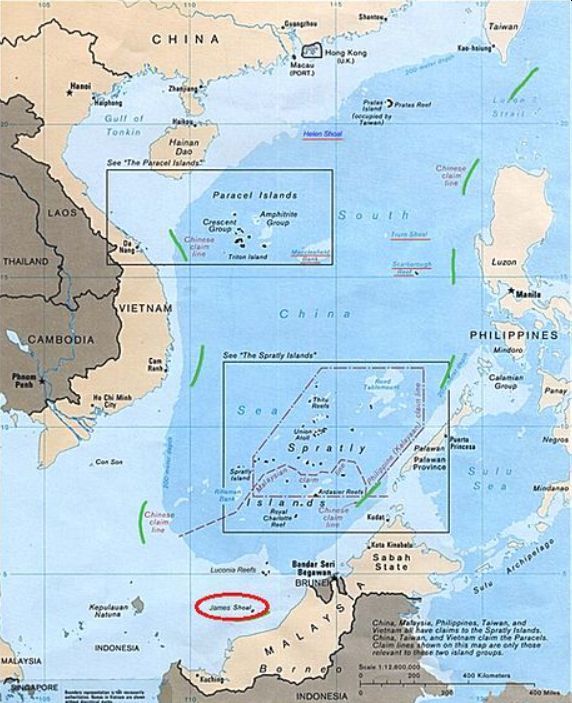

The Non-Existing South China Sea Islands

All evidence shows that the Qing

emperors made no effort to administer Taiwan, so by the time Japan acquired the

island in 1895 after the Sino-Japanese war, the map they first drew defined

that region – about half the island – as unadministered tribal territory. Fifty

years of Japanese rule created the sinews of modern Taiwan, with improved

agriculture, education, railways, and urban development, all having a Japanese

feel that prevails today. Although facing initial resistance, the Japanese

treated Taiwan gently compared to Korea, and a legacy of goodwill remains.

After the Japanese

defeat, the Taiwanese yearned not for independence but autonomy from a chaotic

mainland in the grip of the civil war between Chiang Kai-shek’s KMT government and the Communists.

But such Taiwanese thoughts of independence were brutally suppressed by

February 28, 1947. In the following days, 5,000 to 10,000 Taiwanese, including

many local leaders, were shot by Chiang’s forces, and Taiwan’s identity was

suppressed.

KMT domination was

massively reinforced by Chiang’s retreat to the island in 1949, supposedly as

the base from which to reclaim the mainland. About one million KMT loyalists

fled to Taiwan in 1949, becoming about 15 percent of the population and

controlling all the levers of the state, with martial law continuing until

1987.

That Taiwan

moderately prospered over the following decades was less due to KMT rule than

to the combination of the education and modernization instilled by Japan and by

the capital and markets that the US offered. Refugee capital and expertise from

the mainland also played a role. Growing prosperity and the death of Chiang

Kai-shek gradually saw the emergence of a more liberal state after Taiwanese

Lee Teng-hui became vice-president in 1984 and president in 1988, the decline

of mainlander influence and the rise of the overly pro-Taiwan autonomy

Democratic Progressive Party.

And even if one were

to claim Taiwan may be culturally Chinese, its history is different; its years

under mainland Han rule were relatively brief. The fact that most of its

population is of Han Chinese origin is irrelevant – Singapore is majority Han

Chinese too.

President Xi might believe a large part of the Pacific ('the

South China Sea') in reality belongs to

China, as has been

taught in Chinese schools since the 1940s based on a map

created by cartographer Bai Meichu in 1936, who later advised the Republic of China

government on which territories to claim after the Second World War.

In the

above-mentioned New Atlas of China's Construction (中華建設新 圖), the James Shoal (off Borneo), Vanguard

Bank (off Vietnam), and Seahorse Shoal (off the Philippines) are drawn as

islands. Yet, they are underwater features largely due to mistranslations

using what was

originally a British publication.

As we have earlier

described, a turning point for Bai and others who saw China's need to create a new Nation-State was

the Versailles peace conference's outcome in 1919. In an article in the June 2013 issue of China

National Geography,

Shan Zhiqiang, the chief executive editor,

added: The nine-dashed line has been painted in the hearts and minds of

the Chinese for a long time. It has been 77 years since Bai Meichu put in his 1936 map. It is now profoundly

engraved in the hearts and minds of the Chinese people. There will not be any

time when China will be without the nine-dashed line.

The Making Of The Chinese Pacific

It is clear that Bai

(whose New Atlas of China owed as much to his nationalist imagination as

to geographical reality) was quite unfamiliar with the South China Sea

geography and undertook no survey work of his own. Instead, he copied other

maps and added dozens of errors of his own, which continue to cause problems to

this day. Like the Maps Review Committee, he was completely confused by the

portrayal of shallow water areas on British and foreign maps. Taking his cue

from the names on the committee’s 1934 list, he drew solid lines around these

features and colored them in, visually rendering them on his map as islands

when in reality, they were underwater. He conjured an entire island group

across the sea center and labeled it the Nansha Qundao, the ‘South Sands Archipelago.’ Further south,

parallel with the Philippines coast, he dabbed a few dots on the map and

labeled them the Tuansha Qundao,

the Tuansha Qundao,

the ‘Area of Sand Archipelago.’ However, at its furthest extent, he drew three

islands, outlined in black and colored in pink: Haima Tan

(Sea Horse Shoal), Zengmu Tan (James

Shoal), and Qianwei Tan (Vanguard Bank).

Thus, the underwater

‘shoals’ and ‘banks’ became above-water ‘sandbanks’ in Bai’s imagination. On

the map's physical rendering, he then added innovation of his own: the same

national border that he had drawn around Mongolia, Tibet, and the rest of

‘Chinese’ territory snaked around the South China Sea as far east as the Sea

Horse Shoal, south as James Shoal and as far southwest as Vanguard Bank. Bai’s

meaning was clear: the bright red line marked his ‘scientific’ understanding of

China’s rightful claims. This was the first time such a line had been drawn on a Chinese map.

A key part of the

assertions was to make the names

of the features in the sea sound more Chinese. In October 1947,

the RoC Ministry of the Interior issued a

new list of island names. New, grand-sounding titles replaced most of the 1935

translations and transliterations. For example, the Chinese word for Spratly

Island was changed from Si-ba-la-tuo to Nanwei (Noble South), and Scarborough Shoal was

changed from Si-ka-ba-luo (the

transliteration) to Minzhu jiao (Democracy Reef). Vanguard Bank’s Chinese name

was changed from Qianwei tan to Wan’an tan (Ten Thousand Peace Bank). Luconia Shoals' name was shortened from Lu-kang-ni-ya to just Kang, which

means ‘health.’ This process was repeated across the archipelagos, largely

concealing the foreign origins of most of the names. A few did survive,

however. In the Paracels, ‘Money Island’ kept

its Chinese name of Jinyin Dao and Antelope

Reef remained Lingyang Jiao. To this day,

the two names celebrate a manager and a ship of the East India Company,

respectively.

At this point, the

ministry seems to have recognized its earlier problem with the translations of

‘shoal’ and ‘bank.’ In contrast, in the past, it had used the Chinese word tan

to stand in for both (with unintended geopolitical consequences); in 1947, it

coined a new word, ansha (Ànshā), literally ‘hidden sand,’ as a replacement. This

neologism was appended to several submerged features, including James Shoal,

renamed Zengmu Ansha.

In December 1947, the

‘Bureau of Measurements’ of the Ministry of Defence printed

an official ‘Location Map of the South China Sea Islands, almost identical to

the ‘Sketch Map’ that Zheng Ziyue had drawn

a year and a half before. It included the ‘U-shaped line’ made up of eleven

dashes encircling the area down to the James Shoal. In February 1948, that map

was published as part of the Atlas of Administrative Areas of the Republic of

China. The U-shaped line, with an implicit claim to every feature within it,

became the official position.

Therefore, it was in

1948 that the Chinese state formally extended its territorial claim in the

South China Sea to the Spratly Islands, as far south as James Shoal. Something

changed between July 1933, when the Republic of China government was unaware

that the Spratly Islands existed, and April 1947, when it could ‘reaffirm’ that

its territory's southernmost point was James Shoal. What seems to have happened

is that, in the chaos of the 1930s and the Second World War, a new memory came

to be formed in officials' minds about what had happened in the 1930s. It seems

that officials and geographers managed to confuse the real protest issued by

the RoC government against French

activities in the Paracels in 1932 with a

non-existent protest against French actions in the Spratlys in

1933. Further confusion was caused by the intervention of Admiral

Li Zhun and his assertion that the islands annexed by France in 1933

were indisputably Chinese.

The imagined claim

conjured up by the confusion between different island groups in that crisis

became the real territorial claim.

Pratas's islands are now a conservation zone where

visitors can send postcards back home from a mailbox guarded by a

cheerful-looking plastic shark. Not far away is a new science exhibition

explaining the natural history of the coral reef and its rich marine life.

Overlooking the parade

ground (which doubles as a rainwater trap) stands a golden statue of Chiang

Kai-shek in his sun hat, and behind him is a little museum in what looks like a

scaled-up child’s sandcastle.

This museum holds, in effect, the key to resolving the

South China Sea disputes. Its assertion of Chinese claims to the islets

demonstrates the difference between nationalist cartography and actual

administration. Bai Meichu may have drawn a

red line around various non-existent islands in 1936 and claimed them as

Chinese, but no Chinese official had ever visited those places. The maps and

documents on the museum walls tell the Republic of China (RoC) expedition's story to Itu Aba

in December 1946 and a confrontation with some Philippine adventurers

in 1956. Still, without any other evidence, the museum demonstrates that China

never occupied or controlled all islands. In the Paracels,

it occupied one, or just a few, until 1974, when the People’s Republic of China

(PRC) forces invaded and expelled the Vietnamese garrison. In the Spratlys, the RoC occupied

just one or two. The PRC took control of six reefs in 1988 and another in 1994.

The Current Reality

For the people of Taiwan,

joining the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has never been less appealing.

According to a frequently cited tracking survey by National Chengchi

University, the share of Taiwanese residents who want to unify immediately with

the mainland has always been minuscule, consistently less than three percent.

But the percentage that thinks Taiwan should eventually move toward

unification—not necessarily with today’s Chinese regime—has fallen

dramatically, from 20 percent in 1996 to five percent today. In the last two

presidential elections, the historically pro-unification Kuomintang party (KMT)

has suffered landslide defeats, failing to garner even 40 percent of the vote.

President Tsai

Ing-wen stepped down

as party chairperson at

the DPP’s post-election press conference, accepting responsibility for the

party’s poor performance. On the same stage, in almost the exact words, Tsai

resigned from the same position only four years ago, following the devastating

2018 local elections, during which the DPP lost seven of

the 13 seats it

held.

In a column penned in 2018, You Ying-lung, the chairman of the Taiwan Public

Opinion Foundation (TPOF), wrote that the DPP had lost two years into the Tsai

administration mainly for failing to reflect public opinion.

In 2022, with only

six offices left to defend, the DPP still dropped one seat — for a similar

reason. During local news channel TVBS’s live election night coverage, TPOF Chairman You said, “there are wide

discrepancies between the DPP’s grasp of public opinion and the party’s

direction,” failing many of its strategies and candidates in this election

cycle.

Even Though China Will Be Planning An Invasion, Taiwan

Has Its History, Culture, Identity, And National Pride.

It is easy to understand

why unification is so unpopular. Over the last four decades, Taiwan has transformed itself into a liberal, tolerant,

pluralist democracy. China has remained a harsh autocracy, developed an

intrusive surveillance state, and executed genocide against its population.

Unifying with the PRC would mean the end of almost all of Taiwan’s hard-won

political freedoms, manifesting when China forcibly integrated Hong Kong into

the mainland despite its promise to allow the territory to remain

self-governing under a formula called “one country, two systems.” And many, or

perhaps most, Taiwanese people would not want to unify with China regardless of

the nature of its government. Taiwan has its history, culture, identity, and

national pride.

Yet, although public

opinion data make it clear that the overwhelming majority of Taiwanese people

have little interest in being ruled by Beijing, that does not mean they want a

formal declaration of independence. The country’s understanding of independence

has evolved significantly over the last generation among the general public and

political elites. In decades past, independence was commonly thought to require

an unequivocal, formal break with any legal or professed ties to China. But

today, such a move is widely seen as unnecessary. To most people, Taiwan is

already a fully sovereign country, not merely a self-governing island that

exists in a state of limbo. There is no need to rock the boat by formally

declaring what is already the case, especially given that Beijing would

undoubtedly have a furious response to such an action. And since Taiwanese

politicians must respond to public opinion, political elites who support

independence have primarily come to the same conclusion as the country’s

people; rather than quixotically challenging the status quo, most of them have

decided that any differences between their ideal position and the status quo

are minor—and not worth fighting over.

It surprises many

Westerners to learn that Taiwanese independence is not merely rooted in

anti-Chinese sentiments and that it is not an idea that arose only after 1949

when Republic of China (ROC) leader Chiang Kai-shek and his million and a half

followers fled to the island after losing the Chinese Civil War. The year 1895,

when Beijing ceded Taiwan to Japan after being defeated by Tokyo in a war, was

arguably just as pivotal as 1949. A modern sense of Taiwanese national identity

began to take shape, and there were calls for Taiwanese autonomy and

independence throughout the Japanese colonial era. Taiwan independence activist

Su Beng pushes the timeline

back even further, arguing in his seminal 1962 work, Taiwan’s 400-Year

History, that Taiwan has been a distinct nation and society since

large-scale Han immigration to the island began in the early 1600s. For Su, Taiwan’s history was marked by repeated colonization

and exploitation by external powers as the Dutch, Spanish, claimants to the

throne of the disintegrating Ming dynasty, the Qing dynasty, the Japanese, and

Chiang’s Kuomintang (KMT) all set up regimes in Taiwan for their

purposes—denying the Taiwanese people control over their destiny.

Chiang’s regime in

Taiwan rested on the idea that the ROC had not lost the civil war and was still

China's legitimate government. Although the ROC positioned itself as a

democracy, the KMT could not risk any open challenges to this claim, so it

declared martial law. National-level representatives were frozen in office

without the need to face reelection, and the government systematically silenced

political opposition. The KMT kept a firm grip on the country’s entire

political edifice through its control of the state machinery, especially the

military. Any Taiwan-centric appeals, especially for Taiwanese independence,

were seen as a direct affront to the regime’s legitimacy and were ruthlessly

suppressed. Throughout the KMT authoritarian era, the ROC government was the

primary obstacle to Taiwanese political power and self-rule.

As a result,

Taiwanese nationalists concluded that the way to set the Taiwanese people free

was to slough off this entire political structure. The KMT, the ROC, and any

ties to China had to go. But as Taiwan democratized in the late 1980s and early

1990s, these activists discovered that their vision had limited appeal. In

1991, the country’s geriatric officeholders were finally compelled to retire.

Taiwan was able to fully reflect a national-level representative body for the

first time as every seat was at stake in the National Assembly, an institution

with the power to elect the president and amend the constitution. (The body was

later abolished.) The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP)—the KMT’s main

opposition—confidently called for replacing the Republic of China with a

formally independent Republic of Taiwan. It was a disaster; the DPP won 23

percent of the vote. The electorate's verdict was that formal independence was

just too radical, and for a generation afterward, the country’s common

political wisdom was that Taiwan's independence was ballot-box poison.

At the time, it still

seemed possible that Taiwan would eventually unify with the mainland. For

decades, the authoritarian regime had taught the population that unification

was desirable and inevitable. Taiwan’s gradual democratization did not feature

a sharp break from the past, so the KMT remained in power even after people

could vote. Pro-unification Chinese nationalists retained outsize cultural and

political influence. Meanwhile, China was experiencing the rapid economic

growth that Taiwan had undergone decades ago—the growth that had helped Taiwan

democratize. Many Taiwanese people believed the mainland would surely

experience similar political reforms as its economy kept expanding. Chinese

nationalists in Taiwan expected that once China changed and the two states

rejoined, Taiwan would play an influential (and perhaps predominant) role in

shaping their shared future. Unofficial bodies from the two sides even met in

1992 and 1993, taking the first steps toward establishing regular communication

channels. The question of sovereignty illustrated both hopes for pragmatic

cooperation and how difficult compromise would be. Since hammering out a

mutually acceptable written statement was impossible, the delegates informally

agreed to talk past each other in what would later be (ironically) dubbed the

1992 Consensus. Each side orally stated its version of the “one China” principle,

pretended not to hear the other side, and refused to acknowledge that there

could be any different interpretation.

But the hopes that

the two sides would gradually become more similar and inch toward a mutually

agreeable political union were misplaced. As Taiwan’s democracy deepened,

appeals to Chinese nationalism found a smaller and smaller receptive audience

among the island’s population. At the same time, the PRC became more rigid and

domineering instead of democratizing as it grew wealthier and more

powerful.

The arc of the 1992

Consensus encapsulates these failed hopes. After losing the 2000 presidential

election to the DPP, KMT chair Lien Chan rebuilt his party on a vision of

making Taiwan rich and ensuring peace by integrating Taiwan’s economy into

China’s. To guarantee that PRC officials would be willing to engage with their

Taiwanese counterparts, Lien devised a formula based on what the two sides had

supposedly agreed to in 1992: “One China, each side with its interpretation.”

Ordinary Taiwanese voters were reassured that the status quo would be preserved

since Taiwan’s interpretation was that “one China” meant the ROC. This formula

laid the foundation for KMT politician Ma Ying-jeou’s

presidency, which featured a great deal of official contact with China and

economic interaction. But the PRC became increasingly insistent that the 1992

Consensus was simply that there was “one China”—the PRC—and demanded concrete

progress toward unification. It never acknowledged the “each side with its own

interpretation” part of the equation, so confederation would mean that the ROC

ceased to exist. This not only choked the consensus to death by depriving it of

any ambiguity or flexibility, but it also made clear that the KMT and ROC were

not equal—or even unequal—partners with the Chinese Communist Party and the PRC

in determining China’s future. The KMT’s dreams of creating a peaceful,

prosperous, democratic, unified China were utterly discredited, and the

incompatibility of the PRC’s position with the preservation of the ROC made

unification the new ballot-box poison.

As It Is

Since its 1991

election debacle, the DPP has steadily moved away from a formal independence

platform. By 2000, it took the position that Taiwan was already an independent,

sovereign state named the Republic of China, and no declaration of independence

was necessary. Current Taiwanese President China Tsai Ing-wen, a DPP

politician, has developed the idea of Taiwanese sovereignty more fully:

eschewing formal autonomy is not the only way she differs from earlier

independence activists. Tsai emphasizes the Taiwanese people’s unique, shared

history, including the “white terror” (the violent repression carried out by

the KMT’s autocracy), military standoffs with Beijing, rapid economic growth,

democratization, sporting triumphs, and natural disasters. However, her vision

of the Taiwanese people is constructed on 70 years, not 400 years, of common

experience, so it explicitly includes postwar immigrants as integral parts of

the population rather than as colonizing outsiders. She has even positioned

herself as a champion of the military, recasting an institution that was once

the bedrock of the authoritarian regime and the archenemy of Taiwanese

nationalism as the guarantor of Taiwan’s integrity and sovereignty.

Tsai’s ideas do not

make traditional independence activists happy; many hardcore DPP supporters

dream of an independence referendum and feel slightly queasy when she poses

with a ROC flag. But hers is a position that fits quite comfortably with what

most Taiwanese people want. The National Chengchi

University tracking poll on public attitudes toward unification and

independence shows that, although support for independence has risen over time,

most Taiwanese people prefer the status quo. Other polls suggest that the

tracking surveys might underestimate the depth of support for the status quo.

Two postelection surveys, one from 1996 and one from 2020, asked people who

preferred the status quo whether they would support unification if political,

economic, and social conditions in China and Taiwan were similar (for instance,

if China became a wealthy democracy), or if they would support declaring

independence if doing so wouldn’t provoke retaliation from Beijing. The share

of status quo supporters open to unification, even under these ideal

hypothetical conditions, plummeted from 58 to 22 percent. The share of status

quo supporters open to independence remained roughly stable, drifting from 57

to 54 percent.

It is clear from the

main tracking poll and the responses of status quo supporters that fewer people

today want unification. But as for the growing support for independence, it is

critical to remember that ideas about the meaning of independence have changed.

A 2020 study found that more than 70 percent of Taiwanese people believe their

country is already a sovereign state and that only a tiny fraction felt a need

to sever ties with China formally. The increased support for independence over

the past few decades does not necessarily indicate that a growing number of

citizens are clamoring for a declaration of independence.

This shift in opinion

has only sometimes resulted in electoral success for the DPP. During the last

two local elections, the party has performed disastrously. On November 26, Tsai

was compelled to step down as party chair after the DPP could only win five of

22 mayoral races. But it would be a mistake to interpret these results as a

shift in public attitudes toward unification or away from independence. The

local elections were about local government issues such as road construction,

welfare programs, and responses to the pandemic—not China. Most races are best

understood as referendums on the performance of popular KMT incumbents running

for reelection. Notably, sovereignty or how to deal with China has been mainly absent from the DPP’s

post-election discussions about the reasons for the poor outcome. Likewise, no

one in the KMT is crowing that this result means it no longer has to worry

about being attacked as a pro-unification party.

But although Tsai may

no longer be the party chair, her grand vision for Taiwan’s future—situating

Taiwan in the international community of democracies, strengthening the

country’s military and bolstering cooperation with other armies, gradually

diversifying Taiwan’s economy, pursuing progressive social welfare policies,

defending Taiwan’s sovereignty, and a host of other measures—remains unchallenged

inside the DPP. China will inevitably be on the ballot in the 2024 presidential

and legislative elections. Unless the DPP forfeits its dominant position as the

champion of the status quo by recklessly pursuing formal independence, it

should once again have a clear electoral advantage.

As aptly

written, If Washington is to escape a cycle of conflict or the constant threat

of conflict with China over Taiwan, it will require bolder policymaking than

efforts to smooth over differences with Beijing in the aftermath of a war.

Defeating an invasion force alone will not be enough to win Taiwan's peace.

Given the difficulties inherent in either conventional or nuclear deterrence,

even following a major victory, before Washington undertakes what may be merely

the first of several phases of a Taiwan conflict, it should consider whether it

is willing to run the risks required to win the peace that is to follow.

In the end, as Connor

Swank aptly wrote

in The Diplomat, If Washington is to escape a cycle of conflict or the

constant threat of conflict with China over Taiwan, it will require bolder

policymaking than efforts to smooth over differences with Beijing in the

aftermath of a war. Defeating an invasion force alone will not be enough to win

Taiwan's peace. Given the difficulties inherent in either conventional or

nuclear deterrence, even following a major victory, before Washington

undertakes what may be merely the first of several phases of a Taiwan conflict,

it should consider whether it is willing to run the risks required to win the

peace that is to follow.

1. LSE Undergraduate

and Postgraduate Students Headcount: 2013/14–2017/18, https://info.lse.ac.uk/staff/divisions/Planning-Division/Assets/Documents

.

2. CNA, ‘Lúndūn zhèng jīng

xuéyuàn gōnggòng yìshù jiāng bǎ

táiwān huà wéi zhōngguó wàijiāo

bù kàngyì’, 7 April 2019,

https://www.cna.com.tw/news/firstnews/201904040021.aspx (accessed 2 March

2020).

3. Keoni Everington, ‘LSE ignores

Chinese cries, add an asterisk next to Taiwan on the globe,’ Taiwan News, 10

July 2019, https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/en/news/3742226 (accessed 2 March

2020).

4. Keoni Everington, ‘LSE ignores

Chinese cries, adds asterisk next to Taiwan on the globe’, Taiwan News, 10 July

2019, https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/en/news/3742226 (accessed 2 March 2020).

For updates click hompage here